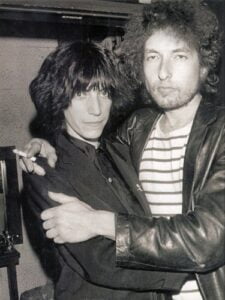

DYLAN AT THE OTHER END 1975: not wearing a disguise for Abandoned Love

3rd July 1975: The Other End (formerly known as The Bitter End), Bleecker Street, Greenwich Village. Tonight the two hundred or so punters in this famous coffee shop and folk music venue are in for quite a surprise. Most of them can hardly believe their eyes when they see who is on stage. For the first two songs, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott sings and plays guitar on Woody Guthrie’s Pretty Boy Floyd and the old blues nugget How Long, How Long. It’s no surprise to see Ramblin’ Jack. His style and repertoire has changed little since he first made a name here in the late 1950s and he has made many appearances in Greenwich Village in the intervening years. Bob Dylan, however – who is quite nattily attired in a hooped tee shirt and a black leather jacket – and who is now accompanying Ramblin’ Jack on second guitar and occasional, rather uncertain, backing vocals, has not appeared in the Village since his early pre-global-fame days. Apart from a brief gig with Neil Young at a Benefit concert in San Francisco in March, he has not been seen in public since the end of his Arena Tour with The Band in early 1974. Since then he has written and recorded the astounding Blood on the Tracks, his first great ‘comeback’ album.

DYLAN WITH PATTI SMITH

Abandoned Love differs considerably from the songs on Blood on the Tracks, which are heavily coded and delivered through a range of different personas, sometimes even within the same song. This is a first person narrative which takes us into the narrator’s inner consciousness and which deals with the effects of a broken relationship with a dreamy detachment, sometimes spilling into rather bizarre touches of humour. The narrator continues to insist on his overwhelming love for the woman in question but his mind tends to wander off in odd directions. Although this is a ‘break up’ song, the narrator does not expect us to feel sorry for him. It is almost as if Dylan is using the song to interrogate the very process of writing about such feelings.

The first couplet is immediately arresting: …I can’t hear the turning of the key/ I’ve been deceived by the clown inside of me… The image of a clown as a kind of internal impish spirit is a very Dylanesque conceit. He has long been fascinated by circuses (as seen in songs like Dusty Old Fairgrounds and Ballad of a Thin Man) and his own writing has always been informed by his ability to add a humorous slant to almost any subject. But clowns can, of course, be scary as well as funny, as revealed in Hollywood horror movies like Poltergeist (1982), It (1990) and Joker (2019). In the studio version the first line is changed to …I can see the turning of the key… which implies a greater self awareness of the internal process being described. Right now, though, he is in the dark, and is thus very vulnerable. Then we hear that …I thought that he was righteous but he’s vain… The use of the term ‘righteous’, which normally tends to be associated with religious morality, seems somewhat out of place here, but certainly represents the narrator looking inside himself and discovering his own insecurities. We do not hear about the clown again, but his presence can be felt throughout the song. He is always niggling at the narrator and, like Lear’s fool, makes him question his own feelings and motivations. The final line …Something’s telling me I wear the ball and chain… suggests that the narrator is ‘imprisoned’ within his own mind, perhaps by this malicious ‘joker

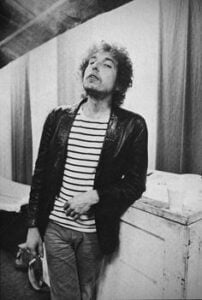

DYLAN BACKSTAGE

The next verse is a supreme example of Dylan’s unique ability to mingle highly ambiguous poetic imagery with colloquial asides. It begins: …My patron saint is fighting with a ghost/ He’s always off somewhere when I need him most… These lines seem to show the narrator cursing his own luck, symbolised by the (frequently absent) ‘patron saint’. The saint should be protecting his mental health, but the ghosts of the past are preventing him doing so. The next two lines work in a similar way: …The Spanish moon is rising on the hill/ But my heart is telling me I love you still… A ‘Spanish moon’ is a name for a phase of the moon that provides a particularly bright means of illumination. It should thus be clear to the narrator that his love is hopeless, but his heart is clearly telling him the opposite. Dylan sets up the tension between the feelings of the heart and logical sense quite brilliantly here. He then tells us that he ‘returns to town’ with a ‘flaming moon’ – no longer just bright, but on fire. This appears to represent the fact that his obsessive passion is now getting dangerously out of control. This is clearly demonstrated when he glimpses the woman in the street and …begins to swoon… We then switch to a rather uncomfortable intimate revelation: …I love to see you dress before the mirror… The narrator is clearly having erotic thoughts now. Dylan, as he does on other occasions, pronounces ‘mirror’ as ‘meeeeer’ in order to facilitate the next rhyme. He stretches out the final line like a blues singer in full ironic mode: …Won’t you let me in your room one time before I disappear… He is manifesting here more as the ghost than the clown. But the appeal he is making to her is clearly futile.

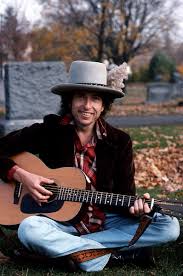

Over the next two verses, the focus moves away from the woman and becomes increasingly internalised. Verse three begins with two of Dylan’s most quotable lines: …Everybody’s wearing a disguise/ To hide what they’ve got left behind their eyes… but when he refers to ‘everybody’ it seems that he may really be talking about himself. The whole song is concerned with what he has ‘got left behind his eyes’ – all the hidden psychological strains that a creative artist has to bear, especially when in a relationship. But the narrator admits that …Me, I can’t cover what I am… This is quite an admission for a poet who (as Joan Baez so memorably puts in it in her Diamonds and Rust) is …so good with words/ And at keeping things vague… The line which follows this …Wherever the children go, I’ll follow them… is perhaps the most mysterious in the song. The narrator seems to want to follow a path of innocence that is barred to him. But this is made clearer in the next verse, in which he now begins to rail against external forces: …I can’t play the game no more, I can’t abide/ By their stupid rules that kept me sick inside… Although he wants to embrace his ‘inner child’ this is clearly no longer possible as he feels hidebound by the ‘stupid rules’ of society’s strictures. He describes these rules very memorably as having been ...made by men who’ve given up the search/ Whose gods are dead and whose queens are in the church… This rather surprising but highly distinctive rhyme takes the form of a scathing aside directed at those who have abandoned the quest for spiritual fulfilment, which to Dylan is identical to poetic inspiration. The reference to the queens being ‘in the church’ seems to imply that they are buried in such a building and are therefore as dead as the redundant gods which the unnamed ‘they’ are following.

What follows is supposedly a direct address to the woman, but again the narrator is really more concerned with himself. In a beautifully expressed logical paradox Dylan explains that …I march in the parade of liberty/ But as long as I love you I’m not free… Liberty parades are a particularly American institution; the most well known being held on the Fourth of July (American Independence Day). Here Dylan links the inner state of mind of the narrator with the context of American public institutions, showing the contrast between external show and real inner feelings. To the narrator, the ‘parade of liberty’ represents his own striving for freedom; the implication being that being trapped in this relationship is destroying his ability to be truly creative. In the next lines he appears to be addressing the woman directly, really playing the victim now …How long must I suffer such abuse?… he cries, although he does not sound in any way in pain. The whole song is delivered in a tone of light irony, which is encapsulated in another extended denouement: …Won’t you let me see you smile before I cut you loose?… Of course, he is hardly likely to see her smile if he has just accused her of ‘abuse’. He appears to be desperately requesting one last encounter with her. But one must ask at this point as to whether he is addressing a real woman or his artistic muse. The narrator seems to think that his powers of expression have diminished but that if he is given ‘one more chance’, perhaps they will return.

DYLAN IN THE STUDIO

The penultimate verse features more weird juxtapositions. It begins with the instruction …Send out for St. John the Evangelist!… but it seems as if this is actually a suggestion by one of the narrator’s friends, who are clearly being of no help to him at all. He confides in us that … All my friends are drunk/ They can be dismissed… St. John is reputed to be the author of The Book of Revelations, but the narrator will not be receiving any meaningful revelations now. He has to rely on himself but does not find this easy. …My head says that it’s time to make a change… he tells us, but then he confesses that ….My heart is telling me I love you but you’re strange… Here the contrasting roles of ‘head’ and ‘heart’ – which can perhaps be identified with the ‘patron saint’ and ‘ghost’ respectively – are emphasised. When he delivers this line, we can hear some members of the audience burst out into slightly nervous laughter. This line is clearly funny, but they do not seem sure that they should really laugh. Finally he makes one last appeal to his love object, asking her to get dressed up for him with her ‘heavy makeup and her shawl’. With considerable sarcasm he asks her if she will …descend from the throne… she is sitting on. Then, finally, we get the song title: …Let me feel your love one time before I abandon it…

Abandoned Love projects a very unusual perspective onto the model of the love song. The narrator appears determined to ‘abandon’ the woman but in reality his ‘heart’ is telling him he cannot do this. The song dramatises the inner struggle that a poet like Dylan, who relies on quick bursts of inspiration to function, will inevitably face when he attempts to ‘move on’ towards new types of inspiration. Something, it seems, will keep drawing him back into the same old inner conflicts. But ultimately this narrator’s ‘love’ for poetic inspiration cannot be abandoned. It can be argued that Abandoned Love is a highly imagistic and imaginative depiction of the inner process that Dylan – whose real life marriage was then in the process of disintegrating – had to put himself through in order to create the cathartic songs on Blood on the Tracks. Only by drawing on the feelings of intense pain that his personal situation presented him with could he begin to reclaim his contact with the muse that had supplied him with such powerful leaps of the imagination in his earlier career. But the tone of Abandoned Love, which is never depressing and often quite light hearted, suggests that this inner conflict has been resolved. He knows that he must move on from being entrapped in a situation in which his inspiration is blocked but he yearns for one more experience of the pleasure that being in the relationship gives him. Thus the song dramatises the eternal dilemma of the artist, who may need to reject the pleasure that love and companionship offers in order to preserve his artistic freedom. His love for individual women may come and go but his relationship with his artistic muse can never be truly ‘abandoned’.

LINKS…

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

THE CAMBRIDGE BOB DYLAN SOCIETY

Leave a Reply