…I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal…

Martin Luther King, Speech at the March on Washington, 28th August 1963

You sound like a Hillbilly,

We want folk singers here!

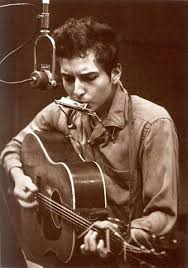

Bob Dylan, Talkin’ New York (1963)

DYLAN AND PROTEST

Bob Dylan arrived in the bohemian oasis of Greenwich Village at the age of nineteen in 1961, determined to make his name as a folk performer. He had already absorbed the influence of a whole range of American ‘roots’ music – including the blues, gospel, country, bluegrass and Appalachian folk. But it was as a ‘protest singer’ – a composer of songs that attempted to expose the corruption, inequality, racism and ‘flag waving’ militarism of American society – that he first achieved significant fame. Amid the conventionality of 1950s and early 1960s American society, the Village had a developed a reputation as a Mecca for non-conformists and social activists. It was home to a nascent counter cultural movement which took its lead from radically hedonistic Beat poets and writers like Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac. The time of Dylan’s arrival also coincided with the rise to prominence of the Civil Rights movement and the growing international tensions which threatened to bring the Cold War to a terrifying apocalyptic climax. It did not take him long to take up the mantle of his hero Woody Guthrie as a social and political commentator.

DYLAN AT THE MARCH FOR FREEDOM 1963

PROTEST SONGS

Between 1961 and 1963 Dylan poured out around a hundred songs, many of them ‘topical’. Encouraged by his girlfriend Suze Rotolo, who was involved in various political groups, scouring newspaper reports for suitable topics. He had also become an avid consumer of poetry, rapidly absorbing much of the canon of American, French and British poets. Displaying an incredible intellectual energy for one so young, he was able to synthesise both the radical and the conservative elements of Village culture in a way that no other contemporary folk singer could match. As a keen practitioner of the ‘folk process’, virtually all of Dylan’s ‘protest songs’ rested on melodies that had been adapted from traditional or well known tunes. Following the example of Guthrie’s best known works, the focus is always on communicating a strong political or social message. The ‘voice’ of the narrators is usually that of Dylan himself. He usually adopted what sounded to those unfamiliar with folk styles as an uncompromisingly ‘rough’ voice. This immediately alienated many listeners but also helped to establish his own sound as being unique in the world of commercial music and a highly appropriate one for communicating harsh truths. It certainly did not stop him becoming a global star.

OTHER PROTEST SONGS

Given that Dylan ‘dashed off’ so many songs during this early period, it is perhaps not surprising that a few of these consist mainly of sloganeering and clichés. (You Been) Hiding Too Long, a song with almost no discernible melody, which was only performed once, at New York Town Hall in 1963, is an attack on false patriotism, addressed to …phony super patriotic people… who are hiding too long behind the American flag… He accuses them of betraying the ideals of the founders of the American constitution with their racism: … You say that the only good niggers are the ones that have died/ Don’t think I’ll ever stand on your side… The same is true of Playboys and Playgirls, another repetitive gospel-influenced ‘sing along’ which attacks ‘fall out shelter sellers’, ‘red baiters and race haters’ and castigates ‘the laughter in the lynch mob’.

This was performed at the Newport Folk Festival in 1963 as a duet with Pete Seeger, who encourages the audience to join in. Other songs in this vein do attempt some minimal poetic effects. Train a-Travelin’, also recorded for Broadside, is another anti-racist rant which (in its first two verses) employs some (rather well worn) metaphors: …There’s an iron train a-travelin’ that’s been a-rollin’ through the years/ With a firebox of hatred and a furnace full of fears…. Long Ago, Far Away (recorded as a Witmark demo) employs irony in a rather obvious way, cataloging a list of ills from the past that are still occurring today and concluding each verse with the refrain…Things like that don’t happen no more nowadays…do they?…

DYLAN AND SEEGER AT NEWPORT 1963

Other early compositions resembled the songs which were then being used to provide strength and support to followers of the Civil Rights movement, which was closely linked to Black American churches. Martin Luther King, the unofficial leader of the movement, delivered highly dramatic and stirring speeches that closely resembled the highly dramatic style of Southern preachers. At meetings and demonstrations, crowds would roar out communal anthems which were adaptations of gospel hymns, such as We Shall Overcome and We Shall Not Be Moved . Dylan’s Ain’t Gonna Grieve, recorded for a Witmark demo in August 1963, is an adaptation of an old spiritual with choruses which merely repeat …Ain’t a-gonna grieve no more, no more…. into which Dylan injects an anti-racist slant: … Brown and blue and white and black/ All one color on the one-way track/We got this far and ain’t a-goin’ back…. I’d Hate To Be You (On that Dreadful Day) is one of several songs Dylan contributed (under the pseudonym of ‘Blind Boy Grunt’) to sessions recorded for the agit-folk magazine Broadside. It presents a generalised message to social oppressors and corrupt politicians, warning them that they will get their comeuppance on Judgement Day. Talkin’ Devil (also recorded for Broadside) contains a verse with a particularly cutting last line which suggests that the Devil himself is a member of the Ku Klux Klan: …Well, sometimes you can’t see him so good/ When he hides his head ‘neath a snow white hood/ And rides to kill with his face well hid/ And then goes home to his wife and kids….

Dylan also began experimenting with the ballad form, using traditional tunes and adding his own narratives, much as Guthrie had done. The Walls of Red Wing, The Death of Emmett Till and The Ballad of Donald White all spell out their messages bluntly. Red Wing is set in a Young Offenders institution in which Dylan assumes the identity of a prisoner. Although the song does have an attractive melody, based on the Scottish traditional air The Road and the Miles to Dundee, there is little subtlety or irony here. The song consists almost entirely of accounts of the brutality that the inmates are subjected to. We are told that …From the dirty old mess hall/ You march to the brick wall/ Too weary to talk/ And too tired to sing…. The prisoners are bowed and beaten by sadistic guards. There are a few poetic moments, such as …The night aimed shadows/ Through the cross bar windows… and …the keys of the guards clicked the tune of the morning… But some of the rhymes such as …smilin’/wood pilin’… sound especially contrived. Joan Baez recorded a pleasant version of the song, but her ‘pure’ singing style makes the song sound, at least to the casual listener, pleasant and distracting rather than an angry protest.

Emmett Till, which was debuted on the Cynthia Gooding radio show in February 1962 and which uses a speeded up version of the melody of The House of the Rising Sun, is a venomous attack on Southern white racism. It relates the story of the 1955 murder of Emmett Till, a black teenager who was visiting his cousins in the South when he was viciously murdered by white racists for the ‘crime’ of speaking in an ‘over familiar’ way to a white shop girl. This became a cause célèbre for the Civil Rights movement after the murderers were freed without charge by an all-white jury. Later, under the protection of ‘double jeopardy’ laws, they freely admitted their crime. Several other protest songs had been written about the event. Dylan’s account is extremely graphic. He tells us that the murderers …tortured him and did some things to evil to repeat/ There were screaming sounds inside the barn, there was laughing sounds out on the street… But later he lectures his audience in a rather manic, hysterical manner: If you can’t speak out against this kind of thing, a crime that’s so unjust/ Your eyes are filled with dead men’s dirt, your mind is filled with dust/ Your arms and legs they must be in shackles and chains, and your blood it must refuse to flow/ For you let this human race fall down so God-awful low!… Although the song shows Dylan’s immaturity as a writer, his unstinting, uncensored expression of feelings here certainly engages us, predicting the venomous approach of more sophisticated songs such as Masters of War.

EMMETT TILL

Dylan took the story of The Ballad of Donald White, which is written from the point of view of White himself, from a contemporary newspaper report. It is one of the few songs in this group which uses the point of view of a narrator. Taking its melody, some of the lyrics and its narrative method from The Ballad of Peter Emberley, a nineteenth century song lamenting the accidental death of a lumberjack, it recounts the story of a man who finds it impossible to fit in with society and who only feels secure in prison. Eventually he commits a murder in order to be returned to jail, but receives a death sentence which, rather disarmingly, he seems to think he deserves. As with Emmett Till, the narrative is unfiltered and quite brutal. White’s honesty is chilling. After recounting the reasons for committing the murder he tells us …I’m glad I’ve had no parents/ To care for me and cry/ For they will never know/ The horrible death I die… He also confesses to being glad he has no friends and tells his listeners that …I guess you’ll feel much better when I’m on that hanging tree… In some ways the song recalls the confessions of sin in classic country prison songs like Hank Williams’ I Heard that Lonesome Whistle Blow and Johnny Cash’s Folsom Prison Blues; both of which are also first person narratives. But unlike the narrators of those songs, Donald White shows no remorse. By presenting his story as a first person narrative, Dylan invites us to sympathise with him. But while the song is certainly an indictment of the American mental health system, it is also clear that White is a sociopath. Thus, whereas Emmett Till dictates its morality to the audience, this song is more ambivalent. As Dylan matures as a song writer, he will alternate between songs with a clear moral message and songs which leave their conclusions more open.

Dylan’s main concerns in these songs are with social inequality and justice. His songs become increasingly dramatic, often drawing listeners into a narrative before providing a twist that turns everything around. Under the influence of radical German playwright, poet and song writer Bertolt Brecht, he also becomes skilled in the use of dramatic irony, at a level which Guthrie never attained. In the very brief Man on the Street, based on a nineteenth century song The Strange Death of John Doe, he achieves an authentically shocking effect by showing the death of a nameless old tramp in an unemotional, matter of fact way. He describes how a crowd gathers around the man, telling us that they …stopped and stared and went their way… A policeman arrives, who at first threatens to arrest the old man for vagrancy: …”Get up, old man, or I’m taking you down”… He then …jabbed him once with his bully club/ And the old man he rolled off the curb… Finally he declares …Call the wagon, this man is dead… The narrative here displays a brutal clarity reminiscent of Hemingway’s prose.

BERTOLT BRECHT

The later Only a Hobo tells the same basic story, but with a stronger tune and a rather rousing chorus: …Only a hobo, but one more is gone/ Leavin’ nobody to sing his sad song/ Leavin’ nobody to carry him home/ He was only a hobo but one more was gone… The song contains some evocative descriptions. The man’s face is …grounded in the cold sidewalk floor… We hear that …a blanket of newspaper covered his head/ As the curb was his pillow, the street was his bed… The broader social context is hinted at using deliberate understatement. In the final verse, in which Dylan appeals to our conscience, the diction of …Does it take much of a man to see his whole life go down?/ To look up at the world from a hole in the ground…. is relatively reserved and philosophical. As with Blowin’ in the Wind (discussed in a separate blog) Dylan puts questions to his audience that cannot be easily answered. The song was recorded for Broadside and later in the sessions for Freewheelin’ . It was re-recorded in 1971 with Happy Traum on second guitar and vocals for the More Greatest Hits album but never made the cut. Perhaps the definitive version is that of Rod Stewart on his album Gasoline Alley (1970), where the combination of the song’s gentle melody – enhanced by touches of mandolin – and Stewart’s rough, edgy vocal is especially effective.

The highly polemical Who Killed Davey Moore, is another ‘newspaper song’. It was never recorded by Dylan, although he played in a number of times in concert in 1963 and 1964. Davey Moore was the World Featherweight Champion boxer. In March 1963 he lost the title to the Cuban Sugar Ramos after a technical knockout. A little while later, in his dressing room, he began to complain of headaches. He died from brain damage a few days later. Dylan’s use of the framework of the nursery rhyme Who Killed Cock Robin? is part of the song’s conceit, heavily emphasising a message that could, by implication, be understood by a child. It is perhaps the first of Dylan’s ‘theatrical’ songs. It has almost no melody, but was very effective when delivered in concert as it engages the audience in the manner of a poetry recital or storytelling session. Almost the entire lyric consists of dialogue. One of its strengths is the way Dylan creates a separate voice for each character. This again indicates the influence of Brecht, who used highly literate songs in his plays, voiced by the characters, in order to advance the narrative.

DAVEY MOORE

This is another Dylan song that asks questions which it deliberately does not answer. The question …Who killed Davey Moore/ And what’s the reason for?… opens every verse and bookends the song at the end. The claims of various possible culprits are examined. All of them give the same response …It wasn’t me that made him fall/ You can’t blame me at all… First there is the referee, then the crowd, Moore’s manager, a gambler, a sports journalist and finally Sugar Ramos himself. The referee cries …Don’t put your finger at me… He admits that …I could’ve stopped it in the eighth/ An’ maybe kept him from his fate… He tell us that … the crowd would’ve booed, I’m sure/ At not gettin’ their money’s worth… Finally he shrugs …It’s too bad that he had to go/ But there was pressure on me too, you know… His assertion that the fight had to continue despite the danger to Moore is hard to sympathise with, as he seems more concerned with financial matters than the welfare of the boxer.

SUGAR RAMOS

The self-justifications made by the personified ‘angry crowd’ are even less compassionate: …We didn’t mean for him to meet his death/ We just wanted to see some sweat… The manager, who is described stereotypically as …puffing on a big cigar… declares coldly …It’s too bad for his wife and kids he’s dead/ But if he was sick he should have said… The gambler avoids responsibility by informing us that he had …put money on him to win… The boxing writer defends the sport, claiming that American Football is just as dangerous, claiming that …Fist fighting is here to stay/ It’s just the old American way… Finally Ramos himself, who Dylan describes memorably as …the man whose fists/ Laid him low in a cloud of mists… comes out with the most shocking answer of all: …Don’t say murder, don’t say kill/ It was destiny, it was God’s will… We are, of course, expected to see through these hollow declarations. The song appears, at least on a surface level, to be a condemnation of the sport; as it seems that all the speakers share the responsibility. But rather than stating that Moore’s death was the product of greed or capitalism or of the culture of violence inherent in American society, Dylan allows us to form our own conclusions. The song presents us with a moral quandary. Ramos’ final justification invites us to consider the old theological conundrum about God’s granting of free will to human beings. Was the boxer’s death pre-ordained for some unknown divine purpose? Or is the final statement an assertion that God himself, rather than any of the speakers, was responsible for the death? What, therefore, are the limitations of the doctrines of free will and predestination? And how come a supposedly loving God can allow such a tragedy to occur?

Two of Dylan’s early protest songs, John Brown and Hero Blues, focus on the evils of militarism, and in particular on the way that young men are persuaded by the women in their lives to go and fight. John Brown is a highly sombre tale. The name of the protagonist suggests a kind of ‘uber soldier’ who represents all men who are deluded by spurious promises of ‘glory’ in battle. This is another stark and polemical Brechtian drama. The melody is based on the well known folk tune 900 Miles. No historical or geographical context is supplied, so Dylan clearly intends the song as an expose of how non-combatants can be ‘cheer leaders’ for war and how naïve young men can follow their lead, often with tragic results. The song, which was first recorded for Broadside, was never considered for inclusion on a studio album. But Dylan seems to have rediscovered it later in his career as it was played live, usually with a full band backing, around 200 times between 1990 and 2012 and was included in the live album MTV Unplugged, recorded in 1994. It certainly has the kind of dramatic structure that works well with a rock arrangement.

The opening verses focus exclusively on the mother’s point of view. She smiles proudly as her son, resplendent in his uniform, sets off to war. She has clearly given no thought to the danger he will face and is far more concerned with the reflected ’glory’ that she supposes he will bring back to her. She tells him …”Do what the captain says, lots of medals you will get/ And we’ll put them on the wall when you come home”… Later she tells her neighbours …That’s my son that’s about to go/ He’s a soldier now you know… celebrating his participation in …a good old fashioned war… Dylan comments acidly that …She made well sure her neighbours understood… Then, inevitably, the narrative becomes darker. John’s letters stop arriving. After she hears that he is returning she goes to meet him from a train. But a great shock is in store for her. The description of John’s condition is uncompromisingly graphic: … His face was all shot up and his hand was all blown off/ And he wore a metal brace around his waist/ He whispered kind of slow, in a voice she did not know/ While she couldn’t even recognize his face… John is so damaged that he can hardly manage a reply. But it is clear that any idealism he may have had has gone. He tells her that while he was ..on the battleground’, you were home acting proud/ You wasn’t there standing in my shoes …

In the next two verses John gives us a harrowing description of being caught up in the madness of battle. He soon realises how futile it all is. …The thing that scared me most… he tells her bitterly …When my enemy came close/ I saw that his face looked just like mine… Perhaps we may imagine that the mother of this ‘enemy’ – who presumably John has killed – had also proudly sent her boy out to fight. John now realises that he is …just a puppet in a play… In the devastating final lines we hear that …he dropped his medals down into her hand… He has realised, far too late, that he has been manipulated. Although there is little real poetry in the song, and the outcome is arguably predictable, the song is powerful and moving, partly because of the way Dylan structures its action and dialogue. The mother’s voice dominates the early verses but it is the heart breaking riposte of the disillusioned and permanently damaged son that forms the heart of the song. This may not be a subtle message but it is delivered with great conviction.

Hero Blues, which was considered for inclusion on Freewheelin’ and The Times and was recorded as a Witmark demo, is one of the first Dylan songs that uses the form of the blues for comical effect. It consists of a complaint by a young man that his girlfriend is constantly nagging him to …go out and find somebody to fight… Dylan uses the repetition of the first lines of each verse effectively to deliver ‘surprise’ pay off lines such as this. The comically harassed narrator complains that she is his …screaming end… who wants him to …be a hero/ So she can tell all her friends… He tells us that …She reads too many books/ She got movies inside her head… Like the mother in John Brown, she wants him to fight in order to bolster her own reputation. It is certainly true that the vast majority of war movies and TV shows of the 1950s and early 1960s tended to both glorify war and avoid any realistic depiction of battlefield carnage. The main comic impact of the song comes in the third verse in which Dylan drawls …You need a different kind of man, babe/ One that can grab and hold your heart… (repeated) which is followed by the unexpected and very funny ‘pay off’ line …You need a different kind of man, babe/ You need Napoleon Bonaparte…

After this, the final verse, depicting the girl proclaiming him a hero by his graveside, seems fairly routine. Although the ‘Napoleon’ line is certainly effective, the song’s effect – which relies so much on the joke – does wear thin after a few listens. On the studio versions Dylan actually seems to treat the song fairly seriously, supplying some heartfelt bluesy vocals. But it arguably works best in a live context, as demonstrated by the performance at New York Town Hall in May 1963; where Dylan (giggling a little himself) delivers it rather in the manner of a standup comedian. The song was revived very briefly as a surprise opening number for the first two shows of the 1974 tour with The Band, now functioning as a sardonic comment on the way Dylan himself was being treated as such a ‘hero’ on his return to touring after an eight year hiatus.

DYLAN WITH JAMES BALDWIN

The melodic ballads Seven Curses and Percy’s Song, which were considered for the The Times album, both focus strongly on the issue of justice. Corrupt and unsympathetic judges are at the centre of both narratives. Seven Curses is set in some indeterminate place in a past era, possibly in the American West. It tells the story of a young woman who reluctantly agrees to spend the night with a corrupt judge in order to save her father from hanging. The judge duly takes advantage of her but hangs the father anyway. This is a very similar plot to Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure and a number of traditional ballads are based on variants of the story. Sometimes the corrupt official is a hangman rather than a judge, as in Leadbelly’s Gallows Pole, later adapted by Led Zeppelin. Dylan relates his version with great lyrical economy over a pretty finger-picked guitar figure and a melody based on Anathea, an English version of the Hungarian folk song Féher Anna (White Anna). The song has been covered a number of times, most notably by folk artists June Tabor and the Oyster Band and Joan Baez.

The song contains a number of memorable phrases. We learn that …When the judge saw Riley’s daughter/ His old eyes deepened in his head… giving us a graphic image of this lustful and evil old man. Dylan employs some examples of poetic pathetic fallacy: …The gallows shadow shook the evening/ In the night a hound dog bayed/ In the night the grounds were groanin’/ In the night the price was paid… He again skillfully places dialogue in the mouths of the characters. The lascivious judge cackles …”Gold will never free your father/ The price, my dear, is you instead!”… Old Reilly tells the girl not to accede to the judge’s demands. He says …My skin will surely crawl if he touches you at all… but sadly she ignores him. The last two verses enumerate the …seven curses on a judge so cruel… which consist of a rather odd list – one doctor, two healers, three eyes, four ears, five walls, six diggers and seven deaths. The unnamed narrator wishes him to be in such great pain that …seven deaths shall never kill him… The choice of seven does, however, seem a little random, and the ending of the song is somewhat anticlimactic. Dylan falls into the trap of delivering his own judgement on the situation, which is arguably unnecessary as the moral outlines of the story have already been clearly delineated.

Percy’s Song also features another unproductive encounter with a judge. The narrator visits the judge to plead for clemency for an unnamed friend (presumably ‘Percy’), who has been sentenced to ninety nine years in jail for accidentally crashing a car in which the passengers were killed. The judge, however, is rude and unresponsive. The song conveys deep sadness and despair but does so with admirable restraint. The beautiful flowing melody is derived from Paul Clayton’s song The Wind and the Rain; itself a variant on the traditional Scottish murder ballad The Twa Sisters. The song is also distinguished by its compelling refrain. Every second line in each of the sixteen verses runs …Turn, turn again… while every fourth line (except for in the last verse) is …turn, turn to the wind and the rain… This is reminiscent of Shakespeare’s song When That I Was a Tiny Little Boy, sung by the jester in Twelfth Night, which has a similarly structured use of the lines …With hey, ho, the wind and the rain… and …For the rain it raineth every day… Dylan’s version was not released until it was included on the collection Biograph in 1985 but the song was popularised by Fairport Convention on their album Unhalfbricking, in which lead vocalist Sandy Denny delivers a truly spellbinding performance which brings out the song’s mixture of emotions with great power and sympathy.

Much of the effectiveness of Percy’s Song lies in the way that the narrative itself is related in such a clear and unfussy way. The song begins with the portentous …Bad news, bad news, came to me where I sleep… The opening verses consist of a conversation between the narrator and an unnamed mutual acquaintance who tells him that …one of your friends is in trouble deep… The conversation is edited down to the essentials. The friend merely states …Joliet prison and ninety nine years… and later …Manslaughter in the highest of degrees…. The narrator then writes to the judge to arrange an appointment. The conversation with the judge is handled in a similarly minimal manner. The narrator is quite direct: “Can you tell me the facts”, I said without fear… …that a friend of mine would get ninety nine years”… But the hard hearted judge is not swayed by his appeal. After he states the bare facts of the case, we hear that he …spoke out of the side of his mouth… citing the testimony of a witness that …left little doubt…

The narrator‘s further appeals such as: ….Ninety-nine years, he just don’t deserve… and …What happened to him could have happened to anyone… fall on deaf ears. We are told that the judge …jerked forward and his face it did freeze… The narrator walks away in a state of sad incomprehension. The song ends with a dramatic variation on the established refrain: …And I played my guitar through the night to the day/ Turn, turn, turn again/ And the only tune my guitar could play/ Was ‘Oh, the Cruel, Rain and the Wind’… The only conclusion is that we are all subject to the ‘cruel’ vagaries of life. Injustices happen but sometimes we are powerless to reverse them. The anthropomorphised guitar, that ever-trusty source of comfort, knows this well. Percy’s Song clearly demonstrates that Dylan’s skills as a storyteller in song have become more nuanced. This time he does not deliver any curses. But by telling the story in such a relatively detached way, he makes the tragic nature of the tale more relatable.

The Ballad of Hollis Brown, which was included on The Times, makes its point with stark and devastating clarity. It relates a tale of the fate of a poor farmer in South Dakota who suffers from crop failure, which threatens him and his family with starvation. The pressure builds on Hollis until he kills his wife, his five children and then himself. The song is a highly dramatic and atmospheric morality tale which builds inexorably towards its tragic ending. It also effectively illustrates how Dylan has begun to combine his various influences. Although it is called a ‘ballad’ it uses the typically repeated lines and rhythmic guitar strumming that characterise the blues. This is partly because, in terms of its melody and approach, it is to some extent modelled on the version of the traditional murder ballad Pretty Polly, which was recorded by the blues influenced Appalachian singer and banjo player Dock Boggs. Dylan played this song several times in the folk clubs in 1961, in a version based on Boggs’ model.

As with John Brown and Seven Curses, we are not told where or when the story of Hollis Brown takes place. We could be in the Wild West of the nineteenth century or the Depression of the 1920s and 30s. Dylan may, however, have drawn the story from matters that were very much closer to home, both in terms of time and location. The song is set in South Dakota, which borders on Dylan’s home state of Minnesota. In the 1950s the state experienced an outbreak of black stem rust, devastating the wheat harvest. The fictional ‘Hollis Brown’ could well have been one of the farmers who suffered. However, the lack of historical context adds to the atmosphere of the song and makes its moral lessons more universal. Dylan played versions of Hollis Brown throughout his career, often with full band backing, with around 200 performances on the Never Ending Tour between 1988 and 2012. It was also rerecorded in the studio in 1993, with Mike Seeger on Dock Boggs-style banjo. Many cover versions exist, by artists as diverse as Barb Jungr, Iggy Pop, Nina Simone and The Neville Brothers, its use of a basic blues format making in adaptable to rock, blues and jazz arrangements.

The song begins with the ominous sounding repetitive blues riff that will be repeated throughout, reflecting the buildup of tension. The terse narrative begins …Hollis Brown, he lived on the outside of town… (repeated) …with his wife and five children and his cabin broken down… The name ‘Hollis Brown’ (which may have been chosen to facilitate the internal rhyme) is not mentioned again. We also never hear the names of his family. Dylan then switches to a rather intimate second person address. It is as if the narrator is a ‘fly on the wall’ at these events, or possibly a voice inside Hollis’ head. We hear that …You looked for work and money/ And you walked a ragged mile… which echoes the nursery rhyme There was a Crooked Man, who lives with a ‘crooked cat and a crooked mouse’ in a ‘crooked house’. Hollis himself is certainly such a ‘crooked man’, not in the sense of criminality but in the state of his mental health, as we shall learn. The next lines are especially shocking: …Your children are so hungry/ That they don’t know how to smile…

Dylan then increases the tension by switching to the present tense for the rest of the song. The throbbing blues riff mirrors Hollis’ pounding heartbeat as he descends into panic. The next few verses alternate between harrowing descriptions of how members of the family react to the situation and the distanced, unemotional narrative voice. We hear that :…Your baby’s eyes look crazy now/ They’re a-tugging at your sleeve… and later …Your baby’s a-crying louder now/ It’s a-pounding on your brain… and ..Your wife’s screams are stabbing you like the dirty driving rain… while …The rats have got your flour/ Bad blood it got your mare… and …Your grass is turning black/ There’s no water in your well… Then we get perhaps the most shocking lines of all: ….You prayed to the Lord above/ “Oh please send me a friend” … is followed by …Your empty pockets tell you that you ain’t got no friends… This is a godless universe. There will be no divine intervention to save Hollis and his family. Coyotes (animals notorious for feeding on the kills of other creatures) howl in the distance like devils. Hollis is quite literally in hell.

It is perhaps this lack of divine guidance that finally drives Hollis to his terrible act. Dylan uses repetition in successive verses to build up the pressure. In a couple of intense cinematic ‘close ups’ we are first told that …Your eyes fix on the shotgun/ That’s hanging on the wall… then …Your eyes fix on the shotgun that you’re holding in your hand… The last two verses are especially poignant …Your brain is a-bleeding/ And your legs can’t seem to stand… indicates that Hollis is experiencing a complete mental breakdown. The repetition of the word ‘seven’ now dominates the narrative. There are …seven breezes a-blowin’/ Around your cabin door… (a line which echoes Stephen Foster’s famous ballad Hard Times, another song about rural poverty, which Dylan will later cover). Then we hear that …Seven shots ring out/ Like the ocean’s pounding roar… This ‘pounding’ of the ocean is reminiscent of both the crying of the baby and Hollis’ own heartbeat. The murder itself is reported as if we are watching a long shot of the cabin in the distance as if, in this movie, the act itself is too terrible to show.

If we are in any doubt as to what has taken place, Dylan spells it out …There’s seven people dead on a South Dakota farm… clearly indicates that Hollis has killed his wife, his five children and finally himself. The concluding line puts the story in a wider context: …Somewhere in the distance/ There’s seven new people born… indicating that this awful event will soon be forgotten. Perhaps it will merit a few lines in a newspaper. Thus Hollis stands as a symbol of all the victims of poverty, war and starvation throughout history. His death has, of course, occurred in a very rich country. Thus the song can be interpreted as a protest against the lack of support for struggling farmers (and poor people in general) in the United States, with its very limited welfare system. The only ‘god’ here is Money…

Leave a Reply