THE BEATLES: Dylan, The Beatles and A Hard Day’s Night Part Two

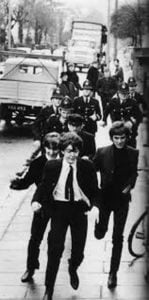

The movie A Hard Day’s Night, despite being made in monochrome on a tiny budget, is decidedly cool, witty and fast moving. It has an ‘improvised’ atmosphere that recalls the contemporary methods of French Nouvelle Vague directors like Francois Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard. As such it avoids many of the clichés of framing and narrative that characterise the ‘classical Hollywood’ style, which most British films tend to imitate. It features some use of handheld cameras and sudden ‘jump cuts’ and borrows some of the intimacy of its style from television. The sequences where the group has to escape from hysterical fans are convincingly staged and filmed, in a way that appears to resemble contemporary news footage. The director, American Dick Lester, who was approved by The Beatles mainly because, like George Martin, he had worked with John’s hero Spike Milligan, shot and cut the film to emphasise the zestful, irreverent wit of its stars. The script, by Liverpool playwright Alun Owen, is sharp, biting and subtly funny without ever attempting to raise a cheap laugh or cast The Beatles as ‘comedians’. A Hard Day’s Night is the first successful translation of the irreverent spirit of rock’n’roll roll into the cinematic idiom. Avoiding the pitfalls which had made the movies of Elvis Presley and Cliff Richard so excruciatingly corny and conventional, it is constructed as a spoof cinema-verite documentary following the group’s journey to London for, and the preparations for and execution of, a live TV appearance. All the action in the film falls within one day. Along the way the group’s main preoccupation seems to be avoiding the attentions of massed hordes of screaming fans. Rather than attempting to create characters, the group appear as themselves, which creates a cleverly ‘knowing’ effect and allows the film to make sardonic comments on the hysteria of Beatlemania, which it simultaneously parodies and celebrates. The name ‘Beatles’ is never actually used, although it is naturally assumed that the audience knows full well who they are. The use of such smart, knowing, postmodern narrative devices in a ‘pop film’ was virtually unprecedented.

Owen’s script cleverly catches the style of The Beatles’ own dry repartee, their irreverent attitude to the trappings of fame and their spontaneously witty exchanges with the press. In one rapidly cut sequence, the film features the members of the group responding to various press questions with characteristically Beatle-ish cheek. …How did you find America?… one reporter asks. John, not batting an eyelid, replies …Turn left at Greenland… The movie becomes a clever and oblique (if not too serious) commentary on fame itself – a phenomenon which The Beatles, though still near the beginning of their public careers, were already sussed enough to see many of the contradictions of. John, Paul and George are a little stiff in front of camera at times, but the film’s self-mocking style turns this into a positive strength. Most of the time they maintain deadpan expressions, as if the madness that surrounds them doesn’t really impress them at all. They are perhaps most effective when playing ‘straight men’ to Wilfred Brambell (old man Steptoe in the monumental TV comedy Steptoe And Son), who plays Paul’s curmudgeonly Irish grandfather. But it is Ringo, with his natural goofy charm, permanently put-upon expression and slightly loping, almost Chaplinesque gait, who steals the film, particularly in a poignant wordless sequence (backed by an orchestrated version of This Boy) where, having escaped from the treadmill of the group’s rehearsals, he is seen kicking cans about on some waste ground by the Thames.

The Beatles’ music, with its zestful confidence and joi de vivre, is an ideal counterpart for the fast-moving monochrome sequences that make up the film. This is perhaps best illustrated by a scene which features the group running madly around a field in a kind of manic silent-movie fashion, to no apparent purpose other than to celebrate a temporary freedom from the confines of their professional life. Partly shot from above, it is the most exhilarating and purely cinematic sequence of the movie, and the buoyant, optimistic Can’t Buy Me Love, with its dramatic and effervescent stop-start rhythms, is the perfect accompaniment. The encounter which follows this scene, in which John bumps into a young ‘intellectual’ woman who appears at first to recognise him, provides perhaps the film’s most telling moments. A laconic John denies being ‘him’ (i.e. himself), despite her examining him closely and saying …You look just like him… He claims his ‘eyes are lighter’ and finally the woman is convinced, retorting that …you don’t look like him at all… The scene, with its self-referential, almost Pinteresque dialogue, neatly parodies the pretentiousness of the intellectuals who were already beginning to lionise The Beatles, while slyly reflecting on the absurdities of fame.

Released shortly after The Beatles made their first historic appearance in the USA, the film demonstrates quite clearly that the group are highly intelligent, self-aware individuals who are not content to be presented in the exploitative way that had previously been the norm for pop stars in the cinematic medium. Even though it appeared at the height of the frenzy of Beatlemania, its showings in cinemas frequently accompanied by the screams of fans, it succeeds in satirising the processes of ‘showbiz’. Although the songs in the film are still rather limited in terms of any lyrical ‘messages’, the film holds out the promise that The Beatles may soon be able to become more forcefully articulate and artistically expressive. This was a promise that, over the next year and a half, would reach fulfilment in ways that, in early 1964, even its stars could barely begin to imagine. The film perfectly freezes the historical moment of Beatlemania, and subtly points to what will succeed it.

The Hard Day’s Night movie had arrived at exactly the right moment for The Beatles, presenting a definitive picture of them on the cusp of their phenomenal explosion of popularity. Their breakthrough in America had produced a staggering, unprecedented level of instant success which no musical artist or artists had ever achieved in such a short time. American promoters were soon rushing to Britain to book the top British ‘beat groups’ for US tours, heralding what became known as ‘The British invasion’. By the end of 1964 Beatlemania had become a worldwide phenomenon. For most of the year they were on tour, not only in ballparks and sports stadiums on a coast-to-coast US tour but also in Sweden, Holland, Denmark, Hong Kong, Australia and New Zealand. Everywhere they went they were faced with civic receptions, TV cameras and press conferences and the inevitable screaming hordes of fans. Even their arrivals back in Britain from their foreign tours were met by huge crowds. At the Liverpool premiere of A Hard Day’s Night 200,000 people lined the streets to try to get a glimpse of them. But The Beatles were growing up fast. After the most intense and hard working year of their careers, they were already becoming jaded and disillusioned with being ‘pop idols’. Standing on a hotel balcony overlooking the thousands of fans at the Hard Days Night premiere (from which they were expected to dispense suitably condescending waves at their fawning admirers) John suddenly broke ranks and began giving Hitler salutes to the crowd – this in a city which, only two decades before, Hitler’s bombers had devastated in many bombing raids. Being John, the ‘cheekiest Beatle of all’, he somehow escaped any censure for this. The national press just seemed to think he had a weird sense of humour. But John was not stupid. He could see disturbing parallels between the ‘mob hysteria’ of Beatlemania and that of the Nuremberg rallies, and although his natural response to this was merely to ‘take the piss’, already the public were being shown aspects of his darkly cynical intelligence.

At the same time, the group found themselves caught in a creative dilemma. With their series of ‘ecstatic’ singles they had perfected the ‘hit formula’ which had catapulted them to fame. But while the natural temptation of less creative souls would have been to stick with that formula, they were growing restless. From their first recordings, they had insisted on a high degree of creative freedom and control. And as their victorious tussle with George Martin over releasing only their own material on their singles had demonstrated, this insistence had been completely justified. It was one thing to be bigger than Elvis, but they certainly didn’t want to be Elvis. Their record company, EMI, were loathe to interfere with their work in the studio. After all, placing them with a non-mainstream producer like Martin, who was open to letting them have a great deal of creative freedom, certainly seemed to have worked on the commercial level. Indeed, record companies now began searching for groups who could write their own material. Through their own boldness, The Beatles had already changed the ground rules of the pop music industry. Now they were keen to explore the potential of the recording studio for creating newer sounds. This was not easy, as due to the constant pressure to keep touring they had little time to fit in recording sessions. But with the range of musical textures they had produced on the Hard Day’s Night album, they had already shown how rapidly they could progress in this area. At the same time, despite the perceived need to ‘feed’ their fans with songs they could fantasise over, the group were beginning to find the limitations of the boy-girl formula in lyric writing very constrictive. In mid-1964, John’s first book, In His Own Write – a collection of funny, often macabre little tales and vignettes accompanied by his own distinctive cartoons, which he had been working on since his schoolboy days – was published. It was acclaimed by many critics, who quite accurately identified the highly original way John played with language as being Joycean. John himself was rather bemused by this, as he had been by the attention some classical music critics had paid to his and Paul’s songs. He had never read Joyce, and his main ‘literary’ influences were Lewis Carroll and Spike Milligan. But the disparity between John’s highly creative and imaginative use of language in his book and his formulaic lyric writing was fairly glaring. Meanwhile, The Beatles’ encounter with Dylan’s work (and with marijuana) had, as we have seen, pointed them in the direction of more ‘meaningful’ self-expression. In the Hard Days Night album they had achieved a consistent, varied and constantly exuberant summation of their early style. Over the next year and a half, as they attempted to forge a new, more ‘adult’ approach, the quality of their work was to vary wildly, from the contrived to the inspired.

A version of this text appears in WHO COULD ASK FOR MORE: RECLAIMING THE BEATLES

BEATLES SITES

Leave a Reply