BOB DYLAN AND WOODY GUTHRIE: IN THE GRAND CANYON AT SUNDOWN (Part Two)

EXTRACTS (Full text here)

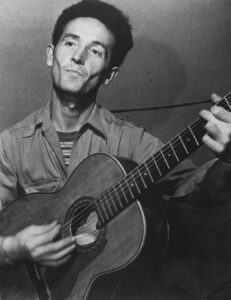

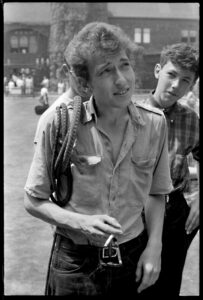

Guthrie’s ‘free form’ prose was in many ways a precursor to the novels of the Beat writers, especially Jack Kerouac’s On the Road. In its carefree mixing of truth and fiction and its colloquial style, it is also a clear precursor of Dylan’s equally fanciful Chronicles Part One (2004). All accounts of this period describe how after reading the book Dylan became obsessed with Guthrie. Soon his set lists became dominated by Guthrie compositions. It seems that, in order to impress fellow folk singers, promoters and fans he had adopted a Woody-like persona, even sometimes attempting to speak in an ‘Okie’ accent. In early 1961, when he arrived in New York, he visited his hero in hospital. Later he attended weekends in East Orange, New Jersey at the home of Guthrie’s friends Eve and Mac McKenzie, at which Guthrie was in attendance. During his initial run of dates in New York coffee houses in 1961 he had included many Guthrie songs in his shows. As his proficiency as a performer improved and developed rapidly at this time, he also adopted a similar vocal approach, delivering lyrics in a harsh and uncompromising tone that would set a pattern for his entire career. In the coffee houses he also closely watched Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, a performer whose style had been learned from Guthrie, and adopted many of his vocal mannerisms.

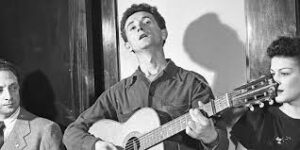

Woody Guthrie was active as a songwriter from the mid 1930s to the mid 1950s, after which he was hospitalised. During this period he was extraordinarily prolific, composing around a thousand songs, as well as travelling and playing with other leading folk artists like Pete Seeger, Cisco Houston and Leadbelly. He was influenced by early country music pioneers like Jimmie Rodgers and The Carter Family, as well as by many black blues singers. Politically he leaned to the left, although there is no record of him actually becoming a card carrying communist. But much of his writing was devoted to exposing how the poor in the USA were being exploited, most specifically regarding the plight of the Okies caught in the Dustbowl. He also composed a number of songs encouraging workers to join unions. After America entered the Second World War he turned out many anti-fascist songs and even famously inscribed the much imitated slogan ‘THIS MACHINE KILLS FASCISTS’ on his guitar. It was probably only his illness that prevented him from becoming a victim of the McCarthyite witch hunts of the 1950s.

Among the Guthrie songs that Dylan performed in the coffee houses of Minneapolis and New York in 1960-61 were Jesus Christ (in which Guthrie recasts Jesus as a ‘hard working man’ who was put down by the ‘bankers’), Pastures of Plenty (a highly poetic expression of the plight of Okie fruit pickers), Ramblin’ Round and Hard Travelin’ (in which the narrator explains his ‘travelling man’ persona), Pretty Boy Floyd and Jesse James (both songs romanticising outlaws) and a plethora of children’s songs and ‘talkin’ blues’ numbers. Whereas later in his career Dylan would be fond of heavily rearranging his cover versions, he generally treats the Guthrie songs with reverence, imitating his arrangements and vocal style. An exception to this is his treatment of Guthrie’s most famous work This Land is Your Land, which is often treated as a flag-waving, sing-along anthem, at his first major concert at the Carnegie Chapter Hall in November 1961. Dylan’s reading (released on The Bootleg Series Vol. 7) is slow and mournful, as he makes absolutely sure that the audience understands the song’s stark demands for equality and freedom.

Song to Woody is the song of a young man paying tribute to his legendary elders. It is without doubt Dylan’s first significant composition, communicating a very profound and genuine love, as well as immense respect, for Woody himself. The remarkable final lines, however, with their pronounced humility, already appear to acknowledge that Dylan himself has led a very different life to his mentor. Therefore what follows in his career is bound to diverge from Woody’s path. He is not destined, like Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, to become one of the ‘sons of Woody Guthrie’.

By 1963, Dylan had written so many of his own songs that he was no longer covering Guthrie material. In the years that followed he rarely returned to them, even during the 1990s when he played hundreds of folk and blues songs by other artists. This Land is Your Land, however, was used as the finale during the first part of the Rolling Thunder Tour in 1975. In 1976 he played Deportee as a duet with Joan Baez. In 1988 he recorded a stunning version of Pretty Boy Floyd, full of unique vocal gymnastics. In 2009 he played Do Re Mi, a cynical black comic discourse on American materialism for a charity show. The apparent lack of attention to Guthrie’s work in his later career may seem surprising, but it seems that fairly early in his career Dylan reached the point where he needed to go beyond Guthrie’s influence. At his concert at New York Town Hall in October 1963, when called back for an encore, instead of turning out one of his own ‘hits’ he explains to the audience that he has been asked to wrote a short testimonial for a forthcoming book to explain what Woody meant to him, but that there is no way he can keep to the assigned twenty five word limit. Then, for the only time in his career, he performs his ‘epic’ poem Last Thoughts on Woody Guthrie onstage.

Last Thoughts is a remarkably powerful piece which, although entirely spoken, is filled with musical cadences and could easily – but for its length – be performed with musical backing. What is perhaps most surprising, however, is that the poem tells us virtually nothing about Guthrie. There are no references to any of his songs, his autobiography, or his life story. Dylan makes no mention of Woody’s experiences in the Dustbowl, his ‘hard travelin’ around the country, his political views or the origins of his musical style. Instead, the poem is an intensely personal response to that question about Woody. It is a summation of Guthrie’s influence which thus stands squarely between Dylan’s past and his future.

The poem is around 200 lines long. Dylan delivers it in seven minutes, at quite a frenetic pace. Its form resembles the long works of Allen Ginsberg such as Howl and Kaddish, although Dylan relies more on rhyme and pararhyme. The tone of the language is colloquial. The rhymes are delivered at random intervals, in a way that keeps drawing the listener’s attention back to the words. The driving rhythm is constant, keeping mostly within the eight bar structure that dominates blues and rock music. The poem is full of random imagery; some of it a little awkward. But there are many effective collocations of words. Like much of the work of the Beat poets, Last Thoughts gives the impression of being a spontaneous, improvised composition which could easily be delivered over a jazz backing. The poem is addressed to society in general as well as to the poet himself. Most remarkably, it expresses a continuous pattern of thought, to the extent that it is almost like an extremely long sentence. The use of the second person address is maintained throughout. Dylan begins with a lengthy diatribe against the ills of the modern world, especially the culture of American commercialism and advertising. He castigates the shallowness of the contemporary culture around him in no uncertain terms. He then advises the ‘you’ character being addressed as to how to rise above the strictures of contemporary life that he has just listed. There is no doubt that the emotions Dylan conveys in the poem are deeply personal. Although the sole reference to Woody Guthrie comes right at the end, he attempts to identify and empathise with Guthrie’s world view, railing against the superficiality of a world blinded by materialistic values.

From the outset, the poem focuses on figures who are society’s victims: …When yer head gets twisted and yer mind grows numb/When you think you’re too old, too young, too smart or too dumb… Dylan throws in a plethora of metaphors, apparently chosen at random, to express the position of the confused and downtrodden, for whom life is described as a ‘slow motion crawl’. He pities those for whom …the wine don’t come to the top of your cup…He uses imagery of wind blowing, trains running, streets being curved rather than straight, the …reins on your pony slipping… Deserts and valleys are transformed into depressing urban chaos. Then he goes into full on Guthrie mode, in lines of extended pararhyme that could have come from Bound for Glory: …And the lightnin’s a-flashing and the thunder’s a-crashin’/ And the windows are rattlin’ and breakin’ and the roof tops a-shakin’/ And yer whole world’s a-slammin’ and bangin’… Then we hear the voice of the subject of the poem, as he moves seamlessly from second to first person: … to yourself you sometimes say/ “I never knew it was gonna be this way/ Why didn’t they tell me the day I was born?”.

The rest of the poem concerns a search for personal fulfilment in what seems to be a hope-starved world. As we begin to move towards a conclusion, the pace of the reading quickens. Dylan begins a long rant against the fake nature of much of materialistic contemporary culture, explaining how so much fails to provide the indefinable quality he is searching for. We learn that hope cannot be found ‘on a dollar bill’, in big stores full of material goods, in what (presumably referring to the sanitised nature of much of American cinema) he metaphorically describes as ‘Hollywood wheat germ’ or in the mindless entertainment provided in night clubs. Some of the funniest lines follow, as Dylan, in search of what he calls ‘hope’, declares: …It ain’t in the pimple-lotion people are sellin’ you/ And it ain’t in no cardboard-box house/ Or down any movie star’s blouse… He rails against the …dime store dummies or bubblegum goons… and attacks society’s manipulators and tricksters who try to sell various forms of false hope, as well as the ‘middle men’ who exploit artists: … the no-talent fools/ That run around gallant/ And make all rules for the ones that got talent… This section reaches a climax as he declares dramatically: …Ain’t there no one here that knows where I’m at/ Ain’t there no one here that knows how I feel/ Good God Almighty, THAT STUFF AIN’T REAL!!”

The quality that Dylan defines as ‘hope’ can, it seems, only be found in the kind of authenticity that Guthrie represents. The poem ends with Dylan asking, in a number of different ways, where this ‘hope’ can be found, until he finally gives us his highly equivocal answer, bringing the poem to a highly memorable conclusion: …You’ll find God in the church of your choice/ You’ll find Woody Guthrie in Brooklyn State Hospital/ And though it’s only my opinion, I may be right or wrong/ You’ll find them both in the Grand Canyon at sundown… From this moment onwards, Dylan’s artistic leanings will begin to shift. Having composed the many striking (and decidedly Guthriesque) ‘protest songs’ that have made his name, he will now begin to write far more personal material. His musical style will soon evolve away from the basic approach of ‘guitar-harmonica-vocals’ that he had borrowed from Guthrie, both upsetting and revolutionising the folk music ‘community’ as he does so. It seems as if, by composing this poem, he has realised that the real lessons he have learned from Guthrie are not just social or political. Woody has taught him to be true to himself, to follow his own path wherever it leads. Now he can move on towards creating some of his most resonant work, having shaken off the need to follow Guthrie’s specific example.

In these profound Last Thoughts, Dylan appears to have truly understood Woody’s philosophy of life. The beautiful final image (which is itself redolent of the nature-patriotism of This Land is Your Land) indicates that to Dylan, Guthrie has been not only an artistic and emotional but also a kind of ‘spiritual master’ whose ghost will always be at his shoulder, overlooking his songs – mostly (but perhaps not always) giving approval.

Leave a Reply