| 1 |

Hi folks… DETERMINED TO STAND: The Reinvention of Bob Dylan is now available HERE

Here are some extracts from the book…..

DARK EYES

4th December 1995. The Beacon Theater, New York City. It is the sixth date of the short ‘Paradise Lost’ tour, on which Dylan is supported by Patti Smith and her band. We are at the end of the acoustic section of the gig, and Dylan – accompanied by John Jackson on guitar – has just played stark and intimate versions of Mr. Tambourine Man, Masters of War and Mama You Been on My Mind. Quite a treat for the fans. But an even more special moment is about to occur …Mmm… I’d like to ask Patti to sing a song with me…. Bob mumbles. And there she is, in a long red dress, her dark hair shaken loose, looking like a shamanic priestess. As she sings she raises her hands to her face and closes her eyes: …Oh, the gentlemen are talking, and the midnight moon is on the riverside/ They’re drinking up and walking and it is time for me to slide… You can tell that she is absolutely cherishing every word, and that as a poet herself she is being transported by delight to be conveying these sparkling, magical images.

Dark Eyes is one of the great hidden gems in Dylan’s catalogue. Tucked away on the end of one of his most hit-and-miss 1980s albums Empire Burlesque, and apparently written ‘off the cuff’ in the studio, this is a song that appears to have come to Dylan entire, in a vision (much like songs like Mr. Tambourine Man or It’s Alright Ma had back in the ‘60s) in the middle of a period when he was struggling for inspiration. The studio version, a brief solo acoustic number, is in stark contrast to the rest of the album, with its rather overblown 80s production. Tonight’s rendition, with Smith taking the first two lines of every verse and Dylan joining in with the last two, takes the song to new heights.

The song is a dream-vision reminiscent of the greatest work of the romantic poets. It has four verses and no choruses and each verse ends with the title. It takes us quite explicitly into a fantasia of the poetic imagination: …I live in another world… Bob and Patti sing together…where life and death are memorised… It is as if all creation is passing before him. Being able to picture this is the gift of the true visionary. But it is not, as we will soon hear, an easy one to bear. This line is followed by one of staggering radiance: …Where the earth is strung with lover’s pearls and all I see are dark eyes… ‘Lover’s pearls’ is simultaneously an image of purity and sexual intimacy – the ‘pearls’ being both manifestations of immeasurable beauty and drops of glistening semen, ready to fertilise the world. Not this world or heaven or hell – but the world of the poetic imagination…

Patti’s voice is soaring and pure but quavering in wonder. Bob’s is harsher, darker. It seems that there is something he knows about this ‘other world’. The luminescent images keep coming: …A cock is crowing far away and another soldier’s deep in prayer… Patti sings. Then …Some mother’s child has gone astray, she can’t find him anywhere… It is as if she is channelling the voice of Blake, summoning up an emanation of his poetic spirit. The little boy is lost. A mother wails. Then Dylan joins her for the apocalyptic lines: … I hear another drum beating for the dead that rise/ Whom nature’s beast fears as they come, and all I see are dark eyes…. The day of judgement is at hand. The ‘beast’ of Revelations is about to manifest itself, in fear of the rising dead. The contrasts in the song are extreme – from absolute beauty and perfection to utter terror and destruction. In this ‘other world’ the poet sees it all. Dylan muses on how painful it can be to be privy to these visions, for others can never see what he sees. These ‘others’ mock him and abuse him …They tell me to be discreet for all intended purposes/ They tell me revenge is sweet, and from where they stand I’m sure it is…. But he is determined not to flinch: …But I feel nothing for their game/ Where beauty goes unrecognised… As a poetic ‘seer’ he must bear the pain – or perhaps the awful numbness – of living in a world in which such visionary ‘seeing’ is dismissed, perhaps as madness. It is as if he is experiencing hell itself: …All I feel is heat and flame/ And all I see are dark eyes….

The final verse throws a series of astonishing ‘jump cuts’ at us …Now the French girl, she’s in Paradise and a drunken man is at the wheel… The French Girl is a song by Ian Tyson about a beautiful but enigmatic muse. Dylan recorded an impassioned version for The Basement Tapes. The phrase also conjures up an image of Joan of Arc – a visionary who was labelled as being mad – being consumed by the ‘heat and flame’ as she is martyred. Because of her faith, she can feel no pain. She is already in paradise. Meanwhile, a ‘drunken man’ is in charge of a world spinning out of control …Hunger pays a heavy price to the falling gods of speed and steel… uses a powerful double alliteration in another apocalyptic clash of images, as the industrial world is consumed in the flames. Finally the bow of Cupid, the Ancient Roman god of love, is stretched out to express his perception of how fleeting the joys of life are …Oh, time is short and the days are sweet and passion rules the arrow that flies… Then, in a haunting denouement, he summons up the burden of the visionary …A million faces at my feet, and all I see is dark eyes… The poet with a huge international audience ‘at his feet’ stares into the multitudes but those ‘dark eyes’ – those precursors of disaster, of failure, of death – are inescapable. Whatever success we have been achieved in the material world, and even as that world crashes around us, those eyes, which Blake called …this life’s dim windows of the soul… will continue to watch us. It is thus crucial, given one’s brief sojourn on earth, to make sure that each one of those ‘sweet days’ is savored. One must engage with the ‘passion’ that lifts the experience of those days to another level during the swift ‘arrow flight’ of our lives. The job of the poet, therefore, is to use this ‘passion’ to leap into the ‘other world’ of the imagination – to make a futile but heroic attempt at achieving immortality – to step outside of time…

ROLL ON JOHN

In Roll on John, the concluding track on Tempest, the murder that is central to the narrative is never described. Yet that murder is one of the most tragic results of the USA’s ‘gun culture’. The song is an elegiac tribute to John Lennon which ‘rolls’ its anguished but celebratory message over a stately melody. Dylan was reported to have taken the custodians of the ‘Liverpool Beatles industry’ by surprise in 2009 by appearing unannounced on a tour of Lennon’s childhood home in Menlove Avenue. It may well be that the song was written around this time. Dylan and Lennon were not, however, close personal friends. They never collaborated musically, and met each other on just a handful of occasions. The mutual influence of Dylan on The Beatles and vice versa has, however, long been acknowledged. Dylan prompted them to write more imaginative, poetic lyrics, while their success encouraged him to play with an ‘electric’ band. This confluence had a huge effect on the rapid explosion and development of rock music in the 1960s. Here Dylan presents an impressionistic view of Lennon’s life, depicting him as a flawed human being who nevertheless displayed distinctly heroic qualities. It is undoubtedly a heartfelt tribute, not to Lennon as a friend but as a cultural icon.

As John Lennon began to write more personal, meaningful songs it became obvious that he was struggling with many personal demons. In one of his most profound works, Strawberry Fields Forever, he relives aspects of his troubled childhood against a backdrop of complex and innovative psychedelic music. In the late 1960s and early 70s, as The Beatles were breaking up, and he was conducting a very public relationship with the Japanese-American conceptual artist Yoko Ono, he worked out many of his own psychological problems through his songs. This was especially true on the stark and sometimes brutally honest post-Beatles album John Lennon/ Plastic Ono Band (1970). He later relocated to New York City and took up residence with Ono in the Dakota Building, where he remained until his murder by a crazed fan in 1980. For five years he abandoned public performance and recording, living life as a ‘house husband’ while Yoko took care of business.

Lennon had courted notoriety in many ways, especially in his often forthright public pronouncements. The most notorious of these, his assertion that The Beatles were ‘bigger than Jesus’ in Britain, was – though taken out of context – the stimulus for him to be publicly vilified in the USA, when elements of the religious right organised mass burnings of Beatles records and memorabilia. On their final tour of America in 1966 he and the other Beatles were genuinely afraid that they might be killed. They had already incurred death threats by upsetting religious sensibilities in Japan when they played the Budokan, a sacred martial arts temple. In the Philippines the army had chased them out of their country following a perceived snub to the First Lady, Imelda Marcos. They then abandoned their extensive tours, in which their music was largely being drowned out by hysterical screaming fans. Lennon’s assassin Mark Chapman later pronounced that the ‘Bigger than Jesus’ statement was one of the reasons he shot him. Lennon’s life was thus both heroic and tragic. On the one hand he was seen as a kind of prophet. His most famous solo song Imagine asked the listener to conjure up a world without war, hatred and religious dogmatism. On the other hand, his personal problems and his wayward behaviour – about which he was often disarmingly honest – plagued him throughout his life.

Roll On John examines both sides of Lennon, recasting him as a modern flawed hero in the mould of Homer’s Odysseus and portraying his life as a turbulent ‘journey’ through stormy seas. Each of its eight verses culminate with the ‘anthemic’ chorus …Shine your light/ Move it on/ You burned so bright/ Roll on John… The song begins: …Doctor, doctor, tell me the time of day/ Another bottle’s empty, another penny’s spent… Dylan’s vocal here is especially harsh. At various times in his career Lennon was known for his heavy indulgence in drink and drugs. Now, it seems, we are catching him during his ‘lost weekend’ of 1974, when he had temporarily split from Yoko Ono and was ‘hanging out’ in Los Angeles with self-destructive ‘party animal’ rock stars like Keith Moon and Harry Nilsson. He is depicted here as being in an alcoholic delirium. The lyrics refer to the English expression ‘to spend a penny’, meaning to urinate. We can picture Lennon staggering through the streets with his pals, pausing to piss against the nearest wall. Hardly the most ‘heroic’ of openings, but indicative of the depths the subject of the song could sometimes descend to.

Then we hear that …He turned around and he slowly walked away…. After these indulgences, Lennon returned to Yoko and became a devoted father. But the scene being described here could also show him giving his autograph to a fan, turning around and walking towards the doors of the Dakota building, as if we are now watching his last moments in slow motion. This was a place where fans often besieged him. Earlier in that day, one of those autograph hunters (for whom Lennon signed an album cover) had been Mark Chapman. We hear that …They shot him in the back and down he went… There is no mention of any individual assassin – just the generic ‘they’. Perhaps Dylan is asserting that Lennon’s killer could have been any one of those crazed Americans who had somehow assumed that Lennon was trying to deify himself and would therefore have to be eliminated. In one of his last songs for The Beatles, The Ballad of John and Yoko, Lennon recounts details of his and Ono’s public ’demonstrations for peace’ such as their week long ‘bed-in’ in an Amsterdam hotel where they recorded his optimistic ‘anthem to the world’ Give Peace a Chance. But The Ballad is a deeply cynical song. After complaining about his vilification by the press, its chorus drily observes: …The way things are going/ They’re gonna crucify me… This was a sarcastic reference to the way the media had blown his ‘bigger than Jesus’ comment out of proportion. In his choice of pronouns, Dylan echoes Lennon’s statement. ‘They’ have killed him, thus implying that his ‘crucifixion’ has at last come to pass.

The next verse takes us back in time to Lennon’s youth and the Beatles’ early engagements: …From the Liverpool docks to the red light Hamburg streets… In the next line we are …Down in the quarry with the Quarrymen… The implication seems to be that Lennon’s rise to fame came out of great hardship and social deprivation, although this is a considerable exaggeration. Dylan correctly name checks ‘the Quarrymen’ as Lennon’s pre-Beatles group. But he is surely having a little joke on us here, as we can hardly be expected to believe that he thinks Lennon ever worked in a quarry. This is followed by another affectionate light hearted jest: …Playing to the big crowds, playing to the cheap seats… refers not only to the Beatles’ stadium gigs in the US between 1964 and 1966 but also to Lennon’s quip at the 1963 Royal Variety Performance in London (in the ‘presence’ of the Queen Mother) that …those of you in the cheap seats can clap your hands. The rest of you can rattle your jewellery… Despite having accepted manager Brian Epstein’s proviso that they swap their Hamburg leathers and quiffs for smart ‘Beatle suits’ and uniform haircuts, Lennon hated having to fawn to royalty and wound up Epstein by telling him that that his introduction to Twist and Shout would include the words …rattle your fucking jewellery… As it was, he carried off the introduction with a cheeky grin, much to Epstein’s relief.

Roll on John is unstinting in its portrayal of Lennon as a troubled soul who is engaged in a difficult, if not impossible, journey through life that seemed destined to end tragically: …Another day in the life on your way to your journey’s end…. Dylan sings, referencing The Beatles’ A Day in the Life, which begins with a senseless death and ends with a vast cataclysm of noise. Lennon told producer George Martin that they wanted ‘a sound like the end of the world’. But Dylan carries the line off with touchingly sympathetic sadness, as if that monumental track was indeed a metaphor for Lennon’s own tragic life. Lennon was drawn towards celebrity by his inexorable desire for wealth and fame but even when he achieved this, after the whirlwind of sex, drink, drugs, meditation and therapy he put himself through, he still often felt – as one of his later songs put it – ‘crippled inside’.

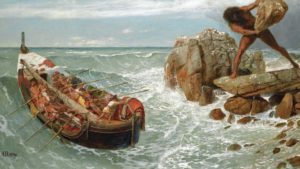

From here we shift in time and space as Dylan identifies Lennon with the great mythic heroic figure of Odysseus, linking his struggles to the Greek hero’s battles with supernatural beings. He begins to interject lines that he has taken directly from Robert Fagle’s translation of Homer’s Odyssey (1996), such as …Sailing through the trade winds, bound for the south/ Rags on his back like any other slave… During his journey, Odysseus is trapped for several years by the nymph Calypso, who wishes to make him immortal and so forces him to become her lover. Despite achieving the kind of worldwide fame that ensured his ‘immortality’, Lennon still felt trapped and ‘enslaved’ by the pressure to conform to his image as a ‘loveable mop top’. In the early years of his fame, he had to hide his true personality behind his image as the cheeky, slightly cynical Beatle. This meant that he was unable to express his political or personal opinions. …They tied your hands and they clamped your mouth… Dylan sings …wasn’t no way out of that deep dark cave… Having set up Lennon as a ‘mythical hero’, his troubles are compared to those of Odysseus. In the Odyssey the hero is trapped in a cave by the one-eyed Cyclops Polythemus, who eats several of his men, but Odysseus is cunning enough to trick his way out. Lennon did indeed escape from the ‘trap’ that The Beatles were in. After renouncing touring they spent most of the next few years in the studio creating masterpieces like Sgt. Pepper, The ‘White Album’ and Abbey Road.

The next verse is concerned with the public reaction to Lennon’s death. Since taking up residence in New York, he had become something of a ‘local hero’. He would stroll around the city alone, without a disguise or a bodyguard. The first line …I read the news today, Oh boy… quotes the haunting opening of A Day in the Life and applies it to the news of Lennon’s murder. In the next line Lennon is again the trapped Homeric hero: …They hauled your ship up on the shore… is another line from Fagles’ translation. And then, with a voice that has now softened considerably, Dylan intones, in the song’s saddest lines …Now the city gone dark, there is no more joy/ They tore the heart right out and cut him to the core… After Lennon’s murder, devastated fans kept vigil outside the Dakota for several days. As the world mourned a lost hero, it seemed that the ‘heart’ of the city – in which Lennon had, perhaps naively, trusted the people – had been torn out. A section of Central Park was later named ‘Strawberry Fields’ in his honour.

In the next three verses, which are mainly focused on Lennon’s final years, Dylan appears to travel back through time to speak to Lennon directly, as if he is giving him helpful advice which we know he will never listen to: …Put down your bags and get ‘em packed/ Leave right now, you won’t be far from wrong… Dylan advises …The sooner you go, the quicker you’ll be back/ You’ve been cooped up on an island far too long… The fourth line here is another direct quotation from The Odyssey, referring to Odysseus’ entrapment by Calypso. The earlier lines refer to Lennon’s stated desire, after his years being ‘cooped up’ in the Dakota, to revisit his native island (Britain) again; an ambition which he sadly never achieved. Lennon had been afraid to leave the USA in case he was not allowed back in the country, due to a minor marijuana bust he had suffered in London in 1968. The narrator now appears to be imploring Lennon to take that journey, which might have meant he would have avoided being murdered. Despite the fact that by 1980 he was again making new music – his album with Yoko, Double Fantasy had just been released – he never travelled the world on his own ‘Never Ending Tour’. He never reunited with The Beatles to head up Live Aid in 1985. Like so many mythical heroes, he never grew old. Perhaps the most moving moment in the Live Aid show was a stripped down, solo acoustic rendition of All You Need Is Love, performed by an impassioned Elvis Costello, who seemed to be channelling Lennon’s ghost, which somehow appeared to be hovering over the whole event. Costello prefaced his performance by telling the crowd: …I’d like to sing an old Liverpool folk song…

In the sixth verse Dylan quotes from three songs performed by Lennon …Slow down, you’re moving way too fast… paraphrases the Larry Williams number that The Beatles recorded a sparkling cover of in 1964 …Come together right now, over me… quotes directly from 1969’s Come Together, Lennon’s rather surreal appeal to members of ‘the underground’ to be more focused in their drive for ‘revolution’. These lines also function as sadly futile attempts at persuading Lennon to take a different path. But the third line …Your bones are weary, you’re about to breathe your last… takes us forward to Lennon’s final moments …Lord, you know how hard that can be… is lifted directly from The Ballad of John and Yoko.

ODYSSEUS

This is followed by another rather strange diversion: …Roll on John, through the rain and snow/ Take the right hand road and go where the buffalo roam… The first line’s depiction of adversity recalls the cry of the despairing, long-suffering lover in the Grateful Dead’s Cold Rain and Snow. The second echoes Walt Whitman’s Song of The Open Road, which looks philosophically at life’s choices …The earth expanding right hand and left hand/ The picture alive, every part in its best light… as well as the famous ‘cowboy ballad’ Home on the Range (which begins …Oh give me a home where the buffalo roam…) which Dylan later insisted, in his Nobel Prize Lecture of 2017, was ‘influenced’ by Homer’s Odyssey. This is presumably because the Odyssey is focused on a long and difficult journey to an idealised home. Here Dylan, having previously advised Lennon to ‘slow down’, appears to approve of his decision to ‘stay home’ with Yoko for several years in the late ‘70s. He himself had experienced a similar period of domesticity a few years before. Still addressing Lennon as Odysseus, he warns that …They’ll trap you in an ambush before you know/ Too late now to sail back home… but of course the warning will be futile.

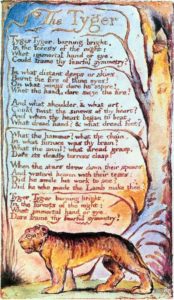

The concluding verse carries Dylan’s tribute to an exultant, even ecstatic, conclusion. Interweaving lines from William Blake’s The Tyger with those of a nursery rhyme, he bids farewell and makes a final tribute. Blake was, of course, like Lennon and Dylan, a poetic songwriter. It is said that he would publicly perform his songs, some of which were later set to music by Hubert Parry (the composer of the music to Jerusalem, the ‘unofficial’ English national anthem), Ralph Vaughan Williams, Allen Ginsberg and many others. The Tyger, which is certainly one of the most powerful poems in the English language, eulogises the magnificent if fearsome beast in a celebration of life energy, blending beauty and danger in unforgettable couplets, encapsulating both the heroic promise of liberation of the French Revolution and its destructive force. By using such a well-known allusion, Dylan celebrates Lennon’s irrepressible energy – as a fellow musician and poetic lyricist and indeed as an outspoken revolutionary – while showing us where his journey into those ‘dark forests’ led him …Tyger, tyger, burning bright… Dylan sings, contrasting this with …I pray the Lord my soul to keep… from the nursery rhyme. He celebrates the energy-force of both Blake’s ‘Tyger’ and Lennon and prays that he be allowed to channel some of that force – the spiritual power of inspiration and the imagination – himself.

The final lines are immensely touching in their quiet humility: …In the forest of the night… is taken directly from The Tyger. This is followed by …Cover him over and let him sleep… as if ‘little John’ has been ‘reborn’ as an innocent child – recalling the climactic birth of the ‘Star Child’ at the end of the ‘psychedelic sequence’ of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001- A Space Odyssey. When Lennon saw this film he is said to have declared that a temple should be built in which it should be shown on a continual 24 hour loop. By means of this prayer, Dylan identifies his own poetic spirit with both Lennon and Blake. ‘Experience’ and ‘innocence’, which Blake called ‘the two contrary states of the human soul’ are now reunited. This is the same tortured soul who once uttered the ultimate cry of anguish in one of his songs: ….Mother, you had me, but I didn’t have you/ I wanted you, but you didn’t want me… The ‘star child’ ‘John’ (the most common English name and sometimes used as a euphemism for ‘the average man’) is thus returned to innocence and, despite the pain he has suffered in his life, has now achieved a kind of immortality, by creating songs that will (in the words of Lennon’s ultimate acolyte Noel Gallagher) ‘live forever’).

If any one song can be said to justify Dylan’s recurrent use of allusion – of ‘lifting’ the words of other writers – which is such a prominent feature of his ‘late style’, this is it. Despite the apparent obscurity of some of its lines, it is very carefully crafted, with each quotation from Lennon reflecting on aspects of his life. The allusions to Blake in the last verse work as a perfect summary of the qualities of Lennon as a ‘heroic’ figure in the classical sense – one who, like Odysseus, has to confront a life of struggle against apparently insuperable difficulties. The song-chorus verse structure has a simple repeated ABAB rhyme scheme, but it is only in the last verse that the first two lines ‘bright’ and ‘night’ rhyme with the final corresponding lines in the chorus – ‘light’ and the repeated ‘bright’, emphasising how John’s light will keep burning eternally. It is as if the chorus has been ‘waiting’ for this final verse. Roll On John is a deeply sincere tribute to perhaps the only person in rock music history who can be said to rival Dylan as its most influential figure. It is also a kind of secular prayer – a paean to an artist who was decidedly not – as The Ballad of John and Yoko makes clear – any kind of ‘Jesus figure’. He certainly did not want to be ‘crucified’, but he was brave enough to expose his own inner turmoil and suffering to the world in the most unequivocal terms.

DYLAN LINKS

DAILY DYLAN NEWS at the wonderful EXPECTING RAIN

THE BOB DYLAN PROJECT- COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

THE CAMBRIDGE BOB DYLAN SOCIETY

Leave a Reply