BOB DYLAN: TO RAMONA – THE FINISHING END

To Ramona stands alone in Bob Dylan’s catalogue. Although it is clearly addressed to a girl, it is neither a devotional love song like Tomorrow Is a Long Time nor a rueful farewell to a relationship like One Too Many Mornings or Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right. Although it displays a rather restrained but unmistakeable eroticism, it is a song not of longing but of condolence. The narrator is comforting a girl who has clearly been suffering. But he is steadfast in that he will not take advantage of her. Ramona is a fragile figure. But although the narrator is offering solace, he knows that he is powerless to really help her. Dylan is of course known for vituperative ‘put down’ songs like Positively Fourth Street or Like a Rolling Stone. But To Ramona is perhaps his most movingly compassionate song. Here he conveys emotions that are very obviously passionately heartfelt, while exploring the complex nature of human relationships in a distanced, philosophical way.

The song’s musical construction is a crucial part of the way Dylan frames the address to the girl. The influence of corrido, a popular Mexican form of the romantic ballad, with its distinctive rising and falling cadences, is central to this. The song has some resemblances to the mournful country standard The Last Letter, a 1937 hit for Rex Griffin whose singer appears to be so low that he is threatening suicide now that his loved one has left him. But To Ramona switches this around. Here it is the girl whom Dylan is consoling who is in a desperate state. The insistent use of internal rhyme and alliteration adds a sheen of ironic reflectiveness to all this. The song is full of dualisms – life and death, breath and death, a vacuum and a scheme, reality and fantasy, North and South, nothing to win, nothing to lose… The delicacy with which the narrator handles the situation is reflected in the graceful waltz time that dominates the song. The two characters are ‘dancing’ around each other, but always at a formal distance.

The first two lines provide, in only eight words, a clear flavour of the poetic qualities of the song: …Ramona, come closer… the narrator begins, already using internal rhyme and two soft alliterative phrases to entice us …shut softly your watery eyes… Already we can imagine the scene. The girl is crying and he is comforting her. In …the pangs of your sadness will pass and your senses will rise… he is giving her some inspirational advice. The word ‘pangs’ is normally used to apply to anxiety. The way Dylan connects it to ‘sadness’, and then contrasts the ‘p’ and ‘s’ sounds, so reiterating the alliteration in a more complex way, makes us imagine the pain she is feeling in a few ‘sharp’ words. The reference to the ‘death like’ ‘flowers of the city’ and another dualistic rhyme …There’s no use in tryin’/ To deal with the dyin’… suggests that this may well be some kind of grief. Grief can, however, take many forms. Perhaps the girl is actually suicidal and is grieving for herself.

We then get a little more context. The narrator confesses that he’d …still like to kiss… her …cracked country lips… He delivers the memorable, and even more alliterative tribute …Your magnetic movements still capture the minutes I’m in… It seems that she understands him, in a way that thrills him but also possibly scares him. It soon becomes clear that she is under certain influences that have a strong pull on her, which the narrator scornfully refers to as …a world that just don’t exist… He implies that she has been ‘brain washed’ by those who have attempted to force her to believe in a false reality. The statement that she is …torn between staying and returning back to the South… suggests that this ‘country girl’ cannot flourish as a ‘flower of the city’ and that she is being pressurised to conform to traditional beliefs. The narrator quite explicitly tries to get her to see that she has been hoodwinked. He tells her that …I can see that your head has been twisted and fed/ With worthless foam from the mouth… and that she has …been fooled into thinking that the finishing end is at hand… The expression ‘finishing end’ – actually a term from metal working – is another one of Dylan’s characteristic uses of double emphasis, like the description of the girl in I Don’t Believe You whose mouth is described as being both ‘watery’ and ‘wet’. The use of the term here strongly suggests that the girl has indeed contemplated suicide. Or perhaps fundamentalist zealots from ‘The South’ have convinced her that ‘the end of the world is nigh’. The narrator’s response to this is highly sympathetic and inspirational. …There’s no-one to beat you, no one to defeat you… he declares …’Cept the thoughts of yourself feeling bad… The rather odd word order of the second line adds to the evocation of her confusion.

The last two verses consist of an impassioned appeal to the girl which positions the song as a kind of philosophical statement about fighting conformity of thought. The powerful opening lines of the fourth verse: …I’ve heard you say many times you are better than no-one/ And no-one is better than you…. presents, through another reversed duality, an insight into the fact that the girl has gained tremendous self respect in looking outside her traditional beliefs. He tries extremely hard to galvanise her into throwing off the apparent sense of guilt she is now carrying: …If you really believe that you know you having nothing to win and nothing to lose… He seems to be reinforcing the message that the real duality is in her mind, and that she should not allow those who consider themselves ‘better than her’ to drag her down. He identifies the source of her mental distress not as coming from her but from …fixtures and forces and friends… who …hype you and type you, making you feel/ That you gotta be exactly like them… Thus we get the impression that if only she could throw off these societal demands, she could be free.

If only it was that easy… Finally the narrator has to admit that his words of consolation and inspiration may be being wasted. He realises that the longer he tries to convince her, the more his words will become meaningless. To Ramona thus questions the limitations of language, and of poetic language in particular. He confesses that: …Deep in my heart I know there is no help I can bring… Thus he gives up trying to persuade her to accept that her problems can all be solved ‘inside her own head. In the wonderfully compressed denouement of the song he reflects with a Zen calm and a ‘whatever will be will be’ attitude ...Everything passes, everything changes/ Just do what you think you should do… he tells her. Then in a final dramatic demonstration of duality, tells her …And someday baby, who knows, baby/ I’ll come and be crying to you…

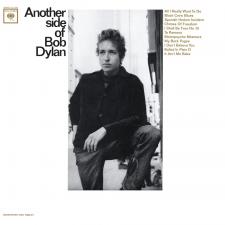

So we come to the obvious question. Who is Ramona? Apart from her ‘cracked country lips’, we are never told what she looks like, where she actually comes from, or what those beliefs that appear to be dragging her down actually are. The song appears on the surface to consist of the narrator telling her that she is just not suitable for him. In that sense it might be seen as another song of rejection like Don’t Think Twice. Given the time of its composition, some commentators have interpreted the song as being directed to one of his romantic interests at the time such as Joan Baez or Mavis Staples. Baez even claims in her autobiography And a Voice to Sing With that Dylan sometimes even addressed her as ‘Ramona’. With her ‘sultry’ Latino looks she certainly seems to fit the bill, or at least the name. But to narrow down the song to being a complaint about a specific lover is to narrow down its focus and to underestimate the way Dylan was now using the medium of the ‘love song’ to address wider concerns. To Ramona appears on Another Side of Bob Dylan (1964), his last album before ‘going electric’ but the first to break with his role as a ‘protest singer’. Several of the ‘love songs’ on the album can be interpreted as messages to his audience. The exaggeratedly comic opening track All I Really Want to Do and the scathing closer It Ain’t Me Babe are both messages to lovers through which Dylan also appears to be talking to his audience. For the first time, he steadfastly rejects the role of ‘prophet’ or ‘saviour’ which fans of his protest songs were trying to push him towards. …It ain’t me you’re looking for… he tells them. He doesn’t want to ‘track or trace’, ‘define or confine’ them. He just wants to be friends.

To Ramona is placed midway between these two apparently coded messages. It is more ambiguous than them and more clearly focused on a specific relationship. But here Dylan’s address to the girl can also be seen as a message to himself. He is just about to launch huge changes to his career and in some ways the song can be seen as him attempting to give himself the courage to do so. ‘Ramona’ may represent the spirit of doubt, or of lassitude, that keeps true artists moving on. One certainly gets the strong impression that the narrator is quite vehement that he cannot give himself to the girl. In the end, like the narrator of Desolation Row, he opts ‘not to think too much’ and let whatever happens happen. Thus he may have accepted that ‘Ramona’ is not a quality that one should reject but a facet of oneself one should accept. It may also suggest that Dylan is confronting his ‘female’ qualities and seeking for ways to integrate them into his personality. In many ways the ambiguity and complexity of the song presages Dylan’s work on Blonde on Blonde, a series of songs which are addressed to ‘translucent’ or symbolic female figures, all of whom can be seen as aspects of the main narrator’s personality. The dynamics of To Ramona also look forward to the shifting narrative ambiguities of his post-Time Out of Mind work.

What distinguishes the song most of all is the beautifully lucid way it expresses emotions that are rarely depicted in popular songs, such as compassion, selflessness and pity. Dylan skilfully manipulates a range of poetic techniques to draw us into the emotional core of the song. The most powerful message the song conveys is the importance of individual autonomy – of finding one’s own way despite the pressures of society and its ideologies. Yet the tragedy of the song is that the narrator knows he cannot make the girl follow his advice. He is, after all, another voice of persuasion. She must go her own way, right or wrong. To Ramona thus depicts an internal struggle that we all feel to some extent – whether to conform to society or to go our own way and risk being cut off from others. This was, of course, an especially pertinent theme in the mid-1960s as so many young people were opting to ‘drop out’ of conventional society. Dylan knows that he himself needs to discover the strength to change his entire musical personality. But the way the narrator abandons his attempt at persuasion and allows fate to take shape requires real courage. We can feel that courage, along with deep feelings of compassion and sympathy in this song. There may be times when we may all feel exactly like Ramona – down and depressed, full of despair, even suicidal. At those times, Dylan is telling us, you have to accept your situation and realise that you have …nothing to win and nothing to lose…

DYLAN LINKS

DAILY DYLAN NEWS at the wonderful EXPECTING RAIN

THE BOB DYLAN PROJECT- COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

THE CAMBRIDGE BOB DYLAN SOCIETY

Leave a Reply