After the apocalyptic thunder subsides, a soft, jazzy shuffle takes us back to the beginning of all things:

In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. Now the earth was formless and empty. Darkness was on the surface of the deep. God’s Spirit was hovering over the surface of the waters. God said, “Let there be light,” and there was light. (Genesis 1:1)

The voice is the tender whisper of an ageing crooner. The music rolls in a steady tempo, with deep, subdued double bass, delicate brushes on the drums, gently tinkling piano and tasteful snatches of violin and guitar. As he lures us into the song, it is as if the singer’s spirit is indeed hovering over on the surface of the primordial ocean, gliding in air in the moment before creation. His heart, it seems, is light. He is in love, besotted with some young Princess or other. He can hardly sleep. …You got a face that begs for love… he coos. Yet it’s clearly him who’s doing the begging. He trembles with anticipation as he looks forward to the moment of a great awakening. He is ready to confess his deep devotion, to express his humility and to give thanks for the sheer privilege of being allowed merely to stand in the presence of his beloved. Hers is the spirit that moves upon the face of the water. His is the darkness. He is down on his knees now, as if in prayer. And he is ready to confess…

Of course, he doesn’t have a hope in hell with her. The Princess will wrap him round her little finger. Yet he seems to revel in every moment. He wants us to believe that he …can’t explain/the sources of this hidden pain… But we know better. He takes on the traditional role of the self-effacing, martyred lover: …If I can’t have you… he breathes … I’ll throw my love into the deep blue sea… He wants to allow us to share in his heartbreak, to experience the bittersweet taste of his tragic disappointment. Like a true romantic fool he tells her …life without you/doesn’t mean a thing to me… But we can only begin to pity him as the evidence accumulates that she is using him: …You do good all day/You do wrong all night… We can almost see the tears of joy, mingled with traces of his ‘hidden pain’. The lines …When you’re with me/I’m a thousand times happier than I could say… are delivered with cute nonchalance, as is the following …What does it matter/What price I pay?… Although the singer may wish to dismiss his own suffering, trying to make us believe that just spending some time in her presence makes the humiliation he must face bearable, but the lightness of his tone betrays him.

Up to this point, the language of the song is a kind of understated plainspeak. But now the singer begins to throw out more imagistic phrases that take us into more mysterious realms. Much of MODERN TIMES is steeped in the nuances of the language of the blues, with its sly sexual innuendos. Here the singer implores his love to …put some sugar in my bowl/I feel like lying down… The plea is a straightforward come-on but the cool, resigned delivery of the lines conjures up a world-weariness that suggests that a ‘lie down’ is really all he needs. Certainly, it’s all he’s likely to get. The next lines are the most remarkable and moving in the song, as the singer’s self-effacement has him picturing himself fading away, the substance of his body becoming like mist and shadow. …I’m as pale as a ghost… he sighs …holding a blossom on a stem…. Not a ‘flower’, mind. What he offers her is something incomplete, faded, barely even visible. Though he tells her that he …can’t believe these things could ever fade from your mind… we can be pretty sure that they will. His pleas become increasingly hopeless. He tells her he will accept any humiliation to be with her, and begins to dream of a kind of eternal union which might extend even beyond the grave. Yet the strange confession in the penultimate verse, that he cannot join her in ‘paradise’ because …I killed a man back there… (With its odd echo of Johnny Cash’s line in Folsom Prison Blues: …I shot a man in Reno/just to watch him die…) suggests that he considers himself – as a miserable sinner – unworthy of her. He ends jauntily, suggesting that, even without this ‘paradisiacal’ union, they could still …have a whomping’ good time… together. But Paradise has been lost. Together they could have had their own moment of creation, with her spirit moving over his ‘dark waters’ to create a flash of blinding, inspirational light. However, it is not to be.

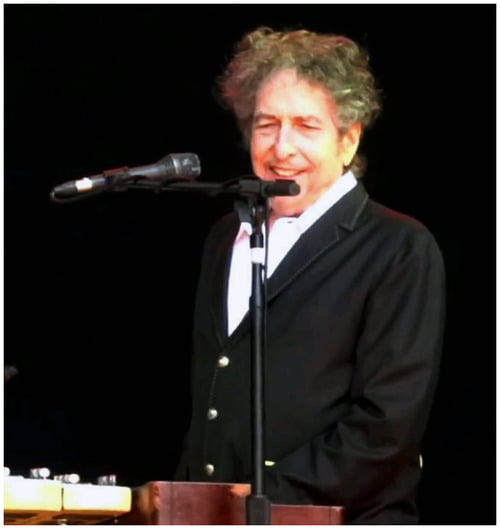

The songs on MODERN TIMES are, like so many of the great blues songs, sung by what the literati like to call ‘unreliable narrators’. We have to ‘read through the lines’ of what they so convincingly profess to see what is really going on. As with songs like Moonlight and Bye and Bye on LOVE AND THEFT, Dylan’s adoption of the ‘easy crooning’ style in Spirit on the Water (and later on in the even more arch Beyond the Horizon) is a kind of subterfuge. He appears to be embracing the sentimental style of 30s crooners like Bing Crosby in order to cast himself in the role of an ageing roué. Like the ‘Southern Gentleman’ look he has appropriated for his live performances, this is another ‘Dylan mask’…

And so, on LOVE AND THEFT and MODERN TIMES Dylan feels free to play with the form of the love song again. On LOVE AND THEFT’s Mississippi he uses the geography of America as a kind of metaphor for a failed relationship. Or maybe, just maybe, it’s the other way round. In the epochal Sugar Baby he appears to be bidding a cracked farewell to love itself: … You spent years without me.. Might as well keep going now … Now, on MODERN TIMES – an album which, in its own way, is as preoccupied with love as TIME OUT OF MIND, BLOOD ON THE TRACKS or NASHVILLE SKYLINE, he steps behind a series of disguises. He becomes a kind of ‘ghostly’ figure in the background of the songs’ shifting personas. Spirit on the Water epitomises this new approach. The flower of his youth may have faded but he is still holding that fragile blossom on a stem, dreaming of eternal bliss, with a fair measure of lust thrown in for good measure. The song seems to literally float past us and Dylan brings a new assurance and confidence to his use of the conventions of the ‘romantic’ song. Behind each sighing gasp of romantic despair there is a touch of ironic lightness, a sense that whatever tearful protestations he may be presenting us with, the singer has in reality been liberated from the ‘hidden pain’ that love brings. It is hard not to read the final lines as a message to his audience that he’s not ‘over the hill’ just yet.

But with Dylan, as ever, little is what it seems at first. In many ways the playful spirit of MODERN TIMES harks back to Dylan’s mid-60s masterpiece BLONDE ON BLONDE, a series of sly, trickily worded songs which (on the surface) were each addressed to different women, from the tragic lovechild of Just Like A Woman to the girl to whom he was Pledging My Time, to the shifting eternal female-symbol of Sad Eyed Lady Of The Lowlands. Hovering behind them all is the figure of Johanna, the mysteriously fading …ghost of electricity… All these women are, on one level, aspects of B.O.B. himself. Dylan uses the forms of the ‘female principle’ – the ‘visions’ which ‘conquer his mind’ to reflect on both universal and personal dilemmas and to counter pose symbolic elemental forces within himself. Like the ubiquitous Johanna, the actual subject of Spirit On The Water is entirely absent from the song. She is not a ‘real woman’ but a symbol of creativity itself, a ‘Johanna’ for ‘Modern Times’. The song is a kind of address to his own inner creative spirit, without which life ‘doesn’t mean a thing’. Of course, there is a ‘price to pay’ for such devotion – the individual who surrenders his life to creativity can become like a fading ghost (just like Johanna again). But here, just as he once luxuriated in the fabulous image of the ‘ghost of electricity’, Dylan pictures himself as a ghost, the ghost of one who has surrendered all his emotional substance to the creative process. And he revels in the freedom his new role brings – unencumbered by physical form he can dance lightly – walking, perhaps on water – yet freed from desperate lust, freed from the agony of spiritual searching. It has been a long, tortuous journey – many times he has laboured in the slough of despond, trying to convince himself he’d ‘found Jesus’, evoking the spirit of a dead bluesman on the discarded Blind Willie McTell, then caught in the despair of ‘inspiration fatigue’ of the late ‘80s where he thought he’d have to quit because the ‘spirit’ of creativity was no longer with him. He has had to reach back, not only into a poetic-mythical pre-war ‘weird America’ and the ‘roots’ of the blues but also into the deepest depths of his soul. Now, having grown into a new persona – the ghostly figure, perhaps of some Civil War poet that you might have in some old painting on your mantelpiece – he can again be as playful as he was in his halcyon days when the spirit would descend upon him and visionary songs would pour out of him as if they were already written, dictated to him by ‘the powers above’. Thus Spirit On The Water is a kind of autobiographical song, a manifesto for the album, and perhaps for the rest of Dylan’s career. With the calmness of experience, the wisdom of age, he has finally learned – or to be more precise, re-learned – a way in which the spirit of creativity can be allowed to move through him so that he can speak the words that bring him – and us – into the light. He was so much older then… he’s younger than that now…

A different version of this text appears in DETERMINED TO STAND: THE REINVENTION OF BOB DYLAN

————————————————————————————————————————————————-

DYLAN LINKS

DAILY DYLAN NEWS at the wonderful EXPECTING RAIN

THE BOB DYLAN PROJECT- COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

THE CAMBRIDGE BOB DYLAN SOCIETY

Leave a Reply