Another song which pokes fun at the media process in a more obvious way is the rollicking Million Dollar Bash. This song has a more obviously light hearted tone, epitomised by the comical chorus which consists merely of the twice repeated …Oooo baby, ooo-eee!.. followed by …It’s that Million Dollar Bash!.. The song lumbers on in a rhythm dominated by Rick Danko’s bass. Danko and Manuel give support on the sing-a-long refrain. Here Dylan again uses more absurdist imagery and the substitution of key words for comic effect, taunting listeners and challenging them to make sense of apparent nonsense. At the end of every verse, we are told that all the bizarre characters we will be introduced to will be meeting up at the fabled ‘bash’ – presumably the ‘party of the century’.

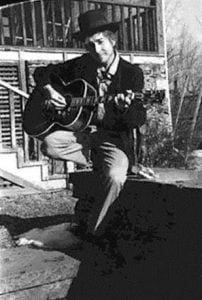

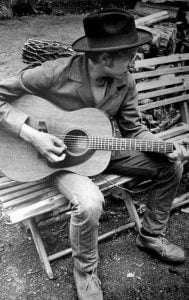

DYLAN IN WOODSTOCK

The song begins with a delightfully mocking portrait of figures who one might liken to a Hollywood star and a member of her entourage arriving at the Oscars or some similarly self congratulatory showbiz ceremony: …That big dumb blonde/ With her wheel in the gorge/ And Turtle, that friend of hers/ With his checks all forged… The ‘big dumb blonde’’s ‘friend’ is presumably her manager, who is described as having …His cheeks in a chunk/ And his cheese in the cash… This actually makes very little literal sense but gives a brilliantly comical picture of the money-motivated ‘Turtle’. Among the other attendees are characters with more splendidly random names such as ‘Sweet Cream’ and ‘Silly Nelly’. Dylan even throws in the line …Along Came Jones/ And emptied the trash… referring to two 1950s Leiber-Stoller novelty songs by The Coasters, Along Came Jones and Yakety Yak. Midway through the song, we again shift into a first person narrative, including a wonderful description of what it is like to have a hangover: …I’m hitting it too hard/ My stones won’t take/ I get up in the morning/ But it’s too early to wake… Finally the narrator snaps out of this by ‘punching himself in the face with his fist’ and declaring, in a completely random way, that …I took my potatoes down to be mashed…

Million Dollar Bash is undoubtedly a romp, particularly suited to live performance, although Dylan has only performed it live once (in 2005). It has been covered by many artists including Fairport Convention, who put out a drunkenly raucous version on their classic album Unhalfbricking (1969). Like The Mighty Quinn, it can be read as an extremely ‘left field’ comment on the falseness of the trappings of fame in general. It may also be another very coded statement about why Dylan has retreated from the ‘media circus’ of being in the public eye. It shows the ‘big party’ that all the characters are headed for to be an essentially hollow and meaningless event.

Dylan takes the genre of the ‘drunkard’s song’ to the extremes of comic absurdity in Please Mrs. Henry, which again features a chorus that Dylan and his band members can relish while delivering the plaintively desperate and befuddled cry of …Please Mrs. Henry, Mrs. Henry please… (repeated)… I’m down on my knees/ And I ain’t got a dime… The song begins with the rather splendid declaration that …I’ve already had two beers and I’m ready for the broom… which rhymes neatly with the request to Mrs. Henry (presumably a landlady of a drinking establishment of some kind) to …Take me to my room… The song is delivered with a kind of distinctively drunken logic, including a line few of his fans could ever believe Dylan would deliver: …I’m a good ol’ boy… a favourite expression of Southern ‘crackers’. The inebriated narrator declares that he has been …sniffin’ too many eggs… and later boasts, in a surreal quatrain that stretches ‘animal metaphors’ to the limit: …I can drink like a fish/ I can crawl like a snake/ I can bite like a turkey/ I can slam like a drake… As the song continues the narrator appears to be growing more desperate to relieve himself. …Don’t crowd me lady… he pleads …Or I’ll fill up your shoe… and later, rather hilariously …I’m startin’ to drain/ My stool’s gonna squeak/ If I walk too much farther/ My crane’s gonna leak… implying that, unless he receives her help, he will soon wet himself. No response from Mrs. Henry is recorded, so we can only conclude that this does not end well.

Yea! Heavy and a Bottle of Bread

Yea! Heavy and a Bottle of Bread is another ‘drunkard’s song’ but with perhaps a little more substance. The chorus merely repeats the title line three times in the first and fourth verses, while verse two gives us three lots of …Get the loot, don’t be slow, We’re gonna catch a trout… and verse three ends with the repeated …Take me down to California, baby!… This is perhaps the most surreal song from The Basement Tapes, beginning as it does with the line …Well, the comic book and me, we caught the bus… which is repeated in the final verse. We are also told that his female chauffeur has caught a cold and is in bed … with a nose full of pus… Dylan delights in offhand internal rhymes such as …It’s a one track town, just brown… Despite the participants having ‘caught the bus’, we are later told that they are in the song are heading …for Witchita in a pile of fruit… The singer implores someone to …Pull that drummer out from behind that bottle… and later, in a very slapstick moment, to …Slap that drummer with a pie that smells… The whole thing has the logic of a dream, which is enhanced by more ‘spooky’ backing vocals from Danko and Manuel. Like Mrs. Henry, this is a song with little serious intent, but its almost complete detachment from logic puts it in a category of its own in Dylan’s oeuvre. This is certainly nonsense, but sublimely funny and ‘cool’ nonsense. On its only two live performances in 2002 and 2003, it was greeted rapturously by audiences delighted to have the chance to hear such an obscurity.

Don’t Ya Tell Henry

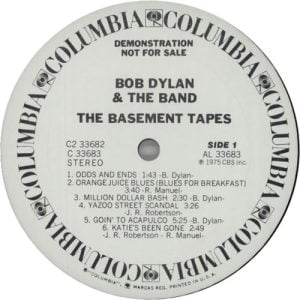

Don’t Ya Tell Henry is another splendidly drunken ramble which later became a staple of The Band’s live set. The first official release of The Basement Tapes in 1975 featured a ‘cleaned up’ version performed by The Band with Levon Helm on vocals. This is a far more ‘professional’ take than the original version where Dylan sings, but here the whole band appears to be having a ball, joining in with raucous backing vocals. The song was performed only once by Dylan, during his guest appearance with The Band at the Academy of Music in New York on December 31st 1971. The Basement recording is dominated by Rick Danko playing a rather ludicrously out of tune trombone, which is prominent throughout the track and is even featured in an extremely wonky solo. However, the amateurishness of the playing only adds to the joi de vivre of the track. Again the song has a simple and very catchy chorus: …Don’t You Tell Henry (repeated)/ Apple’s got your fly!… There is no indication that ‘Henry’ is any relation to ‘Mrs. Henry’ in the other song.

Don’t Ya Tell Henry is great fun, delighting in satirising clichés from country, gospel and blues songs. The first song begins with a line from many gospel songs: …I went down to the river… The protagonist discovers …a little chicken, down on his knees… and is apparently so drunk that he talks to the animal. pleading with him not to ‘tell Henry’. We never find out what Henry should not be told although we might presume that he needs to be warned about some terrible event. Perhaps his apples have been eaten by flies, although the chorus actually suggests the opposite. The song appears to describe, in its rather delirious way, how the main character is ‘searching for himself’. In the third verse he goes …down to the beanery… (an American term for a cheap restaurant)… a-lookin’ around just to see myself… He then encounters a group of farm animals, who give him the usual message. In the final verse he ends up in a whorehouse but the building is apparently empty. He goes upstairs and, as his drunken delirium begins to clear, finally concludes that …I didn’t see nobody but me…

Lo and Behold

Lo and Behold is another bizarre absurdist travelogue. Here Dylan pushes his experimentation with nonsense verse to the extreme. The song could be said to be satirising those who expect him to be some kind of prophetic truth teller or the ‘voce of a generation’. The expression in the title, which has a Biblical origin, is usually related to a surprising revelation, but is frequently used ironically to indicate disappointment at something that is not really new at all. In this song the narrator appears to feel hemmed in or trapped by expectations of him, and so reverts to nonsensical explanations. The song features another simple chorus: …Lo and behold, lo and behold/ Looking for my lo and behold/ Get me out of here my dear man… to which Manuel and Danko add comically exaggerated vocal harmonies. Dylan speaks rather than sings the lines in the verses, in the manner of country vocalists in their more moralistic moments. Half way through the first of the two Basement Tapes versions, Dylan collapses in laughter after accidentally repeating a lyric. But this only adds to the charm of the piece, which features the first person narrator engaging in unlikely travels across the USA. At first he sets out from San Antone in Texas, arrives in Pittsburgh, announces his intention to go …down to Tennessee… but ends up back in Pittsburgh again. The woman who he is supposed to meet in San Antone never materialises. His travels are beset by absurd difficulties. On his first journey we hear that …the coachman he hit me for my hook… The reference to a ‘coachman’ seems to place the action in the distant past but the phrase, though comically resonant, is deliberately obscure. We also hear that, when the narrator tells the coachman his name, he ‘hangs his head in shame’. But none of this is really explained.

The second verse is the most wildly surreal and hilarious. When the narrator arrives in Pittsburgh we hear that …I found myself a vacant seat/ And put it down my hat… The following lines consist of a very weird conversation for which we are given no context: …What’s the matter with you Molly dear?… The narrator asks …What’s the matter with your mound… She replies …What’s that to you, Moby Dick? This is chicken town!… At a stretch, one might see these names as references to James Joyce’s Molly Bloom, famed for her explicitly sexual monologue in Ulysses, and Herman Melville’s classic. The use of the terms ‘mound’, ‘dick’ and ‘chicken’ may be sexual innuendo. The narrator certainly seems to be searching for some kind of sexual fulfilment, which he clearly will not ever find. In the third verse he tells us he buys his girl …a herd of moose/ One she could call her own… But the next day she comes back to him enquiring where they had flown away to. The narrator’s response is to vow to …get me a truck or somethin’… and to run away to Tennessee. To express the futility he feels, he memorably declares that he will …Save my money and rip it up!… The journey back to Pittsburgh is carried out on a ferris wheel. ..Boys I sure was slick… he boasts, telling us he will …Round that horn and ride that herd… Whether he is referring to the ‘herd of moose’ is unclear. Lo and Behold is arguably the most ‘nonsensical’ of these songs. Its narrator is searching for something but, like Mr. Jones in Ballad of a Thin Man, he really does not know what it is.

Goin’ to Acapulco

Another song which is marked by sexual innuendo is Goin’ to Acapulco, a languid ballad with some highly emotive vocalising by Dylan, backed by a distinctive swirling organ from Hudson. In terms of its subject matter the song (which at 5.25 is one of the longest in The Basement Tapes) is a clear precursor to The Band’s masterpiece The Weight which appears on Music from Big Pink. There is even a distinctive chord progression at the end of each chorus which appears in Robbie Robertson’s song. As in The Weight the protagonist is a dissolute fellow who resolves his troubles by visiting his favourite prostitute. Danko and Manuel again add strong support to the choruses. The song is a kind of intimate confession, perhaps of the kind of sexual incontinence that those who become famous stars may fall victim to. As Dylan proclaims, a little menacingly …I’m just the same as anyone else when it comes to scratching for my meat… He tells us that Rose Marie, the prostitute …Never does me wrong/ She puts it to me plain as day/ And gives it to me for a song… The use of the expression ‘for a song’ generally indicates an especially cheap deal. But here the intimation may be that the narrator is someone who, like Dylan, sells himself through his songs and thus is himself a kind of ‘prostitute’. …It’s a wicked life… the narrator proclaims …But everybody’s got to eat… It is later suggested that, given all the ‘free service’ he gets at Rose Marie’s, he is some kind of pimp …It’s not a bad way to make a living… he tells us in an aside …And I ain’t complainin’ none… The sexual innuendo in …I can pull my plum and drink my rum… is fairly obvious here, as it is in the later …Every time the well breaks down I just go pump on it some…

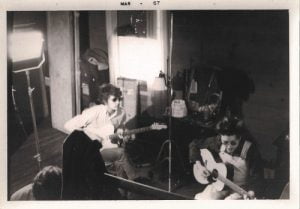

DYLAN IN THE BASEMENT

The strangest line in this oddly passionate confessional occurs near the end, in which the narrator shares with us that …if someone offers me a joke, then I just say ‘No thanks’… It is tempting to interpret this as the narrator turning down offers of drugs, especially as part of the process of The Basement Tapes may be ‘drying out’ from excessive drug use. Goin’ to Acapulco is, despite its apparently nonsensical elements, a heartfelt performance which, unlike the other ‘nonsense songs’, does not attempt to be funny but instead gives us a sad evocation of the results of excess. Although the narrator proclaims his satisfaction with his situation, the tone of extreme regret in the delivery of the song appears to contradict this.

Open the Door, Homer

Open the Door, Homer uses nonsensical logic in a different way. The song has another rousing chorus: …Open the door, Richard, I heard it said before/ Open the door Richard/ And I ain’t gonna hear it said no more… Open The door, Richard was a very popular song widely featured in minstrel shows in the 1940s, in which blackface performers (some of whom were actually African Americans) acted out the scenario of a drunken man knocking on a door and trying to gain admittance. Why Dylan chose to use this phrase instead of the apparent title of the song is something of a mystery. It might be argued that in naming the song he was making some kind of reference to the author of the foundational texts of Western literature. Homer did indeed ‘open the door’ to epic forms of storytelling. But the ‘Richard’ reference makes more sense as the song introduces us to a series of apparently nonsensical paradoxes that cannot, by their nature, be explained logically. These strange homilies will never help gain admittance to wherever the door leads to. It might be argued that the door leads to a world of everyday ‘common sense’.

In the first homily, the lugubrious narrator, adopting the tone of an ‘ol’ timer’ in a Western, ‘chewing the fat’ over his bacon and beans, tell us …Now there’s a certain thing/ That I learned from Jim/ That he’d always make sure I’d understand/ And that is that there is a certain way/ A man must swim/ If he expects to live off the fat of the land… We never find out who ‘Jim’ might be. In fact his name, and that of the narrator’s other friends Mouse and Mick, seem to be chosen because they produce neat rhymes. In the second verse ‘Mouse’ (who we are told is …a fella who never blushes… advises the narrator that …one must always flush out his house/ If he don’t expect to be housing flushes… Both of these paradoxes take us into Lewis Carroll territory. Dylan enunciates with great sincerity, despite the apparently drunken context. The song makes a virtue of stating the obvious, in a curiously ironic way. The third homily, delivered by ‘Mick’, is more pointed: …Remember when you’re out there trying to heal the sick/ That you must always first forgive them… This may be considered to be something of a barb directed at sanctimonious religious people but this – as well as the previous statements – also have a highly ironic undercurrent. The door to common sense will never be opened for Richard (or Homer) and he will remain perpetually trapped by his own logical limitations. The song can therefore be seen as a comment on false intellectualism or religious belief. The sly inference in the last verse about healing depicts the narrator as someone who aspires to the role of ‘prophet’ which Dylan himself rejects so vociferously.

You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere

Perhaps the most appealing of this group of songs is You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere, which has attracted multiple cover versions and has become an ‘alt country standard’. It was played around hundred times on the Never Ending Tour between 1997 and 2012. A whimsical piece of supposed ‘nonsense’, with an attractive and catchy melody, it is built around another logical paradox, with a sweetly appealing chorus: ...Ooo-eee, ride me high/ Tomorrow’s the day/ My bride’s gonna come/ Ooo-eee, we’re gonna fly/ Down in the easy chair… The Byrds’ version on their first ‘country rock’ album Sweethearts of the Rodeo (1968) is perfectly paced, with the addition of a mournful steel guitar. There are two versions in The Basement Tapes, the first of which appears to have mostly ‘dummy lyrics’. By the time the second take is recorded, Dylan has refined the song considerably. It now opens a quite exquisite run of two rhyming couplets: …Clouds so swift/ Rain won’t lift/ Gate won’t close/ Railings froze… Dylan grew up in and is thus highly attuned to the weather of the ‘North Country’. Here he delights in the beauties of winter. The narrator appears to be addressing someone who has no choice but to stay put. He is probably addressing himself. But, unlike the frustrated protagonist of Open the Door Homer, he has nothing to prove. The song has often been linked to Dylan’s period of recuperation after his motorcycle accident, when he was indeed trapped in an easy chair while his mind was ‘riding high’ with new perspectives and ideas.

The song has several delicious rhymes, especially in the third verse: …Buy me a flute/ And a gun that shoots… Dylan sings …Tailgates and substitutes/ Strap yourself to the tree with roots… He sounds quite content to be in this situation. A ‘tailgate’, as well as being the part of a truck that can be lowered to load up goods, is also a style of improvised trombone playing favoured by early jazz musicians in New Orleans. ‘A Tree With Roots’ was the title of one of the more comprehensive bootleg collections of The Basement Tapes; no doubt considered to be an appropriate title for the whole collection. In itself it is a tautology – all trees do, of course, have roots. But this is the kind of wordplay that Dylan loves. The title of the song is yet another of his distinctive double negatives, which is especially effective here. The subject of the song may be stuck in his chair in a physical sense but his mind is, in contrast, decidedly heading ‘somewhere’.

The final verse features a striking logical and historical shift: …Genghis Khan he could not keep/ All his kings supplied with sleep/ We’ll climb that hill no matter how steep/ When we get up to it… The final line indicates the main character’s determination to eventually get out of his chair and ‘climb every mountain’ in his future life. Nothing will hold him back. The earlier lines again hint at the use of ‘sleep’ as a metaphor for mind altering substances. Genghis, like virtually all the other briefly mentioned characters in The Basement Tapes, is presumably using a pseudonym. Maybe he is a drug dealer from town that the character is waiting for. Or perhaps the line indicates the powerlessness of the mighty when dealing with ordinary human needs, again emphasising the narrator’s message that patience is now very much required. Sleep will be coming soon, it seems.

Although this was the standard set of lyrics that Dylan later used when the song became a staple of his live act, when he re-recorded the song in 1971 for the More Greatest Hits album (accompanied by Greenwich Village acolyte Happy Traum on banjo, guitar, bass and backing vocals) he substituted an almost completely different set in the verses. This was a rather strange move given that Dylan’s original would not be released for another four years. The song now begins: …Clouds so swift/ Rain falling in/ Goin’ to see a movie called Gunga Din/ Pack up your money/ Pull up your tent McGuinn… In the Byrds’ version Roger McGuinn had sung the lines from verse two as …Pack up you money and pick up your tent… getting ‘pack’ and ‘pick’ in the wrong order, and here Dylan gently mocks his friend for the mistake. The rest of the rewrite is full of verve and zing. We now hear, in a rather obscure reference to the Everly Brothers (Phil and Don) that …Genghis Khan and his brother Don/ Could not keep on keepin’ on… The new final verse is also something of a tour de force, with Dylan clearly delighting in the lines …Buy me some rings/ And a gun that sings/ A flute that toots and a bee that stings… This is followed by another very well considered pair of couplets: …A sky that cries/ And a bird that flies/ A fish that walks/ And a dog that talks… Quite ecstatic and inspired nonsense, of course, but highly amusing and cheerfully uplifting… It is not surprising that the song has become very popular with Dylan cover bands as its swinging style guaranteed to please an audience.

Americana

The Basement Tapes is a unique set of songs in which Dylan and The Band, in searching for musical ‘roots’, can be said to have created the entire genre of ‘Americana’, which now features as an official category for Grammy and other awards. Americana has largely superseded what was once known as ‘folk music’, the artificially ‘pure’ form epitomised by performers like Pete Seeger, Peter, Paul and Mary and the Kingston Trio, who presented American ‘roots music’ in a rather bowdlerised form. In contrast, Dylan gets ‘down and dirty’ here; identifying the American ‘folk past’ as being populated by very dubious characters such as pimps, whores, gangsters and gamblers. And yet these songs are, as we have seen, largely ’suitable for children’. Despite their suggestive subject matter and the apparently nonsensical content of their verses, they all have very attractive and singable choruses. They use humorous lyricism in an extremely artful way to express Dylan’s own disillusionment with the music business and its attendant ‘star system’. At the same time, even many decades after their composition, it is hard to listen to these songs without – at least once – cracking into a smile.

Leave a Reply