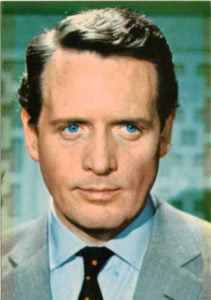

THE PRISONER: PATRICK McGOOHAN

The recent death of the creator of The Prisoner Patrick McGoohan was given surprisingly little publicity. One of those items towards the end of the news where the newsreader adopts an appropriately nostalgic, slightly reverential tone. Some fairly muted obituaries in the newspapers, with the standard shots of McGoohan in his iconic striped blazer as No. 6. … Front page news this was not. The death of John Mortimer, creator of ‘much loved’ courtroom drama Rumpole Of The Bailey seemed to attract more attention. By an odd coincidence the star of Rumpole was the brilliantly garrulous Australian actor Leo McKern, perhaps McGoohan’s most prominent collaborator in The Prisoner. Yet while Rumpole was an intelligently written, entertaining and occasionally challenging series, The Prisoner was much more. It was it a ground breaking, iconoclastic and revolutionary use of the medium of television which managed to hold onto a mass audience even as it became increasingly ‘weird’, morphing from what seemed to be a rather ‘offbeat’ take on the then-prominent Cold War spy genre into a piece of Orwellian, Kafkaesque prophecy and cold-eyed, dark social satire; culminating in the bizarre theatricality and surrealism of its visionary final episodes Once Upon A Time and Fall Out.

In some ways, however, the relative lack of comment is unsurprising. In terms of his public persona and his impact on popular culture, McGoohan was very much a figure of the past. For the past forty years or so he had remained mostly in seclusion in Los Angeles, directing and making guest appearances in a few episodes of Columbo in the late ’70s and making the occasional film appearance – most notably in David Cronenberg’s Scanners (1980) and Mel Gibson’s Braveheart (1996)). Only the rather obscure independent film Kings and Desperate Men, made in collusion with his Prisoner cohort Alexis Kanner in 1981, featured the talents as a writer which had been so clearly showcased in the key episodes of The Prisoner. Over the years, as interest in the seventeen-episode series grew through continual re-runs, widely available DVD box sets and the activities of its own ‘Appreciation Society’, The Prisoner has become established as a televisual classic which now stands out prominently from much of the forgotten morass of 1960s television. Yet sadly there was no significant ‘follow up’ to the series from McGoohan, who found his subsequent ideas for scripts and film projects would be rejected by major film and TV producers as too avant-garde or ‘uncommercial’ for a mass audience. In this way McGoohan can be said to resemble Orson Welles. Like Welles’ Citizen Kane McGoohan’s The Prisoner managed to ‘buck the system’ of the major mass entertainment medium of his day to produce a work that was an extremely quirky, highly challenging, brilliantly realised and highly individual vision. And, as with Citizen Kane, the full impact of The Prisoner only emerged in posterity while its creator languished in increasing obscurity. Just as Citizen Kane influenced generations of film makers around the world by demonstrating the immense artistic possibilities of popular film as medium, so The Prisoner – which marries action/adventure with a philosophical fable for our times – became seen by subsequent TV ‘auteurs’ as a model for what a TV series could achieve. The makers of sophisticated modern series such as Lost have paid explicit tributes to The Prisoner, citing it as a key influence.

In some ways, however, the relative lack of comment is unsurprising. In terms of his public persona and his impact on popular culture, McGoohan was very much a figure of the past. For the past forty years or so he had remained mostly in seclusion in Los Angeles, directing and making guest appearances in a few episodes of Columbo in the late ’70s and making the occasional film appearance – most notably in David Cronenberg’s Scanners (1980) and Mel Gibson’s Braveheart (1996)). Only the rather obscure independent film Kings and Desperate Men, made in collusion with his Prisoner cohort Alexis Kanner in 1981, featured the talents as a writer which had been so clearly showcased in the key episodes of The Prisoner. Over the years, as interest in the seventeen-episode series grew through continual re-runs, widely available DVD box sets and the activities of its own ‘Appreciation Society’, The Prisoner has become established as a televisual classic which now stands out prominently from much of the forgotten morass of 1960s television. Yet sadly there was no significant ‘follow up’ to the series from McGoohan, who found his subsequent ideas for scripts and film projects would be rejected by major film and TV producers as too avant-garde or ‘uncommercial’ for a mass audience. In this way McGoohan can be said to resemble Orson Welles. Like Welles’ Citizen Kane McGoohan’s The Prisoner managed to ‘buck the system’ of the major mass entertainment medium of his day to produce a work that was an extremely quirky, highly challenging, brilliantly realised and highly individual vision. And, as with Citizen Kane, the full impact of The Prisoner only emerged in posterity while its creator languished in increasing obscurity. Just as Citizen Kane influenced generations of film makers around the world by demonstrating the immense artistic possibilities of popular film as medium, so The Prisoner – which marries action/adventure with a philosophical fable for our times – became seen by subsequent TV ‘auteurs’ as a model for what a TV series could achieve. The makers of sophisticated modern series such as Lost have paid explicit tributes to The Prisoner, citing it as a key influence.

McGoohan was an Irish-American who, with his clipped, upper class accent and suavely cynical persona nevertheless seemed quintessentially English. It was in England that he made it as an actor, firstly in the theatre and then in the long-running and increasingly quirky British ‘secret agent’ series Danger Man which ran from 1963-1968, making him a household name in Britain. From here on McGoohan could easily have gone on, like his contemporary Sean Connery, to a long and ‘glittering’ Hollywood film career playing edgy,’intelligent’ action heroes. Despite how tempting this must have been, McGoohan had his own agenda, and his own, highly uncompromising, intransigent and often downright belligerent attitude to popular culture in TV and film. He had principles. Principles which must have rather baffled his paymasters, TV moguls such as Lew Grade who viewed TV shows merely as popular entertainment. Towards the end of Danger Man‘s run, McGoohan exerted more and more influence on its production, writing a number of scripts himself and continually insisting that his character John Drake (the basis for the persona he later took into The Prisoner as No. 6) remain ‘the spy with no guns and no girls’, who would succeed through wit and intelligence alone. McGoohan was scathing about the use of what he called ‘sex and all that rubbish’ in popular genre dramas and argued that John Drake should not be seen to be having casual relationships with women as to do so would be irresponsible given the level of danger in his job. Such a comment may have seemed rather bizarre in the midst of the ‘sexual revolution’ of the 1960s but in retrospect both Danger Man and The Prisoner now seem very sensibly respectful towards women while the contemporary James Bond series looks rather nastily (if sometimes laughably) misogynistic.

Sticking to these principles, McGoohan twice turned down the extremely lucrative offer of playing the role of James Bond. Instead he preferred to move on from Danger Man to create a series in The Prisoner in which he could express his own specific concerns about what he saw as the squeezing out of individuality and a growing culture of mindless conformity in contemporary society, cleverly disguised as a ‘spy thriller’. The series centres around a British spy who (after his resignation from the service) is kidnapped by an unknown organisation and held captive in a bizarre location known only as ‘The Village’ populated by former spies and officials from around the world. In the early episodes the eponymous hero tries various unsuccessful attempts to escape before eventually putting his efforts into subverting The Village itself. As in Orwell’s 1984, The Village is a society in which every citizen is under constant surveillance by cameras – the TV watches you rather than you watching it. Yet while Orwell’s vision of the future is grey, monotonous, impoverished and bleak – what Orwell’s hero Winston Smith refers to as’ a boot stamping on a human face forever’ – the residents of The Village are well fed, well dressed in smart, colourful, informal ‘uniforms’ and superficially happy with their lot, left to enjoy innocent pleasures as long as they conform. Residents are known only by their alloted numbers, not their names, which have been ‘forgotten’ in this supposed utopia. In reality The Village maintains control over all its residents by a regime of mind-control involving brainwashing, torture and the use of new computer technologies and psychotropic drugs. The system is one of totalitarianism with a smiling face, characterised by the Village’s cheery public address system which markedly resembles the mindlessly superficial blandness of similar systems used in Butlins and other holiday camps of the day. Throughout the series our hero – who we know only as ‘Number 6’ – has to resist the many attempts which The Village makes to ‘break’ him, to make him like the other citizens, whom Number 6 contemptuously refers to as ‘a row of cabbages’. As Number 6, McGoohan radiates anger and defiance. His refusal to explain the reasons for his resignation to his captors becomes symbolic of the individual’s defiance of society’s strenuous attempts to make him conform.

The Prisoner is thus an allegorical story and one which has many resonances with contemporary society and political culture. Much of its appeal to contemporary audiences today lies in its prophetic satirical vision of a future Britain which has – particularly under the rule of ‘New Labour’ in the last decade – come to pass. The chatty, informal , self-deprecating personal style of the ever-changing ‘Number 2s’ who rule The Village bears an uncanny resemblance to that of ‘call me Tony’ Blair and his acolytes and successors. Under ‘New Labour’ Britons have become subject to a regime of surveillance which covers virtually all its public spaces – town centres, roads, railway and bus stations, shops, libraries, cinemas, concert halls… the list is almost endless. Signs outside shops tell us we must ‘remove hats and headgear’ before entering (as if the wearing of hats is now illegal!). Everywhere we go the cameras watch us. Crazed New Labour bureaucrats dream up schemes whereby every car journey we make is monitored so that the authorities know exactly where we are going at all times. Announcers on trains blandly repeat that ‘CCTV cameras are in place for your security’. Britain, in short, has become The Village. Just as in The Village, our ‘masters’ have become extremely keen to use every form of new technology they can to control and monitor us. There are plans to monitor every phone call, every email… not to mention the centralization of data implied by the creation of New Labour’s ultimate totalitarian fantasy, the National Identity Card. Significantly, the activist organisation opposing the Identity Card is known as NO 2 ID, a direct reference to The Prisoner.

Two incidents I witnessed recently brought home to me just how prophetically accurate McGoohan’s vision was. One was when I attempted to buy a ‘family ticket’ at the entrance to, of all places, Blackpool Tower. I was asked first not for my name, but for my postcode, as if my postcode was indeed ‘my number’. Another time I was standing in a railway station in London. A man was standing on the stairs next to me, rather idly staring into space, when a disembodied voice from above suddenly ordered him to move, as he was ‘blocking the steps’. At first the man ignored the order, before it was barked back at him. Then he looked up, startled, as if suddenly realising that the voice was directed at him. Of course, after that, he moved immediately. The scene was eerily reminiscent of several in McGoohan’s series. In one episode of The Prisoner our hero suddenly finds himself shunned by his fellow residents who keep calling him ‘Unmutual!’. Today he’d probably be arbitrarily given an Anti Social Behaviour Order.

The most shocking thing about all this is the way in which the British population has so quietly acquiesced to this intense level of surveillance and social control. Indeed, you could almost argue that we have brought it on ourselves by our passivity and natural acquiescence. These days, the training starts early…This is a country in which almost every child in the country is forced into a school uniform at the age of four. Until a few years ago school uniforms were only usually imposed in secondary schools. Now even primary schools adopt them as a corporate badge of identity. The change swept through the country unheralded. Who complained? The ease with which the British Government introduced its smoking ban and measures by which anyone ‘seeming to be under 25’ is likely to be ‘IDed’ when attempting to buy alcohol (when the relevant legal age is all of seven years younger) are further examples of the British public’s cowed acceptance of whatever its masters declare is ‘necessary’. Indeed, we seem to actively fetishise surveillance and control – witness the huge popularity of the reversed Orwelllianism of Big Brother and other so-called ‘Reality TV’ shows, where the act of surveillance becomes a national pastime (you can even watch the contestants in these shows as they sleep, just as if you are No. 2 himself!). Then we can take pleasure in controlling the inhabitants by a ‘democratic’ eviction process until only one stupefied ‘victim’ remains. As No. 2 tells No. 6 on his helicopter ride over The Village ‘ we have our own Town Council here. Democratically elected, of course….’ Thus The Prisoner, though it was made over forty years ago now, stands as a brilliantly caustic, funny and very scary picture of our modern life and culture. Though he was influenced by Orwell, McGoohan’s vision is more accurate as a prediction of the future. What McGoohan got especially right was the essential nature of passivity in British culture which he saw as inevitably leading us towards the kind of ‘soft totalitarianism’ which dominates our culture today. ‘A row of cabbages’ indeed…

Soon a new production of The Prisoner is to hit our screens. This will apparently be a six part mini series and has been filmed in, of all places, Namibia. It features an American actor, Jim Caveziel as No. 6 and Ian McKellan as No. 2. Initial reports are promising. For years a Prisoner sequel was mooted and various disparate rumours of film and TV versions abounded. Many of the proposed remakes were quashed by McGoohan, who was naturally protective of the work he will always be remembered for. It is sad that he will not be around to see this new version. Maybe the new production will add further contemporary relevance to the story and even open up the possibility of future Prisoners. Or maybe it will be a mere footnote to McGoohan’s masterpiece. Despite his failure to follow the series with anything equally substantial, The Prisoner will – whatever its contemporary relevance to future generations- always stand as a landmark in television; the first time the medium of the TV series was used to express a clear authorial vision and a personal philosophy. Its imagery, set design and use of locations – particularly the Portmeirion Hotel in North Wales – have become iconic. And some of its key phrases have survived as still-powerful statements of defiance against the attacks on personal liberty which ‘our masters’ have seen fit to impose upon us. In particular, No. 6’s most famous declarations are ones we might well repeat as we cast those National Identity Cards into the flames where they belong. They also stand as a testament to McGoohan’s own defiant individuality and his refusal to be cowed by ‘the system’. ‘I am not a number’ he tells us, ‘I am a free man!’ And ‘I will not be pushed, filed, briefed, debriefed or numbered. My life is my own!’

————————————————————————————————————–

Leave a Reply