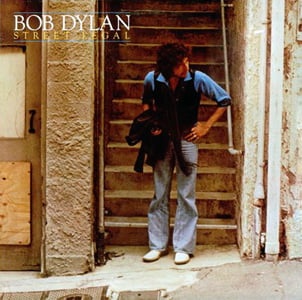

Street Legal…

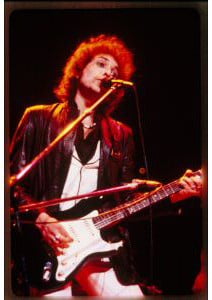

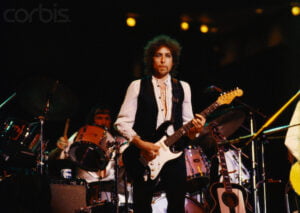

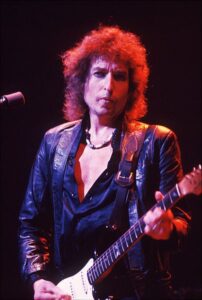

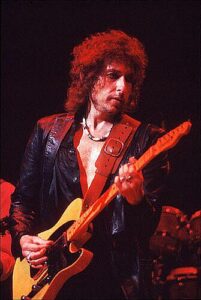

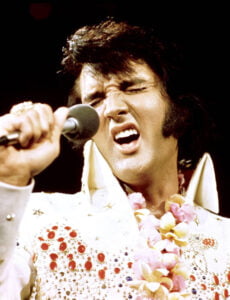

is often seen as marking a transitional point between Bob Dylan’s mid-70s triumphs with Blood on the Tracks and Desire and his upcoming and, for most of his fans, highly unsettling ‘religious period’. After the Rolling Thunder Tour ended in mid-1976, he was off the road for the whole of 1977. Much of his time was spent editing his massive film project Renaldo and Clara. That year was also notable for the death of Elvis Presley at the age of only 42, a tragedy which left Dylan devastated. In 1978 he put together a new ‘big band’ featuring keyboards, pedal steel, additional percussionists, a sax player and a trio of black female vocalists.

This ensemble may have been partly modelled on the group that backed Elvis in his endless Las Vegas residency. Jerry Scheff, who played bass on the latter part of Dylan’s tour, had actually been a member of Elvis’ band. For the first time, Dylan appeared in elaborate stage costumes. The shows would begin with the band playing an instrumental version of one of his best known songs (usually A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall) before he – as the ‘star’ – made his appearance, in true ‘showbiz’ style. It would not have been terribly surprising if, at the end of the show, an announcer told us that “Bob has left the building.”

ELVIS AND JERRY SCHEFF

The new music may also have been influenced by the live shows of Bob Marley (who used the I-Threes, his backing vocalists, prominently) and Bruce Springsteen (for whom sax player Clarence Clemons was a literally massive onstage presence).Dylan would take his new band on an extensive jaunt to Japan, Australia, Europe and the USA which lasted for most of the year. His 1978 music has a unique sound and many of his familiar songs were now presented in startlingly new arrangements, as showcased on the Live at Budokan album. The album was recorded in the spring with the same musicians during a short break from the tour. Its songs are especially concerned with the dilemmas he was facing at that particular time. Few of them were performed on subsequent tours.

Street Legal

was a rather ‘schizophrenic’ album. Four of its nine songs- Changing of the Guards, No Time To Think, Senor and Where Are You Tonight – revive the kind of arcane symbolism that Dylan had been so fond of in the mid-1960s, as well as displaying his new found interest in mysticism – especially with regard to the symbolism of the Tarot pack. The other five songs might be called ‘twisted love songs’. Love songs have always formed an important part of Dylan’s repertoire, from early nostalgic odes like Girl from The North Country to easy going romantic ditties like New Morning. Blood on the Tracks is an entire suite of songs about broken relationships. Desire ends with Sara, a desperate plea to his estranged wife in an attempt to save their doomed marriage.

After the failure of this marriage and the commercial disaster and large scale critical rejection of his cherished film project, not to mention the death of Elvis, Dylan was living through something of a personal crisis. The ‘twisted love songs’ portray him as confused, angry and – at times – even suicidal.

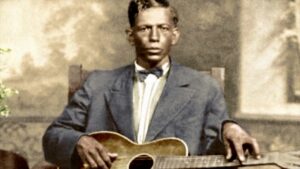

TAMPA RED AND ROBERT JOHNSON

In this context it is not surprising that Dylan turned for inspiration to one of his first loves, the Delta Blues. The great majority of Delta Blues songs were written by men who lament the fact that their women have deserted them. The women in these songs are usually blamed by the singers for what has gone wrong in their relationships. In Robert Johnson’s genuinely scary 32-20 Blues (later recorded by Dylan during the Good as I Been to You sessions in 1992) the singer even threatens to shoothis lover. Yet theblues singers rarely portray themselves in a good light. Despite the abuse that they may be directing at the woman who ‘done left me’, they often come over as weak, confused and powerless. After the instrumental introduction, Dylan began each of his 1978 shows with an old blues number. The most commonly performed were Tampa Red’s She’s Love Crazy and Love Her with a Feeling, both songs in which the male narrators express extreme awe and respect, which borders on fear, for sexually confident and independent women.

In the five ‘twisted’ songs Dylan immerses himself in a ‘blues persona’, expressing his own uncertainties through the voices of narrators who sometimesseem to be uncaring or unpleasant, especially towards the women being addressed.But as with the songs of so many Delta Blues singers, this show of ‘machismo’ only exposes the narrators’ own insecurities. In terms of musical form, however, only the vituperative New Pony can really be called a blues song. It is the first ‘pure blues’ track he had recorded since Obviously Five Believers, Pledging My Time and Leopard Skin Pillbox Hat on Blonde on Blonde. But while those songs had been reflective or comic, New Pony is dark and deliberate.It is thematically based on the great blues progenitor Charley Patton’s extraordinary Pony Blues, in which his departed girl friend is likened to a pony who the singer is determined to ‘mount’.

Like many blues songs, New Pony does not tell a chronological story. Its verses could easily be presented in a different order. They outline the narrator’s intense emotions, painting a picture of an extremely insecure narrator who is not in any way ‘reasonable’ or caring. In true Delta Blues style, he is conducting a futile attempt to assert his masculinity. He invokes the name of the Devil….I had a pony… he declaims, in his best gravelly ‘hard core blues’ voice …Her name was Lucifer…The first verse is nominally about an actual pony, who…broke her leg and needed shooting… The narrator tries to win our sympathy by trotting out the old cliché that …I swear it hurt me more than it could-a hurted her… But it is obvious from the outset that the ‘pony’ is really a woman. Although he attempts to ‘command’ her, we are left in little doubt as to who really ‘holds the reins’ in the relationship. As with many blues songs, the first line of each verse is repeated for emphasis. The backing singers ramp up the tension by chanting the insistent refrain …How much longer? How much longer?…

The next verse switches subjects. The narrator muses darkly: …Sometimes I wonder what’s going on with Miss X… Then he strings us along a little, trying to elicit a little sympathy, by stating that …She’s got such a sweet disposition… But in the following line …I never know what the poor girl’s gonna do to me next…he is back in darker territory, suggesting to us that she is teasing and tormenting him. We then switch back to references to the pony, who …knows how to foxtrot, lope and pace… a line derived from Son House’s variant on Pony Blues. More extended sexual metaphors follow: …She got great big hind legs/ Long black shaggy hair hangin’ in her face….

Meanwhile, the backing vocalists keep chanting their refrain, which now appears to imply, rather ominously, that the narrator’s patience is running out. He then addresses the girl directly, accusing her of ‘using voodoo’, telling her that …I’ve seen your feet walk by themselves… He tells her that …that God you’ve been praying to/ Gonna give you back what you’re wishin’ on someone else… Given the previous mention of ‘Lucifer’,‘that God’ is, of course, the Devil, who the paranoid narrator now fantasises will be preparing some very unpleasant payback for her exercise of her supernatural powers. Despite this, he finally gives in to lust: …Come over her pony, I wanna climb up one time/ on you/ You know you’re so nasty and so bad/ But I said I love you, yes I do… The song is a dark meditation on male sexual frustration and an expression of anger at a woman who the narrator feels is merely ‘stringing him along’. In the end, he just cannot wait any longer. Dylan uses the word ‘nasty’ in its erotic sense, implying that the woman is sexually powerful. But, as in so many blues songs, he appears to live in fear of such a woman, who seems to be a major threat to his masculine ego.

CHARLEY PATTON

The other love songs on Street Legal do not adopt a conventional blues format but could all be said to be influenced by the blues, especially in the way their narrators seem to be in thrall to the women referred to in the songs. In Baby Stop Crying, the main emotion expressed by the narrator seems to be annoyance or irritation, as he struggles to cope with a very emotional lover. The song may have been inspired by Robert Johnson’s Stop Breaking Down in which the singer expresses similar feelings. Baby Stop Crying utilises the full Street Legal band, with all its grandiose musical textures. The organ, played by Alan Pasqua, puts a smooth gloss on a sound which is slightly reminiscent at times of the texture of Like a Rolling Stone. Unlike Johnson, who sounds frustrated and angry, Dylan’s narrator is generally compassionate. Despite its blues influences, the song is constructed like a melodramatic pop anthem, with a strong, repetitive refrain. In Britain, it had some success as a minor hit single. But it differs from the typical blues song in that the narrator appears to admit his own faults and mistakes, rather than trying to hide behind incoherent machismo. The first line: …You been down to the bottom with a bad man babe… is ambiguous. Dylan does not actually spell out who the ‘bad man’ is. But the evidence from the rest of the song suggests that he himself is that ‘bad man’, who has caused her all the pain she is expressing.

The narrator tries to be reassuring …You’re back where you belong… he tells her. But this does not seem to provide any consolation. In the extraordinarily self-deprecating lines: …Go get me my pistol, babe/ Honey, I don’t know right from wrong…he appears to be admitting that he has treated her appallingly. In recognition of this, he is preparing to shoot himself. Whether he does so is not revealed but the repeated pleas for her to … stop crying… in each of the four choruses appear to reveal that there is very little that, having let her down so badly, he can say to console her. Although he tries some reassurance in the unconvincing and rather obvious final line of the choruses: …You know and I know, the sun will always shine… this seems to do nothing to stop the flood of tears.

The narrator’s admonitions continue to be vague and unconvincing. …Go down to the river babe… he tells her …And I will meet you there… He even promises to ’pay her fare’, which, perhaps not surprisingly, appears to have no effect. Then, adopting a more soothing tone, he attempts to present himself as a friend: …If you’re looking for assistance, babe, or you just want some company/ Or if you just need a friend you can talk to/ Honey, come and see about me… But the genuine compassion for someone who is suffering, which had been conveyed so believably in an early song like To Ramona, is largely absent here. The attempt at empathy in the final verse is rather misplaced …You’ve been hurt so many times… the narrator tells her …And I know what you’re thinking of/ I don’t need to be no doctor babe, to see that you’re madly in love… This is rather patronising if, as we surely suspect, it is him who she is ‘madly in love’ with. It certainly does not stop her crying. As the song ends, his attempts to console her have clearly failed. The narrator seems – like so many classic blues singers – completely wrapped up in his own problems. Perhaps, in reality, it is he who finds it impossible to ‘stop crying’.

We Better Talk This Over is another song about a failed relationship. But rather than attempting to offer the woman any hope (which, as in Baby Stop Crying, he signally fails to do) the narrator merely informs her, in a rather chaotic and emotionally numbmanner, that their relationship is finished. The song has a deceptively attractive melody and the recordinguses another fulsome arrangement, even including an extremely unusual double tracked Dylan vocal. The backing vocalists echo many of the narrator’s sentiments, repeating line after line, which adds to the claustrophobic and rather detached tone of the song. The string of rather shop soiled ‘splitting up’ clichés and mixed metaphors suggests that the narrator is trapped in a state of confusion, reduced to delivering increasingly weaker excuses for his own behaviour.

The song opens with the narrator and the woman feeling particularly depressed and suffering from a shared hangover. The narrator’s assertion that …I’m only a man, doing the best that I can… is rather pathetic. The way he rejects her in coldly detached language is particularly brutal…Why… he asks her …should we needlessly suffer?… He suggests that they should ‘go their separate ways’ …before we decay… an image which offers little consolation. When he sings: …You don’t have to be afraid of looking into my face/ We’ve done nothing to each other time will not erase…he seems to be implying that relationship has been basically meaningless and quite possibly mutually abusive. Then he descends further into maudlin self-pity. He informs us he feels ‘displaced’ and makes a brief accusation that she has been ‘double dealing’ (presumably ‘two timing’) him. He tells her, using a rather weird mixed metaphor, that …I’ve been caught in the trance of a downhill dance…addressing her rather condescendingly as ‘child’ and asking: …Why do you want to hurt me?… In a line that will soon prove to be ironic he adds: …I’m exiled, you can’t convert me…

As the song progresses the narrator sinks into hopelessness. Lines like …It’ll be great to cross paths in a day and a half/ Look at each other and laugh… and…I don’t think it’s liable to happen/ Like the sound of one hand clapping… are strangely incoherent. The reference to the Zen phrase ‘the sound of one hand clapping’ is particularly contrived. Later mixed metaphors become even more convoluted:…Why should we keep watching each other through a telescope/ Eventually we’ll hang ourselves in all this tangled rope…while ‘brush off’ lines: …Don’t think of me and fantasise about what we never had/ Be grateful for what we’ve shared together and be glad…are shallow and patronising. Finally he declares, in another awkward collocation…I wish I was a magician/ I would wave a wand and tie back the bond/ That we’ve both gone beyond…

A one off live revival, performed in Anaheim in 2000, features a harsher and thus perhaps more appropriate vocal. The lack of humanity that the completely self-absorbed narrator displays here is almost breathtaking. As with Baby Stop Crying, it may be that Dylan is turning inwards again, conveying a picture of a soul in torment. The song can also be taken as a somewhat desperate message to his audience and perhaps even his whole generation, almost as if he is ‘signing off’in despair from his role as a public poet. All that’s left, it seems, is a hangover.

True Love Tends to Forget is something of a conundrum. It is a more compassionate song but it still conveys a considerable degree of negativity and despair. Despite this, the song comes closer to a melodramatic pop style than any of his previous compositions. In some ways it even resembles the work of the perennially unfashionable but always popular Neil Diamond. The backing singers are used more sparingly here, mainly as support on the many repeated refrains at the end of every verse. It seems that the narrator is desperately trying to reassure himself that ‘true love’ is really a factor in this relationship. In reality he appears to be participating in another basically meaningless tryst, so much so that he is barely ‘present’ in terms of emotional engagement.

The song begins…I’m getting weary looking into my baby’s eyes… a clear reversal of a typical romantic cliché. …When she’s near me… he confesses …she’s so hard to recognise… Perhaps the narrator has had so many casual and meaningless affairs recently that his partners seem to him to be interchangeable. But something about her seems to have triggered some elements of his conscience. He declares that …I finally realise there’s no time for regret… Perhaps he has decided to be honest with this lover about how he really feels. But unfortunately it seems, from what follows, that he does not feel very much. Perhaps, however, he really does not know how he actually feels.

From the second verse onwards he switches to a direct address. In this case, however, he does not appear to be giving his lover her ‘marching orders’. He at least puts up the pretence of making a romantic appeal, beginning with the rather tender, if doubtful …Hold me, baby be near/ You told me you’d be sincere… But then he spirals off in a similar path to We Better Talk This Over, resorting to using a series of rather strangely disconnected metaphorical phrases which present a very negative view of the relationship. He tells her that …Every day of the year’s like playing Russian Roulette…and later that …This weekend in hell is making me sweat… These, of course, can hardly be called romantic entreaties. Lines like ….You’re a tear jerker baby but I’m under your spell/ You’re a hard worker baby but I know you well… are equivocal at best. Eventually he criticises her for …keeping me knockin’ about/ From Mexico to Tibet… which seems rather like a random phrase thrown in to make a rhyme. By the end of the song, the hints of romanticism have all but disappeared.

Perhaps the most beguiling part of the song is the repeated bridge section, in which the narrator appears to be imagining himself in a variety of strange geographical locations and odd situations. First of all we hear that …I was lying down in the reeds without any oxygen… There is no explanation of where these ‘reeds’ are or why lying down in them means he cannot breathe. This may be some kind of metaphor for how he feels ‘choked’ by the relationship. The next line …I saw you in the wilderness among the men… gives us a ‘jump cut’ into another mysterious scenario entirely …I saw you drift into infinity and come back again… is a more evocative line, suggesting that his ‘vision’ of her is alternately fading away and getting brighter. He promises her that …All you have to do is wait and I’ll tell you when… But no such order or revelation occurs. True Love is another ‘twisted love song’ which illustrates both its narrator’s confusion and his disillusionment with love itself. This is another song in which, despite the smoothness of the ‘big band sound’ which dominates Street Legal, the depths of personal despair that Dylan seems to be experiencing are revealed.

In the passionate and morally ambiguous Is Your Love in Vain, however, Dylan articulates such feelings in a powerful and more focused way. The rich musical texture, which builds towards a series of understated climaxes, strongly supports this. He expresses complex emotions in a way that few popular songs have ever done. The narrator does not present himself as a particularly enlightened or wise individual but the emotions he expresses come over as extremely authentic. Here Dylan carries out a forensic examination of the relationship between love and art. As many critics had pointed out over the years, his most memorable and resonant work had generally been produced when he himself was in the throes of personal chaos or bitter confrontation, as songs from Like a Rolling Stone to Positively 4th Street to Wedding Song and Idiot Wind bore witness. His ‘happier’ periods as a ‘family man’ living away from the limelight produced songs like Lay Lady Lay, If Not For You, Knockin’ on Heaven’s door or Watching the River Flow which certainly had their merits but could never match the songs written in ‘unhappy’ periods in terms of poetic imagination and revolutionary advances in the art of song. For Dylan, being in a happy settled relationship has proved to be virtually impossible to reconcile with reaching his artistic potential. Is Your Love in Vain confronts this dilemma head on, in a way that few songwriters have ever attempted.

The language of the song is clear and forthright and is expressed in a stately and dignified tone.Whereas in some of the other Street Legal songs Dylan attempts to communicate through complicated metaphors, here he appears to be speaking directly from the heart. The opening couplet …Do you love me, or are you just extending good will/ Do you need me half as bad as you say, or are you just feeling guilt?… establishes an emotional distance from his lover as he questions whether her devotion is genuine. He sounds very wary of making a commitment, delivering the wonderfully compressed …I’ve been burned before and I know the score/ So you won’t hear me complain… He then asks a very direct question…Will I be able to count on you, or is your love in vain?…Such a clear expression of reticence is very unusual for a ‘love song’. The phrase ‘love in vain’ is the title of a brilliantly anguished blues classic by Robert Johnson, who laments the departure of his woman by reflecting back philosophically on his own state of mind. Dylan’s narrator maintains here that he will not be reduced to such desperate emotional dependence. But perhaps this is all bluster. The ambiguity of the address leaves room for interpreters of the song to tilt it in different directions. In Barb Jungr’s beautifully paced ‘stripped down’ version, which is performed in a tone of barely suppressed emotion over a solo piano, we sense that the narrator is merely pretending to be so detached. It is even possible to interpret the first verse as an address by the lover to the main narrator, with the rest of the verses being his response.

In the second verse, Dylan confronts the ‘art vs. love’ dilemma directly …Are you so fast that you cannot see that I must have solitude… he begins …When I am in the darkness, why do you intrude?… Here he seems to be expressing the artist’s age old dilemma in tearfully heart breaking terms. He seems to be telling the lover that as a poet he needs to explore an inner ‘darkness’, confronting feelings that cannot be shared with othersand which thus must be kept secret. This is clearly a heavy burden to carry. But in a way, the line is also a declaration of independence. The narrator appears to be laying claim to this ‘darkness’ as being a psychological condition that only he can understand. This might appear at first to be a rather egotistical claim. But the line does appear to be a recognition by Dylan of his own particular genius. Never normally one to ‘blow his own trumpet’, he seems, however to have come to the realisation here that his career as a writer and his love life must remain separate …Do you know my world, do you know my kind… he asks, with a hint of impatience: …Or must I explain?… Nobody else, it seems, can see what Dylan sees in the ‘darkness’of his inner soul, in which the origins of his extraordinary poetic inspiration lie. He tells his potential lover that this ‘inner space’ must remain sacrosanct. This is spelled out in no uncertain terms: …Will you let me be myself, or is your love in vain….

The song has one particularly resonant bridge section, which seems to sum up Dylan’s own attitude to the vagaries of fame in delightfully ambiguous terms: …I’ve been to the mountain and I’ve been in the wind…he sings, recalling both A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall, where he states that he will …reflect from the mountain… as a he looks down on a devastated world and Blowin’ in the Wind, which like Is Your Love in Vain consists mainly of a series of rhetorical questions. He then contextualises this clearly in terms of his own love life: …I’ve been in and out of happiness… which is followed by the deft and world weary humour – punctuated by ironic rhyming – of …I have dined with kings, I’ve been offered wings/ But I’ve never been too impressed… Dylan now seems to have reached a crucial point of self-awareness. Here he expands the scope of the song, so that he seems to be talking about the problems of maintaining the kind of poetic inspiration he can reach ‘in the darkness’ while having to cope with the illusions of fameand celebrity which he himself has had to cope with from a very young age. The song is thus as much about his relationship with his adoring fans, who may claim to ‘love’ him, as with any woman. It is also a wake up call, through which he warns himself not to get carried away with all the adulation he has received.

Now that Dylan has established the parametersof how much he can give, either to alover or his audience, he can relax. In another key moment in the song, whichcreates a remarkable emotional reverberation, he declares, with a tiny self-deprecating laugh …All right, I will take a chance/ I will fall in love with you/ If I’m a fool you can have the night/ You can have the morning too… But having told her that he will ‘submit’ to her demands, he then turns the focus back on her, asking if she is really prepared to play a role in the relationship which will not involve her ‘intruding’ on his creative ‘darkness’. The song climaxes with the ‘controversial’ lines: …Can you cook and sew, make flowers grow/ Do you understand my pain?…These lines have been taken out of context by some commentators in an attempt to prove that Dylan is a ‘sexist’, with the implication, perhaps, that he is suggesting that ‘cooking and sewing’ is all women are good for. Such an interpretation fails to take into account that this song, like most of Dylan’s work, is expressed through the persona of a narrator. Also, the song can be sung by a woman to a man (as in Jungr’s version) and can make as much emotional sense. These lines, which are partly tongue-in-cheek, certainly do ask his potential lovers to find (possibly trivial) ways of amusing themselves. The implication appears to be that they need to respect that his forays ‘into the darkness’ are highly personal inner explorations. The second line puts great emphasis on the sacrifices and suffering that an artist must endure in order to function in such a space.

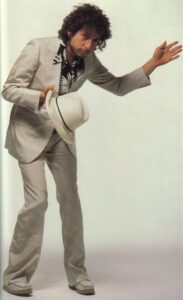

ELVIS

The final line: …Are you willing to risk it all/ Or is your love in vain?… leaves the question of whether this potential relationship will actually be successful to the listener to decide.At the same time, the entire song can beseen as an internal dialogue. Despite ‘dining with kings and being offered wings’, instances of which will inevitably occur in the future as he gathers more adulation and accolades, the singer needs to keep his feet firmly on the ground and not be distracted by all this attention. The fate of Elvis has provided him with a dire warning about the consequences of fame – of accepting so much ‘love’ that one drowns in it. Like Elvis, he has been ‘offered wings’ but unlike ‘the King’ he has the good sense not to strap them on. Otherwise, like Icarus, he might find himself flying far too close to the sun.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XVJvliFNhtI

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vUkqI9ROfkQ&t=388s

Leave a Reply