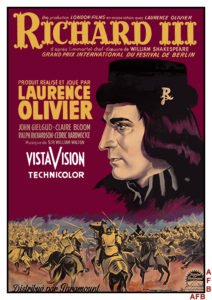

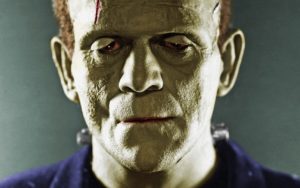

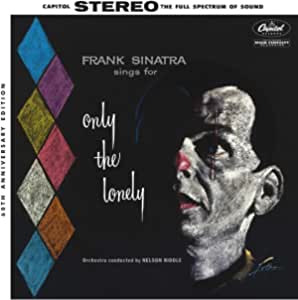

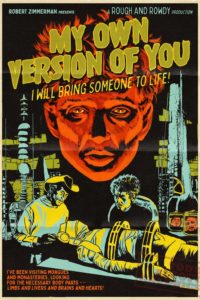

In My Own Version of You Dylan assumes a comic-gothic persona in a song that can be seen as a kind of ‘manual’ for his late period songwriting. By the time Rough and Rowdy Ways was released, the fact that his songs were partly constructed of quotations from and references to other songs, works of literature and even obscure informational texts had become common knowledge. Now he turns this method of ‘reconstruction’ into a far-fetched fantasy full of sharp one-liners. There are echoes of the surreal logic of early comic romps such as Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream or Tombstone Blues, but as the narrator becomes more crazed and meglomaniacal, the song takes on a sombre and ambiguous tone. It is packed with allusions to gothicism, Shakespeare, the Bible and classical literature, along with knowing references to popular culture. With his tongue very firmly in his cheek, Dylan presents himself as a Dr. Frankenstein figure, engaged in a search for ‘body parts’, which he declares that he will soon assemble into a new creation. The music resembles the incidental filler in old horror films or TV shows dealing with ‘unknown forces’ such as The Twilight Zone or The X-Files. The repeated monotonous chord sequence is led by an ominous bass pattern which accelerates towards the ends of verses. In style and tone it also recalls Screamin’ Jay Hawkins’ ‘supernatural’ hell raiser I Put a Spell on You (1956).

SCREAMIN’ JAY HAWKINS

The song has a variable verse and chorus structure, which Dylan uses to build up and release tension. Each two line chorus begins with a variant on the narrator stating his intention to ‘bring someone to life’. The second half of the first line and the second line are different in each case. Two four line verses are followed by three eight line verses, two more four line verses and one final marathon twenty line verse. This unpredictability helps to maintain a distinctly edgy ambience, as we are drawn into the meandering narrative. The first verse immediately establishes the ghoulish ambience. Dylan’s near-whispered semi-spoken vocal and the macabre, alliterative lyrics create an effectively icy ‘mad scientist’ tone. It sounds as if he is licking his lips in anticipation: …All through the summers into January/ I’ve been visiting morgues and monasteries/ Looking for the necessary body parts/ Limbs and livers and brains and hearts… Already we can tell he is up to no good. The first chorus: …I want to bring someone to life – is what I want to do/ I want to create my own version of you… is spookily parodic. The fact that the narrator seems to be addressing a lover, as he does throughout the song, suggests that he is rather desperately deranged. The scenario recalls Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) in which the disturbed protagonist Scottie (James Stewart) attempts to turn a young woman called Judy (Kim Novak) into the dead Madeleine – who he is obsessed with – by making her adopt Madeleine’s clothes and hairstyle.

JUDY/MADELAINE IN VERTIGO

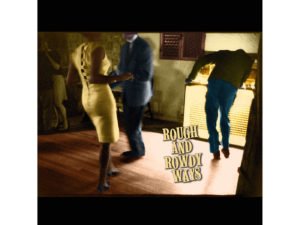

The song includes a couple of very well known Shakespearean allusions. The narrator declares …It must be the winter of my discontent… rephrasing Richard III’s opening speech from Shakespeare’s play. The mention of ‘winter’ reflects on the reference to ‘summers’ and ‘January’ in the previous verse. Richard is a cackling villain, determined to take revenge on the world for cursing him with a physical deformity. He may be stuck in the ‘snows’ of his discontent but the clear implication of his opening statement is that his ‘winter’ will soon be over. Come the spring, he will enact his bloody revenge. The character has been parodied many times, most notably by Peter Sellers, whose hilarious 1964 ‘recitation’ of The Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night imitates Laurence Olivier’s film portrayal of the evil, scheming king (1955). Thus it is hard to take the narrator seriously here, as he is clearly indulging in high melodrama.

OLIVIER AS RICHARD 111 SELLERS AS RICHARD 111

The declaration is followed by a series of vaguely threatening statements …I wish you’d taken me with you wherever you went… is mysteriously beguiling. But soon it is clear that the narrator is becoming ever more paranoid: …They talk all night, they talk all day/ Not for a second do I believe what they say… he tells us, without revealing who ‘they are’. This is reinforced by the next chorus: …I want to bring someone to life, someone I’ve never seen/ You know what I mean, you know exactly what I mean… The music rises in tempo slightly here and Dylan pretends to sound just that little bit alarmed, placing slight emphasis on the word ’exactly’. One is reminded of one of the key lines from Joseph Heller’s hilarious anti war novel Catch 22 (1961), beloved of so many ‘stoners’: …Just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they aren’t after you…

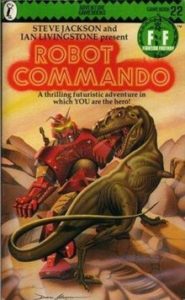

The narrative then spirals into comic absurdity. As the narrator begins to explain how his monster will be put together, Dylan delivers one of his sharpest couplets ever: …I’ll take Scarface Pacino and the Godfather Brando… followed by the deadpan …Mix ’em up in a tank and make a robot commando… This is so funny not only because of the tongue-twisting diction and the outrageous rhyming but because it undercuts the narrator’s supposedly threatening tone so definitively. The gangster films Scarface (1983) and The Godfather (1972) and the performances of their lead actors Al Pacino and Marlon Brando are iconic examples of popular culture. Robot Commando is the name of a children’s toy from 1961 game play book and a tabletop game from 1986. But here the reference seems to be to a ‘transformer’, a popular children’s toy in which one kind of figure can be changed into another, just as the narrator is supposedly threatening to transform his errant lover. The next lines twist this all around even further: …If I do it upright and put the head on straight/ I’ll be saved by the creature that I create… Here the God-like meddling with nature is reduced to the farcical level of the playground.

PACINO, BRANDO AND A ROBOT COMMANDO

The rest of the verse spirals off in strange and apparently random directions as the narrator vows to make use of his new ‘powers of creation’ for magical effects. He makes very spurious claims of being able to get ‘blood from a cactus’ and ‘gunpowder from ice’. The so called ‘blood’ that appears on a cactus is made up of tiny insects that can be crushed to make cochineal. In Jonathan Swift’s great satire Gulliver’s Travels the members of the ‘Grand Academy’ are engaged in trying to make gunpowder from ice. The narrator also tells us that he does not gamble with cards or dice – an unusual claim in a Dylan song. Then he seems to address his ‘monster’ directly: …Can you look in my face with your sightless eye/ Can you cross your heart and hope to die… Perhaps the monster, like Frankenstein’s creation, is only half-finished. ‘Cross your heart and hope to die’ is a common phrase often used by children when they require a friend to pledge allegiance to them. There may also be an allusion here to Shakespeare’s Sonnet XLIII, where the poet enters a dreamy reverie, a world of shadows in which the natural order of things is inverted:

…When in dead night thy fair imperfect shade

Through heavy sleep on sightless eyes doth stay!

All days are nights to see till I see thee,

And night’s bright days when dreams do show thee me…

It now seems as if the narrator may be talking to himself, as if he is looking in a mirror. He is clearly becoming increasingly desperate. He explains that he is trying to bring forth a creation which is a mirror image of himself: …I’ll bring someone to life, someone for real/ Someone who feels the way that I feel… He declares that …I study Sanskrit and Arabic to improve my mind… This is a direct reference to events in the novel, when Victor Frankenstein’s friend Clerval encourages him to study languages to distract him from his obsession with science. The narrator also promises us that …I want to do things for the benefit of all mankind… Thomas Paine’s treatise The Rights of Man (1791), a key text of the Enlightenment and influence on the French Revolution and the Romantic movement, is subtitled For the Benefit of All Mankind. This is also Victor’s stated intention in the creation of his disastrous experiment. The narrator then retreats into a moment of self-pity: …I say to the willow tree “Don’t weep for me’”… ‘Weeping willows’ are a staple of many self-pitying romantic songs, including Blind Boy Fuller’s Weeping Willow (1937), Johnny Cash’s Big River (1958) (in which the narrator claims he …taught the weeping willow how to cry, cry, cry….) and the mournful standard Willow, Weep For Me (covered by Frank Sinatra on the 1958 album Only The Lonely).

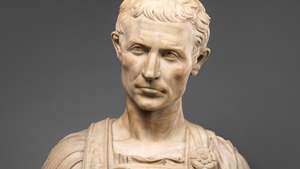

The narrator is now apparently in a state of romantic despair. He has …no place to turn, no place at all… But then Dylan delivers another one of his distinctively gnomic comic utterances: …I pick a number between one and two/ And ask myself ‘What would Julius Caesar do’… Julius Caesar was, of course, no defender of the Rights of Man. His ascension to power brought about the end of Roman democracy. The reference to ‘a number between one and two’ could be read as a somewhat obscure allusion to the binary concept on which all computer operating systems are based. It can also stand as an image of futility, although strictly speaking there are an infinite number of fractions between one and two. Thus the narrator may think he has no options when in reality he has unlimited choices.

JULIUS CAESAR

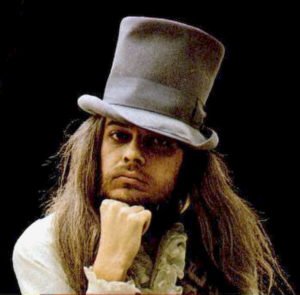

The narrator does, however, seem determined to create – or remake – new life: …I’ll bring someone to life in more ways than one… he tells us in the next chorus …Don’t matter how long it takes, it’ll be done when it’s done… He then proceeds to explain some of the ‘tricks’ he will get his new creation to carry out. Firstly: …I’ll make you play the piano like Leon Russell… Russell collaborated with Dylan on several recordings in 1970-71 and backed him at George Harrison’s Concert for Bangladesh in 1971. He died in 2016, so Dylan may be paying a small tribute here. But then we get a decidedly odd juxtaposition: …Like Liberace, like John the Apostle… The outrageously camp Liberace was a famous piano player and entertainer, while St. John the Apostle was one of Jesus’ disciples and was traditionally thought to be the author of both the Gospel of St. John and the Book of Revelations. He instructs his creation to …Play every number that I can play… and then, with a nod and a wink, throws in …I’ll see you, baby, on Judgment Day… In the lines that follow he extends an invitation …After midnight, if you still want to meet/ I’ll be at the Black Horse Tavern on Armageddon Street… He ends the verse with a casual invitation to this supposedly Satanic location: …Two doors down, not that far to walk/ I’ll hear your footsteps – you won’t have to knock…

LIBERACE AND LEON RUSSELL

Dylan is now thoroughly enjoying teasing us with both Biblical and Shakespearean allusions: …You can bring it to St. Peter, bring it to Jerome/ You can move it all over, bring it all the way home… is another neat series of ‘sacred and profane’ comic juxtapositions. St. Peter was another one of Jesus’ disciples and by tradition the first Bishop of Rome, the forerunner of the Popes. St. Jerome was the first scholar to translate the Bible into Latin. But Jerome is not ‘sanctified’ here and the phrase ‘Bring it to Jerome’ is the title of a song by Bo Diddley (1955) written by his bass player Jerome Green. Its refrain is …Bring it on home, bring it to Jerome… which seems to be referenced in the second line here. Move It All Over (1947) is a comical song by Hank Williams in which an errant husband is refused entry to his house after a drunken evening by his shrewish wife and is forced to spend the night sharing the dog kennel with his hapless hound. The verse ends with …Bring it to me on a silver tray… which may be a reference to the death of John the Baptist, whose head was supposedly presented to King Herod in such a manner.

This is certainly something of a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’ of a verse. In the chorus which follows, however, he keeps a straight face: …I’ll bring someone to life, spare no expense/ Do it with decency and common sense… despite the fact that there is little ‘common sense’ on display here.

BO DIDDLEY, THE DUCHESS AND JEROME GREEN

We are then presented with another well known Shakespearean allusion: …Can you tell me what it means to be or not to be…. As with the earlier reference to Richard III, the lines from Hamlet – in which he questions the very purpose of existence – are recontextualised. The narrator aspires to be a God-like creator but he is as confused as Hamlet about whether life itself is worth living. He asserts that …You won’t get away with fooling me… but we know that he is fooling himself. As his paranoia grows we may well conclude that he is talking to himself – and thus is trying to ‘reassemble himself’. He then makes two rather hopeless appeals: …Can you help me walk that moonlight mile/ Can you give me the blessings of your smile… Moonlight Mile (1971) is a very ‘druggy’ Rolling Stones ballad about how life on the road can drive one to distraction. The reference suggests, if we did not suspect this already, that the narrator himself is not quite in a ‘normal’ state of mind. In the chorus that follows he appears to be taking a breath before delivering the extended denouement of the song. He is concentrating hard now: …I want to bring someone to life, use all my powers/ Do it in the dark in the wee small hours… In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning (1955) is a moody and atmospheric Frank Sinatra track in which he laments the absence of his lover. The reference helps to establish the narrator as a character who is essentially alone and isolated and whose determination to ‘bring someone to life’ is a demented fantasy.

THE TROJAN WOMEN

In the extended final verse the narrator gives full rein to these fantasies, taking us on an impressionistic trip through history in which the events he relates are only really connected through his own mad logic. The opening couplet, with its very memorable rhyme, sets the tone: …I can see the history of the whole human race/ It’s all right there, it’s carved into your face… We may speculate now that perhaps the narrator is addressing some ancient statue – probably of an idealised naked female – fantasising that he can bring her back to life. This ‘gazing into history’ is a prominent feature of Rough and Rowdy Ways, in which the narrators frequently juxtapose elements of ancient and modern worlds. Or perhaps the narrator is merely staring into a mirror, delivering a desperate appeal to himself. He wonders whether he should bow down in subjection: … Shall I break it all down – should I fall on my knees/ Is there light at the end of the tunnel?/ Can you tell me please?…

We are then taken on an extraordinary visionary journey through the ‘history of the whole human race’. We are commanded to …Stand over there by the cypress tree/ Where the Trojan women were sold into slavery… This is a reference to the aftermath of the mythical Trojan war, in events that were depicted in Homer’s Iliad and Euripides’ play The Women of Troy. This is immediately contextualised as being …long before the First Crusade, long before England and America were made… Here the tempo of Dylan’s voice raises a little, as if the narrator is experiencing some kind of feverish dream. We are now being taken well beyond the bounds of the comic juxtapositions of the earlier verses, as we are swept through thousands of years of history. We are led into the darkest place imaginable …Step right into the burning hell… the narrator commands, as if he is the ancient Roman poet Virgil, who appears in Inferno – the first part of Dante’s 14th Century epic The Divine Comedy – as the guide to Dante’s own journey into potential perdition and possible madness. Burning Hell (1959) is, in contrast, a very powerful blues song by John Lee Hooker in which the singer unequivocally denies the existence of either heaven or hell and declares laconically that …When I die, where I go, nobody know…

THE DIVINE COMEDY

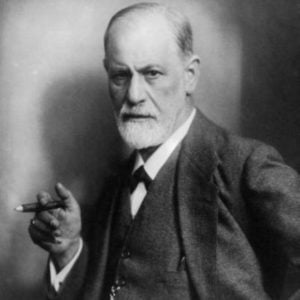

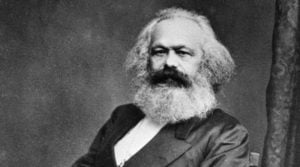

The narrator is taking us into hell for a particular purpose – to introduce us to two figures who he presents as humanity’s mortal enemies: …Mister Freud with his dreams, Mister Marx with his axe… He then directs us, with considerable relish, to …See the raw hide lash the skin from their backs… Dylan builds up the picture of a completely crazed narrator here with great intensity, using a series of monosyllables to emphasise the delirium in his voice. The insertion of these key historical figures into the narrative in this way is certainly unexpected. We may speculate that the narrator seems to blame all modern ills on the inventors of psychoanalysis and socialist political philosophy. Perhaps he is a raving ‘right winger’. Or maybe, giving that he seems to be mentally disturbed, can it be that he has been subjected to some psychoanalysis himself? It may be that he is now recounting his own dreams. One might certainly wonder what ‘Mister Freud’ himself might make of all this. Karl Marx famously stated that …religion is the opium of the masses… and there is little doubt that the narrator is possessed by a kind of religious mania. Both Freud and Marx were (like John Lee Hooker in Burning Hell) professed atheists.

MR. FREUD AND MR. MARX

In the climactic lines, the narrator seems to be imagining himself as a God-like figure. As his mania rises to a pitch, here the address seems to be most clearly directed at himself: …You got the right spirit, you can feel it, you can hear it/ You got what they call the immortal spirit… he proclaims …You can feel it all night, you can feel it in the morn/ Creeps into your body the day you were born… He is firing himself up towards the moment at which his act of creation will take place. Now he fully identifies himself with Dr. Frankenstein, declaring that …One strike of lightning is all that I need/ And a bolt of ‘lectricity that runs at top speed… All of this, however, is clearly just a fantasy. The narrator will never create his ‘monster’. In the final lines of the verse he appears to be contemplating murder, or perhaps suicide: …Show me your ribs, I’ll stick in the knife/ I’m gonna jump start my creation into life… The use of ‘jump start’ – a metaphor taken from the method of starting a dormant car battery – reveals that his understanding of the technology required for the creation of life is laughably primitive.

After the long final verse the last chorus is decidedly and quite deliberately anti-climactic: …I want to bring someone to life: turn back the years/ Do it with laughter, do it with tears… Then the song, rather than coming to a juddering climax, merely fades away. The narrator’s mania has now subsided and that he is back on the treadmill of his everyday existence. The first line summarises his intentions and repeats his insistence on taking us back in time, whereas the second emphasises the tragic-comic nature of the song, and of his own situation. The woman to whom the song is addressed cannot, like Judy/Madelaine in Vertigo, be ‘remade’ into the woman he wants her to be. In any case, she has no doubt stopped listening to him long ago.

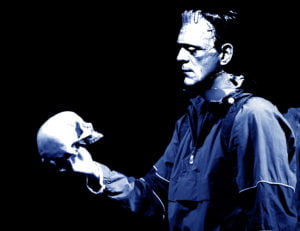

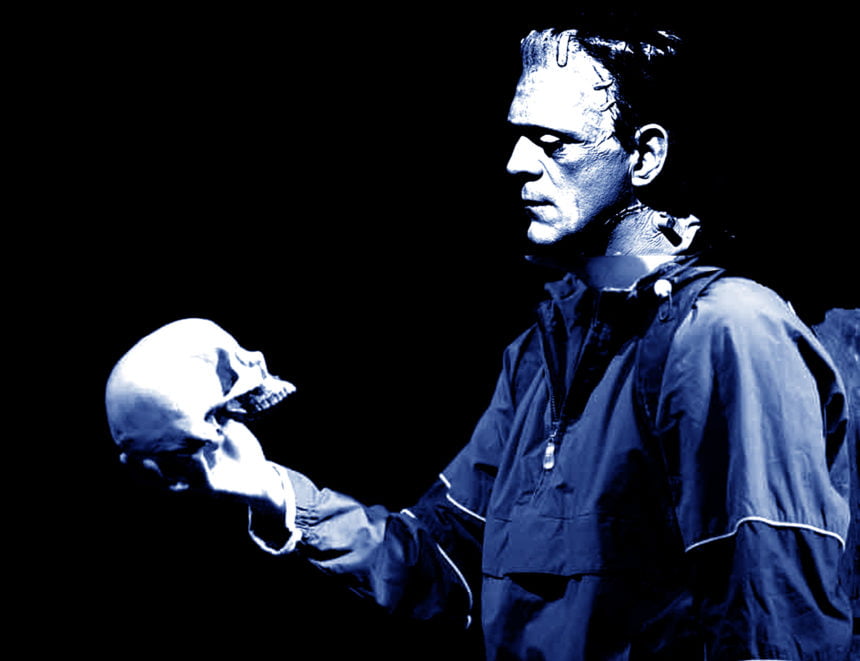

FRANKENSTEIN AS HAMLET

My Own Version of You is one of Dylan’s most effective and ambiguous comic creations. He toys with his listeners throughout, jerking us sometimes violently between comic and tragic perspectives. The narrator may be an amalgam of Frankenstein and Hamlet, fantasising about creating new life but unsure as to whether life is worth living. Or maybe he is some kind of crazed fascistic fanatic, engaging in a Neitzscheian fantasy of bringing to life the first of a ‘super race’. Perhaps he is on ‘a mission from God’ or a servant of the Devil. He may even be a materialist atheist like Dr. Frankenstein himself, who nevertheless tries to ‘play God’. Thus the song may – like Shelley’s Frankenstein itself – be both a warning about the consequences of human scientific aspirations and a cautionary tale about the consequences of both religious and materialistic obsessionalism. However, Dylan’s deadpan delivery suggests that it is, like Desolation Row or The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest, essentially a comic or satirical expression of the dilemmas implicit in the artist’s position as a ‘God-like’ creator. As Polonius comments after one of Hamlet’s most apparently mad (or ’feigned mad’) speeches: …Though this be madness, yet there is method in it…

DYLAN LINKS

DAILY DYLAN NEWS at the wonderful EXPECTING RAIN

THE BOB DYLAN PROJECT- COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

Leave a Reply