With its stirring chorus and dynamic rock arrangement, 1983’s Jokerman, is one of Bob Dylan’s most memorable songs. It has appeared on a number of ‘Greatest Hits’ compilations and is frequently listed highly on ‘Dylan’s Greatest’ lists. It is a fan favourite. Yet it remains in many ways unknowable. Its highly symbolic imagery, which mixes a number of Biblical and mythological references with echoes of half remembered popular songs, is especially memorable but extremely hard to pin down, so that the song becomes in effect a kind of treatise on ambiguity itself, with the central character of the Jokerman morphing into different forms in every verse.

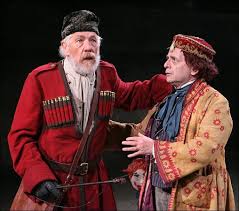

Similar figures to the ‘jokerman’ are prominent in the many traditional ‘trickster tales’ that appear in various mythologies across the world and in characters such as the Fool in King Lear. In such stories the fool, jester or trickster often uses arcane or obscure humour to impart eccentric pearls of wisdom. It is a role that Dylan himself – noted for his characteristic mixing of sly humour and his focus on transcendental concerns – has often played. In Don McLean’s potted history of rock culture American Pie he makes an appearance as …the jester… who wears …a coat he borrowed from James Dean….

IAN McKELLAN AS LEAR. SILVESTER McCOY AS THE FOOL

Jokerman is the lead track on Infidels, the first of Dylan’s ‘post-Christian’ albums. On this collection he largely abandons the preachy tone of much of his recent work. Yet he clearly still has some strong theological concerns. The song contains a number of obvious Biblical references and even appears – at least on the surface – to espouse elements of harsh Old Testament morality. But such references are leavened by the playful humour that dominates the song. It may be that Dylan is taunting his audience. He presents us with a multiplicity of images and scenarios, as if deliberately defying their inevitable attempts to figure out his actual ‘spiritual beliefs’. Or perhaps he is even teasing himself, mocking the moralistic pretensions of his recent work, and expressing his own ‘spiritual confusion’ about exactly where he stands in terms of personal beliefs.

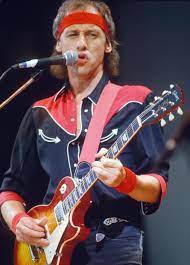

The key musical element of Jokerman is its expressive lightness of touch. This is demonstrated by its bouncy rhythm and continually cheerful and optimistic tone. The original recording uses a modified reggae beat, supplied by the legendary Jamaican rhythm section of Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare, along with producer Mark Knopfler’s distinctively ‘mellow’ guitar sound. In live performances it becomes a powerful and even danceable rock song, dominated by a fairly straightforward but evocative chorus. Above all, it revels in a new sense of freedom of thought. Dylan now sounds very happy and energised by being liberated from the rigidity of conventional beliefs. He celebrates this newly rediscovered autonomy with great verve. Much of the tone of the song takes us back to the cunningly humorous narratives of his classic 1965-66 output.

MARK KNOPFLER

Jokerman is another one of Dylan’s extended ballads – influenced, as are earlier songs like A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall and Boots of Spanish Leather – by traditional British and American folk forms. The song follows a very regular pattern of six verses of six lines each, with a standard ABABCC rhyme scheme. It has no bridge section and relies on its powerfully uplifting chorus for much of its effect: …Jokerman dance to the nightingale’s tune/ Bird fly high by the light of the moon/ Oooh ohh Jokerman!… Nightingales have appeared in many poems from Homer onwards. In ancient times they usually represented the coming of spring or of night. By the time of the Romantic poets the bird had become more generally recognised as a symbol of love. Coleridge, Milton and Blake all wrote poems addressed to nightingales. The most well known example is Keats’ profound meditation on beauty and death Ode to a Nightingale. Nightingales also appear in many popular songs, perhaps the most famous being A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square, in which the absence of the bird as a symbol of love is the central focus of the song. By this time, however, the use of the nightingale as an image had become so clichéd that it could be taken to mean almost anything. Dylan revels, as ever, in the ambiguity this produces. The ‘oohs’ in the chorus are unusual in a Dylan song, but here they are extremely effective in helping us focus on the central figure. In the verses the ‘Jokerman’ may be Jesus or the Devil, a preacher or a politician, Dylan himself or even the listener. But most of all the chorus is a joyful celebration of the freedom to ‘fly like a bird’ – and thus to think clearly and freely.

JOHN KEATS

The first verse confronts us with a series of strikingly powerful images. The initial …Standing on the water, casting your bread… immediately has Biblical connotations. The figure being addressed is, like Jesus, miraculously walking on water (Matthew 14: 21-23) and casting bread (Ecclesiastes 11:1).

We might it first think we are in for another one of Bob’s ‘sermons’. But this is immediately followed by the unforgettably graphic …while the eyes of the idol with the iron head are glowing… which sounds rather like something from a science fiction ‘B’ movie or a cheap horror film. Here there is a contrast between the sacred and the profane (or the Christian and the pagan), but it is the profane imagery which is the more striking. The fairly mundane and clichéd reference to …distant ships sailing into the mist… is followed by the dramatically visceral …You were born with a snake in both of your fists while a hurricane was blowing… The image of a figure with a snake in both fists has various mythological connotations. The Minoan ‘snake goddesses’ which were first excavated at Knossos in Crete in 1905 are representations of this image.

MINOAN SNAKE GODDESS

Snakes and serpents appear in many different contexts in the ancient texts, especially in Greek and Hindu mythologies. The line also echoes the introduction to the Rolling Stones’ 1968 single Jumpin’ Jack Flash: …I was born in a cross fire hurricane/ And I howled at the mornin’ driving rain… Jack Flash, like the Jokerman, is a possibly demonic figure who also represents the liberating power of freely expressed energy …Energy… as Blake famously put it …is eternal delight…

The reference to the hurricane also appears to anchor the song in the waters of the Caribbean, where such natural cataclysms are common. In a 1984 interview with Kurt Loader for Rolling Stone Dylan was quoted as saying that the song was written on his boat in the Caribbean and was inspired by stories of mysterious local spirits:

‘Jokerman’ kinda came to me in the islands. It’s very mystical. The shapes there, and shadows, seem to be so ancient. The song was sorta inspired by these spirits they call jumbis“.[8]

In the local Caribbean mythology of Obeah, jumbis are malevolent ghosts of those who have perpetrated evil during their lifetimes. Perhaps the Jokerman is one such ghost. Like other clowns and jokers, a Jokerman can be scary as well as funny. Here the Jokerman appears to be a figure with considerable spiritual power, who may be a mystical illustration of ancient traditions. Yet, as the last lines of the verse indicate, the limits of his power are outlined: …Freedom just around the corner for you/ But with the truth so far off, what good will it do?… This further suggests that the Jokerman is the representation of spiritual confusion – a figure who is reaching out for spiritual truth but finds that such truth is defined in so many different ways that it is impossible to really grasp. Already we learn that his powers are rather tragically limited.

CARIBBEAN FESTIVAL WITH JUMBIS

In the second verse the Jokerman becomes a rather ominous figure who only ‘rises up’ when the sun sets, suggesting that he is an emanation of the forces of darkness: …So swiftly the sun sets in the sky/ You rise up and say goodbye to no one… We are then given a warning, in epigrammatic form, of the dangers of engaging with such a ‘dark force’: …Fools rush in where angels fear to tread… is a commonly used proverbial statement first coined by the Enlightenment poet Alexander Pope in An Essay on Criticism (1709), indicating that the inexperienced may jump into dangerous situations which wiser heads might be more likely to avoid. But Dylan is not content with merely quoting the aphorism. In the next, rather convoluted line, he states that …Both of their futures so full of dread, you don’t show one… apparently indicating that neither ‘fools’ nor ‘angels’ have the answers which the Jokerman is seeking. The Jokerman himself does not even appear to have a plan for his own future. He appears to be thrashing about blindly – a spiritual seeker in the dark, perhaps – who is …shedding off one more layer of skin… (another serpentine image) and thus transforming himself into one of his many disguised forms. This is rhymed ominously with …Staying one step ahead of the persecutor within… This line is strongly resonant of religious oppression, which Dylan appears to suggest takes the form of inner guilt or sorrow that constantly destabilises the seeker of spiritual truth.

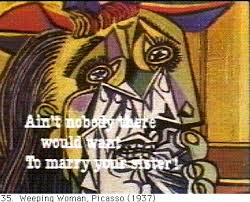

The Jokerman then transforms himself in a number of ways. In the opening lines of the third verse he seems to be a powerful supernatural being: …You’re a man of the mountains, you can walk on the clouds… (as well as the water). But he is also a …manipulator of crowds… and a …dream twister… This Jokerman may thus be a political or religious leader who ‘manipulates’ his followers, possibly in very negative ways. It is hard to interpret what comes next as anything less than sarcasm, despite its Biblical connotations …You go to Sodom and Gomorrah but what do you care?… Dylan asks. But then he spits out …Ain’t nobody there would want to marry your sister…. Here his spleen appears to be directed towards ‘false prophets’ such as TV evangelists, many of whom had been exposed as being notoriously corrupt and hypocritical. But the lines which follow: …Friend to the martyr, friend to the woman of shame/ You look into the fiery furnace, see the rich man without any name… with their clear Biblical allusions, again identify the Jokerman as a ‘Jesus figure’ who befriends those who respectable society rejects. But in doing so Dylan may also be pointing out the hypocrisy of those ‘false prophets’ who greatly enrich themselves through their broadcasts.

Some writers have claimed that Jokerman and other songs on Infidels signify a ‘return to Dylan’s Jewish roots’. This is a rather dubious assertion. Although Dylan was brought up in a Jewish family, he has never projected himself as a believer in Judaism. Biblical imagery had appeared in his early songs such as When the Ship Comes In and The Times They Are A-Changin’ and many of the songs on 1967’s John Wesley Harding album seem to imitate the tone of – and use phrases from – the King James Bible. But such imagery and references can be found throughout the entire literary canon without necessarily indicating the level of religiosity (or lack of it) of a particular writer. The use of such imagery allows poets the chance to engage with a commonly shared system of symbolism and metaphor, in order to produce multiple levels of meaning. Perhaps the strongest argument for the Judaic influence on Jokerman occurs at the beginning of the fourth verse where the protagonist is said to follow …The Book of Leviticus and Deuteronomy, two books from the Old Testament that together form the Hebrew Law or Torah. But this statement is highly qualified by the mention of …the law of the jungle and the sea… as being equally important. Thus the Jokerman is said to follow not only the strict codes of Mosaic law but also natural law; again indicating that whatever his theology he is essentially a free spirit.

In the very striking lines that follow, Dylan casts the Jokerman in a mystical light, again portraying him as a saintly or even messianic figure. We see him …in the smoke of the twilight, on a milk white steed… like the hero of folk songs such Black Jack Davy or Willie O’ Winsbury, who rides to freedom on the beautiful white horse. In Revelation 19 (11-16), the saviour himself appears on such a creature. Then we hear that …Michaelangelo indeed could have carved out your features… The use of the qualifier ‘indeed’ emphasises the perfect beauty of the figure, with an implicit comparison to Michaelangelo’s David, often seen as the most ideal representation of the human form.

MICHAELANGELO’s DAVID

The final image in the fourth verse sees our hero …Resting in the fields, far from the turbulent space/ Half-asleep ‘neath the stars with a small dog licking your face…. which recalls a famous painting by another Renaissance artist Parmigianino (1527), of Saint Rocco, the patron saint of dogs. By pointing us towards these images Dylan identifies the Jokerman with idealised Renaissance representations of beauty and serenity. This is a considerable contrast to the previous verse, where the Jokerman appeared to be especially corrupt.

SAINT ROCCO

In the final verses, however, the imagery becomes darker and more threatening, moving away from the Jokerman himself and describing the corrupt world he exists in. The third and fourth lines of the fifth verse contain the song’s most literally explosive imagery. This is framed by the pointed comparison between war makers and religious leaders, both of whom seem set on exploiting ‘the sick and the lame’. The final lines show us …false hearted judges, dying in the webs that they spin… and warn of the coming darkness: …Only a matter of time before night comes steppin’ in… The middle lines feature one of Dylan’s most distinctive collocations of imagery, full of associative half rhymes: …Nightsticks and water cannons, tear gas, padlocks/ Molotov cocktails and rocks behind every curtain… Here we see the Jokerman being engulfed by the violence of a thoroughly corrupt world. Despite his having appeared on his enchanting ‘milk white steed’ there is little indication that he has the power to sweep all this away.

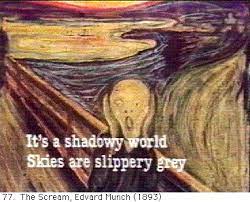

In the final verse an apparent rival to the Jokerman appears. Using imagery that is reminiscent of elements of the Book of Revelations, we are first given a description of a distinctly fallen world: …It’s a shadowy world, skies are slippery grey… We then hear that …a woman just gave birth to a prince today and dressed him in scarlet… The following lines appear to be a prophecy of the abominations that this ‘scarlet prince’ will commit when he grows up: …He’ll put the priest in his pocket, put the blade to the heat/ Take the motherless children off the street and place them at the feet of a harlot…. This rival prince (who may be identified as the ‘anti-christ’) will, it seems, control the priesthood and the military and will sacrifice the ‘motherless children’ – a phrase from a well known blues song which here appears to stand for the poor and disadvantaged in general. The ‘harlot’ may well be the Whore of Babylon, a figure in Revelations who represents all the evil in the world. It seems that the Jokerman is here being told that he will need to fight the coming of such evil, but the final lines: …Oh Jokerman, you know what he wants/ Oh Jokerman, you don’t show any response… strongly suggest that the Jokerman will be impotent in the face of this coming apocalypse.

THE WHORE OF BABYLON

Dylan’s ‘born again’ phase had begun by him experiencing what he then called a ‘personal revelation of Jesus’. He then appears to have composed almost all the songs on Slow Train Coming and Saved (as well as a number of unreleased gospel songs) in one of his sudden creative bursts. In songs such as I Believe In You, Saving Grace, Precious Angel, Pressing On and Covenant Woman he had described his personal revelatory experience. In the more political or apocalyptically oriented pieces like When You Gonna Wake Up, Slow Train Coming, When He Reurns or Are You Ready? he fused this experience with an apparent belief that the End Times were almost upon us. Some of the songs on the following Shot of Love – especially In the Summertime and Every Grain of Sand – began to express doubts about the validity of the experience. Others, like Dead Man, Dead Man and The Groom’s Still Waiting at the Altar, investigated apocalyptic themes without relying on the faith based statements of the previous albums.

Dylan’s ‘religious period’ coincided with one of the most dangerous periods of the Cold War, especially after Ronald Reagan won the Presidency in 1980 and began to build up the USA’s nuclear arsenals. In 1962 Dylan’s A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall had been a devastatingly secular response to the threat of world destruction then posed by such weapons. After his conversion Dylan began to equate this existential threat with Biblical ‘end of the world’ prophecies, especially those in the Book of Revelation. Reagan himself seemed to have made this connection, which had already been implied in statements by ‘TV preachers’ like Billy Graham and Jerry Falwell. In 1971 he had stated that …For the first time ever, everything is in place for the battle of Armageddon and the second coming of Christ… In 1983 Reagan mused that …You know, I turn back to your ancient prophecies in the Old Testament and the signs foretelling Armageddon, and I find myself wondering if we’re the generation that is going to see it come about. I don’t know if you’ve noted any of those prophecies lately, but, believe me, they certainly describe the times…

RONALD REAGAN

In many ways, Jokerman can be seen as an updated (and considerably more upbeat) version of Hard Rain, infused with Biblical quotes and references. The Jokerman, however, clearly does not have the power or inclination to prevent any future apocalypse. He is an ever-shifting, sometimes even dissolving character who may be physically present on occasions but at others appears to be a mere chimera or a product of the imagination. The song itself veers between semi-political ruminations, scary Biblical prophecies and attacks on ‘false prophets’ and other religious hypocrites. In many ways it shares the preoccupations of a song like When You Gonna Wake Up without the dogmatic shackles. Jokerman may be a ‘difficult’, highly ambiguous song but it tackles these themes with a joyous self confidence. It glories in the fact that it does not offer any obvious solutions and concludes with some searching invocations, imploring the central figure to fight his way out of a mire of spiritual confusion. It seems that our hopes for the future of the world rest with this shadowy yet magical figure, implying that we can only save our world not through faith in Jesus or other ‘saviours’ but by invoking the Jokerman – a sometimes uncertain figure representing all our human fallibilities.

A remarkable ‘lyric video’ clip was made by George Lois and Larry Sloman to publicise the song. Dylan himself features on the choruses with some rather unconvincing lip-synching but most of the video consists of images of classic artworks, from Minoan goddesses, Sumerian idols and ancient Greek and Aztec statues to Renaissance paintings by Durer, Bosch, Mantegne and Ucello; Michaelangelo’s sculptures of Moses and David, through to works by Blake, Goya, Turner, Munch and Picasso. These are interspersed with images of Dylan throughout his career, along with those of the moon landing, Reagan, the Kennedys, Martin Luther King, the cartoon Joker from Batman and an original image of Muhammad Ali with arrows in his body like Saint Sebastian. All of the song’s lyrics are presented onscreen. The phrase ‘manipulator of crowds’ is accompanied by a photo of Hitler and ‘Sodom and Gomorrah’ by a nuclear explosion. Lois and Sloman demonstrate a remarkable understanding of Dylan’s song, placing a notably contemporary political slant on its imagery. They clearly recognise that the ‘Jokerman’ is not a single person but contains aspects of all kinds of humanity. The images do not define the song but add extra potential meaning to the lyrics in a highly creative way. Dylan keeps his eyes closed during most of the choruses but finally opens them at the end before delivering one of his trademark penetrating stares.

The song was performed as the opening number at many of the gigs on the 1984 tour where it proved to be highly effective as a ‘stadium rock’ number. Since then it has been played only rarely, perhaps because it is a rather difficult song to change tempos and vocal styles for, although in a few performances from 2003 it was revived with a slower, more reflective arrangement. Covers are relatively rare, although versions by Vampire Weekend and Eliza Gilkyson add rock and folky textures respectively to the song. The first public performance of Jokerman on the David Letterman Show in 1984 (now released on The Bootleg Series’ Springtime in New York) is one of Dylan’s most renowned performances. Accompanied by a scratch band consisting of members of LA punk band The Plugz, Dylan attacks the song with raw venom, giving viewers a tantalising glimpse of what a Dylan tour with these musicians would have sounded like. Halfway through the performance, having dropped several verses, he fumbles around looking for a harmonica. When he finally finds one he stands centre stage without a guitar and blows the harp vigorously. The performance is a perfect illustration of the spontaneity of Dylan’s art at its best.

As the lead track on Infidels, Jokerman demonstrated most eloquently that Dylan was now heading into a new, post-‘Born Again’ phase of his career. His distinctive mixture of stunning ‘chains of images’ and barbed humour was certainly back with a vengeance. The figure of ‘the Jokerman’ stands with the ‘Tambourine Man’, Ramona, Johanna, The Mighty Quinn, Frankie Lee, Judas Priest and ‘The Kid’ from Subterranean Homesick Blues among Dylan’s most iconic and challenging creations. The song remains one of Dylan’s most evocative expressions of his poetic and musical power.

LINKS….

Leave a Reply