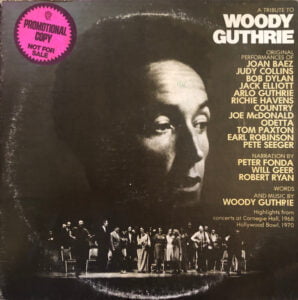

January 20th 1968. The crowd in New York’s ornately furnished Carnegie Hall is mostly a respectable-looking bunch. Shirts and ties and ironed dresses abound. The gathering has been arranged in honour of the recently deceased Woody Guthrie. Poor Woody had spent over a decade in various hospitals, suffering from the effects of Huntingdon’s Disease, an inherited degenerative ailment. In the meantime his reputation as the ‘godfather’ of American folk music had grown considerably, not least through Bob Dylan’s very public patronage in his early career. Now the faithful are gathered to pay tribute. The cast of players is star studded, featuring many of the major figures of the American folk scene. Most of them, as you would expect, use acoustic instruments. Judy Collins delivers highly spirited renditions of So Long (It’s Been Good To Know Ya), Deportee and Union Maid. Richie Havens sings the haunting Vigilante Man, Tom Paxton brings his sweetly ironic tones to Pastures of Plenty and The Great Historical Bum, Ramblin’ Jack Elliot performs the children’s song Howdido and Pete Seeger the charming ditty Curly Headed Baby. Odetta lends her powerful tones to Ramblin’ Round before leading the climactic sing-along chorus of This Land is Your Land that closes the show. In between the acts, Hollywood actors Will Geer and Robert Ryan read extracts from Woody’s writings.

PETE SEEGER, BOB DYLAN, JUDY COLLINS AND ARLO GUTHRIE

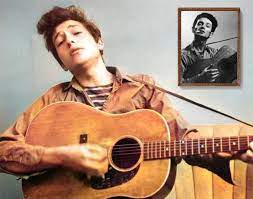

There is little doubt, however, who the main attraction is tonight. It is the first time Bob Dylan has appeared in public since the epochal 1966 tour and few of the audience know what to expect. He had recently released the laid back John Wesley Harding album, but this will not give them any clues as to the nature of his performance. Towards the end of the first half of the show, he shambles onstage in a grey suit and open necked shirt, his wild ’66 locks shorn. He now sports a short, rather stringy beard, giving him the appearance of an itinerant preacher fallen on hard times. Behind him five similarly attired musicians line up, mostly dressed in black. Within a few months, The Band’s first album Music from Big Pink will be released. But for now these musicians are more or less unknown to an audience which is, like the rest of the world, completely unaware that Dylan – supposedly recuperating from his motorcycle accident – has been writing and performing literally hundreds of songs with them in a secluded location in upstate New York. It is only two and a half years since Dylan’s infamous appearance at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965 but the culture of popular music has experienced a revolution since then. No objections by the folkies to the appearance of backing musicians are expected this time.

DYLAN AND THE BAND

The three song performance could be said to be a kind of declaration of peace with the folk community, who he had stirred up so much in recent times. Yet this is being done on Dylan’s own uncompromising terms. It is no impromptu performance. The arrangements have clearly been worked out in detail and The Band’s timing is immaculate. The music is loud and uncompromising, subjecting two well known and one obscure Guthrie numbers to the full band treatment, although it is arguably more nuanced, with more light and shade, than the full on attack which these musicians (minus the now-returned drummer Levon Helm) presented on the ’66 tour, as they railed angrily against anti-rock protesters.

It is still somewhat disconcerting, however, to hear this material – rooted as it is in the culture and politics of the 1930s and 40s – as rock. The music hints at the dazzling eclecticism which will distinguish The Band’s first two albums. Dylan’s delivery is highly committed and impassioned. The Grand Coulee Dam, an exuberant celebration of a giant construction project, is distinguished by notable interjections by Garth Hudson on organ, while the lyrics celebrate American industry and endeavour during World War Two, describing the dam as one of the ‘seven wonders’ of the modern world. The song reflects the expansive Whitmanesque patriotism that marks much of Guthrie’s work. The Band’s three singers Richard Manuel, Rick Danko and Levon Helm provide sterling vocal support on the rousing choruses.

I Ain’t Got No Home is a very angry protest song that dramatises the plight of an itinerant worker during the Great Depression. It does not stint at criticising the authorities. The chorus runs …Police make it hard, wherever I may go… Dylan thoroughly inhabits the persona of the dispossessed narrator as he attacks the song with venom, making sure every word is heard. This is partly possible because amplification has improved considerably since the ’66 tour. The dominant instrument is Manuel’s piano. Robbie Robertson plays a fluid guitar solo towards the end and the song concludes with another stirring harmonic flourish which emphasises the singer’s desperation.

ELEANOR ROOSEVELT AND FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT

Dear Mrs. Roosevelt is the most surprising selection. This extraordinary tribute to the late American President was never recorded by its author. It pretends to be one of the many letters that members of the public wrote to Eleanor Roosevelt, perhaps the most politically active First Lady, who had campaigned actively against racism and poverty. She was also a devotee of folk music and thus perhaps a ‘fan’ of Guthrie himself. The song is a kind of love letter to the President who – despite being ‘struck down by the fever’ of polio – guided the US through World War Two and whose New Deal economic policy is said to have helped America recover from the Great Depression. Dylan treats the song with absolute sincerity. He sings more melodically here, pacing himself carefully, with The Band again supporting him on the chorus: …This world was lucky to see him born!…

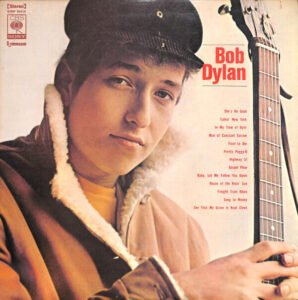

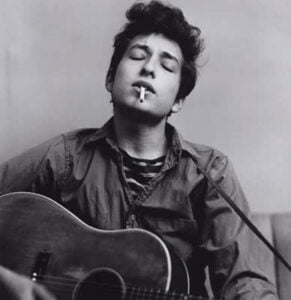

Song to Woody is one of just two Dylan compositions on his first album, released in 1962. He is described on the sleeve notes as a ‘country blues’ singer. The rest of the material on this incendiary debut tends to confirm this. The album features ‘hard blues’ in the form of Blind Lemon Jefferson’s See That My Grave is Kept Clean, Bukka White’s Fixin’ to Die, Blind Willie Johnson’s In My Time of Dying and Curtis Jones’ Highway 51. There are also more light hearted blues-flavoured songs such as Eric Von Schmidt’s Baby, Let Me Follow You Down, Jesse Fuller’s You’re No Good and the ‘hillbilly blues’ number Freight Train Blues – along with spirited takes on traditional American folk songs like The House of the Rising Sun, Pretty Peggy-O, Gospel Plow and Man of Constant Sorrow.

It is perhaps surprising that no Woody Guthrie covers appear on the album. But Dylan’s own Talkin’ New York uses the ‘talking’ blues’ format that Woody popularised to give a jaunty account of his own arrival in New York City in the icy cold winter of the previous year. …I froze right to the bone… he tell us. Then, borrowing a little from Chuck Berry, after a …rockin’ , rollin’ reelin’ ride… he lands in the place that he deliberately mispronounces as …Green-wich village… Already he sounds quite cynical about attitudes to ‘folk music’ in the coffee houses as he gets turned down by one proprietor: …You sound like a hillbilly. We want folk singers here… implying that he is expected to play the then-popular commercial and often bowdlerised form of the music which had brought some success to groups like The Kingston Trio. ‘Hillbilly’ music was a popular name for country and western, which the proprietor appears to be implying, is not ‘real’ folk music.

Dylan then describes how he gets a job playing harmonica for …a dollar a day… In the penultimate verse he explains how he finally gets a better paid job in a larger venue, having …joined the union and paid my dues… This is a nod to Guthrie, who was a lifelong committed socialist. The following lines do not mention Woody by name, referring to him as ‘a very great man’ who once said that …Some people rob you with a fountain pen… This is a direct reference to Pretty Boy Floyd, one of the many Guthrie songs Dylan had been performing in the clubs. Talkin’ New York could hardly be called a ‘protest’ song but already Dylan has taken on Guthrie’s satirical tone, laced with cutting humorous asides. He relates a similar tale in Hard Times in New York Town (unreleased until 1991) in which he refers to the …mighty many people all millin’ all around/ They’ll kick you when you’re up and knock you when you’re down…

FOLKWAYS TRIBUTE TO WOODY GUTHRIE 1988

In these songs Dylan adopts elements of his mentor’s biography. Talkin’ New York begins …Ramblin’ outa the Wild West/ Leavin’ the towns I love the best… In Hard Times in New York Town he refers to … the smog in Cal-i-for-ne-ay/ ’N’ every bit of dust in the Oklahoma plains/ ’N’ the dirt in the caves of the Rocky Mountain mines… as if he himself has lived a life of ‘rambling’ like his hero. In his first ever radio interview with Oscar Brand in October 1961 he deliberately embellished this entirely mythical life story:

Bob Dylan I was raised in Gallup, New Mexico.

Oscar Brand Do you get many songs there?

Bob Dylan You get a lot of cowboy songs there. Indian songs. That vaudeville kind of stuff.

Oscar Brand Where’d you get your carnival songs from?

Bob Dylan Uh, people in the carnival…

Oscar Brand Do you travel with it or watch the carnival?

Bob Dylan Travel the carnival when I was about 13 years old.

Oscar Brand For how long?

Bob Dylan All the way up till I was 19 every year off and on I’d join different carnivals.

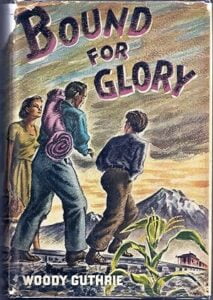

In a much longer radio interview with songs on Cynthia Gooding’s show Folksinger’s Choice in February 1962, Dylan continues to maintain that he worked in a carnival for seven years and had ‘rambled’ around the country collecting songs from various blues singers. He had begun to construct this ‘fantasy identity’ during his first forays into performing in the coffee houses of Minneapolis in 1960, adopting the name ‘Dylan’ instead of Zimmerman and hiding the fact of his upbringing in a respectable middle class Jewish home. Later that year he was introduced to Guthrie when a friend lent him a copy of his autobiography Bound for Glory (1943), a prose extravaganza including scenes of Guthrie travelling in box cars with fellow Okies during the ecological disaster of the ‘Dustbowl’ in the 1930s and experiencing with them the prejudice faced when they arrived in California to work as fruit pickers.

Guthrie’s ‘free form’ prose was in many ways a precursor to the novels of the Beat writers, especially Jack Kerouac’s On the Road. In its carefree mixing of truth and fiction and its colloquial style, it is also a clear precursor of Dylan’s equally fanciful Chronicles Part One (2004). All accounts of this period describe how after reading the book Dylan became obsessed with Guthrie. Soon his set lists became dominated by Guthrie compositions. It seems that, in order to impress fellow folk singers, promoters and fans he had adopted a Woody-like persona, even sometimes attempting to speak in an ‘Okie’ accent. In early 1961, when he arrived in New York, he visited his hero in hospital. Later he attended weekends in East Orange, New Jersey at the home of Guthrie’s friends Eve and Mac McKenzie, at which Guthrie was in attendance. During his initial run of dates in New York coffee houses in 1961 he had included many Guthrie songs in his shows. As his proficiency as a performer improved and developed rapidly at this time, he also adopted a similar vocal approach, delivering lyrics in a harsh and uncompromising tone that would set a pattern for his entire career. In the coffee houses he also closely watched Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, a performer whose style had been learned from Guthrie, and adopted many of his vocal mannerisms.

WOODY GUTHRIE

Woody Guthrie was active as a songwriter from the mid 1930s to the mid 1950s, after which he was hospitalised. During this period he was extraordinarily prolific, composing around a thousand songs, as well as travelling and playing with other leading folk artists like Pete Seeger, Cisco Houston and Leadbelly. He was influenced by early country music pioneers like Jimmie Rodgers and The Carter Family, as well as by many black blues singers. Politically he leaned to the left, although there is no record of him actually becoming a card carrying communist. But much of his writing was devoted to exposing how the poor in the USA were being exploited, most specifically regarding the plight of the Okies caught in the Dustbowl. He also composed a number of songs encouraging workers to join unions. After America entered the Second World War he turned out many anti-fascist songs and even famously inscribed the much imitated slogan ‘THIS MACHINE KILLS FASCISTS’ on his guitar. It was probably only his illness that prevented him from becoming a victim of the McCarthyite witch hunts of the 1950s.

Among the Guthrie songs that Dylan performed in the coffee houses of Minneapolis and New York in 1960-61 were Jesus Christ (in which Guthrie recasts Jesus as a ‘hard working man’ who was put down by the ‘bankers’), Pastures of Plenty (a highly poetic expression of the plight of Okie fruit pickers), Ramblin’ Round and Hard Travelin’ (in which the narrator explains his ‘travelling man’ persona), Pretty Boy Floyd and Jesse James (both songs romanticising outlaws) and a plethora of children’s songs and ‘talkin’ blues’ numbers. Whereas later in his career Dylan would be fond of heavily rearranging his cover versions, he generally treats the Guthrie songs with reverence, imitating his arrangements and vocal style. An exception to this is his treatment of Guthrie’s most famous work This Land is Your Land, which is often treated as a flag-waving, sing-along anthem, at his first major concert at the Carnegie Chapter Hall in November 1961. Dylan’s reading (released on The Bootleg Series Vol. 7) is slow and mournful, as he makes absolutely sure that the audience understands the song’s stark demands for equality and freedom.

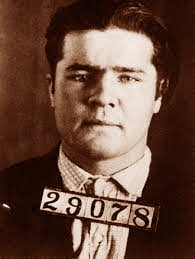

Many of Dylan’s early songs are Guthrie pastiches. Talkin’ Bear Mountain Picnic Massacre Blues, one of the compositions which led to Dylan becoming known as a songwriter, borrows not only its melody and but its overall structure and lyrical style from Guthrie’s Talkin’ Merchant Marine, an account of his wartime service as a sailor. Dylan was clearly influenced by Guthrie’s songs about contemporary events, many of which included thoughtful philosophical twists, often expressed with sardonic wit. Pretty Boy Floyd (which Dylan recorded a memorable version of for a Guthrie/Leadbelly tribute album in 1988) concludes with …I ain’t never seen an outlaw drive a family from their home… , thus identifying the bankers and capitalists as being much bigger villains than a mere outlaw. In Dylan’s Only a Pawn in their Game he identifies the society that created Medgar Evars’ murderer as the real villain rather than the murder himself. In With God on Our Side he concludes by asking the (perhaps unanswerable) question …Did Judas Iscariot have God on his side?… ..

PRETTY BOY FLOYD

Dylan’s singing style has always been controversial, despite the many changes it has gone through. But Dylan learned from Guthrie, as well as from many blues and ‘hillbilly’ singers, that songs that contained important messages would come over more effectively if the vocal delivery was abrasive. This meant that listeners could either listen to the message or reject the song. But in Guthrie’s aesthetic, messages were always more important than the melodies. Like many other folk singers, he quite happily ‘borrowed’ melodies from other songs, perhaps hoping that the familiarity of the music might help the message to be put over. Even This Land is My Land uses the melody of Oh My Loving Brother, a well known gospel hymn. Its tune also closely resembles that of the country standard You Are My Sunshine, first recorded by Jimmie Davis in 1940. Such practices, which Pete Seeger has identified as part of the ‘folk process’, have remained a feature of Dylan’s work throughout his career, often leading to misplaced accusations of plagiarism.

Perhaps the most important quality that Dylan imbued from Guthrie was that of authenticity. Although Dylan ‘made it’ as a result of his success in the Greenwich Village folk scene, it is hard to imagine how Guthrie would have fit in to the often dogmatic and patronising attitude of middle class folkies that Dylan himself railed against when he moved away from being a ‘folk singer’. Dylan was a famous star from a very young age – and certainly did not experience the physical and financial hardships that Guthrie went through – but he has always maintained a considerable distance between himself and the trappings of ‘showbiz’. He has avoided any kind of ‘celebrity lifestyle’, never appears on chat shows and (especially in his later career) has avoided the ways of getting easy applause from audiences that most rock performers employ.

Given that the young Dylan presented reporters, radio hosts and co-performers with a fictionalised account of his life, it is perhaps surprising that Song for Woody does not add to this mythology. In fact, Dylan is surprisingly honest and self deprecating here. He uses the tune of Guthrie’s harrowing 1913 Massacre, an account of the murder of strikers and their children which Dylan had performed at Carnegie Chapter Hall in 1961 (although Guthrie himself seems to have appropriated the lyric from the traditional song One Morning in May, otherwise known as The Bold Grenadier). The first verse makes it clear that Dylan sees himself as a ‘wandering minstrel’ in the Guthrie tradition: …I’m out here a thousand miles from my home… he begins, rather tentatively …Walking a road other men have gone down… He explains that he now sees the world through Guthrie’s perspective: …I’m seeing your world of people and things/ Your paupers and peasants and princes and kings… The expression ‘people and things’ is a little vague, but the following line, with its pronounced alliteration, is an effective summary of Woody’s view of human equality.

Dylan then addresses Woody directly: …Hey hey Woody Guthrie, I wrote you a song… The next line …About a funny old world that’s coming along… catches Guthrie’s tone exactly; the expression ‘funny old world’ may be something of a cliché but it expresses a part cynical, part humorous attitude (in imitation of Woody’s own tone) very effectively. The philosophical personification in the next lines: …Seems sick and it’s hungry, it’s tired and its torn/ It looks like its dyin’ and it’s hardly been born… could easily be a line from Bound for Glory. Dylan clearly indicates here that he identifies with Guthrie’s world view, which prioritises society’s underdogs and focuses on inequalities in the ‘sick world’ they live in. He admits that …there’s not many men that done the things that you’ve done… Again the expression may be a little vague but it is clearly completely heartfelt.

The penultimate verse pays tribute to some of the folk singers that Guthrie was associated with: …Here’s to Cisco and Sonny and Leadbelly too/ And all the good people that travelled with you… (referring to Cisco Houston, Sonny Terry and Huddle Ledbetter). These economical lines extend the respect Dylan shows to Woody to other contemporary folk pioneers that he admires. ..Here’s to the hearts and the hands of the men/ Who come with the dust and are gone with the wind… evokes Guthrie’s Dustbowl songs to describe a group of singers who bear witness to the plight of the disadvantaged in American society, despite the opprobrium placed upon them by politicians and other defenders and upholders of the status quo. Finally Dylan signs off by announcing that he will soon be, in true Guthrie style, taking to the road very soon. But he emphasises that …The very last thing that I’d want to do/ Is to say I’ve been hittin’ some hard travelin’ too… This is a neat twist, with a double meaning of ‘the last thing’ in which Dylan ruefully seems to be acknowledging that – despite the mythology he had built up around himself – his own life experience cannot really be compared to that of Woody or his fellow travellers.

Song to Woody is the song of a young man paying tribute to his legendary elders. It is without doubt Dylan’s first significant composition, communicating a very profound and genuine love, as well as immense respect, for Woody himself. The remarkable final lines, however, with their pronounced humility, already appear to acknowledge that Dylan himself has led a very different life to his mentor. Therefore what follows in his career is bound to diverge from Woody’s path. He is not destined, like Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, to become one of the ‘sons of Woody Guthrie’.

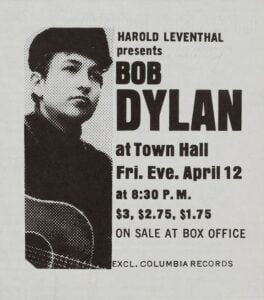

By 1963, Dylan had written so many of his own songs that he was no longer covering Guthrie material. In the years that followed he rarely returned to them, even during the 1990s when he played hundreds of folk and blues songs by other artists. This Land is Your Land, however, was used as the finale during the first part of the Rolling Thunder Tour in 1975. In 1976 he played Deportee as a duet with Joan Baez. In 1988 he recorded a stunning version of Pretty Boy Floyd, full of unique vocal gymnastics. In 2009 he played Do Re Mi, a cynical black comic discourse on American materialism for a charity show. The apparent lack of attention to Guthrie’s work in his later career may seem surprising, but it seems that fairly early in his career Dylan reached the point where he needed to go beyond Guthrie’s influence. At his concert at New York Town Hall in October 1963, when called back for an encore, instead of turning out one of his own ‘hits’ he explains to the audience that he has been asked to wrote a short testimonial for a forthcoming book to explain what Woody meant to him, but that there is no way he can keep to the assigned twenty five word limit. Then, for the only time in his career, he performs his ‘epic’ poem Last Thoughts on Woody Guthrie onstage.

Last Thoughts is a remarkably powerful piece which, although entirely spoken, is filled with musical cadences and could easily – but for its length – be performed with musical backing. What is perhaps most surprising, however, is that the poem tells us virtually nothing about Guthrie. There are no references to any of his songs, his autobiography, or his life story. Dylan makes no mention of Woody’s experiences in the Dustbowl, his ‘hard travelin’ around the country, his political views or the origins of his musical style. Instead, the poem is an intensely personal response to that question about Woody. It is a summation of Guthrie’s influence which thus stands squarely between Dylan’s past and his future.

The poem is around 200 lines long. Dylan delivers it in seven minutes, at quite a frenetic pace. Its form resembles the long works of Allen Ginsberg such as Howl and Kaddish, although Dylan relies more on rhyme and pararhyme. The tone of the language is colloquial. The rhymes are delivered at random intervals, in a way that keeps drawing the listener’s attention back to the words. The driving rhythm is constant, keeping mostly within the eight bar structure that dominates blues and rock music. The poem is full of random imagery; some of it a little awkward. But there are many effective collocations of words. Like much of the work of the Beat poets, Last Thoughts gives the impression of being a spontaneous, improvised composition which could easily be delivered over a jazz backing. The poem is addressed to society in general as well as to the poet himself. Most remarkably, it expresses a continuous pattern of thought, to the extent that it is almost like an extremely long sentence. The use of the second person address is maintained throughout. Dylan begins with a lengthy diatribe against the ills of the modern world, especially the culture of American commercialism and advertising. He castigates the shallowness of the contemporary culture around him in no uncertain terms. He then advises the ‘you’ character being addressed as to how to rise above the strictures of contemporary life that he has just listed. There is no doubt that the emotions Dylan conveys in the poem are deeply personal. Although the sole reference to Woody Guthrie comes right at the end, he attempts to identify and empathise with Guthrie’s world view, railing against the superficiality of a world blinded by materialistic values.

From the outset, the poem focuses on figures who are society’s victims: …When yer head gets twisted and yer mind grows numb/When you think you’re too old, too young, too smart or too dumb… Dylan throws in a plethora of metaphors, apparently chosen at random, to express the position of the confused and downtrodden, for whom life is described as a ‘slow motion crawl’. He pities those for whom …the wine don’t come to the top of your cup…He uses imagery of wind blowing, trains running, streets being curved rather than straight, the …reins on your pony slipping… Deserts and valleys are transformed into depressing urban chaos. Then he goes into full on Guthrie mode, in lines of extended pararhyme that could have come from Bound for Glory: …And the lightnin’s a-flashing and the thunder’s a-crashin’/ And the windows are rattlin’ and breakin’ and the roof tops a-shakin’/ And yer whole world’s a-slammin’ and bangin’… Then we hear the voice of the subject of the poem, as he moves seamlessly from second to first person: … to yourself you sometimes say/ “I never knew it was gonna be this way/ Why didn’t they tell me the day I was born?”.

The images of discontent then multiply. The subject is said to be ‘knee deep in water’ – not quite drowning yet. The strangely illogical line…the whole world’s a-watchin’ with a window-peek stare…seems to reflect on his own position as a famous person, whose privacy and therefore mental health is under considerable threat. The line …yer jackhammer falls from your hands to your feet…is an obscure reference to Guthrie’s song Jackhammer Blues, in which the implement symbolises the pride of the working man. Gambling terminology is also thrown in: …You were faked out an’ fooled while facing a four flush/ And all the time you were holdin’ three queens… The subject’s mind is left …bouncin’ around a pinball machine… Later a lion’s mouth opens, intending to devour him.

Dylan then switches to the first person as he portrays the subject questioning his entire life: …you say to yourself just what am I doin’/ On this road I’m walkin’, on this trail I’m turnin’/ On this curve I’m hanging/ On this pathway I’m strolling, in the space I’m taking/In this air I’m inhaling… We hear that the subject will try his very best not to allow all this self doubt to overwhelm him: …you try with your whole soul best/ Never to think these thoughts and never to let/ Them kind of thoughts gain ground/ Or make yer heart pound… Then the fact that he has indeed been addressing himself becomes pointedly obvious, as he refers to various musical instruments he is playing. He begins to ask himself some pertinent questions: …Who am I helping, what am I breaking/ What am I giving, what am I taking…

There is another switch back to second person as Dylan warns that, despite the pressures of the world that he has recounted, it is crucial to remain positive: …But you try with your whole soul best/Never to think these thoughts and never to let them kind of thoughts gain ground… One of the poem’s key lines is …You know that it’s something special you’re needing… Now he begins to search for solutions, employing more train imagery as he argues that … you need something special all right/ You need a fast flyin’ train on a tornado track/To shoot you someplace and shoot you back… Although he mentions social elements that need to be changed, such as …You need a Greyhound bus that don’t bar no race… the main focus is now on internal, rather than external truth. In some of the poem’s most crucial lines, we are told that …You need something to open your eyes/ You need something to make it know/ That it’s you and no one else that owns/ That spot that yer standing, that space that you’re sitting…

The rest of the poem concerns a search for personal fulfilment in what seems to be a hope-starved world. As we begin to move towards a conclusion, the pace of the reading quickens. Dylan begins a long rant against the fake nature of much of materialistic contemporary culture, explaining how so much fails to provide the indefinable quality he is searching for. We learn that hope cannot be found ‘on a dollar bill’, in big stores full of material goods, in what (presumably referring to the sanitised nature of much of American cinema) he metaphorically describes as ‘Hollywood wheat germ’ or in the mindless entertainment provided in night clubs. Some of the funniest lines follow, as Dylan, in search of what he calls ‘hope’, declares: …It ain’t in the pimple-lotion people are sellin’ you/ And it ain’t in no cardboard-box house/ Or down any movie star’s blouse… He rails against the …dime store dummies or bubblegum goons… and attacks society’s manipulators and tricksters who try to sell various forms of false hope, as well as the ‘middle men’ who exploit artists: … the no-talent fools/ That run around gallant/ And make all rules for the ones that got talent… This section reaches a climax as he declares dramatically: …Ain’t there no one here that knows where I’m at/ Ain’t there no one here that knows how I feel/ Good God Almighty, THAT STUFF AIN’T REAL!!”

The quality that Dylan defines as ‘hope’ can, it seems, only be found in the kind of authenticity that Guthrie represents. The poem ends with Dylan asking, in a number of different ways, where this ‘hope’ can be found, until he finally gives us his highly equivocal answer, bringing the poem to a highly memorable conclusion: …You’ll find God in the church of your choice/ You’ll find Woody Guthrie in Brooklyn State Hospital/ And though it’s only my opinion, I may be right or wrong/ You’ll find them both in the Grand Canyon at sundown… From this moment onwards, Dylan’s artistic leanings will begin to shift. Having composed the many striking (and decidedly Guthriesque) ‘protest songs’ that have made his name, he will now begin to write far more personal material. His musical style will soon evolve away from the basic approach of ‘guitar-harmonica-vocals’ that he had borrowed from Guthrie, both upsetting and revolutionising the folk music ‘community’ as he does so. It seems as if, by composing this poem, he has realised that the real lessons he have learned from Guthrie are not just social or political. Woody has taught him to be true to himself, to follow his own path wherever it leads. Now he can move on towards creating some of his most resonant work, having shaken off the need to follow Guthrie’s specific example.

THE GRAND CANYON AT SUNDOWN

In these profound Last Thoughts, Dylan appears to have truly understood Woody’s philosophy of life. The beautiful final image (which is itself redolent of the nature-patriotism of This Land is Your Land) indicates that to Dylan, Guthrie has been not only an artistic and emotional but also a kind of ‘spiritual master’ whose ghost will always be at his shoulder, overlooking his songs – mostly (but perhaps not always) giving approval.

Leave a Reply