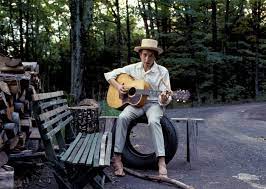

Tears of Rage represents a key turning point in Bob Dylan’s career. Written and recorded at some time between May and October 1967, when the focus of attention in the music world was on San Francisco and the ‘summer of love’, this sad, stately and incredibly moving song presents a new kind of mature aesthetic to a culture seemingly obsessed with a so called ‘youth revolution’. Dylan himself, through his protest songs of the early 60s and his mid-60s and his trilogy of masterpieces of ‘sound poetry’ Bringing it All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde had shone brightly as the most articulate ‘voice of youth’. Even now, he was just turning 26. But after he had pushed himself to the limits of hedonistic living, while fearlessly facing down critics who saw his move into ‘electric’ music as a purely commercial move, he had now retreated to the supposed anonymity of Woodstock, an artists’ community in upstate New York. He was now married, with a young family on the way. The music that he and his backing musicians (soon to be known as The Band) were experimenting with in what later became universally known as ‘The Basement Tapes’ represented a radical revision of the iconoclastic ethos that had characterised Dylan’s work of the previous three years. After working together on a range of country, blues and folk covers, Dylan and The Band began to record songs that were enigmatic and full of bizarre, sometimes random, images. At the same time they were strongly rooted in traditional sources, unlike the amphetamine-fuelled extravaganzas full of ‘chains of flashing images’ that had dominated his recent output.

In its tone, singing style and subject matter Tears of Rage is a radical shift for Dylan. On the Basement Tapes his voice is mellower and deeper than on Blonde on Blonde, which had been recorded just a year before. Like all the 1967 songs, it is concise, with only three verses and a repeated chorus. And whereas the final shows of ’66 had needed to be defiantly loud and raucous to drown out the ‘naysayers’ in the crowd, the musicians now play quietly, with considerable restraint. But it is the subject matter of the song which represents the biggest change. It is a kind of dramatic monologue, sung in the voice of anguished parents who react to the actions and attitudes of their rebellious daughter. Whereas once Dylan had rallied the cause of youth against the older generation, proudly declaring that …Your sons and your daughters are beyond your command… now he focuses on the incomprehension that so many parents experienced in the 1960s at their children’s attitudes to patriotism, war, sex, drugs and personal freedom and frames it within a tragic context.

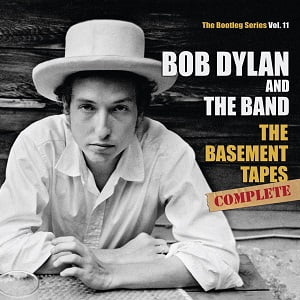

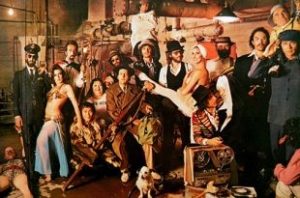

In many ways, Tears of Rage can be seen as a kind of ‘answer song’ to The Beatles’ She’s Leaving Home, one of the outstanding tracks on Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, which was released in May 1967; just as Dylan and The Band began recording in the basement of Big Pink. The album was instantly acclaimed as the group’s piece de resistance and is still revered today as the apex of the short lived era of psychedelic music. Dylan was later quoted as indicating that he was not impressed by the layers of production tricks and techniques that could be heard on the album. Grounded as he is in the ethos of the blues, he has always preferred a rawer, more spontaneous, approach to recording, so that his songs can be developed in live performance. It seems that, as soon as he heard Sgt. Pepper he decided that his own music would proceed in a radically different direction. Rather than adding psychedelic effects to his songs or producing classically-influenced ‘mini-symphonies’, as both The Beatles and the Beach Boys had done, he was now digging deeper and deeper into his own musical roots as he and his musicians worked through many covers of folk, blues and country songs. All of these were recorded, not on professional studio equipment, but on Garth Hudson’s trusty reel to reel tape recorder, for an uncertain posterity. The Basement Tapes were not released for another eight years, during which their existence spawned the nascent bootleg industry. Even then, only a selection of the songs appeared on the album, which was poorly mastered and left out a number of the key songs.

She’s Leaving Home is a heavily orchestrated track which tells the story of a teenage girl with rather overbearing parents who steals away from home one morning, leaving only a note, in search of ‘fun’, which is said to be …the one thing that money can’t buy… While Paul McCartney relates this story sweetly and tearfully against a background of sweeping strings, John Lennon rather sarcastically supplies the voices of the parents, who pathetically wail that …we gave her everything money could buy… Although we may feel sorry for the parents in the story, we are left in little doubt that the girl had to leave in order to escape her rather suffocating home life. Other songs on the album touch on similar themes. The apparently jaunty but rather subtly sad When I’m Sixty Four and With a Little Help From My Friends, whose narrator relies on his acquaintances with a similar ideology to him, who will ‘get him high’ and help him to ‘get by’, rather than his family. Childhood itself is idealised in the ‘cartoon acid fantasy’ Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds, while in Within You, Without You the listeners are impelled to follow the tenets of Eastern philosophies in order to bring about change in themselves. In the climactic A Day in the Life, listeners have their ‘minds blown’ in a psychedelic explosion. The older generation, who approved of the ‘mop tops’ when they were cheeky, cheery pop stars in their early days, were not so sure about them now…

Sgt. Pepper went on to become one of the most influential albums of all time, spawning the entire genre of 1970’s ‘progressive rock’ and virtually inventing the notion of a ‘concept album’. Yet Dylan, with typical perversity, had no interest in following such trends. Along with The Band, the music he was making in this era pointed in a very different direction, towards thoughtfulness, restraint, tradition and a vision of American history channelled through a very modern sensibility, in which American ‘roots music’ expressed the concerns of ordinary ‘working people’ and portrayed a range of eccentric ‘colourful’ characters. Tears of Rage tells a similar story to She’s Leaving Home, with similarly tragic results, but here the listener’s sympathy is with the parents rather than the child. The song defines the ‘generation gap’ of the 1960s itself as a tragedy of epic proportions. It has often been noted that Tears of Rage is influenced by Shakespeare’s King Lear, in that it appropriates the impotent voice of a parent railing against his favourite daughter Cordelia’s refusal to ‘butter him up’ by boasting of how much she loves him. But the song is also influenced by Shakespeare in other ways. One of Shakespeare’s most enduring qualities was how he was able to give eloquent voice to characters who are tragically flawed – most notably Othello, Hamlet, Macbeth and King Lear himself. These tragic protagonists are all doomed, but Shakespeare allows us to experience their thoughts and feelings with great intensity, even if most of them are fundamentally unsympathetic characters. Tears of Rage is one of the first Dylan songs which is clearly delivered through the voice of a flawed persona – an approach that he will use in very many songs in the future. Thus, we feel the pain of the parents in the song, even if we may ultimately sympathise more with the daughter.

Both She’s Leaving Home and Tears of Rage have also been interpreted in wider contexts. Their young female protagonists have often been seen as symbolic representations of the rebellion of the younger generation in the 1960s. Tears of Rage has often (like many other Dylan songs), been ‘over interpreted’ to imply that Dylan is making a specific statement about Vietnam or child abuse; neither of which are actually referred to in the song. The lyric merely presents us with a set of parental feelings which we may well apply to particular circumstances but which gain considerable power through their possible generic associations. The opening couplet …We carried you in our arms on Independence Day/ And now you’d throw us all aside and put us on our way… has a particular strong resonance, given that Independence Day has a near-sacred significance in the USA. Here we see the patriotic parents carrying the girl as a baby during the 4th July celebrations. This is presented, however, as a memory. The girl has clearly grown up now and the parents feel that she is treating them with disdain. This was a common complaint at the time as children were growing up with a very different set of morals and expectations to their parents. The theme of ‘independence’ will loom large in the song and it later seems as if the parents resent the level of independence that the child has taken on. A similar play on words is explored in Bruce Springsteen’s 1979 song Independence Day. While the first line resonates as a warm, nostalgic memory, the second – with its succession of curt monosyllables – quite explicitly reveals the bitterness the parents feel.

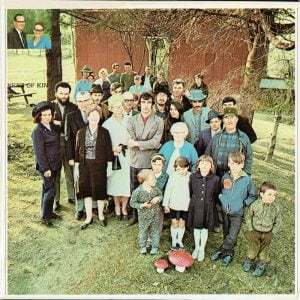

BIG PINK

The following lines take this feeling of bitterness even further …Oh what dear daughter ‘neath the sun could treat a father so/ To wait upon him hand and foot and always answer “no’’… These are the lines that have been especially linked with King Lear. In the first scene of Shakespeare’s tragedy, the foolish old king decides to relinquish his power and divide his kingdom up between his two daughters, wrongly presuming they will look after him. But he then first demands each daughter tell him just how much they love and are devoted to him. The mendacious older sisters Goneril and Regan lay the flattery on thick, but Lear’s favourite and Cordelia refuses to play along with such emotional blackmail. As a result Lear disinherits her, proclaiming:

…Let it be so; thy truth, then, be thy dower:

For, by the sacred radiance of the sun,

The mysteries of Hecate, and the night;

By all the operation of the orbs

From whom we do exist, and cease to be;

Here I disclaim all my paternal care,

Propinquity and property of blood,

And as a stranger to my heart and me

Hold thee, from this, for ever…

As the play is set in pre-Christian Britain, the main religion of the characters appears to be sun worship. Here the daughter is said to be ‘’neath the sun’ – thus under the influence of cosmic forces that may have driven her away from her father’s values. When Lear asks for her protestations of love, she merely replies …Nothing… Lear is mystified …Nothing will come of nothing… he tells her. Several songs on The Basement Tapes, including Too Much of Nothing and Nothing Was Delivered, play around with this concept. Here the daughter merely answers “no” to all their requests. The parents show similar levels of incomprehension.

The chorus, which is repeated three times, is very simple but emotionally gut-wrenching, beginning with the anguish of: …Tears of rage, tears of grief, why must I always be the thief… The father-figure here feels forced into the role of being the ‘bad guy’ (or perhaps the one who ‘stole’ his daughter’s independence). The lines that follow are even more painful: …Come to me now, you know we’re so alone… the father implores in desperation, concluding with …and life is brief… These lines paint a picture of a person in a state of spiritual desolation, already contemplating his own death and the regrets he might feel if he dies without resolving the terrible schism between himself and his daughter. The emotions are expressed here with a particularly brutal realism.

The parents then reveal how their hopes and dreams for their daughter have been dashed. The metaphor used here is simple but extremely effective …We pointed you the way to go and scratched your name in sand… indicates that their attempts to plan her life have failed. But the suggestion here is that their plans never really had a truly solid foundation. Again the next line is particularly scathing …But you just thought it was nothing more than a place for you to stand… There is a distant echo here of the lines in Matthew 7:24:

25 And the rain descended, and the floods came, and the winds blew, and beat upon that house; and it fell not: for it was founded upon a rock.

26 And every one that heareth these sayings of mine, and doeth them not, shall be likened unto a foolish man, which built his house upon the sand…

In comparison to the clear diction on the rest of the song, the next lines are a little convoluted: …I want you to know that while we watched you discover no one would be true/ But I myself was amongst the ones who thought it was just a childish thing to do… It seems that the parents have observed the daughter being betrayed by whoever it is she has followed. The fact that they seem to be condemning her for ‘childish’ behaviour is also rather odd. It is as if we are being presented with snatches of memories which are not contextualised. But what matters in the song is the emotion the parents convey to us, even if it is confused.

The final verse, which ends in one of Dylan’s most resonant metaphors, make the anguish being expressed clearer: …It was all so very painless when you ran out to receive/ All that false instruction which we never could believe… suggests that there may well be a conflict between the apparently conservative and patriotic views of the parents and the ‘false instruction’ the daughter receives. Whether this is some kind of criticism of a liberal education, or whether the girl has joined a group of demonstrators or perhaps even a religious cult, is unclear. But perhaps the most surprising word here is ‘painless’ (not ‘painful’ as one might expect), suggesting that the parents did not have an inkling that this ‘false instruction’ would lead her to rebel against them. Their bitterness is intensified by the feeling that is conveyed here that they have been hoodwinked by her ‘instructors’. The feeling being expressed seems to be very similar to that of many members of the older generation when their children ‘dropped out’, took psychedelic drugs, followed gurus or joined anti-war demonstrations. The final devastating couplet is …And now the heart is filled with gold, as if it was a purse/ But oh, what kind of love is this, that goes from bad to worse?… The parents seem to feel that their hearts are stuffed to bursting with love for her. But the use of the ‘purse’ metaphor suggests that – like the parents in She’s Leaving Home – they have tried to buy her love. Dylan does not have them say ‘my heart’ or ‘our heart’ here but ‘the heart’. The suggestion is that her heart is full of love too, but that has not prevented the estrangement. But as the Prince of Morocco says in The Merchant of Venice …all that glisters is not gold… Even though they claim to be ‘bursting’ with love, the parents may not have understood that, by attempting to deny the daughter her independent life, they have negated that love. It seems, tragically, that they have realised this now, but it is too late.

Tears of Rage is not an easy song to sing. The song conveys more than mere anguish. It also expresses a feeling of impotence in the light of forces that are out of the parents’ control. The song is, as we have seen, open to much interpretation. One can imagine the parents as ‘true blue’ Americans with very conservative values, but this is barely indicated in the lyrics. But by making the lyrics so ambiguous – merely presenting the thoughts of one or two characters without a clear context – Dylan gives the song a universal significance. Many, or perhaps most, parents do at times feel ‘tears of rage’ that their upbringing of their children has not worked out as they expected. Thus, despite its origins as a kind of ‘anti summer of love’ song, it retains its relevance today. But few attempts at the song, by Dylan or others, can be said to match up to the original Basement Tapes versions and the brilliant reading by The Band on their epochal album Music from Big Pink.

Having decided not to release the Basement Tapes material in favour of the sometimes austere, sometimes bizarrely funny ‘stripped down’ song-parables of John Wesley Harding,Dylan gave the song – along with I Shall Be Released and This Wheel’s on Fire – to The Band to release on their first album, on which Tears is the opening track. Big Pink, although it did not record massive sales figures, turned out to be incredibly influential. It was inevitable, perhaps, that the psychedelic era with all its gimmicky associations – would be short lived. For those musicians looking for a new approach, the Band’s first album was a revelation. Eric Clapton was said to have broken up his hugely successful psychedelic blues band Cream after hearing the album, which is full of exquisite songs full of delicately balanced emotions and sometimes surreal lyrics, while simultaneously evoking a kind of dream-vision of a mythic landscape of old Americana. The Beatles themselves – especially George Harrison – were also very impressed and their ‘return to roots’ music on the ‘White Album’ and the Get Back project was directly influenced by the music of Big Pink and John Wesley Harding.

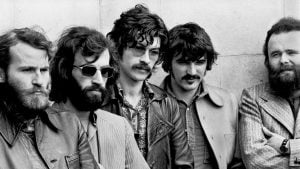

RICHARD MANUEL

Three versions appear on the Bootleg Series release The Basement Tapes Complete. Although Dylan is performing the song for the first time, and the musicians appear to be ‘feeling their way’ around it, the first take is perhaps the most powerful of all, featuring one of Dylan’s most haunting vocals …Listen… Bob mutters quietly. He takes a breath then proceeds to fully inhabit the character he is singing through. There are few occasions in his career where he is so successful at acting his way through a song. Rick Danko’s bass is prominent in the background. There are no drums as Levon Helm was still absent from the sessions. There is some slight distortion in the sound, but this only adds to the immense poignancy of the performance. The song ends just seconds after the last chorus. As he reaches the climactic image Dylan’s voice soars as he explores the metaphor of the purse being full of gold as a heart full of love. The performance is a perfect balance of the emotions of pain, regret and grief, balanced somehow by an inkling of hope. The second take is slower, but cuts out after two verses. The eerie backing vocals, supplied by Richard Manuel and Rick Danko, become more prominent. This approach is extended in the third version (which was released on the 1975 official album) in which Dylan’s passionate and fully committed vocal is enhanced particular by Manuel’s gorgeous falsetto on the choruses. Now it is as if both mother and father and singing together. As the song progresses both Manuel and Danko improvise wordless atmospheric sounds, which add greatly to the way the song builds up to its enigmatic climax.

The version of Tears on Big Pink has some slight lyrical differences and verse two and three are reversed. The Band possessed three very distinctive singers in Levon Helm, Rick Danko and Richard Manuel. Manuel, who wrote the music for the song after Dylan presented him with a sheet of lyrics, produces a stunning vocal performance, with his plaintive high vocals fully expressing the song’s tortured emotions. The song became a prominent feature of The Band’s live shows but few of their versions matched the intensity Manuel demonstrates here. Rick Danko’s backing vocals, which are in a slightly lower register than Manuel’s, are clearly distinguishable, adding that ‘extra verse’ to the song. Helm’s drums are precise and restrained, as are Robertson’s guitar licks. As in Dylan’s original version, Garth Hudson’s swirling organ adds considerable suspense and mystery. These recordings were very much the product of a particular time, place and attitude. Although Dylan has played the song over 90 times in the course of the Never Ending Tour, few of the later live versions really match up to the intensity of the original recordings. A recording made during the rehearsals for the Rolling Thunder Tour in 1975 features dual harmonies by Dylan and Joan Baez, but it peters out before the end and the song was not played on the tour. It seems that the musical chemistry between Dylan and The Band – and between Dylan and Manuel in particular -was essential to conveying the delicate balance of feelings that the song conveys. Having introduced political protest and symbolist poetry into popular music, Dylan and The Band now present another startlingly new innovation – the popular song as a dramatic soliloquy – which is only truly effective when presented as a feature of the wholly original, subtle and strikingly emotive musical alchemy that these musicians created together.

DAILY DYLAN NEWS at the wonderful EXPECTING RAIN

THE BOB DYLAN PROJECT- COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

Leave a Reply