…Alice: “If I had a world of my own, everything would be nonsense. Nothing would be what it is because everything would be what it isn’t. And contrariwise, what it is, it wouldn’t be, and what it wouldn’t be, it would…

Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

…. I am he as you are he as you are me and we are all together…

John Lennon, I Am the Walrus

…Talking nonsense is the sole privilege mankind possesses over the other organisms. It’s by talking nonsense that one gets to the truth! I talk nonsense, therefore I’m human…

Fyodor Dostoevsky, Notes From Underground

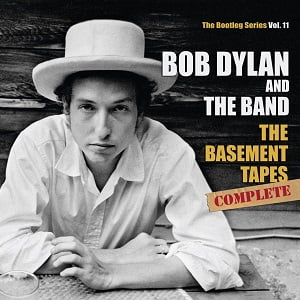

Nonsense Songs from The Basement Tapes

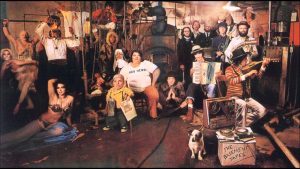

A ‘HAPPENING’ IN SAN FRANCISCO 1967

1967 was arguably the most dramatic year of cultural change in the twentieth century. The newspapers were bursting with salacious reports of ‘love-ins’ and ‘happenings’. Young people were appearing in public in outlandish clothes. Men were growing their hair long and women were abandoning the coiffured look of old. In California thousands of those who they press had labelled ‘hippies’ were taking to the streets. All over the US protests were erupting against the Vietnam War. Although those who took part in the LSD-inspired ‘psychedelic revolution’ were always in a minority, a cultural shift was taking place. The ‘alternative society’ or ‘counter culture’ which first emerged into public view in this epochal year was to have many offshoots, spawning ecological consciousness, feminism, gay rights protests and many other forms of social activism which were to become increasingly influential as the century wore on. Popular music – in particular the genre that was becoming increasingly referred to as rock music rather than ‘rock ‘n’ roll’ – was at the forefront of change. The Beatles, easily the world’s most popular group, led the charge with singles and albums that used poetic lyrics and sonic trickery to duplicate the ‘psychedelic experience’. The ‘Monterey Pop Festival’ in June of that year featured almost all the leading counter cultural American bands and is most remembered today for Jimi Hendrix’s climactic performance of Wild Thing, after which he ritually set his guitar on fire. Revolution, it seemed, was very much in the air, along with many new and exotic smells, tastes and images.

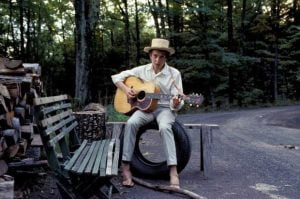

DYLAN AND DANKO AT WORK, 1967

Strangely, though, as far as the world knew, Bob Dylan was merely ‘absent’ through all this. He had been promoted by members of the counter culture as not only their leading intellectual but also a kind of prophet. Many years later, in his memoir Chronicles Vol. One Dylan would express horror at this term being used to describe him. Yet to many young people it seemed that the ‘prophecy’ of a song like The Times They are a-Changin’ had indeed come true. Those sons and daughters really had broken away from the ‘commands’ of their elders. All Dylan would need to do, it seemed, was to make some public appearances to be acclaimed as the ‘leader’ of the movement. But this was the last thing he intended. The years 1963-66 had seen him release six albums, write hundreds of songs and rise to become a household name on both sides of the Atlantic. This period had culminated in the notorious tour of the US, Britain and Australia in which he had been subjected to nightly abuse from outraged folk purists. More tours were planned. But after his motorcycle accident in 1966 he stepped away from the limelight. For the next few years he would remain holed up in Woodstock in upstate New York, spending time with his young and rapidly growing family and with members of his backing group, still known as The Hawks. The music they made together in 1967, recorded by keyboard player Garth Hudson on a reel to reel tape recorder, and which came to be known as The Basement Tapes, remained unreleased for several years.

Nonsense Songs: Sense and Nonsense

In The Basement Tapes Bob Dylan mines a number of popular American musical forms while taking his exploration of the limits of language to a new level. His trilogy of 65-66 albums had included long songs full of cryptic and sometimes hallucinatory imagery such as Visions of Johanna, Desolation Row and Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands, which had undoubtedly been an influence on the burgeoning psychedelic music scene. But after his motor cycle accident and his retreat from touring schedules he began producing shorter, more compressed lyrics featuring lyrical and musical motifs derived from the blues, country, gospel and the various styles of American music that he had thoroughly grounded himself in before becoming a songwriter. One particular group of lyrics from The Basement Tapes has often confounded critics and reviewers, many of whom have concluded that these songs are merely nonsensical pieces and that attempting to interpret them is therefore largely futile. Dylan, we are told, is merely ‘having fun’ with his compadres from The Band, turning out material that they would never expect the wider public to hear, and thus paying little attention to coherence at the expense of spontaneity. Whatever the appeal of the songs, it is alleged that he is merely spouting meaningless gibberish for comic effect.

THE BASEMENT TAPES COMPLETE

It may be argued, however, that such judgements underestimate both Dylan’s engagement with modernist literature and his willingness to experiment with a variety of lyrical forms. These are certainly funny songs, with plenty of bawdy and drunken ironic humour, in apparent celebration of various forms of debauchery. Characterised by apparently absurd or even surreal juxtapositions and set in a mythical American landscape in an uncertain but apparently somewhat archaic time period full of dubious and corrupt characters, the songs, at least at first listen, appear to use language randomly, even to the extent of using invented words. Sense and nonsense appear to be interchangeable. Specific lyrics are often changed in subsequent live recordings of the songs or in Dylan’s edits in the official lyric books. Dylan appears to delight in creating characters here – usually only mentioned once ‘in passing’ – with distinctively funny names. The songs are delivered by Dylan in a deep and lugubrious tone, which is made even more parodic by the deft harmonies supplied by Richard Manuel and Rick Danko. The fact that the tapes were made outside of the conventional setup of modern recording studios, using rather basic reel to reel tape recorders under the supervision of The Band’s keyboard wizard Garth Hudson, and that therefore not all the lyrics are actually intelligible, only adds to the air of mystery and apparent randomness that distinguishes these recordings.

Dark Nonsense in Nursery Rhymes

In 1967 Dylan had recently become a father and – no doubt having been called upon to sing lullabies to his kids – may well be, even if subconsciously, penning material that is reminiscent of nursery rhymes. Many years later, after his second marriage, he would devote most of the nursery rhyme – type songs on the Under the Red Sky album to his latest child. Many nursery rhymes (which, of course, can be considered to be authentic songs in the folk tradition) do have a dark side – Ring a Ring a-Roses, for instance, is said to have originated during the Black Death, as the children ‘all fall down’. In these ‘Basement’ songs Dylan is clearly in this kind of territory. Many of these songs have a dark and mysterious logic which hints at hidden terrors that children are often afraid of.

THE BASEMENT TAPES, THE 1975 ALBUM

At the time of the recording of The Basement Tapes in 1967, Dylan was under some pressure from his management to produce new material. During the recording of the tapes a fourteen song acetate was circulated to various rock musicians and groups with a view to them recording the songs. This may be one reason as to why the material – despite the supposedly ‘impenetrable’ lyrics – uses more conventional musical structures than Dylan’s previous work, as well as distinctive ‘sing along’ choruses. Several covers – including Manfred Mann’s version of The Mighty Quinn and The Byrds’ reading of You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere – became hits for other artists. Dylan’s deliberate engagement with a pop sensibility in the choruses stands in ironic contrast to the gnomic utterances of the verses. The songs are certainly funny but their light heartedness is often counter posed by the far darker suggestiveness of their arcane imagery.

Tiny Montgomery: Scary Nonsense

The first song to be recorded in the basement of Big Pink which displays these characteristics is the bizarre Tiny Montgomery. The song does not have a chorus as such but Dylan’s vocals are backed by high pitched harmonies by Manuel, Helm and Robertson which act as a counter melody to the main tune. This is highly rhythmic and infectious and is driven mainly by Dylan’s acoustic guitar. The song thus has a kind of ‘unsung chorus’ and each verse ends in a refrain indicating that the character will be soon be coming to ‘say hello’. Dylan affects a deeper vocal timbre than usual, which contrasts against the backing vocals to create a mood of considerable uncertainty. This is highly appropriate because we cannot be certain as to what kind of character Tiny Montgomery actually is. The song maintains an ambiguous balance between light hearted banter and a potentially threatening tone.

A nickname like ‘Tiny’ is often given ironically to persons who are extremely tall – a technique known as antiphrasis. One example was the 6ft 1 inch performer Tiny Tim, famous in the late 60s for novelty hits like Tiptoe Through the Tulips and other show tunes from the pre war era, delivered in his distinctive falsetto. Tim had been a friend of Dylan in his Greenwich Village days and actually visited Woodstock in 1967 where he recorded some songs with The Band as backing musicians. The name also conjures up an image of a circus strongman. The use of such a nickname at once infantilises the character but also has a vaguely threatening nature. It is clear from the song that Mr. Montgomery is not a character to be messed with.

DYLAN WITH TINY TIM, 1967

Each of the five verses describes how the inhabitants of ‘ol’ Frisco’ will prepare for Tiny’s arrival, before we are again told that he will be arriving soon. The strident guitar rhythm leads straight into Dylan proclaiming …Well you can tell everybody down in ol’ Frisco/ Tell ‘em Tiny Montgomery says hello… The reference to ‘ol’ Frisco’ immediately suggests that we are in some past time, perhaps in the post-gold rush nineteenth century, when San Francisco became a notorious haunt of criminal gangs. The invocation is immediately arresting. Tiny is then referred to as the bringer of sensual delights: …Every boy and girl gonna get their bang…. Dylan drawls …‘Cause Tiny Montgomery’s gonna shake that thing…. Already the song is infused with sexually suggestive detail, ‘bang’ being a common euphemism for sex while ‘shake that thing’ is a frequently used phrase in the blues relating to sexual displays (as in two different songs with that title recorded by Lightnin’ Hopkins and Wynonie Harris). Several other dubious-sounding characters, including the rather wonderfully named ...Skinny Moo and T-Bone Frank… who we are told are …gonna get on down to the Fountain Bank…. (presumably to draw their money in preparation for Tiny’s visit) are named. The official lyrics change this to …They’re both gonna be getting outa the tank… which makes more sense, as ‘the tank’ presumably refers to the prison that these characters will be exiting (or perhaps escaping from). The next lines: …One bird book and a buzzard and a crow… again have sexual connotations. A ‘buzzard’ is a man who takes advantage of drunken women, a ‘crow’ is a derogatory word for a supposedly ugly woman and a ‘bird book’ may contain a man’s list of potential dates.

The remaining verses take us into ever more obscure and euphemistic territory. The fourth verse contains some advice regarding Tiny’s arrival: …Scratch your dad/ Do that bird/ Suck that pig/ And bring it on home… all of which sounds like rather obscure sexual innuendo. ‘Bring it on home’ is a sexual invitation in a number of blues songs, including one with this actual title by Willie Dixon which was first recorded by Sonny Boy Williamson. Here Dylan stretches the blues convention of creative sexual innuendo to its limits, inferring that the song is to some extent a blues parody …Pick that drain and nose that dough… seems to refer to the act of snorting cocaine, which the narrator seems to be suggesting will be more preparation for Tiny’s arrival. The next verse tells us more about Tiny. We are told that he is the …King of drunks… and, rather memorably, that he ...squeezes too… Advice is given to two more characters …Watch out Lester, Take it Lou… who are told to …join the monks, the C.I.O…. This advice seems to be more for those who wish to avoid the effect of Tiny’s arrival. The initials C.I.O. appear to refer to the Congress of Industrial Organizations, a highly respectable Union organisation in the USA. Perhaps joining this, or a monastery, will help to avoid what will be the devastating effects of the coming of Tiny. In the final verse (which at sixteen lines is twice as long as the others) we return to more preparatory advice. Now Dylan really lets go, indulging himself in a stream of apparently delirious nonsense: ...Grease that gig and play it plain/ Tell them to go out/ And gas that dog/ Trick on in and flour that snow/ Take it all in and begin to grow/ Now play it low/And pick it up/ Take it all in/ In a ball cup…. There appear to be further arcane drug references here, and the concluding reference to a …Three legged man/ And a hot-lipped hoe… seems to be more sexual innuendo.

DYLAN PHOTOGRAPHED IN WOODSTOCK BY ELLIOT LANDY

Tiny Montgomery is a delicious slice of parody, which delights in its own obscurity, mixing well established euphemisms for sex and drugs with more shadowy references. It is possible to read the story behind the song in a number of different ways. Dylan may be sending a strangely coded message to the hippies who are now gathering headlines by appearing on the streets of San Francisco in this, the ‘summer of love’. Perhaps he is sending them a warning about their indulgence in drugs and ‘free love’. The song actually tells us nothing about Montgomery himself (except for his name). Dylan clearly has his tongue firmly in his cheek here. Tiny Montgomery is a very funny song, made more so by the mock-doo-wop vocalisations that contribute so much to its effect. Or perhaps Tiny Montgomery is some kind of super hero, who will come to ‘ol’ Frisco’ and knock out the pimps and drug dealers. The song is a riotously self conscious parody of the kind of euphemistic language – especially referring to matters of sex and drugs – that tends to be espoused by members of what was becoming known as ‘the underground’. At the same time it can be seen as a ‘nonsense song for kids’.

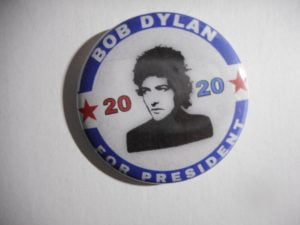

Much of the reason for Dylan’s retreat from the mainstream music scene in 1967 was motivated by his attempt to distance himself from the way that many of the hippies held him up not only as a great song writer but as a kind of prophet or potential ‘leader’ of their movement. ‘BOB DYLAN FOR PRESIDENT’, a famous badge proclaimed, perhaps only half jokingly). Dylan himself, as he reveals in his semi-autobiographical work Chronicles Vol. One (2004), hated this kind of attention. There is little doubt that the ‘nonsense songs’ on The Basement Tapes reflect this attitude, even if in coded form. The way in which the (presumably rather corrupt) inhabitants of ol’ Frisco prepare for the coming of Tiny Montgomery as if he is some kind of messiah may suggest that Tiny’s reputation is way out of proportion to his actual importance.

Another song which takes up this theme more prominently is the more famous The Mighty Quinn (otherwise known as Quinn the Eskimo), of which there are two takes on The Basement Tapes. The British beat group Manfred Mann had a Number One single in the UK with their extremely bright, optimistic and poppy version of the song. Singer Mike d’Abo claimed to have no idea what the verses were about, but the song is made unforgettable by its extremely catchy chorus …Come all without, come all within/ You’ll not see nothing but the Mighty Quinn… which became a very popular chant on English football grounds for several years, especially for supporters of teams containing a player with the surname ‘Quinn’. The alliterative second half of the chorus is another one of Dylan’s distinctive double negatives, while the first part appears to be an almost religious kind of rallying cry. While Tiny Montgomery is a rather flawed Messiah-figure, Quinn the Eskimo’s anticipated arrival will be treated with great reverence. The title of the song was supposedly a reference to the 1960 film The Savage Innocents which featured the Mexican-American actor Anthony Quinn playing the part of Inuk, an Eskimo; although the character in the song has nothing in common with the part Quinn plays in the movie. The song has been covered by many different artists, including The Grateful Dead. Dylan himself has only performed it on a handful of occasions.

MANFRED MANN’S SINGLE OF ‘THE MIGHTY QUINN’

In the two versions on The Basement Tapes Dylan adopts a deep, gravelly vocal tone far removed from the hit single’s bouncy surface. Although The Mighty Quinn is in many ways another light hearted children’s song’, the way it is performed here makes it sound decidedly spooky. This emphasises the comic irony of the piece, as Dylan’s rather nervous sounding narrator delivers another song characterised by highly ambiguous ‘nonsense lyrics’ set against a ‘sing-along’ chorus which Dylan deliberately plays down. The narrator sounds distinctly worried about the imminent arrival of the much-revered Eskimo, despite the man’s apparent status as some kind of saviour. In the first of the song’s three verses, the apparently joyfully optimistic ‘nonsense lyrics’ come over as dryly ironic. …Everybody’s building the big ships and boats/ Some are building monuments/ Others are jotting down notes… Dylan sings slyly, ‘from the side of his mouth’, as he describes the general excitement at the imminent arrival of another Messiah-like figure. As in Tiny Montgomery, there is an intimation of the involvement of children in the narrative: …Everybody’s in despair/ Every girl and boy… with Quinn being presented almost as a ‘Santa Claus’ figure: …But when Quinn the Eskimo gets here/ Everybody’s gonna jump for joy… But Dylan’s deadpan delivery makes these lines sound darkly ominous; an effect which is increased by Garth Hudson’s churchy organ.

In the succeeding verses Dylan adopts the voice of a first person narrator who begins with a kind of personal declaration. He begins with the self-effacing statement …I like to do just like the rest/ I like my sugar sweet… In the first of the two Basement Tapes versions, he cackles memorably …I likes to do… as if he is some cynical old timer watching the whole shebang from the sidewalk, perhaps spitting in the gutter as the parade goes by. The delicious paradoxical ambiguity of the second line can be read as a childish statement but also as a coded reference to sex or drugs. The next lines feature some of Dylan’s most memorable absurdist ‘nonsense images’: ...But guarding fumes and making haste/ It ain’t my cup of meat… Here, as elsewhere on The Basement Tapes, he creates a comic effect but substituting an unexpected word for the obvious one. The expression he works around is the quintessentially British ‘my cup of tea’, usually used to indicate that whatever is being referred to is not what the speaker likes. The rhyming of ‘sweet’ and ‘meat’ is particularly comically effective here, suggesting that whatever the supposedly beneficent Quinn will bring will be more substantial – and potentially indigestible – than his followers might expect. The narrator then observes, a little caustically, that …Everybody’s ‘neath the trees/ Feeding pigeons on a limb/ But when Quinn the Eskimo gets here/ All the pigeons gonna run to him… suggesting that Quinn’s followers are nothing more than dumb ‘birds’ who are only interested in who is providing the most ‘crumbs’.

DYLAN AND THE BAND, ISLE OF WIGHT 1969

The final verse is the most problematical in the song. It is here that Dylan ramps up the ‘nonsense factor’. The opening lines of the Basement Tapes performances are virtually unintelligible, but when the song is first performed – in a cheerfully ‘rocked out’ version at the Isle of Wight Festival in 1969 – we get …A cat’s meow and a cow’s moo, I can recite ‘em all… followed by the apparently random …Just tell me where it hurts you, honey, I’ll tell you who to call… This appears to be some kind of reference to the general malaise that the ‘boys and girls’ are suffering from before Quinn will come to save them. Then, in a wonderfully comic final twist, Dylan tells us that ...Nobody can get any sleep/ There’s someone on everybody’s toes… a rather surreal, or perhaps merely silly, image, which is followed by the knowingly ironic …But when Quinn the Eskimo gets here/ Everybody’s gonna wanna doze… Our saviour will, it seems, be bringing the gift or repose to the citizens. In I’m Only Sleeping from The Beatles’ Revolver (released in the previous year) John Lennon had presented sleeping as a metaphor for stoned intoxication. Here the ‘doze/dose’ double meaning is rather more obviously indicated.

THEM PIGEONS GONNA GO TO HIM…

So is the Mighty Quinn a drug dealer? Is this song, like Tiny Montgomery, a coded warning about the effects of various substances? This is certainly one of the many interpretations which have been placed on the song. As usual, Dylan delights in such ambiguity. Certainly Quinn’s arrival is highly anticipated but the hollowness of his claims to be a saviour are challenged here. The pigeons, we are left in no doubt, will follow him alone. One could also see the song as mocking the way in which some ‘religious’ people follow their leaders blindly, especially as the chorus is modelled on the kind of spirituals that gospel choirs regularly perform. On another level, as with Tiny Montgomery and so many of the Basement songs, the song can be read as an ironic reference to Dylan’s own career, given that his more excitable acid-head followers had acclaimed him as some kind of Messiah. The Mighty Quinn can also be seen as a parody of how the modern media creates ‘false prophets’. When Quinn finally arrives all he really does is send his followers to sleep – or perhaps into a (possibly drug induced) trance. Thus Quinn is a charlatan, a chimerical figure. Not the Messiah, but perhaps something more threatening than ‘a naughty little boy’.

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

THE CAMBRIDGE BOB DYLAN SOCIETY

Leave a Reply