North Country Blues could be called Bob Dylan’s most obscure protest song. Tucked away at the end of the generally bleak Times They Are a-Changin’ album, it has never, like the terrifying ‘murder ballad’ The Ballad of Hollis Brown, been electrified. Unlike Dylan’s ‘alternative history lesson’ With God on our Side it has not been subjected to endless earnest cover versions. Unlike Only a Pawn in Their Game it wasn’t performed in front of a million people in Washington with the great Dr. King waiting in the wings to make what is probably now the most famous speech of the twentieth century. And unlike the Brechtian morality tale The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll, it hasn’t been revived in countless musical guises or been the subject of a potential lawsuit by a rich ‘good ol’ boy’. The song was been played live on just a few occasions in 1963 and ‘64 and once (drunkenly and incomprehensibly) at the Friends of Chile Benefit Concert in May 1974. An outstanding live version features in the film The Other Side of the Mirror, filmed at a ‘workshop session’ at the 1964 Newport Folk Festival. Dylan sits onstage, flanked by a silent Joan Baez, Doc Watson and various old timey hootenanny fiddlers. Like the audience, who have never heard this song before, they are wrapt in astonishment at the story that this scruffy twenty two year is relating. You can, as they say, hear a pin drop…

The song is unique in Dylan’s catalogue in that it is sung from the perspective of a woman. He never attempts to put on a woman’s voice but – as with much of his early work – he sings in a voice that sounds old, worn and weathered by circumstance. It is also one of the few Dylan songs that really examines his own heritage, as well as being his most explicitly anti-capitalist song. Even Ewan MacColl must have approved of this one. The tale is told with great precision in an atmosphere of enticing intimacy. It sounds like an ancient ballad, but tells a relatively modern story set in the Iron Range of Minnesota where Dylan grew up. Although it is called a ‘blues’ it does not use any of the tropes of that musical form. The song is constructed with formal precision, with ten six line verses and no choruses, and has little musical variation throughout. Most of his lines do not rhyme and each verse relies on a rhyme between the third and final lines. This structure helps to emphasise the ‘prosaic’ bleakness of the tale. As usual, Dylan adopts a colloquial tone, using much pararhyme and alliteration. In a couple of places, there are metaphorical expressions, which are made especially powerful by the dryness and tragic stoicism of the speaker’s expression.

THE IRON RANGE

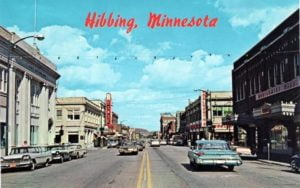

Dylan was still very much under the spell of America’s great ‘people’s champion’ Woody Guthrie when he wrote North Country Blues. Guthrie wrote many songs exposing the effect of capitalism on American workers but he usually included some didactic elements, often suggesting that unionisation is the solution to exploitation. His song 1913 Massacre is about a mining disaster. North Country Blues may be said to have some kinship with Merle Travis’ 1951 song Dark as a Dungeon, a movingly poetic tale of the dangers of mining which even explains how, despite the awful conditions miners work in, they are drawn back to work in them by …the lure of the mine… The song became a folk standard and was movingly performed by Dylan and Joan Baez on the Rolling Thunder Tour and later by Dylan in his Never Ending Tour acoustic sets. But the vast majority of ‘miner’s songs’ came out of coal mining areas such as the Appalachians. Dylan’s song is quite specifically about the open cast iron ore miners of the Mesabi Iron Range which he grew up on, in the town of Hibbing, Minnesota. This is indicated clearly by the title of the song, which echoes that of Girl from the North Country on his previous album.

MOVING THE TOWN

Iron ore was first discovered in Northern Minnesota, in the area immediately south of the Great Lakes, in the late nineteenth century. The area soon became an important supplier for the burgeoning American steel industry in states like Ohio and was later a crucial source of raw materials for the US war effort in the mid 1940s. Ruthless exploitation of workers was indeed rife until the coming of unionisation. It may well be that Dylan’s song is actually set in the early twentieth century, when this kind of exploitation was at its height. Northern Minnesota has a number of ‘ghost towns’; settlements which were hastily erected and then abandoned. One of the most notable is ‘North Hibbing’, the site of the original town of Hibbing. In 1915 the Oliver Mining Company discovered extensive iron ore deposits, under the town itself. Four years later, the entire town of 20,000 people was moved to a location a few miles to the south. Over 200 buildings were moved by means of steel wheels and logs. Some of the remaining buildings in North Hibbing were still standing in the 1950s when Dylan was a teenager. In order to persuade the population to agree to move, the mining company erected several impressive buildings in the ‘new’ Hibbing, including the rather grandiose Hibbing High School, from Dylan graduated in 1959. The school had a large built-in concert hall, at which the teenage Dylan made his first public appearances in his Little Richard-inspired rock’n’roll band The Golden Chords.

HIBBING HIGH SCHOOL

Dylan had an ambivalent relationship with his home town. In his early interviews he claimed to have come from other parts of the country. In Martin Scorsese’s 2005 documentary No Direction Home features he asserts that he was ‘born in the wrong place’. One of the ‘epitaphs’ in The Times They Are a-Changin’s poetic sleeve notes Eleven Outlined Epitaphs describes it as a place for which …I carried no feelings… He refers to the ‘ghost town’ to the north in the mournful lines:

…with its old stone courthouse

decayin’ in the wind

long abandoned

windows crashed out

the breath of its broken walls

being smothered in clingin’ moss

the old school

where my mother went to

rottin’ shiverin’ but still livin’

standin’ cold an’ lonesome

arms cut off

with even the moon bypassin’ its jagged body

pretendin’ not t’ see

an’ givin’ it its final dignity

dogs howled over the graveyard

where even the markin’ stones were dead

an’ there was no sound except for the wind

blowin’ through the high grass

an’ the bricks that fell back

t’ the dirt from a slight stab

of the breeze . . .

The ‘epitaph’ ends with the poet stating that he may return to his home town one day but that that he knows … never t’expect / What it cannot give me…

Dylan’s feelings of dislocation with regard to his home town seem to have contributed considerably to the narrative of North Country Blues. The story in the song is told by a miner’s wife, although that is not made clear until the fourth verse. The tale is so lacking in warmth that one can almost feel the icy wind that …hits heavy on the borderline… as it unfolds. The first verse provides a stark contrast between prosperity and desolation. It begins with a traditional opening of a ballad, as if inviting the listeners to sit with the singer around a welcoming hearth to enjoy some uplifting music: …Come gather round friends and I’ll tell you a tale/ Of when the red iron ore pits ran plenty… But this is immediately undercut by the harshly delineated specific woefulness of ...But the cardboard-filled windows and old men on the benches/ Tell you now that the whole town is empty… The song is not specifically about Hibbing as such, but here Dylan paints a simple but graphic picture of one of the iron range’s ‘ghost towns’.

The next part of the narrative actually reverses the history of Hibbing: …In the north end of town my own children have grown/ But I was raised in the other… We then hear that in …the wee hours of youth… her mother died and that she was raised by her older brother. The third verse is the only one which begins with a rhyming couplet: …The iron ore poured/ as the years passed the door… Then we hear that …the draglines and shovels was hummin’… The rhyming and evocative language suggests that better times are on the way but this is followed by some of the most poignant lines: …’Til one day my brother/ Failed to come home/ The same as my father before him… The terse inclusion of elements of the woman’s ‘back story’ is achieved here with admirable compression, expressed with a kind of dread inevitability.

Things begin to improve. The woman is helped by her neighbours: …My friends they coudn’t-a-been kinder… She later marries a miner. As the years pass, there are more signs of prosperity: …the givin’ was good/ With a lunch bucket filled every season… But then, after she has had three babies, we get the stark …the work was cut down to half a day’s shift with no reason… The rhyming of the hopeful ‘season’ with the bitterly harsh ‘no reason’ is especially subtle and effective here. Then …the shaft was soon shut/ and my work was cut… We may assume she was working in some ancilliary job which was no longer viable because the miners now had no money to spend. This is another example of the care and attention to detail that is apparent in the song, in that Dylan details how working class women in these areas also had to work in order to feed their families.

The narrator then relates the story of the closure of the mine in short, stabbing sentences which convey her incomprehension at the cruel reasoning of the bosses: …the man came to speak/ And he said in one week/ That number eleven was closing… Again internal rhyme is used in a place where it does not occur in the previous verses, but here its effect is harshly ironic. The next verse outlines the ‘explanation’ that the bosses give for the abrupt closure of the mine: …They complained in the East/ They’re paying too high/ They say that your ore ain’t worth diggin’… This is compounded by the dreadful cynicism of …It’s much cheaper down/ In the South American town/ Where the miners work almost for nothin’… Here Dylan uses the disjunctive pararhyme of ‘diggin’ and ‘nothin’ to convey a feeling of extreme dislocation. In these few lines, he also juxtaposes various aspects of American geography – the ‘East’, the ‘South’ and ‘the North’ in a brilliant summary of the exploitative nature of American capitalism. The bosses on Wall Street never even come to the iron range, and thus have no idea of how difficult the lives of their workers are. They seem to have no humanitarian concern whatsoever. This is underlined by their monstrous intention to exploit the even poorer South American workers. One can imagine ‘the man’ speaking to the workers, perhaps stroking his moustache and twirling the pocket watch in his waistcoat, as he grins to himself while happily contemplating the profits to be made from those who will ‘work almost for nothing’. Thus in these sparse lines Dylan conveys not only the cruelty of capitalism within the US but also its even more vicious global outreach.

The last three verses of the song convey the woman’s growing despair, as her relationship with her out of work husband turns sour …So the mining gates locked/ And the red iron rotted/ And the room smelled heavy from drinkin’… The notion of the iron ‘rotting’ is of course metaphoric. In fact it is her marriage that – under the strain of what has happened – is ‘rotting’. The repeated ‘s’ alliteration in the following lines conveys the tension between them: …The sad silent song/ Made the hour twice as long/ As I waited for the sun to go sinkin’… In a very striking image she tells us that …I lived by the window as he talked to himself… suggesting that he is either extremely drunk or suffering from extreme stress. This is followed by the decidedly awkward paradox of …This silence of tongues it was building… She then tells us, in her stoical, unemotional manner, that …Then one morning’s week/ The bed it was bare/ And I’s left alone with three children… We are not told whether the husband has merely left her, killed himself or – most likely – drunk himself into an early grave. The important point is that she has now been left alone.

The final verse is the most tragic of all. So far we have had a narrative of what happened in the past. The woman has lost her father, her mother, her brother and her husband. The whole tale has had an air of terrible inevitability. But now she describes the present, in which – as the harsh winter draws in – the town’s economy is collapsing: …The summer is gone/ The ground’s turning cold/ The stores one by one by one they are foldin’…. Then she projects herself into what seems to be the inevitable future: …My children will go/ As they grow… she muses …For there ain’t nothin’ here now to hold them… Again Dylan contrasts rhyming with pararhyming to convey the terrible disjunctions that have determined her fate. But such an outcome is entirely realistic. The unnamed woman is representative of the many victims of the harshness of unrestrained American capitalism. We admire her for her incredible ability to survive all these personal disasters but the final expression of resignation represents nothing less than the obliteration of hope.

North Country Blues is not an easy song to listen to. But Dylan conveys the awfulness of the woman’s predicament with consummate poetic skill, always maintaining the consistency of the narrative voice he had adopted. In many ways the song is the opposite of Girl from the North Country, which looks back with fond nostalgia on his teenage years in Hibbing and romanticises it as …the North Country fair… It is unlikely that the woman in North Country Blues can even afford …a coat so warm/ To keep her from the howlin’ winds… The two songs demonstrate Dylan’s very mixed feelings about his childhood. In the earlier song he emphasises the wonderful, reassuring warmth that protection against such a harsh environment can provide, whereas in the later song the cold sinks deep into the heart of the narrative itself and never thaws. In North Country Blues, gives us a heartrending portrayal of both his personal feelings about his own childhood, while simultaneously conveying razor-sharp perceptions of the system under which American society in organised. Perhaps this was one song that, even in thirty years of the Never Ending Tour, he felt was too painful to revisit.

DYLAN LINKS

DAILY DYLAN NEWS at the wonderful EXPECTING RAIN

THE BOB DYLAN PROJECT- COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

Leave a Reply