Caribbean Wind,

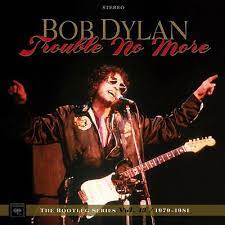

which was written in late 1980, remains something of an enigma in Bob Dylan’s career. Although it is a song which Dylan regarded as ‘unfinished’, it has often been acclaimed as one of his most luminous creations. When it first reached a wide public on the 1985 compilation Biograph, many listeners were surprised that this powerful, emotive and mysterious work had been omitted from 1981’s Shot of Love. Two more versions (one a rehearsal, the other its sole live outing) were later released on the Bootleg Series’ Trouble No More. An earlier studio outtake, which has circulated as an unreleased recording, also exists. There are thus four extant versions, all of which differ significantly in terms of lyrics and music. Dylan fans are generally divided over which is their favourite. Caribbean Wind can thus be viewed as four different songs – or four takes on the same song – each of which has its own particular qualities. Fans and commentators have widely differing opinions on which of the four is the best.

One of Bob Dylan’s most significant contributions to the art of poetic song writing is his presentation of ‘variant’ versions of his compositions. In live performance, rehearsals and in the studio he has frequently been known to adjust both his lyrics and his musical arrangements. Sometimes audiences at his live shows even fail to recognise particular songs, at least until a familiar chorus appears. Such fluidity is very much a part of the country blues tradition. The work of those artists who originally forged the lyrical and musical features of the blues – usually solo artists accompanying themselves on guitar – has often been misread as ‘primitive’. Yet innovators such as Charley Patton, Blind Willie McTell, the Rev. Gary Davis and Robert Johnson were all artists who relied mainly on live performance to make a living. At each show they had to judge the type of crowd they were playing to. Thus they learned to modify their songs and adapt the compositions of others in a wide range of locations, such as dance halls, concert halls or street performances. Verses, melodies and musical and lyrical twists were often applied to songs with which the audience were already familiar, but now with the added stylistic inflexions of individual performers. Dylan’s work is thoroughly grounded in this ethos.

Caribbean Wind

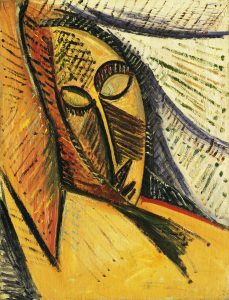

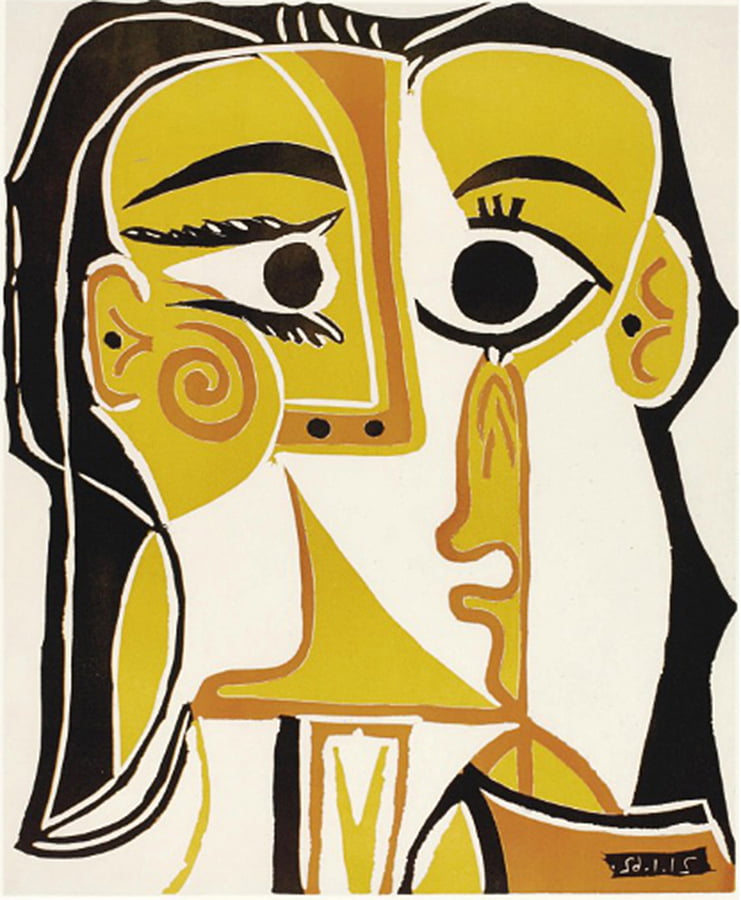

The years in which these blues styles were honed – from the 1910s to the 1940s – were also those in which the stylistic tropes of modern art rose to prominence. In Picasso’s paintings a scene often appeared to be viewed from several angles at once, creating a feeling of ambiguity and the sense that each piece could not necessarily be attached to one particular ‘meaning’. In the mid 1970s Dylan’s attendance at the art classes of Norman Raeburn influenced his creation of ‘cubist’ songs like Tangled Up in Blue, Idiot Wind, Black Diamond Bay and Changing of the Guards, with their patterns of scene shifting and use of ‘sliding’ pronouns. These techniques allowed the listener to experience the stories Dylan was relating from different perspectives simultaneously. Perhaps the most extreme example is Tangled Up in Blue, which has been performed in a plethora of lyrical and musical styles over the years, with whole verses and individual lines being replaced.

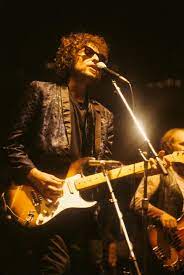

Caribbean Wind is especially popular because of its winning melody, its attractive and memorable chorus and its mysteriously enigmatic lyrics. This was particularly striking because it was composed at a time when Dylan had just released Slow Train Coming and Saved – two albums of gospel songs with direct and unequivocal Christian messages. In his tours of 1979 and 1980 Dylan had played only his religious material, often with fiery intensity, in some of the most powerful performances of his career. But by the time of his final tour of 1980, older ‘classics’ like Like a Rolling Stone and Girl from the North Country were being reintroduced into his sets; a pattern which continued in his concerts of 1981. Although the shows were preceded by gospel songs performed by his backing singers, Dylan no longer launched into ‘religious rants’ on stage. There was a sense in which the initial fervour of his conversion was dimming.

The song is a kind of bridge between Dylan’s ‘born again’ period and the years of doubt and uncertainty which followed. It is centred on memories of a relationship, presented as a kind of dream-vision, in which he begins to question the morality and beliefs he had ingested and expressed with such apparent fanaticism after his ‘vision of Jesus’. It provides no obvious answers or solutions to his spiritual predicament. But Dylan presents us with many images that reflect somewhat ruefully on the experience he has been through.

The four renderings of the song all conform to the same basic structure, with six verses of six lines each, all with an AABCCB rhyme scheme. The choruses consist of four lines, with rhymes at the end of the second and fourth lines and internal rhymes in lines one and three. The first known version (recorded at Rundown Studios on 23rd September 1980 and popularly known as the ‘pedal steel’ version) is relatively slow and reflective, with a richly ruminative vocal. The second, somewhat livelier, take is the sole live performance of the song, recorded at the Fox Warfield Theater in San Francisco on 12th November 1980. The rendition is preceded by a rather rambling introduction:

…This is a 12-string guitar. First time I heard a 12 string guitar was played by Leadbelly, don’t know if you’ve heard of him? Anyway, he was a prisoner in, I guess it was Texas State Prison, and I forget what his real name was but people just called him Leadbelly… He was recorded by a man named Alan Lomax, I don’t know if you’ve heard of him? Great man, he’s done a lot of good for music…. Anyway, he got Leadbelly out and brought him up to New York. And he made a lot of records there. At first he was just doing prison songs and stuff like that… Same man that recorded him also recorded Muddy Waters before Muddy Waters became a big name. Anyway, Leadbelly did most of those kind of songs. He’d been out of prison for some time when he decided to do children’s songs and people said oh, why did Leadbelly change? Some people liked the old ones, some people liked the new ones. Some people liked both songs. But he didn’t change, he was the same man!…

Unlike some of his earlier onstage ‘rants’, Dylan is not attempting to make any ‘religious’ points here. Through his invocation of one of his blues heroes, he seems to be delivering a (somewhat confused) admission to his audience (or perhaps to himself) that, despite the plethora of religious material he is still performing, he is – like Leadbelly – ‘the same man’. This indeed is the dynamic substance of the song, in which he triumphantly reasserts his poetic powers. The third and fourth variants are more rhythmic, while the fourth (released on Biograph) even contains ‘whooshing’ noises imitating the sound of waves being driven by the wind. All four versions look back on a relationship that has now ended. As the song evolves Dylan appears to be gradually distancing himself from the experiences which had inspired his gospel albums.

The Biograph version does, however, commence with some striking Biblically-derived imagery: … She was the Rose of Sharon from Paradise Lost/ From the city of seven hills near the place of the cross… ‘Rose of Sharon’ is a very beautiful black woman in the Old Testament Song of Songs. The association with this character also implies the distinct eroticism that characterises the Biblical verses. In Precious Angel (1979) and Covenant Woman (1980) Dylan makes it quite explicit that his conversion was connected to a relationship with a particular black woman. ‘Rose’ is said to be from Paradise ‘Lost’. One may assume that the ‘City of Seven Hills’ refers here to Jerusalem, although the term often refers to Rome. Both are, of course, Christian religious centres, clearly indicating the character’s religious heritage.

In the first version, the woman’s blackness is specifically emphasised: …She was from Haiti, fair brown and intense… (‘fair brown’ being a colloquial term for a beautiful black woman). In the studio outtake she is described as …well rehearsed, fair brown and blonde… (presumably with dyed blonde hair). From the outset, doubts about her character are already being expressed. The initial …I don’t think she’d ever known about innocence… later becomes an insinuation about her influence on all kinds of people: …She had friends who were busboys and friends in the Pentagon… Dylan tells us that …I was playing a show in Miami in the Theatre of Divine Comedy… (in earlier versions ‘the theatre of mystery’). This is somewhat fanciful, as no such location actually exits. Divine Comedy refers to Dante’s great medieval poem about a descent into hell. Dante’s epic is dedicated to his idealised lover Beatrice, who symbolises divine love. The next line suggests that it was this ‘Rose of Sharon/Beatrice’ figure who was responsible for the narrator’s conversion: …Told about Jesus/ told about the rain… ‘Rain’ is a very common image in Dylan’s songs, often symbolising intense emotion, as in Buckets of Rain or hidden truths, as in A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall.

A line used in the earlier versions …She told me about the vision, told me about the pain/ That had risen from the ashes and abided in her memory… makes is clear that the woman has had a very hard life. In later versions this is replaced by what appears to be a reference to Vietnam: … She told me about the jungle where her brothers were slain… which is followed by the mysterious …by the man who invented iron and disappeared so mysteriously… The reference appears to be to the Biblical character Tubalcain, described in Genesis 4:1 as the first blacksmith, who according to Hebrew scholars actually killed his ancestor Cain but was then accidentally killed by his father Lamech. This fate is, however, disputed by some scholars, which may explain the ‘mysterious’ disappearance. However, in the printed text on the official Bob Dylan website (for which Dylan appears to have revised the lyrics yet again) this line is replaced by …By a man who danced on the roof of the embassy… another apparent Vietnam allusion, referring to the US airlift at the end of the war as US officials escaped the wrath of the conquering Viet Cong. Thus ‘Rose of Sharon’ appears to be both a real person or a mythical figure. This is, after all, a dream…

The narrator continues to cast suspicion on the woman …Was she a child or an angel? Did we go too far?… questions her semi-mythic status. Then we are jolted between more war imagery and an apparent Biblical reference: …Were we sniper bait? Did we follow a star?… In each line there appears to be a contrast between myth and reality. In the New Testament, the Three Wise Men followed the star to locate the birthplace of Jesus. Here the narrator appears to be asking if his own ‘spiritual journey’ was actually real or whether he was being manipulated. He may have become suspicious that the Vineyard Fellowship, the ‘born again’ group that his lover had introduced him to, had been using him – as a celebrity or ‘a star’ – for publicity purposes. In a rather surreal touch, however, it is asked whether they ‘followed the star’ …through the hole in the wall to where the long arm of the law cannot reach… The ‘Hole in the Wall Gang’ was a collection of Western outlaws, including Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, whose hideout was located in a mountain pass in Wyoming. This peculiarly American image seems to suggest that the members of this group took their intervention into his private life too far. He wonders …Could I have been used and played as a pawn?… He continues to speculate that …It certainly was possible as the gay night wore on/ When men bathed in perfume and practiced the hoax of free speech… Here, in a dream-like transformation, they seem to have been transported into one of San Francisco’s gay bath houses. On the official website the last line is changed to …celebrated free speech… It seems as if Dylan, in rewriting this rather ambiguous line, may have been attempting to compensate for some of the semi-homophobic ‘stage rants’ he indulged in on his early gospel tours. Most of these were held in and around San Francisco, famed as America’s ‘gay capital’. Such pronouncements were particularly odd, as Dylan had many gay friends, including his great buddy the poet Allen Ginsberg.

These are perhaps the most problematic lines, although many listeners – entranced by the song’s sweeping energy – would be unlikely to pick up on them. In the first recording this verse begins on a more straightforward, if somewhat sanctimonious, note: …Was she a virtuous woman? I really can’t say/ Something about her said “Trust me anyway”… Here there appears to be another male character involved, whom the narrator is suspicious of. He tells us that he pretends to be asleep but that really he is watching this interloper carefully. This is conveyed through the rather wonderful line … I was only paying attention like a rattlesnake does…. Quietly, in other words, but menacingly, and ready to strike if necessary… In the first studio version the pronoun related to ‘rattlesnake’ is changed to a ‘he’. Whether this is actually a third person or merely the narrator viewed from a ‘different angle’ is open to question. But in all the versions, definite seeds of doubt are sown here. The narrator seems very unsure whether to trust his ‘angel’.

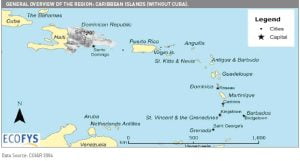

The song’s distinctive chorus remains mostly unchanged. The last two lines …And them distant ships of liberty on them iron waves so bold and free/ Bringing everything that’s near to me nearer to the fire… seem to suggest the narrator looking out on the waves of the Caribbean as if he is staring back into history. The Caribbean was the site of mass slave plantations in the early days of the British Empire. Perhaps the ‘ships of liberty’ are ships on which such slaves were making an escape. But to the narrator, they seem to represent the idea that his own ‘liberty’ as a thinking person and artist has been compromised. Now they seem to be sailing towards him, across the water to the fire which in the earlier part of the chorus is memorably referred to as the ‘furnace of desire’. Yet they are still distant, perhaps on the far horizon, trapped on unmoving ‘iron waves’, as if stuck in the Bermuda Triangle. The opening lines of the chorus in the final version are: …And them Caribbean winds still blow from Nassau to Mexico/ From the circle of ice to the furnace of desire… In the earlier versions the place names are different. There the winds blow …from Mexico to Curacao… and …from Trinidad to Mexico… The names of locations around the Caribbean are largely interchangeable. All of them are experiencing the wind that blows towards the mysterious …furnace of desire…. providing it with the oxygen it needs.

The imagery is powerfully hallucinatory here. Have the ‘ships of liberty’ encompassed the whole world, sailing here from the frozen poles? What is certain is that the sound of the waves (actually given a physical representation here) appear to be calling to the narrator, as if he is grasping for freedom from the ‘iron waves’ of religious dogma in which he has become becalmed, or perhaps into which this supposedly ‘virtuous woman’ has led him. One is reminded of the passage in Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner in which the ship, which is sailing on a kind of ‘spiritual voyage’, is indeed becalmed:

…Down dropt the breeze, the sails dropt down,

‘Twas sad as sad could be;

And we did speak only to break

The silence of the sea!

All in a hot and copper sky,

The bloody Sun, at noon,

Right up above the mast did stand,

No bigger than the Moon.

Day after day, day after day,

We stuck, nor breath nor motion;

As idle as a painted ship

Upon a painted ocean…

Although its final three lines are little changed, the third verse seems to be the one Dylan struggled with the most. In the original version the verse begins with the memorably visual image of …Our shadows are closer until they touched on the floor… which suggests that the relationship in question is somehow lacking in ‘substance’. This is rhymed with …Prodigal sons waiting close to the door… indicating that they are soon going to be betrayed. These ‘prodigal sons’ are …preaching obscenities, waiting for the night to arrive… This appears to imply that figures who are preaching some kind of ‘false religion’ are threatening to tear the relationship apart. In the live version there is only one ‘prodigal son’ (apparently a more sympathetic figure) who is now ‘preaching resistance’. It seems that this third figure may or may not be the narrator himself (viewed from a different perspective) or another character who is threatening the relationship. The fourth and fifth lines, which remain unchanged in all four versions, are …He was well connected, but her heart was a snare/ And she had left him to die in there… as if her ‘heart’ is some kind of dangerous trap. The consistent suggestion is that the female figure is some kind of dangerous seductress. But Dylan remains unsure about this. In the first version we hear that …But I knew I couldn’t get him out while he was still alive… In the live rendition this is reversed: …I knew he could get out while he was still alive… By the first studio version this becomes the rather less threatening ….He had payments due and he was a little behind… In each case, this third figure seems to have been taken in by the woman.

In the released version Dylan revises the whole verse. We hear that there is …a sea breeze blowing, there’s a hell hound loose… echoing Robert Johnson’s blues classic Hellhound on My Trail… and suggesting that the woman is in the grip of some kind of demonic possession, as if she is a practitioner of voodoo (a religion which originated in Haiti). We hear that there are …Redeemed men who have escaped from the noose/ Preaching faith and salvation… suggesting that these ‘men’ are, like the zombies in voodoo, some kind of ‘walking dead’. We hear that their victim is …going down slow, barely staying alive… In these nightmare visions we hear various versions of how a man is ensnared and corrupted by the woman’s dark spiritual power. He becomes convinced that she has been drawing him into the ‘furnace of desire’ in order to destroy him.

We then jump into the present tense, in which the narrator appears to be lying on a bed in the heat, in a cheap hotel room, where the ceiling fan is broken and there are …flies buzzing my head… We may assume that the narrator is experiencing a kind of ‘fever-dream’ in which the figure of the woman appears to him as a succubus, draining away his spiritual sense with her seductive sexual power. In a verse which changes little through the four versions, and therefore may provide the essential ‘key’ to the whole song, we hear that he hears a street band outside playing Nearer My God to Thee. This popular hymn was originally composed in 1941 by the English poet and hymn writer Sarah Flower Adams. It is a meditation on death which takes its inspiration from the description of Jacob’s dream in Genesis 28:11-12 (which, with its description of a ‘ladder to the stars’, was also alluded to in Dylan’s 1974 song to his new born child Forever Young):

…And he lighted upon a certain place, and tarried there all night, because the sun was set; and he took of the stones of that place, and put them for his pillows, and lay down in that place to sleep.

And he dreamed, and behold a ladder set up on the earth, and the top of it reached to heaven: and behold the angels of God ascending and descending on it….

The narrator’s dream is, however, rather different to Jacob’s inspiring vision. It appears that the woman has trapped him in a kind of death-spiral. In the final version he meets the woman ‘at the station’ (one of the ‘stations of the cross’ perhaps) where she sneeringly tells him that …I know what you’re thinkin’, but there ain’t a thing/ You can do about it, so let us just agree to agree… Here Dylan twists around the colloquial saying ‘agree to disagree’ to indicate her manipulative power. A particularly distinctive variation occurs in the live version of the song, in which (although the lyrics are not easy to decipher) Dylan appears to be singing that the buzzing flies are …slaying Bob Dylan in my bed… This is the only time in his entire career that he uses his own name in a song. One may speculate that the line was improvised, but it does appear to indicate just how personal he felt the song to be. The implication appears to be that the woman’s seduction of the narrator into a religious frenzy has ‘killed Bob Dylan’, having stolen his poetic soul. In the many ballads on the subject, Nearer My God to Thee is traditionally said to be the tune which the band on the Titanic played as the ship went down. It is a hymn whose narrator is preparing to meet her maker, again suggesting that the narrator of Caribbean Wind has experienced a kind of ‘spiritual death’.

We are reminded, however, that the Caribbean Wind – a mystical force which blows across the world, from the icy poles to the burning, passion-blinded heart of the narrator, continues to swirl around him. It seems that this is a wind that represents the liberation of the mind from dogma. Meanwhile, ‘distant ships of liberty’ are approaching, presumably coming ‘nearer’ to stoke up his renewed creative fire. Perhaps ‘Bob Dylan’ really had been ‘slain in his bed’. But a new ‘Bob Dylan’ is emerging, not as a ‘born again’ Christian but as a ‘born again’ mystic poet.

The last two verses of the final version bring the song to an evocative climax, as the narrator’s dream explodes with apocalyptic force. The opening lines of the next verse are among the most heartrending in Dylan’s entire ouvre: …Atlantic City by the cold grey sea/ I hear a voice crying “Daddy!”/ I always think it’s for me/ But it’s only the silence of the buttermilk hills that calls… It is hard not to imagine that Dylan, who had been through an acrimonious divorce a few years before, is expressing the awful hollowness he feels inside in missing his children. It now seems, however, that the narrator may not actually be in the Caribbean but in the more prosaic location of Atlantic City on the US’ North East coast. The Buttermilk Hills are a very barren, boulder-strewn location at the edge of the Sierra Nevada desert in California. In his anguished dream, the narrator hears the plaintive voice of his child calling him from the other side of the continent.

These lines remain virtually unchanged in the four versions of the song, as do the final three lines, with the very Dylanesque piling up of apocalyptic imagery, recalling songs such as A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall and Idiot Wind: …Every new messenger bringin’ evil reports/ ‘Bout riotin’ armies and time that is short/ An’ earthquakes and train wrecks and hate words scribbled on walls…. Under the influence of the Vineyard Fellowship, Dylan appeared at one time to really believe that the End of the World was about to occur. In the middle of his post-conversion religious fervour, in one of his stage rants, earlier in 1980, he had spouted his belief that the Battle of Armageddon was about to occur in the Middle East. This battle would, Dylan asserted, bring about Jesus’ Kingdom on Earth, as prophesised by the book of revelations. The members of the Vineyard Fellowship, under the influence of Hal Lindsay’s 1970 bestseller The Late Great Planet Earth, as well as the notoriously racist and homophobic TV evangelist Jerry Falwell, appeared to subscribe to this view. Meanwhile, Ronald Reagan was engaged in what would be his successful run for the Presidency. The former Hollywood star’s rule brought about the tensest era in international relations since the Cuban Missile Crisis, as America’s nuclear armaments were built up to counter a supposedly increased ‘Soviet threat’. In several of his pronouncements, Reagan himself appeared to take the idea that nuclear war might be the fulfilment of the Book of Revelations quite seriously.

Dylan’s narrator, in the midst of his fever-dream, adopts a rather mocking tone towards all these ‘prophecies’. It appears that he is now admitting that he was sucked into believing some of the frankly bizarre right wing prophecies that the Vineyard group espoused. The final ‘hate words scribbled on walls’ expresses the contempt he now feels that the ‘slain Bob Dylan’, the author of Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall, arguably the most powerful and desolately beautiful expression of anti-apocalyptic defiance ever composed, had been duped into following the tenets of a religious cult.

This feeling of disgust is eloquently expressed in the devastating first couplet of the last verse of the final recorded version: …Did you ever have a dream that you couldn’t explain?

Did you ever meet your accusers face to face in the rain?… which appears to confirm that the whole song has been a dream, experienced perhaps in a ratty seaside hotel in Atlantic City. There is a strong suggestion that Dylan has had some kind of confrontation with those who engineered his conversion. Just as, in the New Testament, Jesus frequently faces his accusers, these lines suggest Dylan himself facing up to false accusations in the midst of a ‘hard rain’. But it seems that he has a new kind of inner strength, as that ‘Caribbean Wind’ is now behind him, ready to blow all his illusions away.

We then get one more lucid, desire-filled memory of the woman: …She had chrome brown eyes that I won’t forget as long as she’s gone… followed by the narrator’s own slyly comic version of the apocalypse that he had been duped into believing to be an inevitable, even desirable, historical certainty: …I see the screws breakin’ loose… he exclaims …see the devil poundin’ on tin… I see a house in the country bein’ torn from within…

The final line …I can hear my ancestors calling from the land far beyond… strongly suggests that the narrator, with his ear cocked to that all-powerful Caribbean Wind, has now experienced a different kind of spiritual awakening. Some commentators have theorised that this indicates Dylan’s ‘return’ to Judaism; a theory that is backed up by some of the imagery in the songs of 1983’s Infidels (especially in Dylan’s rather crass defence of the state of Israel in Neighbourhood Bully). Yet, despite his career-long use of Biblical imagery in his songs, Dylan never professed to be a regularly practising Jew. The line itself is deliciously ambiguous. Many spiritual traditions, including those of Native American shamanism, Shintoism and Australian Aboriginals, revere or even ‘worship’ their ancestors. The line appears to suggest a particular type of visionary experience that Dylan underwent. But it was not one he could easily explain, or put a name to. In the cathartic process of writing – and constantly rewriting – Caribbean Wind he appears to have tried, and perhaps failed, to figure out what the ‘revelations’ of the last few turbulent years have taught him. But perhaps there never was a solution to the puzzle of the song. Spiritual truth is, after all, a matter of perspective. Maybe he needed to work through all four versions to express the complexity of the experience itself. Singing from these four different perspectives, recounting four different dreams, he draws us into a surreal and ever-changing landscape which, like any individual’s perception of ‘spiritual truth’, only makes sense through ‘the eye of the beholder’. Caribbean Wind is thus a song which could never be truly ‘finished’ but whose story exists in several different dimensions at the same time.

DAILY DYLAN NEWS at the wonderful EXPECTING RAIN

THE BOB DYLAN PROJECT- COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

Leave a Reply