Cavett: … What was the controversy about the National Anthem and the way

you played it?

Hendrix: I don’t know, man. All I did was play it, I’m American, so I played it.

I used to have to sing it in school; they made me sing it in school. So it’s

a flashback. I don’t know what else about it…

Cavett: When you mention the National Anthem and talk about playing it in any

unorthodox way, you immediately get a guaranteed percentage of hate mail

from people who say, “How dare anyone”.

Hendrix: That’s not unorthodox. That’s not unorthodox. I thought it was

beautiful. But then there you go.

Cavett: Don’t you find there’s a certain mad beauty in unorthodoxy?

Jimi Hendrix interview on the Dick Cavett TV Show, 1970

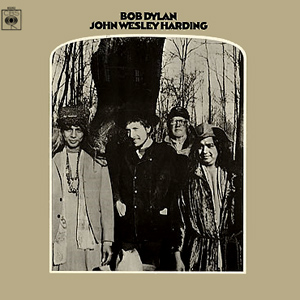

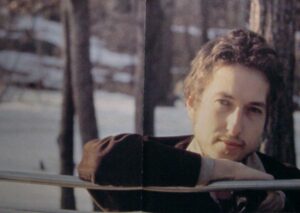

All Along the Watchtower is one of Bob Dylan’s most celebrated songs. It holds the record for performances, with Dylan having played it over 2,000 times; often as an encore or closing number. In writing the songs for John Wesley Harding, on which the song first appeared in late 1967, Dylan demonstrated his ability to write short, suggestive lyrics. Watchtower is a prime example of this, consisting only of three verses of four lines each. Yet it has an epic scope and has been subject to multiple interpretations. This effect is largely achieved by the way Dylan – as he does in a number of songs on the album – seamlessly mixes modern colloquial language with archaic and Biblical terminology.

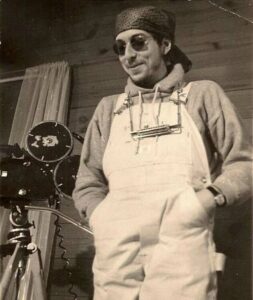

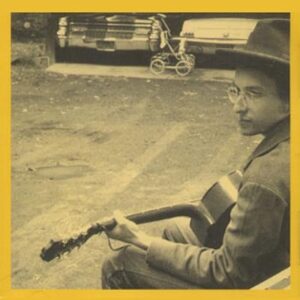

The musical structure of the original recording is simplicity personified. The acoustic guitar plays a repeated haunting riff backed by bass and drums. Dylan’s harmonica fills in the gaps between verses and ends the recording. The entire song is only two and a half minutes long. Jimi Hendrix’s brilliant cover version, released just a few months later, lifts it onto another level, punctuating the verses with inspired guitar passages that supply a musical interpretation of the implications of the lyrics, so creating a bona fide rock classic on which the many cover versions which have followed have been based. When Dylan himself began performing the song on a regular basis, he himself used Hendrix’s version as a model.

Hendrix was, of course, the most talented and imaginative guitarist in rock music history. The genius of his interpretation of the song was that he somehow appeared to understand the apocalyptic implications of the lyrics on a visceral level and was able to express them perfectly through the mastery of his instrument. In his take on the song, as well as in much of his other material, he gave voice to the fear of nuclear extinction that hung like a dark cloud over the 1960s in the wake of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Hendrix himself had briefly served in Vietnam and it is no surprise that the music he made in his brief career from 1966-70 is often associated with the war to which so many anti-establishment groups in the USA and across the world were so vehemently opposed.

Like all black people in the USA, Hendrix had also experienced the racism of the age which Civil Rights protestors had fought so hard against. The beauty and majesty of his guitar playing, with his extensive and uniquely imaginative use of echo and reverb, somehow suggests the violence of the age but tempers this with a dark, unknowable beauty and an aching for a sweeter, fairer world. Never has melody and musical distortion been fused so effectively, in a style which epitomises years of cultural ferment with stunning eloquence. To argue that All Along the Watchtower is ‘about’ Vietnam or the Cold War is to reduce its suggestive lyrical power. But the consciousness of these elements is a feature of all Hendrix’s music. In this song he found the perfect vehicle to express the hopes and fears of his audience.

The first two verses of the song consist of a conversation between two figures who are identified only as ‘the joker’ and ‘the thief’. Jokers (or jesters, or fools) and thieves are stock characters in the Bible, Shakespeare and much of the entire Western literary canon. Dylan’s lyrical restraint here pares down their exchanges so that what they say appears to have tremendous resonance and suggestive power. It is not until the third verse, which Christopher Ricks and others have argued persuasively is the ‘real’ opening of the song, that any physical or historical context for the conversation is suggested. The Joker’s desperation in the first verse is tempered by the thief’s more relaxed attitude in the second verse. They appear to be suggesting different ways to deal with a very threatening situation.

Ironically it is the Thief, rather than the joker, who has a more light hearted attitude. The figure of the Joker, most famously epitomised by King Lear’s ‘wise fool’, is traditionally portrayed as both a trickster and a truth teller – the only one who can honestly express the reality of a situation. Such is the role of satirical comedians even to this day. But here the Joker gives a decidedly sober account of the crisis that he, and presumably his whole world, is up against. The song begins …”There must be some way out of here” said the Joker to the Thief…./ There’s too much confusion, I can’t get no relief”… words which perfectly summarise not only the claustrophobic cultural context of the late 1960s but the entire existential crisis which is about to unfold.

The Joker then piles up evidence of oppressive forces that are plaguing him: …Businessmen, they drink my wine, plowmen dig my earth/ None of them along the line know what any of it is worth… Not a word is wasted here. The contrast between the contemporary sounding ‘businessmen’ and the medieval ‘plowmen’ is immediately noticeable, placing the action of the song in a highly ambiguous historical context. The reference to ‘businessmen’ suggests that the Joker has been exploited by those who prize material gain above all while the ‘plowmen’ appear to be ‘digging’ into his very soul. Dylan’s use of the terms ‘wine’ and ‘earth’ here have a particular resonance. The line could perhaps have read ‘drink up my blood’, as in Stuck Inside of Mobile whose ‘railroad men’ are said to …drink up my blood like wine…

The blood/wine catechism is central to the Roman Catholic mass in which the wine that supplicants taste is meant to be transmogrified into their saviour’s blood. It seems that the representatives of material greed are ‘drinking’ his very life blood. The Joker may be speaking for all humanity, whose planet is being ravaged by the ‘plowmen’ – perhaps symbolising the spiritual and existential ‘extraction’ of its ‘life blood’. It is suggested that both the ‘businessmen’ and the ‘plowmen’ are draining away the Joker’s humanity – and therefore that of all of us. The final line of the verse strongly suggests that both businessmen and plowmen are spiritually bereft, without any understanding of the damage they are causing.

The Thief is another literary archetype, who may be a figure of liberation like Robin Hood or Aladdin or an evil trickster like Loki in Norse mythology, who is constantly scheming to undermine his opponents. In Tears of Rage, one of the as yet unreleased Basement Tapes which Dylan had recently written, the anguished chorus ends with …Why must I always be the thief?…. The thief of fire is a common mythical archetype in many cultures as an explanation of how humans have appropriated physical power over nature – the Greek hero Prometheus being perhaps the most well known. The Thief of Fire is a character who does not always handle this responsibility well. Robert Oppenheimer, the ‘inventor’ of the atomic bomb, was characterised by this phrase on more than one occasion.

Dylan’s thief certainly appears to be a trickster. He begins by ‘kindly’ reassuring the Joker that there is …No reason to get excited… because …There are many here among us that feel that life is just a joke… Here the thief cleverly manoeuvres himself onto the Joker’s home territory. Perhaps he is worming himself into the Joker’s affections. But he soon makes clear that whatever situation they are facing is ‘beyond a joke’. …You and I… he tells him, maintaining his friendly facade …We’ve been through that, and this is not our fate… The colloquial phrase ‘We’ve been through that’ is a decidedly modern one, suggesting shared psychological experience. It could be that the Thief is merely being sympathetic but he may also be secretly trying to gain the Joker’s confidence.

The Thief’s entreaties are followed by one of the song’s most chilling lines, as his blandishments suddenly turn towards a dark reality. …Let us not talk falsely now… he tells the Joker …The hour is getting late… This is of course a very simple statement which can be interpreted in many ways. We might imagine that the two figures have a mission to complete and that the Thief is reminding his companion of this. On the other hand, the implication may be that the philosophical discussion they have been having may soon be entirely irrelevant. At this point Hendrix launches into an extraordinary guitar solo, juggling two instrumental themes, with the music building and building in intensity to suggest an apocalyptic conflagration.

It is only in the final verse, as we switch to a third person narrative, that the conversation appears to be placed in any physical situation. But even this is highly ambiguous. Although this might well arguably be the ‘real first verse’ of the song, it is crucial that it is placed here as it works very much like a cinematic flash back. Dylan merely draws ‘pencil outlines’ of the scene, leaving us to fill in the rest. …All along the watchtower… the narrator tells us …princes kept the view/ While all the women came and went, barefoot servants too… The phrase ‘all along the watchtower’ is of course ungrammatical. The word ‘along’ would normally only apply to a series of ‘watchtowers’. But here a kind of magical transformation takes place. The ‘watchtower’ now becomes more than just a single ‘dark tower’ but a physically unlimited instrument for surveillance of us all – the conscience, perhaps, of the world. The lines about the ‘women who came and went’ have been compared by Michael Gray to the lines in T.S. Eliot’s existential nightmare The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock which run …In the room the women come and go/Talking of Michelangelo..

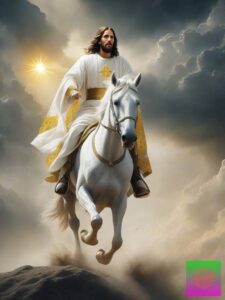

The presence of the watchtower has Biblical conations which can be strongly associated with the themes of the song. In Isiah 21 the Old Testament prophet instructs his followers to ...Prepare the table, watch in the watchtower, eat, drink: arise, ye princes, and anoint the shield. For thus have the Lord said unto me “Go set a watchman, let him declare what he seeth”/ And he saw a chariot with a couple of horsemen, a chariot of asses, and a chariot of camels….The watchman answers: …Babylon is fallen, is fallen; and all the graven images of her gods he hath broken unto the ground… Here we meet the princes mentioned earlier, who have taken on the role of watchmen. ‘A couple of horsemen’ are also mentioned. Perhaps these are the Joker and the Thief. The declaration that ‘Babylon has fallen’ has decidedly apocalyptic connotations and is often taken as a prelude to the final conflagration in the Book of Revelations, which signals the end of the world and the coming of the Millenium, the ‘thousand years of peace’ which is only achieved by mass slaughter on an unimaginable scale. The parallels with nuclear war have often been drawn. In the Bible Babylon is the place of captivity of the Israelites and thus an epitome of all the evil in the world.

The final lines of the song, with all their suggestive menace, certainly suggest that the ‘Babylon’ of our contemporary world is about to fall: …Outside in the distance, a wild cat did growl/ Two riders were approaching. The wind began to howl… The ‘wild cat’ may represent untamed nature, complaining about human interference. We are not told whether the two riders are in fact the Joker and the Thief, although if this verse really is a flashback the lines are describing their appearance before the conversation has been held. On the other hand, perhaps these are two additional riders who will, along with the Joker and the Thief, make up the numbers of the the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse – Death, Famine, War and Conquest – whose arrival will signal the arrival of the ‘end times’. It is also possible to interpret these lines in an entirely secular way, or just to drink in their suggestive power. Something major, it seems, is about to happen. But Dylan does not make it clear what the outcome will be. Just as we are forced towards much conjecture about the meaning of the song and its historical and geographical context, so we are left to imagine what this howling wind will bring. Perhaps it really will be the end of the world. Or perhaps this will be a wind of positive change, of a revolution of consciousness that will save the world.

Dylan wisely leaves those details, and those conclusions, to us. Having set up a dialogue to consider nothing less than the meaning of life itself, he leaves us to figure the solution out ourselves. Is life (and not just individual lives but the lives of all humanity) really just a ‘joke’? Or is it far more important and precious than this? All Along the Watchtower is a masterful concoction of extreme opaque symbolism, mixed with dark prophecies. But rather than merely allowing us to imagine an orgy of mindless destruction, as in a sensational Godzilla movie or the Book of Revelation itself, the openness of the symbolism it uses creates a space in which we can imagine that, although our civilization might appear to be doomed, another future is possible. In Dylan’s original version the final short harmonica solo trails off quickly, leaving us to contemplate our actions and our choices. Yeats’ great poem The Second Coming ends with a ‘terrible beauty’ being born into the world. In Hendrix’s version of All Along the Watchtower the guitar now spirals off into the infinite distance until it finally fades away, suggesting that, despite the fact that we may be at the edge of destruction, a new kind of beauty which is beyond terror is already being born.

Leave a Reply