EXTRACTS (Full text HERE)

BROWNSVILLE GIRL

Brownsville Girl is an extraordinarily experimental song which is a unique amalgam of lyrical, cinematic and theatrical elements. Its use of fractured internal and external narratives and time frames links it to earlier songs like Tangled Up in Blue and Visions of Johanna. But it uses language in a very different way. The lyrics were co-written with leading American playwright and actor Sam Shepard. Part sung and part spoken, it mixes startling poetic imagery with prosaic and clichéd expressions in what is often a highly disarming manner. The music follows a basic pattern of rhythmic repetition, allowing Dylan to enunciate a number of extended lines, as many blues singers are wont to do. These lines also do much to give the song the flavour of the heightened ‘everyday speech’ favoured by the most influential modern dramatists such as Harold Pinter and Arthur Miller. The song is held together by a distinctly ‘sing-along’ chorus which appears at unusually spaced out intervals. The first chorus appears after six verses, the second and third after four verses and the final one after another three verses. This distorts the ‘time continuum’ of the song, making it appear shorter than its twelve minute length.

DYLAN, SHEPARD AND BROWNSVILLE GIRL

Dylan and Shepard had collaborated before. In 1975 Shepard wrote a script for Dylan’s film Renaldo and Clara and accompanied the musicians on much of the first leg of the Rolling Thunder tour. As he reveals in the Rolling Thunder Logbook, his idiosyncratic account of the tour, much of his text was not used in the movie as Dylan tended to favour more improvised scenes. But the disassociated sensibility of the film, which focuses particularly on issues of identity, has a number of links to Brownsville Girl, especially in its mixture of Shepard’s typically offhand, laconic dialogue and Dylanesque symbolism. Like Renaldo, Brownsville Girl is a kind of ‘road movie’ in which the characters can be said to be constantly travelling in order to ‘discover themselves’. In that sense both works have a debt to Kerouac’s On the Road. Shepard had a long and prolific career, producing over fifty plays and appearing in around seventy films. His plays often feature ‘outsider’ characters, include surreal and poetic moments and elements of black comedy, which he uses to make what are often barbed comments about American society. Perhaps his most famous work is True West (1982), an intermittently funny and tragic satire on the Hollywood screenwriting system and the quintessentially American values it represents. In 1987 Shepard wrote True Dylan, a one act play consisting of a dramatised ‘interview’ with Dylan. He was also involved as a screenwriter for Zabriskie Point (1970), Oh! Calcutta (1972) and Paris, Texas (1984) and went on to direct a number of films.

The film is one of a series of ‘revisionist Westerns’ made in the 1950s (an era in which the Western was the dominant Hollywood genre) which introduce variations on the conventions established in hundreds of previous cowboy movies., often in order to comment on contemporary issues. Perhaps the most well known is High Noon (1954), often seen as an allegory on the McCarthyite anti-communist witch hunts of the 1950s. Most ‘traditional’ Westerns end up in a shootout which is usually won by the hero. But in this case the boy merely shoots Ringo in the back. There are moments in the song when Dylan’s own voice appears to break through, where he reflects on his own position as an ageing rock star being challenged by ‘young guns’. Like Peck’s character, he seems disillusioned and exhausted by the pressures of fame. This is especially poignant given the generally negative reviews of his work in the late 1980s; an era in which he himself – as he later recalled in his memoir Chronicles Vol. 1 – thought of himself as being ‘washed up’ and claimed to have seriously considered retiring.

In the next verse the mixture of ‘close ups’ and emotional reflection shows Dylan and Shepard working together with great effectiveness. The evocative image conjured up by …I can still see the day that you came to me on the Painted Desert/ In your busted down Ford and your platform heels… is highly cinematic in its attention to specific detail. The Painted Desert is an area of northern Texas, while the description of the ‘busted down’ car is contrasted with the depiction of the woman as wearing the kind of impractical footwear that was especially popular in the 1970s. This immediately establishes her character as being both adventurous and self consciously showy. The following (equally economical) lines convey the narrator’s nostalgic longing with great emotional force: …I could never figure out why you chose that particular place to meet/ Ah, but you were right. It was perfect as I got in behind the wheel…

We then hear an account of their ‘freewheeling’ journey through Texas. They drive all night to San Antone and then sleep …near the Alamo… which is of course one of the most iconic sites in the USA. The narrator’s memory of their love making is very effectively and economically expressed in the simple line …Your skin was so tender and soft… a highly visceral description. Suddenly they are …way down in Mexico… where she goes out to find a doctor but never returns. This action, which has some similarity to the end of On the Road when Dean Moriarty deserts Sal Paradise with no explanation, suggests that she may have had some unknown motive for her disappearance. This, however, remains a mystery, as does the narrator’s assertion that …I would have gone after you but I didn’t feel like getting my head blown off… This is the first suggestion of his involvement with some kind of criminal activity.

The final verse of the first section is particularly revealing, beginning with another highly cinematic description as the narrator now takes us into what we seems to be the ‘present moment’ of the story: …Well, we’re drivin’ this car and the sun is coming up over the Rockies… We may at first assume that this is a continuation of the journey described in the last few verses. But the geographical reference tells us that in fact he is now on a different road trip, which is considerably further West. Just as the Western genre came to encapsulate and represent the mores of American culture, so the notion of ‘The West’ itself became symbolic of the uniqueness of that culture, in which the inhabitants were always pushing the national consciousness into ‘new frontiers’. Many of Shepard’s plays are set in the modern West and cast a dubious light on such notions.

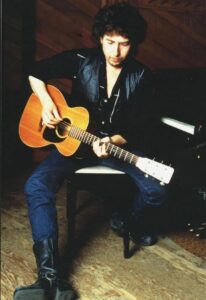

SAM SHEPARD

Dylan then delivers several lines in which he breaks away from the rhythm of the song, expressing his feelings in a kind of stream of consciousness. Her reveals that he is now with a different woman. In the next line … Now I know she ain’t you but she’s here and she’s got that dark rhythm in her soul… it is suggested that he is with this woman because of her resemblance to the Brownsville Girl, thus suggesting that in his current life he is ‘living a lie’. Despite being with a different lover, he continues to address The Girl in his mind: …But I’m too over the edge and I ain’t in the mood anymore to remember the times when I was your only man… This long line is followed by the terse …And she don’t want to remind me. She knows this car would go out of control… suggesting that this other woman is quite aware of his obsession with his previous lover.

In the third section there are more hints that the narrator is on the run from the police. Again we are provided with selected fragments of his memory so it is impossible to tell what has really happened. We are first told, rather bizarrely, that …They were looking for someone with a pompadour… a hairstyle that was popular in the 1950s and was worn by Elvis Presley, Tony Curtis and – most spectacularly – the flamboyant Little Richard, Dylan’s early hero. The narrator recalls being shot at and delivers the wonderfully funny deadpan line …I didn’t know whether to duck or run… so I ran… We then learn that The Girl made a court appearance, saving him by testifying that he was with her at the time of the crime. We never find out, however, what this crime actually was.

As the song nears its climax, more and more lines seem to suggest that the voice of Dylan himself is now coming through, in his typically enigmatic way. We learn that The Girl had seen his photo in the local paper with the caption …A man with no alibi… which recalls previous ‘offhand’ Dylan characterisations such as Alias in Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973). The long line ….Now I’ve always been the kind of person that doesn’t like to trespass, but sometimes you just find yourself over the line… sounds like a confession of regret from someone who has the habit of pushing his relationships – or other involvements – too far. In another highly ambiguous and funny statement he declares …If there’s an original thought out there I could use it right now… At the time many listeners took this to refer to the lack of inspiration that Dylan appeared to be suffering from in the late 1980s. The line is ironic, though, as the last thing that Brownsville Girl is short of is a lack of originality. Having delivered this ‘confession’, we are presented with a memory of him ‘standing in line’ to see a Gregory Peck movie, which may or may not be the film previously referred to. Dylan tells us that …he’ll see him in anything… Thus the narrator and Dylan himself appear to be merging personalities, while the memories being related become more and more suspect. It may be argued that the unreliability of memory is one of the main themes of the song.

By the time we reach the final three verse section, the memories of the relationship with The Girl are dissolving. All we are left with is a series of enigmas. In a conversational tone, the narrator begins to philosophise about fate: …You know, it’s funny how things never turn out the way you had ‘em planned… which is a kind of inverted version of the famous line from It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue: …Take what you have gathered from coincidence… It seems that Dylan is looking back to his younger days, with the sad reflection that the spontaneity that fuelled his earlier work has now dissolved, along with many of his actual memories. Years later, in Chronicles Vol. 1, Dylan would write an entire ‘autobiography’ in which the veracity of memory was constantly being challenged.

The ‘Brownsville Girl’ herself remains a truly inscrutable figure. We are never told what she looks like, where she comes from or what her motivations are. Like the girl on the Red River Shore or the subject of Just Like a Woman, she appears to be more like a collection of memories than a real person. Perhaps she is merely as aspect of Dylan’s own imagination. Dylan appears to be using his narrator to look back from middle age on the wild excesses of youth and his own dedication to being always ‘on the (metaphorical) road’ in terms of his constant changes of style and ‘freewheeling’ attitude to art and life. The song is a kind of meditation of the persistence of memory itself. Despite all the disappointments and wrong turnings in life it recounts, it ends rather triumphantly, with the lovers being back on the highway, not knowing where that road will leave them.

Brownsville Girl takes us on a very unusual rollercoaster ride. In doing so it uses the enigmatic language that is characteristic of the modern hyper-realistic dramas of playwrights like Shepard, mixed with cinematic flashbacks and flash forwards to tell a story whose ‘reality’ is psychological rather than historical. All this is held together by apparently highly sentimental and romantic choruses, which provide a kind of blessed relief from the contorted narrative. As in a number of other Dylan songs, the framework of a love song is presented ironically, with Dylan using this conventional structure to reflect on psychological realities. The song is crammed with ironic humour and nostalgia. But it is also infused with a particular determination to carry on exploring the elements of the creative imagination. It is a song, like so many others in Dylan’s catalogue, about the struggle to retain or regain artistic inspiration in the face of a world with little understanding of the real rigours of the process of artistic creation.

Leave a Reply