EXTRACTS (FULL TEXT HERE)

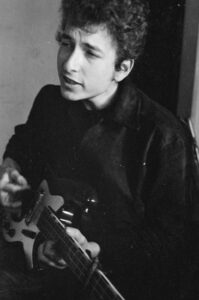

In the early 1960s, Bob Dylan was an extremely prolific writer, producing so much quality material that much of it would not fit on his albums. From a distance of several decades, it is sometimes necessary to remind ourselves that – despite the sophistication of the songs and their plethora of literary and musical references – Dylan was then still only in his early twenties. The evolution of his love songs from 1964 and 1965 reflects the longings, disappointments and emotional chaos that often characterise a period of life in which relationships start to become serious, yet may be subject to sudden and volatile change. While it is often a risky enterprise to relate particular songs to specific lovers (although fans are naturally tempted to do so) the historical facts of Dylan’s relationships with women in this part of his life are well known. In his early years in Greenwich Village he hooked up with the artist Suze Rotolo, who was just nineteen when she appeared on the iconic cover of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. She is said to have stimulated Dylan’s political awareness and encouraged him to compose the series of protest songs that made his name.

Within a year Dylan had become world famous. Fame, of course, often brings sexual temptation and like many young male stars of the period there is little doubt that he indulged in affairs and liaisons with a number of female entertainers and celebrities. Among the best known were Edie Sedgwick, a model who was a scion of Andy Warhol’s ‘Factory’ set up; Nico, the German chanteuse later to become involved with the Velvet Underground and Joan Baez, who was a similar age to Dylan but had been a prominent folk singer since the Age of eighteen. It is likely that these relationships ‘overlapped’ with each other before he secretly married model Sara Lownds in late 1965. The love songs that he composed during this period run the full gamut of emotion – from ecstatic avowals, confusion and uncertainty to extreme bitterness. They are sometimes comical, sometimes bleak and occasionally joyful. His earlier love songs had tended to be either pure expressions of devotion or nostalgia like Girl From the North Country, Tomorrow is a Long Time and Boots of Spanish Leather or philosophically detached observations on the end of relationships like Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright or One Too Many Mornings. But as he matured, the range of such songs rapidly became broader and their nature more complex.

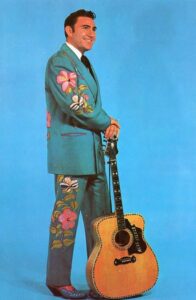

It was in country music – mainly the music of poor whites in the southern states – that the tradition of emotional realism in American song became most clearly established. Songs like Cold, Cold Heart and Your Cheatin’ Heart by Hank Williams, who Dylan (in his Poem for Joanie) called his ‘first hero’, were mostly focused on the emotional pain of heartbreak. Williams was deeply influenced by the blues but his songs conveyed this pain in a visceral way that included strongly self deprecating elements. He presented himself as vulnerable in a manner that ‘sophisticated’ singers like Frank Sinatra or Dean Martin could never convincingly convey. A song like I Fall to Pieces (written by Hank Cochran and Harlan Howard) allows Patsy Cline to ‘confess’ her own emotional instability with considerable emotional power. She Thinks I Still Care (written by Stephen Duffy and Dick Lipscomb) by George Jones depicts a lover whose attitude to his ‘ex’ is nothing less than callous. Just Can’t Live That Fast Any More (recorded by Lefty Frizell) and Webb Pierce’s There Stands the Glass catalogued the effects of alcohol and depression in destroying loving relationships.

WEBB PIERCE

Most of Dylan’s love songs of this period reflect such emotional realism, although he tends to disguise his true feelings with obfuscation and a poetic sensibility that renders the songs capable of multiple interpretations. Ballad in Plain D, from 1964’s Another Side album, however, is an exception. In this rather problematic work he describes an actual incident from his life in graphic detail and expresses his own pain and disgust at what happened in unequivocal terms. The song relates the story of Dylan’s confrontation with Carla Rotolo, Suze’s older sister, who strongly disapproved of her sibling’s romance with the scruffy young ‘beatnik’ singer. It has a strong melody, derived from the traditional Scottish air The False Bride, whose protagonist describes the pain he experiences when his lover marries another man. Dylan’s vocal performance is compelling and the recording includes an effective and poignant harmonica solo. It also has a number of evocative lines such as …shattered as a child to the shadows… …leaving all of love’s ashes behind me… and, most movingly ...I think of her often and hope whoever she’s met/ Will be fully aware of how precious she is… There is little doubt that the raw emotion Dylan expresses here is genuine. But in the song’s eight minutes and thirteen four line verses, there is scant musical variation and the tone is uniformly depressing.

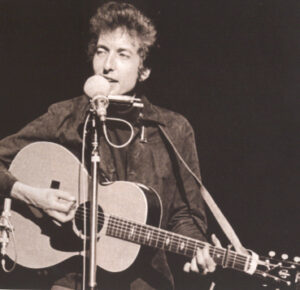

The Another Side album marked Dylan’s retreat from topical songs. By the time of its release, the landscape of American popular music had been completely changed by the unprecedented all-conquering success of The Beatles. Many of Dylan’s folk singer contemporaries regarded the British ‘beat group’ as purveyors of mindless commercialism but Dylan quite correctly recognised them as the avatars of the massive transformation of American rock music that was soon to come. His own move into playing with rock bands would be soon be another major factor in this huge cultural shift but on Another Side he was still working acoustically. Despite this, a number of the album’s songs seemed to anticipate the imminent move into rock. These songs approached the subject of love playfully, and even – in true rock and roll style – sexily. Spanish Harlem Incident is a distinctly lustful ode to a sensual ‘gypsy girl’ that the narrator encounters in a district of New York that had already been immortalised in Spanish Harlem (written by Jerry Leiber and Phil Spector and first recorded by Ben E. King in 1961), a memorable soul ballad with poetic lyrics which describe a beautiful woman as a lone ‘rose’ growing in the harsh environment of the ghetto. Dylan, however, goes straight for the jugular. His song, which has six verses and no chorus or refrain, boasts a rock-style rhythmic ‘pulse’ driven by a strongly ‘Latin’ guitar riff. It can be regarded as something of a ‘lost classic’ in Dylan’s oeuvre. There is only one known live performance, although there are a number of rock covers, including versions by The Byrds and Joan Osborne and an especially spirited take by Dion DiMucci.

From the outset the girl is described as decidedly ‘hot’: …Gypsy gal, the hands of Harlem…. Dylan begins …cannot hold you to its heat… He continues: …Your temperature’s too hot for taming/ Your flaming feet are burning up the street… He implores her to …take me/ Into the reach of your rattling drums… and declares, using barely disguised innuendo that …You got me swallowed… In another vivid phrase we hear that she has …pearly eyes so fast and slashing… and …flashing diamond teeth…. But this is not simply a tale of lust. It seems that the girl is a fortune teller, who the singer playfully demands to reveal his ‘fortune’ and his ‘lifelines’. Indeed, she appears to represent some kind of key to his future. The penultimate verse features Dylan musing …I’ve been wondering all about me, ever since I seen you there… We get the impression that he has not really formed any relationship or connection with the girl but has merely been inspired by her to create ‘sexier’ music. In the final triumphant verse, he declares …You have slayed me, you have made me… which is followed by the rather extraordinarily visceral …I got to laugh half ways off my heels… and then a final teasing (and slightly surreal) appeal to the girl: …I got to know babe, will you surround me… which is followed by the rather wonderful, if surprisingly introspective, concluding line …So I can know if I’m really real…

The song has six verses, all of which end in the tongue-in-cheek refrain … All I really wanna do/ Is baby be friends with you… The word ‘friends’ is frequently given ironic emphasis. Most of the other lines rely on repetition, mainly of ‘you’. The piling on of repetition, with the emphasis on the narrator pleading with the object of the song, has a comic effect. This is enhanced by the frequent use of internal rhyme. The song begins: …I ain’t lookin’ to compete with you/ Beat or cheat or mistreat you/ Simplify you, classify you/ Deny, defy or crucify you…. We may at first assume that this is directed at a potential lover who is sensitive to misogynist treatment. Perhaps it is a clever ruse by the narrator in ‘chatting up’ a woman. But the emphasis on the internal rhymes ‘beat/cheat’; ‘simplify/classify’ and ‘deny/defy’ sounds, in Dylan’s delivery, as if he is playing a game with the lover, presenting himself as rather charmingly assertive while still respecting her dignity and independence.

The rest of the song follows a similar pattern. The narrator declares that he does not want to ‘frighten/tighten you’, ‘shock/knock/lock you up’, or ‘drag you down/chain you down/bring you down’. Later he denies wanting to ‘analyze, categorize, finalize or advertise’ her, to ‘disgrace you, displace you, define you, confine you’, or to ‘select you, dissect you, inspect you’, ‘reject you’. In the final verses the pattern changes slightly as he states …I don’t want to meet your kin, make you spin or do you in… Finally he avows that …I ain’t lookin’ for you to feel like me, see like me or be like me… It is a memorable comic turn, with the aggressive harmonica playing between the verses emphasising the mock-pleading tone. On second listen, perhaps, fans may theorise that the song is actually directed towards them. This effect is achieved by Dylan refusing to give us any specifics of the relationship. We never find out whether this is a romantic relationship or not, although the hit version by The Byrds, which is graced by the sublime three part harmonies of Roger McGuinn, David Crosby and Gene Clark, presents the song as more straightforward declaration of love.

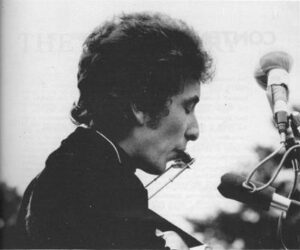

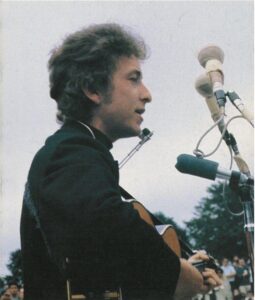

Some fans, however, suspected that Dylan was using the song to tell his listeners that he was not happy in the role of a prophet, a sage or the leader of any kind of movement. At the Newport Folk Festival on 24th July 1964 (where he performed an early version of the song) folk singer Ronnie Weaver had introduced him with the words …And here he is….Take him, you know him, he’s yours…. In Chronicles Vol. One Dylan reflects with horror on this statement, which he takes as an indication that he was now regarded as ‘public property’. Many of those in the ‘folk movement’ looked on him as a political spokesperson. This was a role that, especially in the wake of the assassination of Kennedy, he was already feeling distinctly uneasy with.

THE CAMBRIDGE BOB DYLAN SOCIETY

Leave a Reply