It is a commonplace that Bob Dylan made possible the emergence of a whole generation of singer-songwriters. It is not surprising, therefore, that a number of them have chosen to pay ‘tribute’ to him in song. Not all of the references to Dylan have been complimentary, however. Writing a song about the greatness of another songwriter is not an easy task. Most of these songwriters merely use the figure of Dylan to explore their own concerns. Some are simply in awe of the great man. Cat Power’s Song to Bobby begins by expressing her devotion to him as a teenager and goes on to express her amazement at getting a phone call from his management asking her to support him on tour. Other songwriters merely name drop Dylan (or use an alias for him) to make a specific point. In his devastatingly personal God from his ‘primal scream’ album John Lennon/ Plastic Ono Band (1970), John Lennon recites a litany of heroes, gods and gurus in which he claims he no longer believes. The name ‘Zimmerman’ (which, by now, pretty much everybody knows is Bob’s ‘real’ name) is given pride of place as the penultimate name in the list, after ‘Elvis’ and just before… (gasp!) Beatles. Don McLean’s famous ‘potted history of rock and roll’ American Pie (1971) contains the line …and the Jester sang for the King and Queen, in a coat he borrowed from James Dean… Dylan, of course, is ‘The Jester’. In The Seeker, one of The Who’s most eloquent and forceful singles, Pete Townshend laments that Dylan – along with The Beatles, Timothy Leary and others – has failed to provide answers to the spiritual questions he has been asking. Jeff Tweedy of Wilco, in a song about his own ageing, worries that he has now grown ‘Bob Dylan’s Beard’. Belle and Sebastian’s Like Dylan in the Movies justify the reference by telling the girl to ‘Don’t Look Back’. Marc Bolan (who was so into Dylan that his adopted surname is a contraction of that of his hero) mentions Dylan or refers to him obliquely in a number of his songs, such as Ballrooms of Mars (1973), one of his characteristically fey poetic fantasies. He is more cryptic in his rather splendidly tongue in cheek hit single Telegram Sam, which includes the line …Bobby’s all right, Bobby’s all right/ He’s a natural born poet, he’s just outa sight… It’s also possible that Marc also modelled his trademark ‘corkscrew hair’ on Dylan circa Blonde on Blonde…

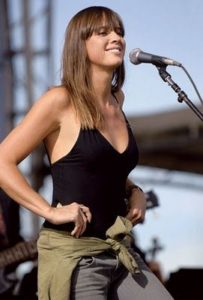

CAT POWER

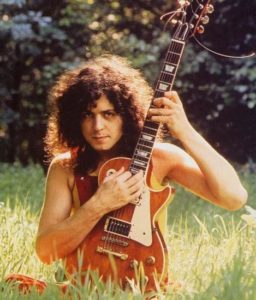

MARC BOLAN

Other songwriters have attempted to parody Dylan or even (shock, horror!) impersonate him. Joan Baez usually insists (apparently for her own amusement) on throwing a few lines of her ‘Dylan voice’ into her stage shows. In her recorded version of Simple Twist of Fate (1975) she even sings a whole verse in a cod-Dylan voice. Paul Simon’s A Simple Desultory Philippic (1966) also attempts to ‘impersonate’ Dylan for comic effect. Satire has never, of course, been Paul’s strongest suit. To be fair, though, his attempt to parody the then-current folk rock boom has a few funny moments, the best of which occurs at the end of the song with his plaintive cry of …I’ve lost my harmonica Albert… a jokey reference to Dylan’s then-manager Albert Grossman. Loudon Wainwright III, whose career increasingly morphed into self-parodic comedy over the years, produced an intermittently funny Dylan-Guthrie ‘taking blues’ parody Talkin’ New Bob Dylan Blues in which he also mentions Bruce Springsteen and John Prine, who along with him were once hyped as ‘new Bob Dylans’. A rather more charmingly unpretentious effort is Syd Barrett’s typically whimsical ditty Bob Dylan Blues, an early Pink Floyd outtake, a in which Syd declares …Gonna write me a song ‘bout what’s right and what’s wrong/ Bout God and my God and all that/ Gonna make like a cat…

SIMON AND GARFUNKEL

A few artists, especially those of the ‘anarcho-punk’ persuasion, have attempted to be rather more scathing. Chumbawamba’s Give the Anarchist a Cigarette, which takes its title from a sarcastic line delivered by Albert Grossman in Don’t Look Back, refers to Dylan as a ‘spoilt brat’ and ends with much repetition of the inscrutable lines: …

Nothing ever burns down by itself/ Every fire needs a little bit of help… The Minutemen’s rather ‘minimalistic’, Bob Dylan Wrote Propaganda Songs does little but repeat the title line. In general, though, Dylan was respected by the punk/new wave generation. Arguably the seeds of punk itself (not to mention rap) are contained in Dylan’s own torrent of street-jive Subterranean Homesick Blues. The greatest singer-poet of the New Wave, Elvis Costello, is a confirmed Dylan acolyte.

CHUMBAWAMBA

A number of rather more memorable songs are based on ‘appeals’ to Dylan to ‘speak out’, as he once did, about political issues. In the late ‘60s and early 70s, Dylan was largely absent from the live music scene, releasing relatively ‘lightweight’ albums and making very few public appearances. Country Joe McDonald’s rather bizarre piece of ‘hippie nostalgia’ Hey Bobby (released as early as 1970 but still referring to ‘the good old days’) laments Dylan’s retreat from ‘the scene’. Joan Baez, who had never disguised her disappointment when Dylan turned away from political activism, composed the song To Bobby (1972) which was a clearly heartfelt but rather saccharine, if perhaps hopeless, appeal to her ‘Bobby’ to return to his former position as a supposed ‘leader’ of the political activist movements which she, to her great credit, continued to be involved in. The song has a lovely melody and is delivered in Baez’s usual immaculate tones. Baez makes rather obvious references to A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall and The Times They Are a-Changin’ and ends with a blatant attempt to ‘guilt trip him’ by implying that the world’s starving children are crying for him to return to his prophetic role. In the later Winds of the Old Days (1976) a more self-aware, post Rolling Thunder Baez begins by lamenting …those eloquent songs from the good old days/ That set us marching with banners ablaze… But now she is more self-deprecating, referring ruefully to her own ‘self-righteousness’, surely regretting releasing the rather embarrassing earlier song.

Another composition in the same vein, which is one of the best known ‘Dylan tributes’, is David Bowie’s Song to Bob Dylan from his brilliant 1971 album Hunky Dory, which also contains ‘tributes’ to Andy Warhol and the Velvet Underground (Queen Bitch). The song is a highly accomplished pop confection. Bowie memorably describes Dylan’s voice as being …like sand and glue… Its most moving line is the archly observed: …Gave your heart to every bed sit room/ At least a picture on the wall… But then Bowie proceeds to appeal to Dylan to …Give us back our unity, give us back out family/ You’re every nation’s refugee… This is perhaps rather strange coming from Bowie, who was never a ‘political’ songwriter. Even more bizarre is the song’s chorus: …Here she comes, here she comes, here she comes again/ The same old painted lady from the brow of the super brain…. There is a little bit of Bowie’s current interest in Nietzschean philosophy thrown in here, but it is downright weird for Bowie to imply that Dylan had been corrupted by showbiz, personified as that ‘same old painted lady’, especially considering that Bowie himself was about to make it big in a dazzling array of stage costumes in which he often appeared as nothing less than an (admittedly rather alluring) ‘painted lady’ himself.

DAVID BOWIE

The greatest songs about Dylan tend to be either celebratory or rather whimsically sad. Roger McGuinn’s Take Me Away (written with Dylan collaborator Jacques Levy) (1976) is a highly exuberant account of the great elation he experienced as part of the Rolling Thunder Tour (which he describes as a ‘band of gypsies’) of a few months before. …You’d’a swore for sure the circus came to town… he sings …There were ladies ridin’ bareback/ And the mystery man all painted like a clown… He describes himself …slippin’ from state to state/ Ending’ up in a drunken state of grace… The song is moving and economical, but expresses both joy and a certain sadness that this magical adventure is now over.

Ralph McTell’s Zimmerman Blues (1973) is a powerful and sadly reflective description of the travails of a performer like himself who has suffered greatly from ‘a life on the road’ where he was, nevertheless …happy, hungry and cold… McTell identifies the ‘burn out’ that he himself has experienced from this life as ‘the Zimmerman Blues’. Like other songwriters of the period (most notably Jackson Browne with his movingly poetic lament Before the Deluge) he also reflects back on how much of the idealism of the 1960s has now turned sour: …As sure as the stars turn above, all we ever asked for was love/ And I think that we’ve all been used…. McTell is quite honest about identifying himself as being rather lower down the hierarchy of singer-poets, expressing perhaps a certain regret at this but finally concluding that the emotional price that ‘Zimmerman’ must have paid would have been too much for him: …So where do we go from here?/ For me it won’t ever get that near/ But if it did I know what I would choose/ Anything but the Zimmerman Blues… The last line is then repeated eight times for emphasis, leaving us in little doubt of McTell’s humility.

RALPH McTELL

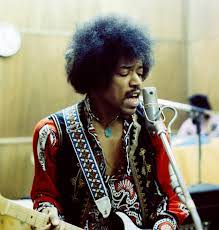

Jimi Hendrix, apart from being universally acknowledged as the greatest guitarist ever, was also arguably Dylan’s most powerful interpreter. His performance of Like a Rolling Stone at the 1967 Monterey Festival is an audaciously original take on a song that very few interpreters have managed to handle the complicated dynamics of. He also cut a version of Can You Please Crawl out Your Window for a BBC session and an electrified Drifter’s Escape. His All Along the Watchtower is one of the most powerful pieces of rock music ever recorded. Dylan admired it so much that the thousands of live versions of the song he played were based on Hendrix’s arrangement. Hendrix’s own personal tribute to Dylan, Highway Chile, was to be found on an early ‘B’ Side. It is one of Hendrix’s most impressive compositions, kicking off with one of his patent and unforgettable guitar licks. The song rides riding on an irresistible riff and is punctuated by a typically memorable guitar solo. Hendrix makes knowing references to the ‘Highway Chile’ as a ‘rolling stone’ whose …flamin’ hair is a-blowin- in the wind… He mythologises Dylan, portraying him as a hobo who …left home when he was seventeen… and who …left the world behind… But the real tribute lies in the perfectly controlled wildness of the music and its evocation of Dylan as a rebel hero. …Now you’d probably call him a tramp… the chorus begins …But I know it goes a little deeper than that….

JIMI HENDRIX

And finally we return to Joan Baez, who has always been known primarily as an interpretive artist, albeit one whose career and life was transformed by her encounter in the early 1960s with Dylan. She contributed considerably to making him famous by introducing him at her concerts, to the considerable bemusement of some of her fans. They sang together at the 1963 March on Washington at which Martin Luther King delivered his …I Have a Dream… speech and later at the Newport Folk Festivals in 1963 and 64. For a short time their rather public relationship led to them being dubbed the ‘King and Queen of Folk Music. But by 1965, Dylan had moved away from political song writing and activism and was about to ‘go electric’. Later that year, in a secret ceremony, he married Sara Lownds. It was clear from songs like To Bobby that, despite her own complicated love life in the years that followed, she was still absolutely in thrall to him, even though by now they had very little contact with each other. Then one day in 1975, completely out of the blue, she had a phone call…

Baez’s song Diamonds and Rust (released in 1976 but performed regularly on the first Rolling Thunder Tour in late 1975) is generally acclaimed as her most accomplished composition. She has played it at virtually every concert since, usually with some words of explanation. Although Dylan is never mentioned by name, there is no doubt that the song is an account of her thoughts about her reconnection with Dylan in the mid ‘70s. Baez later played a key role in the Rolling Thunder tour. As well as performing her own material, she engaged in duets with Dylan on a nightly basis which were far more musically successful that when they sang together in 1963-64. In those earlier days Baez’s high contralto often clashed awkwardly with Dylan’s ‘voice of sand and glue’. But by 1975 Baez’s vocals had hardened somewhat and Dylan – following his ‘country’ period – now sang in a decidedly softer tone. Their harmonies on Dylan songs like I Dreamed I Saw St. Augustine and I Shall Be Released and on covers like The Water is Wide and Never Let Me Go were exquisite. Baez even played a prominent role in Dylan’s film of the tour Renaldo and Clara. But the Rolling Thunder tour was a specific project in which Dylan involved many of his old compatriots from the ‘60s. After it was over, they rarely sang together again.

Diamonds and Rust is such a compelling song because of the complexity of the emotions it conveys. Here Baez truly lays her heart on the line. We can be in no doubt at all that she was, is and always will be utterly in love with Dylan, but that she now realises that any new relationship will be impossible. She takes us through the feelings she experienced during their ‘reunion’ with very striking emotional honesty. The drippy idealism of To Bobby is long gone. It is clear that the encounter with the real Bob Dylan, rather than the mythic figure she had created of him in his absence, has been cathartic for her. The song has a stirring melody, which beautifully suggests hope tinged with sadness and finally self-realisation. Its lyrics have an economy and a precision worthy of Dylan himself.

Baez conducts a kind of internal monologue with herself throughout the song. …Well I’ll be damned, here comes your ghost again/ But that’s not unusual, it’s just that the moon is full/ And you happened to call… At first she rationalises with herself that this is just an old friend calling her. The initial ‘well, I’ll be damned’ is a common colloquial expression, but hints at darker themes. Will she be ‘damned’ – or destined to suffer tragic consequences – if she allows herself to admit her love for ‘the caller’? The contrast in the second line, in which she attempts to normalise what is happening but in the context of a full moon – representing, of course, the madness of unrestrained passion, especially in women – is brilliantly understated. Then she takes us directly into the present moment: …Here I sit, hand on the telephone/ Hearing a voice I’d known/ A couple of light years ago/ Heading straight for a fall… The faux-jokey reference to ‘light years’ continues the ‘cosmic’ imagery. But in the last line we experience with her the rising hope (and at the same time, the hopelessness) that their love might be renewed.

Then, in a distinctly Dylanesque way, she jumps back through time. She is still talking to him on the telephone, but her mind is racing back through the excitement, the ecstasy and the disappointment that she experienced with him ‘all those years ago’. At first this is interspersed with a few snippets of the ‘present day’ conversation. One of the most remarkable things about the song is the way in which Baez recognises her own failings. The line …I remember your eyes were bluer than robin’s eggs… is of course a ‘corny’ one which reveals not only her intense love for him but her naivety as a younger woman. This is immediately undercut by the next line, which is clearly something Dylan once said to her that she is now remembering …Your poetry was lousy, you said… Of course, he is correct. Yet the way she has put these two lines together succeeds in putting the real nature of their relationship in a nutshell. She is open hearted. But he is sharp, even cruel, to her. It is obvious to any listener now that this relationship could never really have worked and will not do so in the future. But this still does not stop her being besotted with him. Baez tries to deflect these thoughts by returning to mundane conversation. This time she presents the two figures speaking in terse lines …” Where are you calling from”/”A booth in the mid west..” The mid-west is where Dylan originates from. In With God on Our Side’s memorable opening lines he calls it …the country I come from…

This ‘return to reality’ is only temporary. For the rest of the song Baez surrenders to a cavalcade of overwhelming memories of her relationship with Dylan. These are realised with great intensity, but are delivered with precision and much dramatic irony. For the rest of the song she retreats into her memories, which she now views through the prism of bitter experience. She has a fond memory buying him some (perhaps diamond encrusted?) cuff links. But then she finds herself warning that ‘voice on the telephone’ that …we both know what memories can bring/ They bring diamonds and rust… both beauty and decay… She then sinks further into nostalgic recollection, remembering Dylan’s early years of fame in vivid, slightly mocking but warmly delivered lines: …You burst on the scene already a legend/ The unwashed phenomenon, the original vagabond… She then gives a brief overview of their relationship, admitting it only happened because he was …temporarily lost at sea… In a reference to the last verse of Visions of Johanna (which many took to be a reference to her) she declares …the Madonna was yours for free… portraying herself, perhaps self-mockingly, as the embodiment of ‘purity’. This is followed by another self-characterisation: …Yes the girl on the half-shell could keep you unharmed… This is a reference to Botticelli’s famous painting of Venus, the goddess of love, emerging naked and fully formed from the sea, blown by Zephyr the wind god. These lines are also effective not only because Baez seems prepared to mock her own public image but also because of the way she reveals her own emotional fragility in Dylan’s presence. The reference to ‘keeping him unharmed’ seems to be another rather self-mocking reference to her own well reported tendency to ‘mother’ the often scruffily ‘unwashed’ singer.

The next two verses contains perhaps the song’s most powerfully evocative images. Baez takes us back to a wintry scene in which they are staying together …in a crummy hotel in Washington Square… referencing a well known location in Greenwich Village Then there are the literally ‘breathtaking lines: …Our breath comes out white clouds/ Mingles and hangs in the air…. Here their ‘mingled’ breath symbolises their emotional ties. It is as if she is desperately trying to ‘freeze’ that memory in her mind, hoping it will last forever. But this memorable image is undercut by the knowingly self-deprecating …Speaking strictly for me/ We both could have died then and there… She wishes the moment to be preserved for eternity. In writing these words she has, perhaps, succeeded in doing so. This is especially poignant because she clearly identifies the transcendent feelings as belonging to her alone.

This level of complex self-awareness lifts Baez’s song writing onto a new plane of self-awareness. In the beautiful image of the white clouds mingling, she immortalises their relationship. But she is never naive enough to think that this moment can really be recreated. In the last two verses she turns her ire on Dylan, trying to get under the surface of his notoriously evasive personality: …Now you’re telling me you’re not nostalgic/ Then give me another word for it/ You who are so good with words/ And at keeping things vague… Here again the dynamics of the relationship are revealed. She is utterly enraptured by his poetic nature and his soulfulness, but extremely frustrated by his equivocal attitudes and ambiguous pronouncements. She confesses that …I need some of that vagueness now/ It’s all come back too clearly… By this point we can imagine she is truly in tears, letting all those years of frustration out in this hopeless plea. But finally she recovers her composure. There seems to be a suggestion that he may be, in his rather ‘vague’ way, suggesting that they rekindle their relationship. But she tells him that …If you’re offering me diamonds and rust/ I’ve already paid…

Perhaps we may believe her. She is refusing to be taken in by the beguiling words of this man who is ‘so good with words’. But the song’s exploration of her own personal contradictions, and its evocation of her own longing, is so strong that we surely know that she is merely putting up a defence. It is the fact that she is prepared to expose her own emotional vulnerability that makes the song so powerful. Diamonds and Rust was released at a time when female singer songwriters were becoming more prominent. The song’s emotional complexity is reminiscent of the work of Joni Mitchell on albums like Blue, For the Roses and Court and Spark, in which she analysed the dynamics of her own relationships with great irony and commitment. Yet Mitchell is always a little more distant from her subjects, looking back obliquely on one relationship as she moves on to another. Baez’s song is so moving partly because we know exactly who she is singing about, and the fact that she is not hiding behind any ‘characters’ or ‘unreliable narrators’. Even though Dylan is never named in the song, there is no doubt who it is addressed to.

Thus the greatest song about Bob Dylan is the one in which a fellow ‘legendary’ performer actually reveals to us her personal and intimate knowledge of the man. Yet Baez manages to do this in a way that is never cloying or sentimental. And while the song is tinged by a kind of ineffable sadness that the great love she feels can never be truly realised, this is tempered by a certain awe of her subject that even she feels.

DAILY DYLAN NEWS at the wonderful EXPECTING RAIN

THE BOB DYLAN PROJECT- COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

Leave a Reply