…I’ll tell you what my film is about: it’s about the naked alienation of the inner self against the outer self – alienation taken to the extreme…

…It’s about identity – about everybody’s identity – so we superimpose our own vision on Renaldo: it’s his vision and it’s his dream…

Bob Dylan, extracts from interview in Rolling Stone with Jonathan Cott, 1978

…I don’t have a clue what the Rolling Thunder tour was about… It’s about nothing… It happened so long ago I wasn’t even born…

Bob Dylan, interview in The Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story, 2019

…I want to be buried in an unmarked grave…

Bob Dylan (as ‘Renaldo’) in Renaldo and Clara, 1978

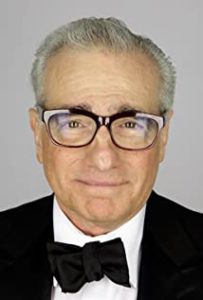

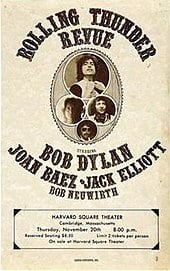

The two films about Bob Dylan’s Rolling Thunder tour, made over forty years apart, received immensely different critical receptions. The Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story, made for and shown on Netflix rather than in cinemas directed by leading Hollywood auteur Martin Scorsese, was almost universally acclaimed. Owen Glieberman in Variety called it an …audaciously alive 2-hour-and-22-minute Scorsese feast of a 1970s verité sprawl…. Ian Freer in Empire acclaimed it as …a multi-faceted portrait of a creative artist, a prescient portrait of ’70s America in crisis, and a meditation on the nature of documentary itself… In contrast, Renaldo and Clara, directed by Dylan himself and released in 1978, was so slated by critics that it was withdrawn from theatrical exhibition after just a few showings. Despite the obvious commercial potential of any film featuring Bob Dylan, it has, as yet, never been released on video tape, DVD or on a streaming service. In what can only be called a vicious diatribe, the famed American film critic Pauline Kael wrote that the film ...is marked by an absence of artistic intelligence. The picture hasn’t been thought out in terms of movement or a visual plan… It was widely condemned as a self-indulgent ‘vanity project’.

Today the Rolling Thunder tour has quite rightly attained a legendary status as one of the high points – if not the high point – of Bob Dylan’s performing career. Scorsese’s witty and cleverly constructed film has certainly enhanced the reputation of the tour. As with No Direction Home, his lengthy and carefully structured film about Bob Dylan’s origins and his iconoclastic move into rock music in the 1960s, the director worked mostly with existing stock footage. Both films are what might be called quasi-documentaries. Scorsese mixes this material with contemporary interviews, assembling the material not in a chronological way but in order to tell a story cinematically. He has the advantage that the material he is working with includes some truly marvellous performances. Yet the two films tell their stories very differently. The narrative of No Direction Home follows the outline of what might be called a pre-existing drama. Dylan wows the world with his protest songs, becomes a folk hero. Then he ‘goes electric’ and rejects political song writing in favour of surreal poetic explorations of consciousness and the imagination. The fans – or certainly a vocal minority of them – react with horror. They turn up at the shows and boo Dylan’s electric sets, culminating in the now legendary cry of “Judas!” at the Manchester Free Trade Hall in May 1966. Scorsese merely has to rearrange his material to fit this. But the Rolling Thunder tour presents him with a different problem, in that – whatever its aesthetic merits – it did not change the world in such a dramatic way. There was no conflict with the audiences, no obvious dramatic denouement.

MARTIN SCORSESE

Scorsese’s first attempt at the film consisted of him assembling the material to tell the story of the planning and execution of the tour. But what he ended up with seemed to him to be rather mundane and uncinematic. So he began to add a number of fictional elements. Thus Rolling Thunder Revue is a very different film to No Direction Home. Scorsese clearly decided to make the film basically a comedy. In doing so he had the advantage that Dylan’s own performance in his interview clips displays much of his latter day coolly self deprecatory ‘interview persona’ in which any statement he makes seems deliberately weighted with heavy comic irony. At several points Dylan even plays along with Scorcese’s inventions, although there are moments when he seems about to burst into laughter. There are also extracts from contemporary interviews with Joan Baez, Ronnie Hawkins, ‘Hurricane’ Carter and band members Steven Soles and Scarlet Rivera; while Allen Ginsberg (who died in 1997) is featured talking about the tour. These clips give the film documentary credibility. But Scorsese toys with its audience in a self-referential and knowing way, somewhat in the manner of Dylan’s late period ‘tongue in cheek’ songs like Highlands, Things Have Changed, Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum or Goodbye Jimmy Reed. It might be possible for viewers with no knowledge of Dylan’s history at all to be fooled by Scorsese’s inventions, but the majority of the audience surely began to ‘smell a rat’ when some of the contemporary interviewees were introduced.

Perhaps the most glaringly obvious of these is the Hollywood star Sharon Stone, who claims to have been on the tour as a nineteen year old after having claimed Dylan’s autograph. This is supported by a faked black and white photograph showing her as a teenager as Dylan signs for her. She even hints that they had an affair, asserting that Dylan played Just Like a Woman to her, telling her he had written it for her. She relates having discovered that this was not true (It had, of course, been written for Blonde on Blonde ten years previously) and gives us a little patented Hollywood sniffle, suggesting that Dylan acted like a cad. Stone’s performance is something of a ‘give away’ in that her reaction to Dylan’s supposed behaviour is deliberately overplayed. Scorsese must have known that eager Dylanologists would soon spot all the flaws. Sharon Stone was born in 1958 so would have been only 17 when the first Rolling Thunder gigs were played. The ‘autograph’ picture had of course been ‘Photoshopped’. But perceptive viewers’ suspicions would surely have been raised already. Another ‘real life’ character is Jim Gianapulos, the CEO of Paramount Pictures, who claims he was the promoter of the Rolling Thunder Revue, who tells us what a financial disaster the tour was.

Other interviewees are, however, completely fictional. The actor Michael Murphy appears as the politician ‘Jack Tanner’, a character from the miniseries Tanner 88. He claims that he attended one of the shows at the request of Jimmy Carter, who would be elected president in 1976. This is something of an ‘in joke’ as Carter professed to be a Bob Dylan fan and later even invited Dylan to visit the White House. Tanner 88 (1988) is a ‘mockumentary’ directed by Robert Altman. By including Murphy, Scorsese is again playing games with the audience, only a few of whom are likely to remember his role in this relatively obscure series from thirty years ago. More problematical is the inclusion of Stefan van Dorp (Martin von Haselberg) who – we are told – shot all the contemporary footage that is used in the movie. Van Dorp, who is a very unpleasant character, makes several appearances. At one point he claims that he only agreed to be interviewed in order to stake a financial claim in regard to the footage. He states that the film he intended to make would have shown …the contrast between the excesses of the people on the tour and the dissolution of society [in] the land of pet rocks and Slurpees from 7-Eleven… The inclusion of these characters deliberately blurs the line between fiction and reality, just as Renaldo and Clara does, but in aiming for a comic effect, Scorsese rather misses the mark. If the fictional characters had been a little more ’larger than life’ their inclusion might have contributed to making the film a more appealing comic fantasia. But the character of the arrogant and egotistical Van Dorp in particular is merely annoying and extremely unconvincing, especially when he claims that LSD was his ‘drug of choice’. Psychedelic he is decidedly not…

Scorsese’s attempts to place the film in a historical-political context are also rather unsuccessful. The opening sequences place much emphasis on state of the US in the immediate post-Watergate, post-Nixon era. Dylan himself comments that things were so crazy then that …two people tried to kill the president in a week… Much focus is placed on the fact that the tour more or less coincided with the Bicentennial Celebrations of 1976. Scorsese shows footage of marching bands and characters dressed in US flags. In fact, the first half of the tour, from which all the footage is drawn, took place in late 1975 rather than in the centennial year itself. Although the ‘revised’ version of Dylan’s Idiot Wind from Blood on the Tracks, released a year earlier, included the immortal line …Idiot wind, blowin’ like a circle around my skull/ From the Grand Coulee Dam to the Capitol… in fact the Rolling Thunder Revue, and its attendant album Desire (released in early 1976), had little explicit political content of any kind. The director’s visual and narrative ‘tricks’ are cleverly executed and help the film hold together as a challenging ‘mockumentary’. Considerable emphasis is placed on the way films can create an illusion of reality. This is spelled out to us pretty clearly in the film’s opening homage to the original cinematic ‘trickster’ Georges Melies, whose ‘special effects’ films such as 1901’s Voyage to the Moon were among the most important and innovative early cinematic innovations. Scorsese had previously paid tribute to Melies in his film Hugo, set in fin-de-siècle Paris. Thus the director superimposes a convincing narrative shape onto the film and turns out an entertaining couple of hours. But his film is in many ways a reconstruction of the supposedly ‘disastrous’ Renaldo and Clara, around which the entire concept of the Rolling Thunder Revue was created, and for which the contemporary footage that Scorsese uses was filmed. Dylan’s movie is far less conventional that Scorsese’s and far less ’professional’ in terms of acting, editing and pacing. But it is more serious, adventurous and profound. Like 2002’s Masked and Anonymous, for which Dylan co-wrote the script and played the lead role – it is a ‘poetic’ film which ignores conventional cinematic structures and conventions and which plays far more radical and challenging ‘games’ with its audience than Scorsese’s effort. In the fullness of time, the Scorsese film will always be in Renaldo’s shadow.

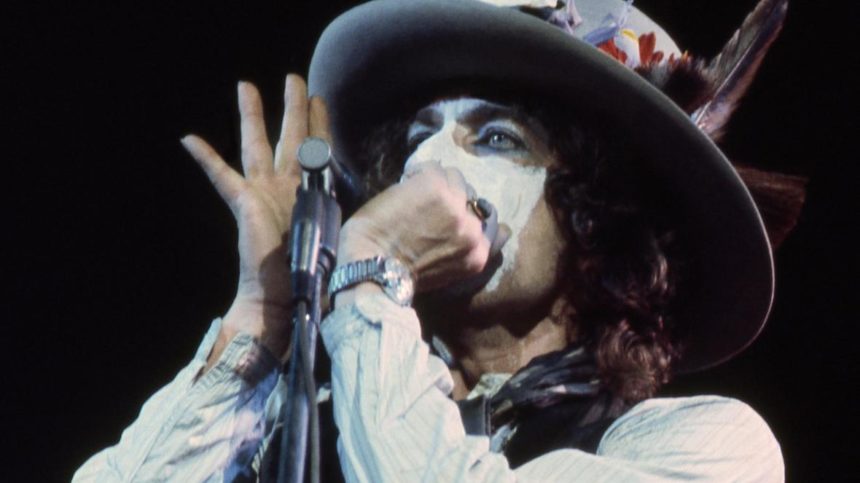

There is no doubt that The Rolling Thunder Tour: A Bob Dylan Story is an immensely enjoyable two hours, which Dylan fans will certainly watch over and over. But its secrets will, by the end of a second viewing, have revealed themselves. In the case of Renaldo and Clara, only through repeated viewings do its real themes emerge. Like Dylan’s greatest songs, it can never be tied down to any specific meaning. And its ‘dramatised’ sequences relate directly to Dylan’s songs in a way that Scorsese’s additions never really attempt to do. In many ways, Scorsese’s film is a missed opportunity. By far its greatest asset, apart from the rather cryptically comic persona that Dylan adopts in his interview segments, is the footage of the Rolling Thunder shows which were filmed during the tour by Dylan’s co-editor and cinematographer Howard Alk. Alk was an independent film maker and friend of Dylan’s who died young in 1982. He and Dylan had previously worked together on Eat the Document, a record of the epochal 1966 ‘Judas’ tour with The Band (then The Hawks) which was made for TV but was considered far too ‘weird’ to be shown on the ‘family friendly’ network TV of the US in the late 60s. Like Renaldo, Eat the Document uses a ‘cut up’ narrative, with disconcerting jump cuts and other editing techniques, many of which were derived from early 1960s French ‘Nouvelle Vague’ cinema; especially films like Jean Luc Godard’s Breathless and Francois Truffaut’s Shoot the Piano Player where conventional narrative techniques were sidestepped or satirised. Alk’s work in filming the onstage sequences that appear in Renaldo and Clara outstanding. We see the whole band in action many times, as they lurch chaotically around the stage with Mick Ronson (recently released from Bowie’s Spiders from Mars) on lead guitar. But the most effective shots are the lingering close ups of Dylan himself, his white face make up shaded by his cowboy hat decorated with flowers. Dylan himself is deliberately playing to the camera, quite aware that his performances will end up in his own film. Scorsese could have used the footage to create a great concert film, just as he did with 1978’s The Last Waltz. Given that most of Alk’s footage is still unused, maybe somebody will do it one day.

The magnificent live performances of Dylan and other members of his entourage illuminate both films. The songs are all highly rearranged from their original recorded forms. The selections from Desire – which had been recorded but not yet released – are developed into intense performance pieces. The close ups allow us to see how Dylan is acting out the songs in his own mind. On Isis he sings without a guitar, illustrating the song with his body movements, just as he was to do much later in his ‘crooning’ phase of the mid-2010s. He puts his heart, body and soul into every performance. His timing, and his phrasing of the lyrics, are impeccable. The ragged band, all of them clearly high on adrenaline (and God knows what else), respond to his leadership like no musicians before or since. Though nothing like as technically proficient as The Band, Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, The Grateful Dead or Dylan’s many Never Ending Tour Bands, the entourage show they can match the incredible manic intensity and vital spontaneity of Dylan’s performances. Dylan himself has sometimes been described as a modern shaman, a weaver of magic who casts a spell on the audience. At no other time in his career does he justify this description more accurately than in these performances. In Renaldo we see full and uninterrupted versions of a highly energised and ‘electrified’ A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall, as well as The Water is Wide, Tangled Up in Blue, One More Cup of Coffee, Sara and It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train To Cry. In these performances – perhaps the greatest of Dylan’s entire career – his improvisational aesthetic reaches a peak. His band features four, sometimes five, ‘lead guitarists’ creating a ‘wall of sound’ behind him in renditions that are never the same from one night to another.

Both films feature versions of Isis, arguably the centrepiece of Desire. The songs on Desire (mostly written in collaboration with Canadian theatre director and lyricist Jacques Levy) were specifically composed to be performed on the tour. Almost all of the songs themselves can be called ‘cinematic’. They are structured as a series of ‘scenes’ and lend themselves to dramatic recitation (a theme which will be taken up in more detail in a later blog). By the time the Rolling Thunder Revue reached Montreal on 4th December, Isis had become a stunning theatrical tour de force, far sharper and more dynamic than the recorded version. Dylan’s film presents this performance in stunning close ups. Scorsese uses the version recorded at Boston on 21st November, which includes more long shots but is equally impressive. This is one of the few complete performances included in Scorcese’s film, which begins with a riveting solo Mr. Tambourine Man which Scorsese chooses to intercut with scenes related to the bicentennial and the Watergate scandal. Richard Nixon is shown giving a sanctimonious speech concluding in the declaration that America …acts not just for ourselves but for all mankind…. while Dylan, in the first interview segment, comments on contemporary discussions about the repercussions of the US …being chased out of Saigon… But the juxtaposition of the song with these extracts is of limited value. Mr. Tambourine Man is a celebration of the power of music to achieve spiritual transcendence. It is certainly an appropriate choice to begin a movie about the freewheeling musical approach of the Revue. Scorsese seems to suggest that Dylan’s motivation in starting the tour was somehow to ‘heal the nation’. Here again his apparent lack of understanding of the real substance of Dylan’s songs is demonstrated. Isis is one of the few Dylan performances he shows in full.

DYLAN LINKS

DAILY DYLAN NEWS at the wonderful EXPECTING RAIN

THE BOB DYLAN PROJECT- COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

Leave a Reply