HURRICANE AND JOEY: TWO CINEMATIC NARRATIVES FROM DESIRE

When the album Desire was released in early 1976, many Dylan fans were delighted that, in two of the songs, Dylan appeared to have reverted to the role that made him famous – that of a ‘protest singer’. Both songs were based around the lives of real people and both appeared to rail against the injustice of the American legal system, just as The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll had some twelve years earlier. But whereas the early songs are, in their recorded versions, purely ‘acoustic’ with Dylan on guitar and vocals, these later works feature the Rolling Thunder revue band, in which the eccentric ‘gypsy violinist’ Scarlet Rivera plays a prominent part. The earlier songs, while they may be written from unusual perspectives, are largely didactic. In Only a Pawn in their Game, for example, the murder of black Civil Rights activist Medgar Evers is focused not on Evers himself but on his murderer, who Dylan states ‘ain’t to blame’ because he has been brought up with racist propaganda spread by politicians who tell the poor whites …You’ve got more than the blacks, don’t complain…. In With God on Our Side Dylan gives us a lesson in American history, castigating those who claim to have ‘spiritual authority’ for conducting murderous wars. North Country Blues is an unequivocal attack on the cruelty of American capitalism. Both Hurricane and Joey are, like Hattie Carroll, The Ballad of Donald White, The Death of Emmett Till or Who Killed Davy Moore, songs about real people who are presented as victims of ‘the system’. But here the songs are filtered through layers of ironic narrative presentation. They are both rich in fast moving visual imagery. Like most of the other songs on Desire they can be called ‘cinematic’ songs. In both cases the narrative voices are very much like the ‘voiceovers’ which can be found in popular Hollywood movies. Dylan thus presents us with two supposedly ‘true stories’ which we then have to ‘filter’ through the possible unreliability of the narrators.

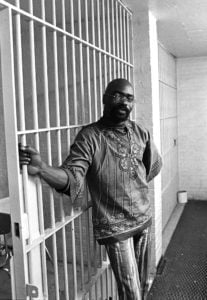

RUBIN ‘HURRICANE’ CARTER

Dylan was sometimes criticised when writing his early protest songs for ‘bending’ or exaggerating the facts of the case. William Zantzinger, who in Hattie Carroll is called ‘Zanzinger’ maintained up until his death that the song portrayed him in an unfair light. In both cases here Dylan idealises the protagonists. Rubin ‘Hurricane’ Carter was a successful middleweight boxer who was imprisoned for murder of three people in a shoot out in a bar in 1966. After he wrote his autobiography, The Sixteenth Round: From Number 1 Contender to Number 45472, (while still in jail), he became a cause célèbre. Many celebrities including Muhammad Ali supported the campaign for his release. Dylan’s song was a successful single and one of the Rolling Thunder Shows, at Madison Square Garden on 8th December 1975, was played as a fundraiser for the campaign. He was subsequently briefly released but was soon imprisoned again. Only in 1985 did his final release occur, when the judge decided that he had been the victim of racial prejudice. Carter’s case remains controversial, with some maintaining that he was indeed a violent criminal while others see him as an innocent victim of a racist American justice system.

Hurricane…

Having read The Sixteenth Round and visited Carter in prison, Dylan declared that he felt a special connection with the boxer and felt that they had similar philosophies of life. The nature of this philosophy was outlined in Carter’s book and in the 1999 movie The Hurricane, which is graced by an outstandingly nuanced performance by Denzel Washington in the title role. Washington powerfully expresses the way in which Carter buried himself in reading and writing as a way of ‘freeing himself’ from the physical boundaries of his prison. Dylan seems to have identified strongly with this devotion to literature and quite genuinely believed in Carter’s innocence. But neither the film nor Dylan’s song can really be said to be unbiased or historically accurate. In both cases, ‘Hurricane’ is romanticised as a character but remains a powerful symbol of resistance against oppression.

Much of Dylan’s attitude to the composition of such songs originated in his devotion to his early mentor Woody Guthrie, who specialised in writing topical ‘anti-establishment’ songs. His Pretty Boy Floyd – which Dylan recorded a compelling version of on a 1988 tribute album A Vision Shared – is the tale of a ‘Bonnie and Clyde’ type figure, based on the character of a notorious bank robber from the 1920s. The song relates how ‘Pretty Boy’ begins his career when he kills a policeman for …using vulgar words of language… in front of his wife. He later becomes a notorious bank robber from the 1920s who turns into a kind of popular hero, frequently helping the poor and providing ….a Christmas dinner for the families on relief… The song ends with some pointedly ironic moralising:

… as through this world I’ve wandered

I’ve seen lots of funny men;

Some will rob you with a six-gun,

And some with a fountain pen.

And as through your life you travel,

Yes, as through your life you roam,

You won’t never see an outlaw

Drive a family from their home…

Thus Guthrie uses what can only be called a morally dubious figure in order to make a point about broader social issues. Dylan used a similar technique in his early protest songs. In the 1964 Halloween Show (released in the Bootleg Series as Live 1964) he introduces Who Killed Davy Moore by declaring …This is taken out of the newspapers… Nothing has been changed except the words… Although Dylan seems somewhat inebriated at the time, giggling as he delivers this line, the point seems to be that one should not necessarily read such songs as ‘historical’ portrayals but as stories in which real life characters are used for dramatic purposes.

The Dylan song which points most obviously to Hurricane is the rather unfairly obscure 1971 single George Jackson, another work which is an idealised portrait of a leading black activist. Jackson was a Black Panther leader and revolutionary writer who, like Carter, was imprisoned, in his case on a relatively minor robbery charge. He was later killed by prison guards during a protest he instigated. Dylan’s song – the first ‘topical’ song he had released since 1964 – relates how the prison guards were …frightened of his power… scared of his love… The song is composed in simple, direct, language but is delivered with great passion, especially in the acoustic version. It ends with a quintessentially Dylanesque couplet with the characteristically paradoxical philosophical statement …Sometimes I think this whole world is one big prison yard/ Some of us are prisoners, the rest of us are guards…

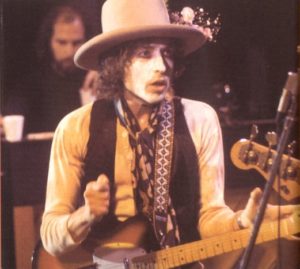

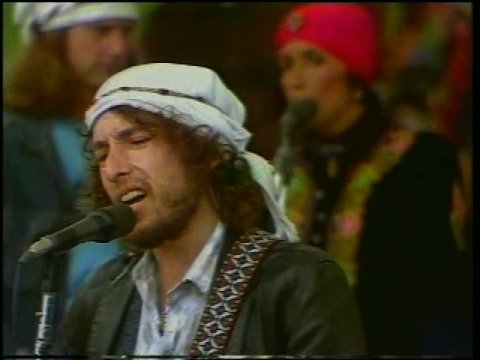

Both Hurricane and Joey, along with most of the Desire album, were co-written with theatre director and film maker Jacques Levy. This was the first time Dylan had co-written a group of songs. He knew Levy’s work from the songs he had written with Roger McGuinn on the late Byrds albums – especially the beautifully ruminative songs on the Untitled album (1970) such as Just A Season, All The Things and Chestnut Mare. Levy went on to become the stage director for the highly theatrical Rolling Thunder tour, which was always intended as the basis for a movie (Dylan’s Renaldo and Clara, released in 1978). It may seem surprising that Levy’s role in song writing (like that of Dylan’s other collaborator Robert Hunter) was that of a lyricist. Why would rock music’s most celebrated lyricist seek such a collaboration? For the purposes of his current project, Dylan seems to have wanted to experiment with his own writing style. He had just achieved a major creative renaissance with the release of his masterpiece Blood on the Tracks, an album of deeply introspective and sometimes bitter songs about relationships. With Desire Dylan was attempting something completely different – upfront, rhythmic and sometimes humorous songs which told stories in a more disciplined way, despite the fact that some of these songs were about real people and apparent injustices

Hurricane is a powerful and direct, but very unconventional, rock song. It seamlessly mixes dialogue spoken by several characters with an overview by an omniscient narrator and uses a series of apparently random line lengths to keep listeners engaged. Despite this, the message it conveys is very clear. It maintains a solid rhythmic drive which accounts for much of its popularity. The song has featured in a number of ‘Greatest Hits’ collections as well as being a particular audience favourite. Many Dylan fans have tried shouting requests for it over the years of the Never Ending Tour, to no avail. It has not been performed live since the end of the first part of the Rolling Thunder tour in 1975. Perhaps this is because it is specifically linked to a time and place, or it may be that Dylan could never come up with an effective new arrangement of the song that would work without the Rolling Thunder band. The studio version is slower with more pronounced vocals. As the tour progresses, the live versions become faster and more frenetic, with Dylan ‘acting out’ the lyrics forcefully behind his whiteface make up. Scarlet Rivera’s slightly wayward but unmistakeable ‘gypsy violin’ provides musical fills between verses. A distinctive ‘galloping’ beat led by Rob Stoner’s chugging bass and percussionist Luther Rix’s frenetic bongos drive the song forward. Ronnee Blakely provides strong backing vocals on the choruses until the song comes to a sudden crashing halt.

This is a remarkable achievement because Hurricane is not an easy song to sing. Very few artists have covered it over the years. It has an unusual verse structure and a very wayward rhyme scheme. A singer has to exercise extremely disciplined breath control in order to perform it. Even the song’s rousing chorus, which begins …Here comes the story of the Hurricane/ The man the authorities came to blame/ For something that he never done/ but one time he could-a been the champion of the world… is something of a tongue-twister. The first two lines are relatively conventional, fitting into the conventional blues structure of eight beats, but already Dylan is cramming in the words, with ‘authorities’ delivered as if it has one, rather than three, syllables. Such ‘cramming’ is a technique frequently used for emphasis by the most skilled blues singers. These lines deliver a fairly obvious rhyme, but in lines three and four rhyme is abandoned. Instead we get the dramatic addition of the declaration …the champion of the world!… delivered with great panache. Dylan extends the last line of a number of the song’s verses but this happens rather irregularly. The effect of the taking of so many liberties with conventional song form is to force the listener to follow the song’s rather complicated and convoluted narrative. Hurricane may be a strongly rhythmic number but you certainly cannot dance to it.

Although the song has a strong chorus, this does not occur at regular intervals. There are nineteen verses but only three choruses. The first chorus comes in after the first verse. We then get seven verses before the next chorus. This is followed by eleven verses before the final chorus, which is slightly changed, with the second and third lines now running: …But it won’t be over ‘til they clear his name/ And give him back the time he’s done… As we wait for the choruses to come, we are drawn inexorably into the narrative.

The first verse sets the scene with cinematic precision. It is written like a film script, with ‘stage directions’, beginning with the highly dramatic line …Pistol shots ring out in the bar room night… a beautifully condensed and dynamic introduction. Then we get …Enter Patty Valentine from the upper hall/ She sees the bartender in a pool of blood/ Cries out “My God, they’ve killed them all!” Here the second and fourth lines are rhymed. But the rhyme scheme will vary in almost every verse. The second verse features rhyming in lines 1, 2 and 4. We hear that Patty sees three dead bodies and ‘a man named Bello’ at the scene. Then we hear Bello’s voice: …”I didn’t do it!” he says, and he throws up his hands/ “I was only robbing the register/ I hope you understand.” This is a most unexpected twist in the story. In the next verse his dialogue continues: …I saw them leavin’, he says and he stops/ “One of us had better call up the cops”…. We are not told whether the presumably bewildered witness believes the word of the ‘small time thief’ but we then hear a similar effect to the last two lines of the chorus, with no rhyming but with the last line greatly extended in a very dramatic and memorably imagistic way: …And so Patty calls the cops/ And they arrive on the scene with their red lights flashing in the hot New Jersey night…

Cue a short dash of gypsy violin. Then we get a verse with four rhyming lines: …Meanwhile far away in another part of town/ Rubin Carter and a couple of friends are drivin’ around/ Number one contender for the middleweight crown/ Had no idea what kinda shit was about to go down… The regularity of the rhyme slows the pace down a little and sounds somewhat reassuring. Here we are introduced to the protagonist, who is merely ‘drivin’ around’ town, completely ignorant of what is about to happen. But in the next verse, the distinct lack of rhyme is something of a shock: …When a cop pulled him over to the side of the road… it begins …Just like the time before and the time before that… The weary-sounding second line makes it quite clear that being pulled up by the police is a common occurrence for any black man who is (as we presume Carter is) driving a ‘flash’ car. The next lines spell this out for us: …In Paterson, that’s just the way things go/ If you’re black you’d better not show up on the street unless you want to draw the heat… The extended final line, with its rather unexpected internal rhyme, is certainly a tongue-twister. We might imagine that this is the voice of Carter himself, acknowledging the racism of the district he lives in.

There is then a cinematic ‘cut’ to the small time robber Alfred Bello who, along with his partner in crime Arthur Dexter Bradley, has …a rap for the cops… This consists of the rather vague …I saw two men running out, they looked like middleweights… This is a sly reference to Carter’s boxing category, as well as a clever depiction of the vagueness of Bradley’s testimony. We then hear that one of the victims is not dead. They take him to the hospital, then …haul Rubin in… for identification but the man cries …”Why d’you bring him in here/ He ain’t the guy!”…

After the second chorus, we get some remarkable lines which put this whole scene into context: …Four months later, the ghettos are in flame/ Rubin’s in South America, fighting for his name… which presumably refer to Carter’s boxing exploits. Meanwhile see how the corrupt police threaten Bradley in order to pin the murder on Carter. We hear that: …The cops are putting the screws on him/ Lookin’ for somebody to blame… The next three verses consists of a dialogue between a crooked policeman and Bradley, as the officer attempts to persuade the small time crook that it would be ‘in his interest’ to testify against Carter. The policeman begins a series of ‘leading’ suggestions by pretending to ‘jog’ Bradley’s memory: …Remember that murder that happened in a bar/ Remember you said you saw the getaway car… Bradley can hardly deny his involvement. As they reveal in later lines about a ‘motel job’, the police clearly have other evidence against him which they are prepared to use unless he can, as they put it …play ball with the law… The verse ends in another long line in which a suggestion is made to Bradley. Here the corruption of the police is made explicit as they deliberately attempt to get him to identify Carter as one of the killers: …Think it might have been that fighter you saw running at night… which is followed by the quite explicitly racist reminder …Don’t forget that you are white…. The implication seems to be that the police are trying to frame Carter and that they hold him in contempt because he is a black man. They are prepared to be lenient with Bradley if he ‘plays ball’ with them. …A poor boy like you… the cop suggests insidiously …could use a break… And later …You don’t want to go back to jail, be a nice fellow…

In the third of these verses, the cop’s corruption becomes explicit: …We want to put his ass in stir/ We want to pin this triple murder on him… is followed by another slyly racist jibe …He ain’t no Gentleman Jim… The reference is the legendary white American boxer of the late nineteenth century James J. Corbett, in the years before African Americans began to dominate the sport. The reference also appears to cast aspersions on Carter’s character, suggesting that he is ‘no gentleman’.

In the final seven verses, we return to the omniscient narrator. The idealisation of Carter now continues. We hear that he does not really enjoy the violence that boxing inevitably involves: …Rubin could take a man out with just one punch… Dylan tells us …But he never did like to talk about it all that much…. Boxing to him is merely a job. He would rather be living in a quiet rural space where …trout streams flow and the air is nice… Then the narrative suddenly shifts. We hear that …then they took him to the jailhouse/ Where they tried to turn a man into a mouse… a rather clichéd line which nevertheless expresses what happens to Carter quite effectively. There is no ambiguity here. …The trial… we are told …was a pig circus… Although the evidence against Carter is very dubious the ‘all white jury’ seems determined to convict him. Dylan throws in a couple of sardonic references to the public reaction to the trial …To the white folks… we are told …He was just a revolutionary bum… And ….to the black folks he was just a crazy nigger… It is certainly ‘crazy’ that Dylan’s use of the ‘n word’ (in the only instance in his entire oeuvre) had led to this explicitly anti-racist song being banned in some quarters. The use of the word here reflects the way it is commonly used by black people to refer to each other. It shows that Carter was not generally seen by the black community as any kind of ‘torch bearer’ for the black liberation movement, emphasising the poisonous power of the media.

As the song comes to a climax, the narrator defends Carter in unequivocal terms, stating that he was …falsely tried… and that he was …obviously framed… in …a land where justice is a game… The final verse presents us with a memorable image of the defiance of injustice which Dylan appeared to have admired so much in the boxer. …All the criminals in their coats and their ties… we are told …are free to drink Martinis and watch the sunrise… This is contrasted with Carter’s great dignity and restraint as he …sits like Buddha in a ten foot cell/ An innocent man in a living hell… As he revealed in The Sixteenth Round, Carter did indeed practice meditation extensively while in prison.

Hurricane is not Dylan’s most ‘poetic’ song. It relies on a number of clichés for its linguistic effects. It also lacks the subtlety of the perspectives Dylan adopts in songs like Only a Pawn in their Game (where the white murderer of black activist Medgar Evars is portrayed not as a monster but as a victim of ‘the system’) or The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll, in which Dylan relates the story of the murder of a black maid with ironic detachment. Written as a didactic song with the express intent of freeing a man whom Dylan had become personal friends with, it is a remarkable example of how song can exploit and incorporate elements of drama and cinema to create a powerful narrative. As with his earlier songs, however, specific historical accuracy is often ignored in favour of dramatic presentation. But the anti-racist message of Hurricane comes over just as powerfully as in those ‘acoustic protests’.

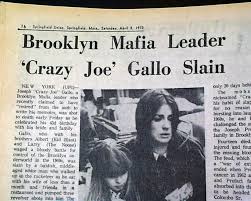

Joey tackles its subject matter in a very different way. On the surface it purports to be, like Hurricane, another lament for a mistreated heroic icon. But while Rubin Carter was certainly a controversial figure, whose story Dylan and Levy may have exaggerated or ‘overdramatised’, Joey Gallo was a prominent member of a Mafia family. Over the years many commentators have railed against Dylan for idealising him. The fact that Joey appears on the same album as Hurricane (on the original vinyl release, each song opens a side of the album) seems to suggest that it is a similar appeal for justice. Other commentators have criticised Dylan for even recording Joey, especially as the brilliantly conceived and executed Abandoned Love was left off the Desire album. Yet Joey is one of the few songs from Desire which Dylan has revisited over the years, with Dylan performing it around 90 times on the Never Ending Tour. It was one of the songs which Dylan began to play while touring with the Grateful Dead backing him in 1987. The song was a particular favourite of Dylan’s great friend Jerry Garcia.

Joey…

Joey is a far more conventionally structured track than Hurricane. It has twelve verses and six choruses. Each verse has an AABB rhyme scheme and there is no attempt, as with Hurricane, to ‘bend’ lines with extra syllables for dramatic effect. The song has an attractive, rather winsome melody. In many ways it is a kind of old fashioned ballad. The repeated chorus hits a pleading note: …Joey, Joey… King of the streets, child of clay/ What made them want to come and blow you away… The recording is also distinguished by Scarlet Rivera’s evocative violin with some colourful interventions on accordion by Dom Cortese. Like Hurricane, the song plays with cliché in places. But while in Hurricane Dylan may have ‘twisted the facts’ a little to suit his didactic purposes, in Joey he appears to have very different intentions. Everything we are told about the mobster is positive. It is suggested that he was not a murderer, that he was somehow drawn into the world of crime against his will. Later he makes friends with black men and protects innocent children. It is also suggested that he is loved by the people of his neighbourhood. But all of this so exaggerated and is obviously romanticised to such an extreme degree that it is impossible to take the song seriously as any kind of historical account. In fact, it can be more accurately seen as a kind of parody of a Hollywood biopic, as if Joey himself was some kind of folk hero whose ultimate murder is a tragedy. In order to appreciate the song it is necessary to separate the real Joey Gallo from the figure that Dylan depicts, who one might picture as the hero of a movie, played perhaps by a handsome ‘square jawed’ Hollywood lead such as Tony Curtis or Kirk Douglas.

AL PACINO AS MICHAEL CORLEONE IN ‘THE GODFATHER’

It is also impossible to ‘read’ Joey correctly without reference to some of the gangster films of the period. The 1970s represented a high point for the American gangster genre, especially in Francis Ford Coppolla’s The Godfather Parts 1 and 2 and Martin Scorcese’s Mean Streets. These richly detailed films were especially distinctive because they treated their anti-heroes as fully realised human beings, whose family lives and relationships are shown alongside their violent ‘day jobs’. In the hands of these brilliant young directors, the films established considerable audience sympathy for their protagonists, despite their roles as murderers and blackmailers. These films also subtly showed that the crime families were very much part of the American political landscape, having influence and control over many corrupt politicians. The character of Michael Corleone (Al Pacino) is a ‘Shakespearean’ figure reminiscent of Macbeth, who is gradually morally corrupted by his involvement with his gangster family. The films can be seen as ‘American epics’, in which flawed characters seek their ultimate destinies by attempting to become ‘heroic’ figures. As in Homeric epics or Shakespearean tragedies, the audience become sympathetic to characters who are often violent, scheming and malevolent as we see their real humanity being eaten away by circumstances. These films thus use the gangster genre as a way of commenting on the nature of much human folly. The fact that the audience often sympathises with Coppolla’s characters, despite their ‘evil’ actions, makes the depiction of their inevitable downfalls all the more powerful.

One of the factors which made the Godfather films so appealing was their rather loving and extremely rich depiction of Italian-American culture. The first film begins at an extremely lavish wedding and culminates in a christening in a church. The audience can delight in the portrayals of the verbal expressions, manners and conventions of this culture. In Joey Dylan and Levy take this audience identification to an extreme, portraying Joey as a kind of Homeric hero. While the song is deeply influenced by the Godfather films in its depiction of Italian-American culture, the depiction of Joey is so extremely idealised that the song can be taken as a kind of parody of Hollywood over-romanticisation in general and of the gangster genre in particular. As with the Godfather movies, listeners are invited to sympathise with a mobster here. But Dylan’s song exaggerates Joey’s ‘good qualities’ so much that Joey himself becomes an emblematic figure. It is really stretching credibility to depict Joey as a kind of ‘Pretty Boy Floyd’ or ‘Bonnie and Clyde’ character but in doing so Dylan challenges his listeners to interrogate the nature of the narrative itself. Is this really just a song about a gangster? Or is it an indication of how certain ‘real life’ characters can become mythologised as part of an examination of the ultimately flawed nature of humanity itself.

‘CRAZY JOE’ GALLO

It may well be that the song itself is narrated by a close friend or sympathiser of Joey, who provides a ‘voiceover’ for this skewed ‘biopic’. The narrator tries throughout to persuade us that Joey was a ‘good guy’, a modern, self-effacing hero. This attempt is not always convincing. As in the Godfather films, we are called upon to constantly examine what we are shown from a moral perspective. The first line …Born in Red Hook, Brooklyn, in the year of who knows when… cleverly combines the ‘sense of place’ which is so prevalent in American film and literature with a rather vague, conversational tone. Then we get the overtly sentimental line …Opened up his eyes to the tune of an accordion…. accompanied, in the original recording, by a burst of accordion. The remaining lines of the first verse again appear to come from the mouth of a close friend of the murdered protagonist: …Always on the outside of whatever side there was… immediately presents Joey as if he was some kind of countercultural rebel …When they asked him why it had to be that way, “Well,” he answered “Just because…”… This is a typically laconic statement which a movie gangster might well deliver in some morally questionable Film Noir.

As the verses unfold, Joey’s essential innocence is laid on thicker and thicker in every verse, with the narrator tirelessly trying to convince of us the virtuous – indeed, saintly – nature of the subject of the song. While it is acknowledged that Joey and his brothers lived off criminal activities like gambling and ‘running numbers’, the excuse is given that ...it always seemed that they got caught between the Mob and the Men in Blue… as if somehow the Gallos were victims of the nature of American society. The narrator vehemently denies that the Gallos murdered their rival gangsters, who are referred to merely as ‘they’. We are told that the ‘war’ between rival gangs that Joey is involved in begins when ‘they’ try to strangle Joey’s brother Larry. We are told that Joey ventures out to get revenge, heroically …thinking he was bullet proof… At first, things appear to go very badly for Joey’s gang, as they suffer ‘terrible defeats’. Then they ‘take some prisoners’ as hostages but, when one of Joey’s compatriots suggests murdering them by …blowing the place to kingdom come… Joey steps in as a peacemaker, stating that …We’re not those kind of men/ It’s peace and quiet that we require to go back to work again…

We are told that the police …got him on conspiracy, they were never sure who with… suggesting that Joey’s prison sentence was perhaps not deserved. In prison, Joey is depicted as a thoughtful intellectual, who …did ten years in Attica, reading Nietzsche and Wilhelm Reich… He is punished by the prison authorities for being a peacemaker who attempts to prevent a prisoners’ strike. The next verse is perhaps the most evocative in the song …They let him out in ’71, he’d lost a little weight/ But he dressed like Jimmy Cagney and I swear he did look great… Again the conversational tone suggests that the narrator is a close friend of Joey, who clearly shows his admiration for him here. The comparison with James Cagney, the actor whose most notable roles were as gangsters, makes the ‘Hollywood’ connection quite explicit here. We hear that: …He tried to find the way back into the life he left behind/ To the boss he said, “I have returned and now I want what’s mine.”… Joey is merely reclaiming his rightful place in the gangster hierarchy, but the way this is phrased makes it sound like he is thoroughly morally justified in this. By now, if we believe the narrator, we must be convinced that Joey was a thoroughly ‘good guy’. This impression is further intensified by what follows. We hear that …in his later years he did not carry a gun… despite which he apparently remains capable of carrying out robberies. He claims that this is because he is …around too many children/ They should never know of one… By now, it is surely obvious that the narrator is greatly exaggerating Joey’s virtuous qualities. One can almost see his halo shining!

The verse which depicts Joey’s murder is especially evocative: …One day they blew him down in a clam bar in New York… is nicely specific. This is rather cheekily rhymed with a very cinematic ‘point of view shot’: …He could see them coming through the door as he lifted up his fork… We hear that he, rather heroically …pushes the table over to protect his family… before his equally heroic demise as he …staggers out into the streets of Little Italy… One can just imagine the close ups of his face in agony and the dramatic incidental music in the death scene.

JOEY GALLO’S FUNERAL

In the final verses the sentimentality is laid on thick, as …Sister Jacqueline and Carmela and Mother Mary did weep/ I heard his best friend Frankie say “He ain’t dead, he’s just asleep”… These conversational lines are succeeded by the rather beautifully resonant …I saw the old man’s limousine head back towards the grave/ I guess he had to say one last goodbye to the son who he could not save… Ornate funeral scenes, in which the characters arrive in black limousines, are prominent features of the Godfather films. Finally we are treated to the movingly elegiac and highly visual couplet …The sun turned cold over President Street and the town of Brooklyn mourned/ They said a mass in the old church near the house where he was born… The final lines, which clearly come from the mouth of our ‘unreliable narrator’, are highly unsettling. They invoke ‘divine judgement’ for the murder of this ‘saintly’ figure: …Some day if God’s in heaven, overlooking his preserve/ I know the men who shot him down will get what they deserve… The menace in these lines is carefully offset against the song’s lyrical melody, but it remains deeply disturbing. The narrator, who as we have seen is almost certainly one of Joey’s compatriots – a member of his ‘family’ – is vowing revenge. It is clear that Joey’s death will merely be the stimulus for more violence.

Joey may be Dylan’s most misunderstood song. The voice of the narrator has often been misread as being that of Dylan himself. This confusion is perhaps understandable, given that Dylan wrote many ‘protest songs’ – including Hurricane – in which he makes moral points, such as: …The poor white man’s used in the hands of them all like a tool… (Only a Pawn in their Game) or …If God’s on our side, he’ll stop the next war… (With God on Our Side). But to ‘read’ Joey literally is to misinterpret it. By 1976 Dylan was experimenting with many different narrative strategies. In Joey he uses an unnamed narrator who attempts to eulogise a person who in real life was a vicious criminal, drawing us as listeners into a particular mind set, making us sympathise with a morally very dubious character. Dylan is thus engaging in a dramatic strategy. Nobody would accuse Shakespeare of pretending that Macbeth is anything but a vicious murderer. But because his soliloquies are so poetically evocative, we find ourselves sympathising with him. In Joey, unlike Hurricane, there is no intervention by an omniscient narrator who spells out the morality of the song. We are left to puzzle out the narration ourselves. This is perhaps why Dylan has continued to perform Joey over the years. Because of the richness of its language, the cultural homage it pays to American cinematic culture and the way it challenges moral notions, rather than ‘lecturing’ its audience, it remains a song whose many subtleties and moral ambiguities allow it a continuing life whereby it can be delivered with a different emphasis in every performance.

Leave a Reply