Please follow the link through to youtube then LIKE AND SUBSCRIBE!!!

EXTRACTS (full version here)

FRANKIE LEE – QUITE A SONG!!

The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest, from 1967’s John Wesley Harding, is perhaps Bob Dylan’s most enigmatic song. Over eleven verses and a virtually unchanging musical template, it tells a somewhat convoluted comical ‘shaggy dog’ story about the consequences of falling into too much temptation, complete with mysterious quasi-religious overtones.

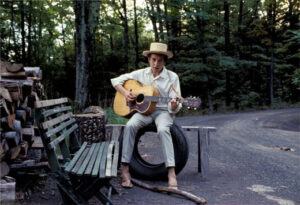

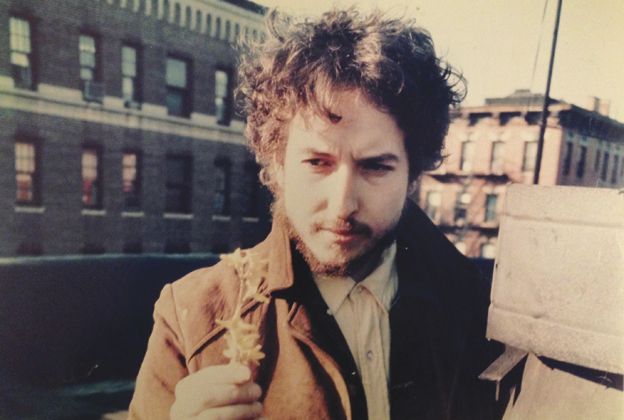

DYLAN IN WOODSTOCK 1968

Frankie Lee is a funny song…

Much has been written about the deliberate parallels that Dylan draws between the characters in the song and various religious figures. Some commentators seem to treat The Ballad as if it is a serious religious allegory, meticulously attempting to force every detail to work as part of an overall moral treatise. But such approaches unfortunately appear to ignore the obvious fact that – in terms of the lyrics and Dylan’s deadpan delivery – Frankie Lee is first and foremost a humorous discourse which, although it plays with religious and philosophical ideas, is mostly concerned with satirising moralistic notions. There is also a sense in which Dylan is playing a game with his audience, inviting them to read significance into the incongruous events that he recounts and then mocking them for doing so.

The unfolding story of Frankie Lee

The story that The Ballad recounts concerns a naïve ingénue (Frankie Lee) who borrows money from his friend, Judas Priest. After Judas departs, a ‘passing stranger’ informs him that his friend Judas is calling for him from down the road where he is ‘stranded in a house’. Frankie finds the house, which turns out to be a brothel. Losing all self control, he embarks on a mad spree for sixteen days and nights before emerging. He crashes into the waiting Judas’ arms but then (without any real explanation) suddenly dies of thirst. Given that John Wesley Harding quite deliberately presents itself as a mock-austere reaction against the excesses of rock culture and psychedelia, it is possible to read the song as an allegory of how Dylan and other rock stars plunged into overindulgence in the mid-1960s. But the song also has wider implications, despite Dylan’s tongue in cheek stance.

John Wesley Harding

This is a song with few poetic images but much snappy dialogue and witty rhyming. We begin with the jaunty….Frankie Lee and Judas Priest, they were the best of friends/ So when Frankie Lee needed money one day, Judas quickly pulled out a roll of tens… This establishes the jocular mood which will be maintained throughout the song. ‘Frankie’ is generally considered to be a slightly mocking form of ‘Frank’ or ‘Francis’. ‘Judas Priest’ is an obvious amalgam of the name of Jesus’ betrayer (name checked by Dylan in With God On Our Side) with that of a religious official. The name suggests corruption, but as Judas’ role in the song will mainly be that of a beneficiary to Frankie, the naming may well be one of the ironic jokes that pepper the song. It is then said that Judas places the money …on a footstool, above the plotted plain… The obscure phrase ‘plotted plain’ refers to an area of land that has been divided into individual plots. This may be a tongue in cheek reference to the patriotic anthem America the Beautiful, which includes the phrase ‘fruited plain’. Judas cheerfully invites Frankie to …Take your pick Frankie boy/ My loss will be your gain…

Frankie Lee: His head began to spin…

At first Frankie struggles over whether to accept the offer. We are told that …with the cold eyes of Judas on him, his head began to spin… Frankie seems particularly self conscious …Can you please not stare at me like that… he asks Judas …It’s just my foolish pride/ But sometimes a man must be alone, and this is no place to hide… It seems strange that Frankie is prevaricating now, as he asked to borrow money in the first place. The second statement is even more puzzling, suggesting that Frankie is wrestling with some deep personal problem, but this will remain unexplained. Judas winks at him and departs, leaving it up to him as to whether he will accept the money: …You better choose which of those bills you want before they all disappear!… Frankie assures him he will take the money. What follows is perhaps the song’s most bizarre moment. …Just tell me where you’ll be… He says. …Judas pointed down the road and said “Eternity” which is later qualified as …But you might call it Paradise… Frankie gives a knowing smile and says …I don’t call it anything… It seems that the pair have a mutual secret here, which they are discussing in ironically knowing terms.

Dylan covers a spectacular amount of ground in these few lines. By now it has surely become obvious that the song is in fact a parody of the Biblical story. Instead of spending forty days and nights in the desert leading the most ascetic life possible, Frankie spends sixteen days and nights indulging his carnal lusts to a ludicrous extent. In John 19:28 Jesus, in pain upon the cross, famously cries …I thirst… In Frankie’s case, the thirst extinguishes him.

Ha ha. Or is he? Has he really recast the temptations of Christ as a country and western song featuring gamblers and prostitutes? And what does ‘nothing is revealed’ actually signify? Can we link the mention of ‘nothing’ to the way he meditates on the word in several recently composed songs from The Basement Tapes such as Nothing Was Delivered and Too Much of Nothing? In these songs, ‘nothing’ becomes, ironically, a ‘thing’ in itself, signifying an absence of any underlying principle or logic behind the machinations of the world? As King Lear (a considerable influence on the Basement Tapes song Tears of Rage) states in his confusion at his daughter’s refusal to declare how much she loves him ...Nothing will come of nothing… Lear’s world is a Godless, purposeless void – the same void, perhaps, that the ‘neighbor boy’ has identified.

The final verse is delivered in the style of a Luke the Drifter-type homily, in which the narrator traditionally delivers a moral lesson to the audience. But instead of suggesting some spiritual truth, the advice given is merely simple and practical: …The moral of this song/ Is simply that one should not be where one does not belong… Then there is another reference to ‘neighbourliness’: ..And if you see your neighbour carrying something, help him with his load… Despite all the religious symbolism that is hinted at – and often parodied – in the song, the important ‘spiritual’ task here is merely to be helpful to one’s fellow human beings. But Dylan has one final admonitary twist to deliver: …and don’t go mistaking Paradise for that home across the road… The serious point here seems to be that excessive hedonism is not in itself a route to happiness, spiritual contentment or ‘salvation’.

The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest is certainly one of Bob Dylan’s most effective comic songs, even if some of its conclusions may be serious ones. In many ways it is an object lesson in Dylan’s use of ambiguity. It can be seen as a deliberate parody, not only of religious symbolism but also of those fans who exalted Dylan to the status of a prophet, frequently misinterpreting his lyrics in terms of their ‘spiritual significance’. Many of these fans, who included the crazed ‘Dylanologist’ A.J. Weberman, whose analyses of Dylan’s lyrics spilled over into disturbing paranoia, seemed to think that Dylan should be some kind of political leader of ‘The Movement’ and that his lyrics were written in some kind of secret code, within which were ‘instructions’ to his followers as to how to start ‘The Revolution’. Many years later, in Chronicles Vol. One Dylan would make clear how much he despised those who tried to place him in such a role:

…I was sick of the way my lyrics had been extrapolated, their meanings subverted into polemics and that I had been anointed the Big Bubba of Rebellion, High Priest of Protest, the Czar of Dissent, the Duke of Disobedience, Leader of the Freeloaders, Kaiser of Apostasy, Archbishop of Anarchy, the Big Cheese…

In Frankie Lee and Judas Priest Dylan strings such followers along, placing plenty of ‘clues’ in front of them and then deliberately leaving them unexplained. They will, of course, be hoping for a final revelation in the song. When it is finally delivered, by the ‘little neighbor boy’, however, it is strongly suggested that all these clues were merely meaningless. Nothing, indeed is revealed. Yet in that very ‘anti-revelation’ itself there is a kind of cry for the poet within Dylan to be released from the pressures of over expectation and over veneration which were clearly driving him to distraction. So much so, in fact, that he was now about to retreat from the public eye for seven years (during which he was only to play one major concert) and present his public with songs that could decidedly not be over interpreted.

Leave a Reply