The pursuit of and definition of beauty has been one of the major concerns of poets throughout the ages. In perhaps his best known poem, Sonnet 18, Shakespeare asks if it is wise to compare the object of his love to a summer’s day, which despite all its glories will inevitably fade away. But he declares that, even when his lover ages …thy eternal summer shall not fade… Shelley’s Hymn to Intellectual Beauty personifies the spirit of Beauty as giving meaning and purpose to life: ...thou dost consecrate with thine own hues/ All thou dost shine upon of human thought or form… but laments its essential transience, asking … where art thou gone?/ Why dost thou pass away and leave our state/ This dim vast vale of tears, vacant and desolate?…

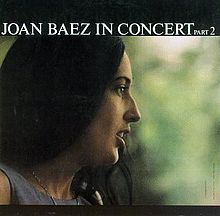

In his early years Bob Dylan produced a number of lengthy compositions which adorned his own album sleeves and those of some of his close compatriots in the folk world. These works were often scatological, full of random thoughts and images and were rarely as carefully written or even ‘poetic’ as his songs. After writing Like a Rolling Stone in 1965 he largely abandoned such efforts, although he was still to produce some pertinent, provocative and witty prose pieces as sleeve notes in future albums. Poem to Joanie, as it is usually known, which first appeared on the sleeve of Joan Baez’s In Concert Vol. 2 (1963), is, along with Last Thoughts on Woody Guthrie, which was read aloud at the end of Dylan’s New York Town Hall Concert in 1963, his most focused attempt at ‘on the page’ poetry, consciously drawing on various poetic traditions. Significantly, both of these long poems are ‘musical’ in form. As well as both being tributes to musicians, they make conscious (if sometimes rather random) use of rhyme schemes and rhythm. Both could conceivably be performed with musical backing.

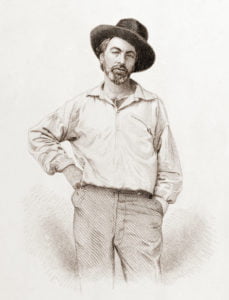

Dylan’s style here is heavily influenced by Ginsberg and The Beats, especially in its heavy use of colloquialisms and attempt to communicate with an audience using heartfelt emotion rather than the technical compression common in modernist twentieth century poetry. As with the poetry of the Beats, the expansive and generous figure of Walt Whitman looms over the work. Poem to Joanie is also very consciously influenced by Romanticism. Its main theme is how the poet, who claims that he had grown up to see value only in harsh depictions of reality, comes to appreciate the value of beauty through his encounter with the astonishing ‘purity’ of the singing of Joan Baez. There are echoes of Byron’s She Walks in Beauty, his seductive description of a very beautiful female, who …walks in beauty like the night/ Of cloudless climes and starry skies… and whose mind is …at peace with all below/ A heart whose love is innocent… On a more philosophical level, Dylan’s poem recalls Keats’ Ode on a Grecian Urn, which reflects that its idealised figures, though long passed away, have achieved a kind of immortality; and famously concludes with the ultimate Romantic ‘manifesto’: …Beauty is truth, and truth beauty/ That is all ye know on earth, and all ye need to know…

The poem has eight verses of varying length and has dome elements of the spontaneous automatic writing favoured by the Beats. But it is carefully structured and very focused on its central themes and concerns. Its remarkably evocative opening verse begins with a decidedly Whitmanesque image of a young boy watching trains go by and rather angrily pulling up the grass and throwing it on the tracks:

…In my youngest years I used t’ kneel

By my aunt’s house on a railroad field

An’ yank the grass outa the ground

An’ rip savagely at its roots

An’ pass the hours countin’ strands

An’ stains a green grew on my hands…

Here Dylan immediately presents us with a vivid symbolic picture. The boy feels a ‘savage’ energy inside himself which he does not really understand. He stares obsessively down at his hands, trying – it seems – to come to grips with his own motivations. We may contrast this with a passage from Whitman’s Song of Myself in which a child presents the poet with a handful of grass. Whitman considers its symbolic qualities:

WALT WHITMAN

…A child said What is the grass? fetching it to me with full hands;

How could I answer the child? I do not know what it is any

more than he

I guess it must be the flag of my disposition, out of hopeful green

stuff woven.

Or I guess it is the handkerchief of the Lord,

A scented gift and remembrancer designedly dropt,

Bearing the owner’s name someway in the corners, that we may

see and remark, and say Whose?

Or I guess the grass is itself a child, the produced babe of the

vegetation.

Or I guess it is a uniform hieroglyphic,

And it means, Sprouting alike in broad zones and narrow zones,

Growing among black folks as among white,

Kanuck, Tuckahoe, Congressman, Cuff, I give them the same, I

receive them the same.

And now it seems to me the beautiful uncut hair of graves….

Thus Whitman turns the grass into a symbol of God’s handiwork in creating natural beauty. Later it becomes a symbol of childhood itself, then of racial equality and then of the naturalness and inevitability of death. One is reminded of Dylan’s line from It’s Alright Ma, I’m Only Bleeding: …To those who think death’s honesty won’t fall upon them naturally/ Life sometimes must get lonely… In Poem to Joanie the boy appears to be filled with anger, which he takes out on the beauties of nature. But in fact he is only ‘killing time’….

…The tracks’d hum an’ I’d bite my lip

An’ hold my grip as the whistle whined

Crouchin’ low as the engine growled

I’d shyly wave t’ the throttle man

An’ count the cars as they rolled past

But when the echo faded in the day

An’ I understood the train was gone…

It is as if the boy has no enjoyment of his own childhood innocence. He seems to be restlessly waiting to grow up, impatiently counting the trains just as he counts the ‘stands’ of grass. Here Dylan marries a wistful Shelleyesque romanticism with the imagery of the blues and country music, in which trains symbolise many things – especially escape from confinement and personal freedom. The boy stares down at the green stains on his hands, which he describes as being like blood. He then looks down at the barren patch of ground he has created and at first feels guilty that he has destroyed a living thing. But then he reasons to himself that:

…“I’m sure the grass don’ give a damn

Anyway it’ll grow again an’

What’s a patch a grass anyhow”…

Then he angrily flings a stone across the railway line. He can, however, still hear the echo of the train …hanging heavy like a thunder cloud… He imagines that its echoes will persist until the next day’s dawn. In the first of a series of rather randomly placed ‘choruses’ he expresses the essential loneliness of the poetic soul which as a child he feels with raw, ‘demonic’ intensity:

…An’ I asked myself t’ be my friend

An’ I walked my road like a frightened fox

An’ I sung my song like a demon child

With a kick an’ a curse

From inside my mother’s womb…

In a 2005 interview in Martin Scorsese’s No Direction Home Dylan explains his rather mystical belief that he was ‘born in the wrong place’. The young Dylan in the poem cannot wait to ‘ride that train’ into his future. Here he claims to be dissatisfied with his life even before he was born, asserting that he possesses a dangerous power, which presumably could – if not properly harnessed – turn him into a destructive person with little regard for the lives of others. He describes his adolescence as one in which this inner ‘demonic power’ began to make him bitter and enraged:

…I backed so far away

From the world’s walls an’ friendless games

That I did not have a word t’ say

T’ anyone who’d meet my eyes…

HANK WILLIAMS

Dylan also describes how, in his childhood embrace of ‘ugliness’, he chooses appropriate heroes who express the dark side of life. He calls Hank Williams, his ‘first hero’, praising his songs about railroad lines which he describes as …filled with stink and soot and dust… Williams’ most celebrated songs like Your Cheatin’ Heart, I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry and Cold Cold Heart are riveting examinations of the pain of heartbreak. Later his ‘idols fall’ when he realises that they are only human like everyone else. Any time he hears words that others think are beautiful, he finds that they …struck my guts but now with a more shameful sound… Later, as a young singer in New York, the only beauty he can find is the …hard filthy gutter sound… which he finds …in the cracks an’ curbs/ Clothed in robes a dust an’ grime…

Dylan then begins to explain the effect of encountering…a girl I met on common ground/ Who like me strummed lonesome tunes… His friends tell him the girl’s voice is ‘lovely’ and ‘a thing of beauty’ but at first he declares that he …hates that kind of sound…:

…The only beauty’s ugly, man

The crackin’ shakin’ breakin’ sounds’re

The only beauty I understand…

He meets the girl and they get on well, but when preparing himself to hear her sing for the first time, a ‘fence’ comes up in his mind as he tells himself there …ain’t no voice but an ugly voice… He declares that, like the stone he threw across those railroad tracks as a young boy, he needs to feel the timbre of the voice with his hand. Thus he is very resistant to accepting the beauty in her voice until he perceives some actual physical effect. Then, in the poem’s shortest verse, which ends in its most devastating line, he gives a graphic description of a horrific incident which the girl tells him had occurred while living ‘in an Arab land’ during her childhood:

…An’ she told me ‘f the dogs she saw

Slaughtered wholly on the street

An’ I learned ‘f how the people’d laugh

As they beat the gentle dogs t’ death…

Here the juxtaposition of innocence – represented by that resonant phrase ‘gentle dogs’ against the ‘ugliness’ of extreme cruelty – strikes a chord in him. The whole of the next verse is a meditation on this story, in which the poet imagines himself as one of the children who tried and failed to hide one of the dogs. He realises that this incident occurred at the same time as him ‘killing’ the grass in the first verse. He is overcome by a strange feeling of guilt, as if the girl’s experience of the awful event is somehow his fault. He experiences a strange kind of transference, in which the two figures’ youthful experiences somehow gel. This causes him to open his mind to listening to the beauty in her voice, although at first he dismisses this from his mind, reiterating that he should …kill those thoughts/ They ain’t no good, only ugly’s understood…

It is in the sixth and longest verse that his revelation occurs. He is sitting on the floor of a painter’s house in the artistic community in Woodstock, smoking and drinking and feeling relaxed. Then, without warning, the girl bursts into pure song, with no musical accompaniment. Although he tries to resist, the ‘wall’ in his mind (previously a ‘fence’) begins to fall:

…all at once the silent air

Split open from her soundin’ voice

Without no warnin’ from her lips

An’ by instinct my blood reversed

An’ I shook an’ started reachin’ for

That wall that was supposed t’ fall

But my restin’ nerves weren’t restless now

An’ this time they wouldn’t jump

“Let her voice ring out,” they cried

“We’re too tired t’ stop ‘er sing”…

Now his resistance is crumbling. He describes how his face ‘freezes’ and the time ‘floated by’. He calls her one of those who have taught him …not about themselves but about me… He laughs a crazy laugh, rests on his elbows and eventually passes out, experiencing ‘unchallenged’ dreams. When he wakes he realises that he had been wrong in thinking that beauty could only be found in ugliness. Now beauty becomes a …magic wand/ That weaves an’ teases at my mind… Listening to the girl’s pure, crystal tones is a ‘Road to Damascus’ moment for him. Many years later, in Chronicles, he describes Baez as singing …in a voice straight to God… Here the feeling he experiences is expressed in random ecstatic imagery, mostly related to different musical instruments:

…For the breeze I heard in a young girl’s breath

Proved true as sex an’ womanhood

An’ deep as the lowest depths a death

An’ as strong as the weakest winds that blow

An’ as long as fate an’ fatherhood

An’ like gypsy drums

An’ Chinese gongs

An’ cathedral bells

An’ tones ‘f chimes

It jus’ held hymns ‘f mystery

An’ mystery’s all too involved…

His only regret is that this revelation has taken so long to happen. In the final verse he states his intention to returns us to the railroad track of his childhood. He pledges not to rip up the grass this time. Instead he will ‘count the strands’ of grass and …pet it as a friend… He will wave at the engineer as the train goes by and shout at him …Tell him Joanie says hello… and delight in the man’s incomprehension. Then, recalling his younger self as a rock-throwing ‘devil child’, he pledges that he will still …sing my song like a rebel wild… but that he will no longer cause ‘hurt’: …Not t’ push, not t’ ache/ And God knows… not t’try… It seems that the epiphany he has experienced when listening to ‘Joanie’ has resolved a deep inner conflict. He no longer feels he has to ‘push’ his way through life and from now on he will no longer be compelled only to seek out ...the crackin’, breakin’, shakin’ sounds…

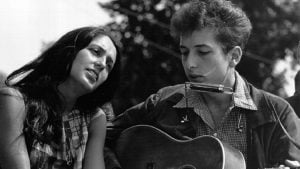

It is ironic that one of the reasons Dylan and Baez parted as a couple was that Baez, having played a part in the Civil Rights movement in the early 1960s, would become increasingly politicised, and was very disappointed that Dylan no longer wished to join her as an activist. Just as Dylan’s experience of Baez seems to have helped him come to terms with his inner ‘demons’, she was inspired by his political songs like With God on Our Side, Masters of War, Blowin’ in the Wind, The Times They Are A-Changin’ and A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall, which she would perform in concert or on political marches. Many of those who found Dylan’s voice too harsh preferred her ‘perfectly’ enunciated renditions of these songs, in which she ‘magically’ transformed the anger that motivated them through her own unique and timeless ‘beautiful’ perspective. Dylan had turned out perhaps the most powerful political songs anyone had ever composed. But after his acceptance of what Shelley called her ‘intellectual beauty’ he lost interest in this kind of material. Their encounter, whatever its romantic implications, thus clearly affected the trajectories of both of their careers. Her liaison with Dylan shifted her from being mainly a purveyor of traditional folk songs to becoming the embodiment of ‘protest’ herself. In contrast, Dylan’s songs that followed – from the Another Side album onwards – were marked by compassion, surreal humour and complex internal examinations of consciousness but eschewed ‘political’ comment. It seems that she absorbed some of his righteous anger while he – through his acceptance of her ‘beauty’ – purged much of that anger from his own heart. Poem to Joanie is Dylan’s most explicit consideration of the value of their relationship to the development of his work. It is also a moving philosophical meditation on the meaning of ‘beauty’ and its significance in art.

DYLAN LINKS

DAILY DYLAN NEWS at the wonderful EXPECTING RAIN

THE BOB DYLAN PROJECT- COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS

THE CAMBRIDGE BOB DYLAN SOCIETY

No comments:

Post a Comment