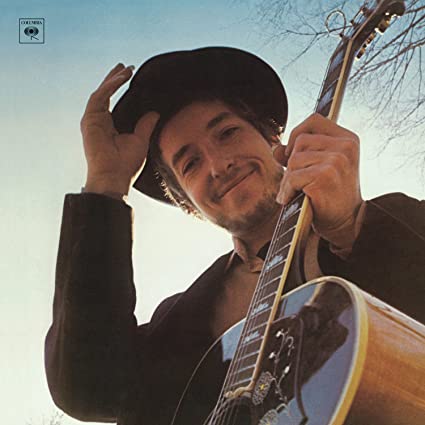

The needle hits the groove. A guitar player strums a familiar and especially resonant melodic line. It is a little hard to identify at first, as it is considerably slowed down from the deft finger picking opening of the original version. But when we hear the highly familiar opening words: …If you’re travelling to the north country fair/ Where the wind hits heavy on the borderline… we know we are listening to Girl from the North Country, one of Bob Dylan’s most memorable early love songs, based on his memories of his adolescence in the chilly ‘north country’. But at first we may wonder who this singer with the low, slightly hesitant, baritone actually is. Perhaps we can pick up the album cover and examine it again. Could it be that this guy with the enigmatic smile, who tips his cowboy hat to us, is really the ‘voice of his generation’ – the oracle of rock and roll who never gave us an easy ride with his harsh, cutting vocal style?

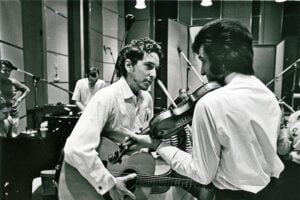

Johnny Cash and Bob Dylan in Nashville

Moments later, we are treated to the deeply resonant bass voice of Johnny Cash, a singer Dylan later described as having …a voice that came from the middle of the earth… We can just about hear Cash taking a breath before committing himself to the evocative lyrics: …See for me that her hair’s hanging down/ It curls and falls, all down her breast… hanging onto that last word, that subtly ironic use of ‘breast’ rather than ‘breasts’. As the song progresses they take a verse each, before joining together on the final chorus. This was always a piece that relied on understatement for its effects. In the original version on 1963’s Freewheelin’ the singer sounds somewhat detached from his subject, but now he and Cash give it the full emotional heft. Each verse builds up the emotional investment that both singers (who come from very different places but are united in the extreme respect they have for each others’ art) make. The performance becomes a kind of love song that they sing to each other. Whereas once it dealt in delicate remembrance, it now mines the emotional depths of the artists’ deep reverence for the power of memory itself.

To say that the opening song on 1969’s Nashville Skyline was something of a shock for many Dylan fans is in itself an understatement. Although the adoption of country stylings on much of 1967’s John Wesley Harding had to some extent prepared them, here he was utilising the full-on Nashville sound for songs which conveyed (at least on the surface) simplistic, even trite sentiments and used cliché in an unabashed way. This led many of those who viewed Dylan as a leader of the counter culture to believe that he had ‘sold out’ to commercial interests. But Dylan seemed to want to prove to the world that he could, if he turned his hand to it, write conventional romantic songs and that he had the ability to adopt a completely different voice to the ‘authentic’ one that listeners were accustomed to. But despite their brevity and straightforwardness, the songs on Nashville Skyline do not abandon poetic song writing. As Johnny Cash says in his award winning sleeve notes: …Herein is one hell of a poet…

‘IS IT ROLLING BOB?’ BOB DYLAN AND BOB JOHNSTON

Duets in Nashville

The duet with Cash was chosen from the sessions that the two singers took part in during the recording of the album. The recordings eventually became available as part of the Bootleg Series release Travelin’ Thru (2019). It has been rumoured that Bob Johnston actually arranged the sessions to coincide with Cash being in the studios, hoping that the two would get together. Their collaboration lasted only days. After running through duet versions of Dylan’s One Too Many Mornings and Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right and Cash’s I Still Miss Someone with the studio band on the first day, the two reconvened for another long day of takes with Cash’s band, which included rockabilly legend Carl Perkins on guitar. Thirty eight tracks were recorded, presumably leaving almost no time for rehearsals. Dylan and Cash were clearly relying on their previous shared knowledge of the songs, most of which were from Cash’s repertoire. The two are clearly enjoying themselves, even if the renditions of Cash’s songs like Big River, Five Feet High and Rising, I Walk the Line and Ring of Fire are somewhat ragged. The duets also incorporate a couple of medleys of Jimmie Rodgers’ best known tunes, along with Mystery Train and That’s All Right Mama from Elvis’ Sun Sessions and a few traditional numbers and hymns. Only Girl from the North Country and One Too Many Mornings appeared to have been seriously worked on for possible inclusion on the album. The use of the Girl from the North Country duet to open the album was a clear attempt by Dylan to promote the virtues of a key genre of American music for an audience that had previously rejected it as being too conservative.

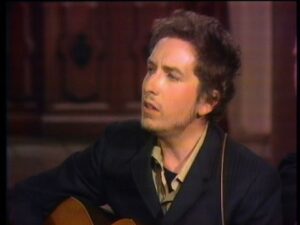

BOB AND JOHNNY ON THE ‘JOHNNY CASH SHOW’ 1969

Wanted Man

The one new song that came out of the Dylan-Cash sessions was Wanted Man, a humorous travelogue in which the singers take great delight in reeling off a list of American place names while recounting the adventures of an outlaw who appears to have escaped both the law and the attentions of various rather colourfully named (and presumably abandoned) women like ‘Nellie Johnson’ and ‘Jeanie Brown’. The song is a humorous update of Dylan’s earlier unrecorded Rambling, Gambling Willie, which eulogised a rather heroic outlaw figure, as well as I’ve Been Everywhere, a humorous song that was a hit for Hank Snow in 1962 and which also lists American place names. Dylan and Cash appear to greatly enjoy pushing the limits of what they can get away with here. It also appears as the first song in Cash’s momentous and defiantly anti-establishment performance at San Quentin prison, which was filmed for a TV special and commemorated by the release of a soundtrack album. The raucous and highly volatile prison audience seems to get the joke. A very different version was recorded by Nick Cave on The Firstborn is Dead (1985), which begins with Dylan’s lyrics and then expands on them (as the song appears to invite interpreters to do). Cave’s ‘wanted man’ is, however, a very scary and genuinely dangerous figure, as conveyed through his increasingly deranged rant as the tune builds up.

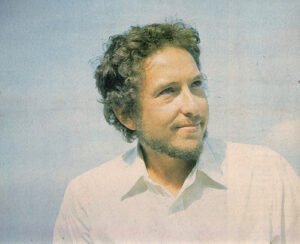

DYLAN IN THE NASHVILLE STUDIOS

Following advice from producer Bob Johnston, Dylan had begun recording in Nashville – the ‘capital of country music’ – in 1966 during the Blonde on Blonde Sessions. After his motorcycle accident and a year spent making secret recordings with members of The Band, he again travelled to the city to record John Wesley Harding. Dylan is notoriously fond of creating spontaneous art and is known to have little regard for studio ‘trickery’. He even made disparaging remarks about The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper album, which he regarded as relying too much on sound effects and production techniques. In this context, the famously ‘hands off’ Johnston was his ideal producer at the time. Dylan found the highly experienced studio session musicians who worked in the Nashville studios to be ideal for his own recording methods. Prominent among them were Kenny Buttrey (drums), Pete Blake (pedal steel) and Charlie McCoy (guitar and harmonica), who had all backed Dylan on John Wesley Harding, along with Charlie Daniels (bass), Bob Wilson (keyboards), Fred Carter and Norman Blake (guitars). With their great experience of backing so many artists and playing so many different styles of music, they were capable of picking up his musical ideas very quickly and of supplying the kind of spontaneously inspired playing which Dylan required. If he inspired them, they also seem to have inspired him, as many of the songs on the album were written in the studio.

Nashville Skyline has often been labelled a ‘country’ album. However, that label may be more connected with the type of playing the musicians supply than the songs themselves. Although country music certainly contains much ‘schmaltzy’ material, the kind of country that Dylan himself admired (and which had clearly already influenced his own song writing) often tended to veer towards harsh emotional realism. Hank Williams, who in 1963’s Poem for Joanie Dylan had identified as his ‘first hero’, achieved his fame with songs such as I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry, Your Cheatin’ Heart and Cold, Cold Heart that focused unapologetically on his own existential pain. Dylan’s favourite Johnny Cash songs were his early Sun Studios recordings, which were often stark and bitter testaments. Folsom Prison Blues (a version of which Dylan recorded for the Self Portrait sessions), with its famously amoral line …I shot a man in Reno, just to watch him die… takes us inside the mind of a callous murderer. Hank Snow’s 99 Miles Down a Dead End Street (which Dylan recorded in 1988) was a no-holds-barred depiction of the breakdown of a relationship. Even Willie Nelson’s Crazy, which became a major hit for Patsy Cline, was a song of despair from the point of view of an abject lover. But Nashville Skyline, despite containing several laments for lost love, differs from Dylan’s previous works in that its overall feel is decidedly buoyant and cheerful. The album creates an optimistic mood from the moment that Girl from the North Country segues into the catchy and upbeat bluegrass instrumental Nashville Skyline Rag. From there on, the positive vibe is maintained up until the triumphant Tonight I’ll Be Staying Here with You.

It would certainly not be true that Dylan created ‘country rock’ single handedly. Country music, with its roots in the white culture of the Deep South, was regarded by many members of the ‘alternative society’ as a reactionary or ‘square’ form. But a number of musicians who had grown up with this music, but who were also very much part of the ‘hippie generation’, were determined to show that it had its own unique strengths. By the time Nashville Skyline was recorded, what is now known as ‘alt country,’ was already established. The Band’s groundbreaking first album Music from Big Pink (1968) had a profound country influence. Even West Coast psychedelic bands like the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane were experimenting with country styles. Also, despite the racial divide that saw the emergence of separate sales charts for ‘white’ and ‘black’ music, country music itself was deeply influenced by the musical structures and language of the blues. So it was not really that far removed from rock and roll. Indeed, many of the early rock and roll pioneers, such as Jerry Lee Lewis, Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins and Bill Haley, also recorded much ‘straight country’ material. Their strand of rock and roll was known as ‘rockabilly’, a form which – despite the presence of the Nashville musicians – the songs on Nashville Skyline can be most usefully compared.

The visionary figure who was determined to change the prevailing view of country music was the extraordinarily talented yet tragically self destructive Gram Parsons. When Parsons joined The Byrds in 1968 he inspired them to record the explicitly ‘countrified’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo, which included such ‘redneck’ anthems as The Christian Life as well as a steel-guitar drenched reading of Dylan’s You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere. By 1969 Parsons had formed his own band, the Flying Burrito Brothers, whose first album The Gilded Palace of Sin, used many stylistic elements of ‘pure’ country, often in a rather twistedly ironic way. The track that epitomised this most was the closer, Hippie Boy, which used the country sub genre of the spoken voiceover (popularised by Hank Williams under his pseudonym ‘Luke the Drifter’ which was generally a vehicle for delivering moral or religious homilies) to relate a subversively hilarious tale of a young hippie who becomes a ‘drug mule’. Unlike Parsons, Dylan seemed to be less interested in exploring the various lyrical conventions of country music than in creating apparently straightforward songs which – as the various versions which appeared over the years have demonstrated – could easily be adapted into other musical formats.

After the sprightly instrumental, Dylan is heard to utter the (by now ‘immortal’) words …Is it rolling, Bob?… which one presumes is him asking his producer if the tapes are ready to go. The phrase also works to kick in the eight original songs that follow in quick succession. ‘Bob’ himself is certainly rolling now. To Be Alone with You is a joyous confection whose narrator simply elaborates on the title phrase. He simply wishes to hold his lover …tight, the whole night through… Dylan claimed to have written the song for Jerry Lee Lewis and it certainly has the ‘rollicking’ feel of many of Lewis’ more country flavoured recordings such as Chantilly Lace or Crazy Arms. The musicians hit a disciplined groove, with delicate snatches of guitar counter posed against prominent bass and some distinctive piano runs. The lyrics are extremely minimal, stripped of any concrete poetic imagery: …To be alone with you/ Just you and me/ Now let me tell you true/ Ain’t that the way it ought to be…. In the following verse he expresses the desire to …be alone with you/ At the close of the day/ With only you in view/ As evening slips away… Then there is almost a philosophical twist: …It only goes to show/ That while life’s pleasures be few/ The only one I know/ Is to be alone with you…. All specific detail has been cleared away and the rhyme scheme is pointedly basic.

Here, and in a number of the other songs, the main lyrical influence may well be Buddy Holly, whose dexterous and highly memorable compositions had a great effect in Dylan, The Beatles and many others. One of Holly’s best known songs Not Fade Away (recorded as a single by The Rolling Stones in 1964 and later often performed on stage by The Grateful Dead and Dylan himself, has a similar, ultra-basic lyric: …I’m gonna tell ya how it’s gonna be/ You’re gonna give your love to me/ I’m gonna love ya night and day/ Love is love, not fade away… Despite this, it is undoubtedly a song with great resonance and rhythmic power.

To Be Alone with You, like most of the songs on the album, features a bridge section, a conventional feature of pop song writing which rarely appears in folk and blues material. Many country classics, like Cash’s I Walk the Line or Dolly Parton’s Jolene, also eschew this ‘sweetening’ device. Dylan uses the bridge to contrast the blandness of the verses with some clever lyrical dexterity. He begins by trotting out a well worn blues cliché: …They say that night time is the right time… (also the title of a Ray Charles hit) … To be with the one you love… Then he throws the tongue twisting, internally rhyming lines: …Too many thoughts get in the way in the day/ But you’re always what I’m thinking of… which take us helter skelter into the final verse, which conveys more simply expressed longing. Finally the narrator, identifying himself as a ‘regular’ blue collar worker (and thus an ‘ordinary guy’) says he will …thank the Lord/ When my working day’s through… The ‘sweet reward’ he tells us that he will receive is unlikely, however, to be a spiritual one. Another feature of the Nashville songs which differs from most country material is their (sometimes implied) sexual explicitness. In this sense the song is closer to a pop song like The Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night than to most country songs, which – although they may be concerned with matters such as divorce or the effects of alcoholism on marriages – very rarely actually take us into the bedroom. There is no doubt here why Dylan’s narrator wants to be alone with the subject of the song. All in all, it is the sort of material that the notoriously lascivious Jerry Lee would have lapped up…

Perhaps surprisingly for one of Dylan’s slighter songs, To Be Alone with You has turned out to have a long performing history, although this did not begin for some twenty years after it was recorded. During the Never Ending Tour, Dylan often interspersed the Nashville songs into his sets, perhaps to provide a little light relief from the intensity of much of his other material. At the Tower Theater, Philadelphia on 15th October 1989, now accompanied by a punky three piece band, he opened the show with a raucous, speeded up rockabilly version, duelling guitars with G.E. Smith. He played the song over a hundred times between 1989 and 2019, mostly as a set opener – a kind of jokily meta textual welcome to the audience he was about ‘to be alone’ with. After he switched from guitar to keyboards onstage in 2003, it appeared in set lists even more frequently. He could now indulge his ‘inner Jerry Lee’ in splendidly enjoyable style.

In 2021, in Dylan’s TV ‘pandemic special’ Shadow Kingdom, the song was almost completely rewritten, with the backing now re-imagined as a Tex Mex shuffle dominated by accordion and acoustic guitar. Only the title phrase and a couple of other lines remain from the original, making this practically a new song. ..To be alone with you… Dylan begins, relishing the first of the new clichés he is about to deliver …Just you and I/ Under the moon/ In the star-spangled sky… Then he declares, rather dramatically …I know you’re alive/ And I am too/ My one desire/ Is to be alone with you… What follows is a playful reconstruction of the song. Now he begs the object of the song to allow him …just an hour/ In a castle high, in an ivory tower.. . He becomes increasingly obsessional, with …I wish the night was here… now being followed by … Make me scream and shout/ I’d fall into your arms/ Let it all hang out…. This becomes rather disturbing when he declares that, in order to be alone with her, he will ‘hound her to death’.

The song now seems to have acquired the kind of sinister narrative subtext which Dylan had injected into such ‘romantic’ songs as Moonlight and Bye and Bye (both 2001). In the final verse, in an apparent attempt to overcome his confusion, he tells us that …I’m collecting my thoughts in a pattern/ Movin’ from place to place/ Steppin’ out into the dark night/ Steppin’ out into space… He now begins to wonder if perhaps he has actually carried out the threat he made previously. …Did I kill someone… he asks …Did I escape the law?… Despite these dark intimations, the lively pace and light musical touches suggest that we should not take all this entirely seriously. This is emphasised by the lines …Got my heart in my mouth/ My eyes are still blue… The second line is a knowing quotation from Hank Williams’ similarly self deprecating Why Don’t You Love Me Like You Used To Do?... Finally he asserts that his goal is to achieve ‘mortal bliss’. But there is nothing ‘spiritual’ about the song. The new version, which has continued to be a staple of the set throughout the Rough and Rowdy Ways tour since 2021, is a playful projection of the original, taking us into darker territory. But Dylan still has his tongue firmly in his cheek.

Leave a Reply