.Sleep is like a temporary death…

.

.

“You will perceive that in the breast

The germs of many virtues rest,

Which, ere they feel a lover’s breath,

Lie in a temporary death”

Henry Timrod, Two Portraits

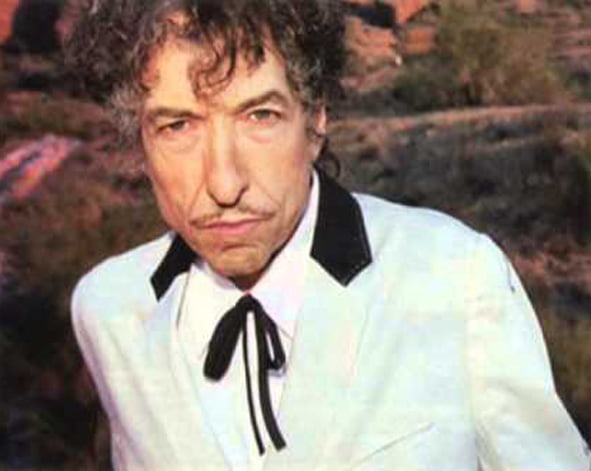

Workingman’s Blues No. 2 is already the most celebrated, though perhaps the most misunderstood, track on Modern Times. Distinguished by a beautiful, shimmering arrangement and heartfelt vocals and crammed with memorable poetic twists, it has an anthemic, always ‘scarf-waving’ quality found in only a few other Dylan songs (Just Like A Woman, The Times They Are A Changin’ and Like A Rolling Stone might be said fit into this category). Without a doubt, it gets you right there. Most of the (overwhelmingly glowing) reviews of the album have already acclaimed it as an ‘instant classic’. It’s the track on the album you might like to play to a non-Dylan fan to try to win them over, to show them that Bob isn’t just this whiny folk singer after all – that he can write a ‘good tune’ and deliver it like a ‘proper singer’ if that’s what he really wants to do. The music and the singing carry the track’s overwhelming mixture of bitter nostalgia and defiant dignity in a way that almost anyone can relate to. As a song it is heart-stoppingly moving. It lifts the spirits. It can make you want to cry. But it is not, as a number of (perhaps hopeful) commentators have suggested, any kind of ‘protest song’. The feelings it conveys are ambivalent, complex, sometimes confused. Positioned at the beginning of ‘Side Two’ of the record, it radically changes the tone of Modern Times. The first five songs are concerned with awaking the spirit of creativity – they are playful and hopeful. Workingman’s Blues No. 2 begins Dylan’s examination of the ‘dark side’ of our Modern Times. Despite its attractive tune and lush presentation, it is the most opaque and ‘difficult’ song on the album.

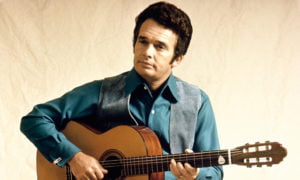

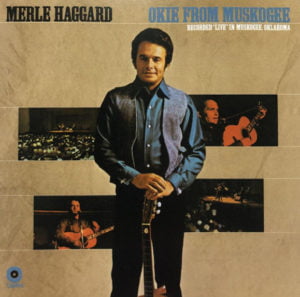

The song is a ‘sequel’ to Merle Haggard’s 1967 celebration of blue-collar pride, Workin’ Man’ Blues. But here Dylan’s rationale is very different to his reworking of blues classics in Rollin’ and Tumblin’, Someday Baby and When The Levee Breaks. His Workingman’s Blues lifts only the chorus line …Sing a little bit of these workin’ man’s blues… While Haggard’s song is a straight twelve bar shuffle, Dylan’s version is not (in the musical sense) a blues at all. Yet it’s clear that any examination of No.2 must start here. Haggard’s narrator is an upstanding member of the ‘proletariat’ (although you won’t, of course, find that word in his song) who has been …a workin’ man dang near all my life… supporting nine kids and a wife with his ‘working hands’. He’s determined to keep working …as long as my two hands are fit to use… and in a pointed sneer at those no good hippies who were getting so much of the limelight at the time, declares (twice in the song, so we can’t fail to get the point) that he ..ain’t never been on welfare/that’s one place I won’t be… But as he sits drinking his beer in a tavern, he does confess that sometimes he does fantasise about doing …a little bumming around… and catching …a train to another town… It is perhaps this part of the song, with its connection to the Woody Guthrie freight-train rambling ethos which originally inspired the teenage Dylan, which provides the clearest link between the two songs. Naturally, Haggard’s narrator’s moment of doubt is quickly excised as he reiterates his intention to ‘keep on workin’ ‘

MERLE HAGGARD

In the late ‘60s a song like Haggard’s Workin’ Man’s Blues would have been seen as terminally unhip. Yet from today’s perspective it is a classic of Americana, and in its own way as much a product of the late ‘60s as the Jefferson Airplane. In this and other songs Haggard was reacting against the spirit of his times by reasserting ‘traditional American values’ but not in a gooey, flag-waving way. The narrator of the song may be proud of his stance, but we are left in little doubt that his life is grueling and unrewarding. He has to keep on working because he has no choice. No doubt he’s in that tavern a lot, downing a great deal of beer. It’s a significant marker of shifts in cultural values that earlier in 2006 we saw Haggard touring in support of Dylan, interspersing his songs with sneering references to Bush’s foreign and domestic policies and comic tales about hanging out and getting very wrecked with his buddy Willie Nelson. Dylan, of course, keeps resolutely mum about such matters. It’s also significant that we can trace the beginnings of such a shift back to the late ‘60s when Dylan himself, then regarded by the counterculture as nothing less than a living prophet, the ‘voice of their generation’, would have no truck with psychedelia. In seclusion in (of all places) Woodstock, New York State, he was creating recordings which, from The Basement Tapes (1967) to the much-misunderstood Self Portrait (1970) (despised by the ‘hippie establishment’ at the time but now standing as an important landmark in the development of ‘Americana’) daringly embraced country music and many of its values. Meanwhile, Dylan’s soulmate in this adventure, Robbie Robertson of The Band, was also involved in creating an imaginative new perspective which incorporated ‘workingmen’s values’ within a vision of what Greil Marcus was later to call ‘the old, weird America’. In Mystery Train, his wonderfully eccentric paean to Elvis Presley and The Band, Marcus calls The Band’s own epic of the ‘working life’ King Harvest (Will Surely Come) (1969) Robertson’s ‘masterpiece’. King Harvest, with its embrace of unionization and its steadfast ‘working man’’s perspective, seems to me to be the other key text we need to look at with reference to Workingman’s Blues No. 2.

Dylan’s begins memorably with his own piano intro to the song’s distinctive melody, underpinned as he begins to sing by Donnie Herron’s understated viola and George Recile’s clipped, military-march style drumming. The voice is warm and resonant, gentle and welcoming. The first image is of sunset: ..an evenin’ haze settlin’ over town/starlight at the edge of the creek… , the words and the singing style creating an idyllic picture. After this, the next lines are perhaps something of a shock, as we are immediately transported into the ‘political’ territory of a kind of ‘Marxist lament’ : …the buyin’ power of the proletariat’s gone down/Money’s gettin’ shallow and weak… Yet Dylan’s delivery remains calm and melodic. The use of the term ‘proletariat’ sounds oddly archaic here, and the sentiment itself strangely nostalgic. We soon learn that the opening image is part of the narrator’s ‘sweet memory’ of a life that has been lost, and so the use of the term seems to be part of that ‘lost world’. At the end of the verse the narrator, still calm and reflective, comments that …they say low wages are a reality/if we want to compete abroad… This is already a widely-quoted couplet, which many commentators have used to suggest that the whole song is a protest against globalization. Despite the fact that it chimes with Dylan’s oft-expressed concern for the American working man, as expressed in his 1983 song Union Sundown (which for all its clumsy rhetoric really was a protest against globalization), his 1994 collaboration with Willie Nelson Heartland and most famously mouthed in his highly controversial comments at Live Aid in 1985 which led to the annual Farm Aid concerts, little of the rest of Workingman’s Blues No. 2 actually supports this claim. In fact, the narrator delivers the lines with a sense of acceptance – there is no real anger here.

The backdrops against which the narrator sings are constantly shifting. As with many of Dylan’s recent songs, it’s hard to figure out whether the action is taking place in the present day or in some past time. Sometimes we seem to be in the present day, sometimes in the 1950s, the 1930s… sometimes as far back as the American Civil War. The narrators of many of the songs on Love and Theft and Modern Times live in a kind of timeless dreamworld. Dylan has said that his ambition is to write songs which ‘stop time’. We are never sure whether the actions he describes are happening in a chronological sequence or not. The songs’ stories are told through the unreliable filter of memory. In the next verse we hear that the narrator is closing his eyes and …listening to the steel rails hum… suggesting he is now a vagrant, riding a freight train. But not because, like Haggard’s working man, he seeks the freedom of ‘bumming around’. Like the migrant workers of the depression, he has no choice. The whole song can be seen as a kind of dream vision seen through this dispossessed working man’s eyes. The great irony of the song is that he is no longer a working man at all. His work has been taken away. The hunger he is fighting to stop …creeping its way into my gut… may be real hunger, or a hunger for ‘what has been lost’. In any case he sounds tearful, and resigned to his fate, telling us he has hung up his ‘cruel weapons’. The love object he addresses, whom he implores to …come sit down on my knee… may well be a child who has now grown up. In his tearful vision the narrator remembers the child as they were when he was raising him or her. He wants to enfold the child with love. But his mind is continually restless. For like the narrator of King Harvest he’s a ..union man all the way… In his mind, there are still battles to be fought. In each chorus he fantasises that, together with his child he will again fight the bosses on the ‘frontline’. The final line of the chorus repeats Haggard’s modest refrain as if it is a sacred call to arms.

As the song progresses the narrator descends further and further into his dream-fantasy. He is an old man, raging against the dying of the light, crying ‘tears of rage’. He imagines dragging those who have dispossessed him down to hell, lining them up against a wall to have them shot. But he is weary, confused, his consciousness …tossed by the wind and the seas… Already he is sinking back into sleep, resigned to his redundancy in this cruel world that has rejected him: …Sometimes no one wants what we got/Sometimes you can’t give it away… As he descends into sleep, dark visions begin to overwhelm him. He …sleeps in the kitchen with my feet in the hall… Of course he has no house, only this tiny freight train carriage where the’ kitchen’ and the ‘hall’ are so close together. He imagines himself confronted by countless faceless enemies, crowding in on him. He knows that death itself is not far away. Sleep is comforting to him but it is …like a temporary death… He knows his death is approaching but he knows not when. In the darkness he feels the …lover’s breath… which in Timrod’s poem will be the force which will awaken the spiritual life within. But it is too late for that breath to work on him. He feels …the night birds call… He knows that the end is nigh. Yet there is no sense of panic, or despair. The music remains stately and unstressed; the band subdued and disciplined behind the singer’s masterful control of his breath.

Increasingly, the narrator becomes a Lear-like figure, exiled from his land and his children. Like the singer in King Harvest he has lost his barn and his horse and his money. He knows that …the sun is sinking… on his life. Like the narrator of that great song of generational anguish Tears of Rage (another song which echoes King Lear, written by Dylan with a melody by The Band’s Richard Manuel) he fears that his child has rejected him. …Of what kind of love is this/Which goes from bad to worse… he asks himself in Tears of Rage. In Workingman’s Blues No. 2 the narrator is even further down the line: …Tell me now, am I wrong in thinking/That you have forgotten me… The narrator tells us that the child has …wounded me with your words… He says that he will wipe the memories of his enemies from his mind, but that the memory of his child – the new ‘working man’ will always remain with him. In the final verses he tries to heal the rift between them – though he is possessed by a disturbingly dark apocalyptic vision of what will happen to the child: …All across the peaceful sacred fields they will lay you low/They’ll break your horns and slash you with steel … he implores his loved one to look into his eyes one final time. And then, as life begins to ebb away, he fantasises that the child will …lead me off in a cheerful dance… Everything will be remade anew… the old man sees himself with …a brand new suit and a brand new wife… He declares that he can live well on a meager diet. In the final moments he restates his pride in being a ‘working man’ by telling us that he is ready to work again, unlike those who …never worked a day in their life/Don’t know what work even means… Perhaps he is Haggard’s working man, now grown old, his world and his values in ruins. But in the end, as the sun sinks on his life, and although circumstances have overwhelmed him, he has something solid to cling to. His pride, in the end, is his salvation.

Although, with its opaque and mysterious surface, the song may appear to be at odds with much of Modern Times, Workingman’s Blues No. 2 is in many ways its central opus. It is a kind of ode to ‘Modern Times’ itself. Not only the modern world of the technological, globalised culture of the twenty first century but also the eternal process of evolving into ‘Modern Times’ that happens to every new generation. And Dylan himself, of course, is a ‘working man’ who for the last eighteen years or so of the Never Ending Tour has pursued the goal of finding his own salvation through constant work. There is a level on which, in Workingman’s Blues No. 2, he is addressing his audience, taking us through the times in which he himself felt abandoned, having only his own pride to fall back on. But the renewed confidence he now shows in his music and his writing – the result of years of hard work – can be felt in every moment of this transcendent, far-reaching piece, which stands with his very best songs. Like Visions of Johanna or Desolation Row or Idiot Wind or Jokerman or Blind Willie McTell it can be subjected to many different interpretations. And like those songs, every time you hear it sets off new trains of thought in your mind. All you need to do is close your eyes and listen to those steel rails humming…

A different version of this text appears in DETERMINED TO STAND: THE REINVENTION OF BOB DYLAN

—————————–

DYLAN LINKS

DAILY DYLAN NEWS at the wonderful EXPECTING RAIN

THE BOB DYLAN PROJECT- COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

THE CAMBRIDGE BOB DYLAN SOCIETY

Leave a Reply