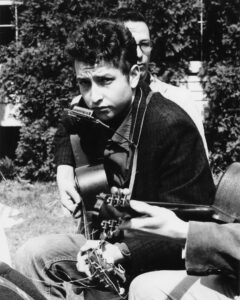

…For three or four years all I listened to were folk standards. I went to sleep singing folk songs. I sang them everywhere, clubs, parties, bars, coffeehouses, fields, festivals. And I met other singers along the way who did the same thing and we just learned songs from each other. I could learn one song and sing it next in an hour if I’d heard it just once…

Bob Dylan, MusiCares Person of the Year Speech. 6th February 2015

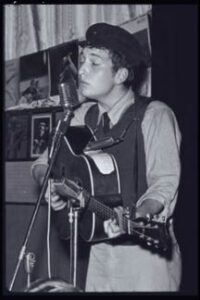

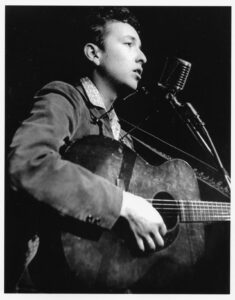

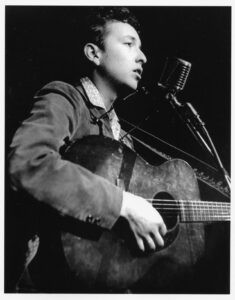

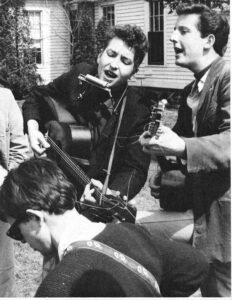

Oscar Brand: November 4th, Saturday Bob Dylan will be singing at the Carnegie Chapter Hall. And that should be a very special occasion. Bob was born in Duluth, Minnesota. But Bob you weren’t raised in Duluth were you?

Bob Dylan: I was raised in Gallup, New Mexico.

Oscar: Do you get many songs there?

Bob: You get a lot of cowboy songs there. Indian songs. That vaudeville kind of stuff.

Oscar: Where’d you get your carnival songs from?

Bob: Uh, people in the carnival.

Oscar: Did you travel with it or watch the carnival?

Bob: Travel the carnival when I was about 13 years old.

Oscar: For how long?

Bob: All the way up till I was 19 every year off and on I’d join different carnivals.

Interview on Oscar Brand’s Folk Song Festival Radio Show 29th October 1961

OSCAR BRAND

Ramblin’ and Gamblin’

Folk music is not so much a body of art as it is a process, an attitude, and a way of life; its distinguishing features lie not within the songs themselves, but in the relations of those songs to a folk culture.

Sam Hinton

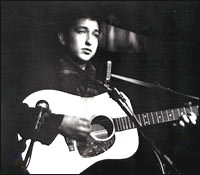

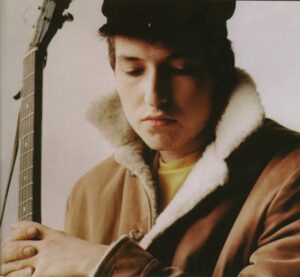

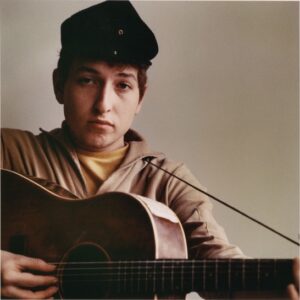

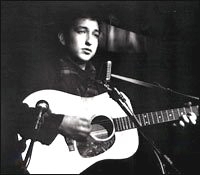

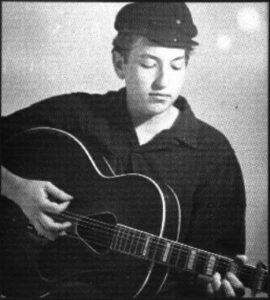

In the years leading up to the release of his ground breaking Freewheelin’ album in 1963, Bob Dylan immersed himself obsessively in many different elements of the folk tradition, from nineteenth century whaling songs to cowboy ballads to lovelorn Scottish laments. Fascinated by the earthy emotions and mysterious undercurrents often found in traditional music, Dylan learned and performed many hundreds of such songs from a wide range of sources. Adopting a vocal style that was the antithesis of the sickly sweet tones of the pop performers who then dominated the charts, he then began to compose his own material. In doing so – following the example of his mentor Woody Guthrie – he adopted the ethos of what was popularly known as the ‘folk process’. This term describes both a method of and an attitude towards song writing that then sustained him throughout his long career.

The ‘folk process’ grew out of practical considerations. Although few of the singers in Greenwich Village were writing their own material at this time, in order to establish themselves as distinctive stylists they frequently developed their own arrangements of traditional tunes. They also often added their own lyrical changes. Thus the line between ‘original’ compositions and adaptations was often difficult to establish. Singer-songwriters who developed their own material through this process were able to delve into the rich store of established folk melodies and use them at will. Such adaptations often had a particular resonance because the ‘new’ songs naturally recalled older songs, so linking the present to the past as part of the continuing tradition. Almost all of Dylan’s early songs were written in this way. As he grew in stature as a song writer he began to modify and change these melodies to suit the nature of his developing concerns.

An outstanding example of how Dylan learned to use the ‘folk process’ is one of his earliest compositions, I Was Young When I Left Home, from 1961. The song uses the melody and many of the sentiments of the traditional 900 Miles, which itself was an adaptation of Rueben’s Train, a popular folk tune of the late nineteenth century first recorded by Fiddlin’ John Carlson in 1924. Dylan performs a highly engaging version on The Basement Tapes. There is only one known recording of I Was Young by Dylan, which was fortunately captured on tape at Bonnie Beecher’s apartment (known as ‘The Hotel’) in Minneapolis on his visit there in December 1961. This was eventually featured on the Bootleg Series’ No Direction Home Soundtrack (2005). It is perhaps surprising that it was not included on his first album as it is a particularly intense and moving performance. An outstanding version by Antony and the Johnsons was recorded for a Dylan tribute album in 2009.

900 Miles is written from the point of view of a ‘lonesome traveller’ who we meet walking alone down a railroad track. Having read a letter from his home, he becomes desperate to return. He offers to pawn his watch, chain and diamond ring in order to get the fare. In Dylan’s song the narrator relates the same basic story, although he makes it explicit that he needs to return after hearing of his mother’s death. Unlike the protagonist of 900 Miles, however, he is very poor and will only be able to return home by pawning his watch and chain when he pays off his debts. He will therefore presumably miss her funeral. The song is also arguably a piece of self mythologising. When Dylan arrived in the Village he frequently told both his contemporaries and interviewers that he had indeed ‘been young when he left home’.

The stories he related usually involved him joining carnivals at a very tender age and travelling around the country. Sometimes he claimed to have met various well known blues singers on the trail and learned specific songs from them. A version of this ‘biography’ even appears on the sleeve notes of his first album. The narrator of I Was Young very much resembles the romanticised hobo figure which Woody Guthrie paints himself as in Bound for Glory and in songs such as Ramblin’ Round or Hard Travelin’ (both of which Dylan performed in his early Village days).

WOODY GUTHRIE

Whereas the narrator of 900 Miles remains fairly sanguine about his situation, Dylan’s masterstroke here is to slow down the melody, turning it into an achingly sad expression of unfulfilled yearning and emotional dislocation. The narrator confesses that he ...never wrote a letter to my home… and is thus plagued by guilt. Yet we must surely suspect there must have been a reason for him running away from home. He relates a few fleeting memories of how he was treated as a child. Dylan’s use of the present tense to describe past events, his characteristic use of ‘wind’ symbolism and his focus on specific detail is especially evocative here: … I’m playing on a track/ Ma would come and whoop me back… he sings …On them trestles down by old Jim McKay’s … Later he recalls telling his ma that he is …Gonna make me a home out in the wind… But in an extraordinary reversal of this desire for freedom he complains that …I don’t like it in the wind/ Wanna go back home again…

Dylan relies on a similar kind of imagery in Kingsport Town, written in late 1962. This was considered for Freewheelin and eventually included on the first Bootleg Series release. It uses the attractive melody and some of the narrative approach of the traditional Scottish ballad The Lass of Roch Royal, later adapted by Woody Guthrie as Who’s Gonna Shoe Your Pretty Little Feet. The strong traditional melody anchors the song and makes it particularly appealing. It begins …The winter wind is blowing strong/ My hands have got no gloves/ I wish to my soul that I could see/ The girl I’m thinking of… This is another song of regret, narrated by a man who has been chased out of Kingsport, Tennessee by the ‘high sheriff’ for falling in love with a …curly headed dark eyed girl….

In the song’s most memorable verse he asks …Who’s gonna stroke your coal black hair/ And sandy colored skin… which is followed by the remarkable … ….Who’s a-gonna kiss your Memphis mouth/ When I’m out in the wind… Dylan, who had now begun to compose a number of ‘protest’ songs, thus turns it into a kind of statement about prejudice against inter-racial relationships which is not, however, couched in any kind of ‘finger pointing’ way. As with I Was Young, the narrator clearly seems to identify with an ‘outsider’ figure but he does not sugar coat the ‘travelling’ life.

Farewell (or Fare Thee Well) is another ‘travelling song’ which Dylan performed several times in 1963. It is heavily based on The Leaving of Liverpool, a seafarers’ ballad from the nineteenth century in which the protagonist expresses continual regret at having to sail off to the USA while leaving his ‘true love’ behind. Dylan first heard this song, a stirring evocation of the Irish diaspora, being performed by The Clancy Brothers. Farewell’’s narrator tells his love that he will soon be leaving, for some unstated reason, for Mexico or California, presumably by hitch hiking across the continent, as he sings …I still might strike it lucky on a highway going West…

The song is not especially tragic. He promises to write to her to share the experience, telling her that: … As I’m ramblin’ you can travel with me too… Perhaps the most distinctively imagistic lines are …With my hands in my pockets and my coat collar high/ I will travel unnoticed and unknown…. This is perhaps the closest Dylan gets to a straight ‘rewrite’ of a traditional song. The chorus …It ain’t the leavin’/ That’s a-grievin’ me/ But my true love who’s bound to stay behind… is almost identical to the original, and the melody is copied wholesale. The song has, however, been recorded by many other artists, including Pete Seeger, Judy Collins, Dion and Lonnie Donegan.

LONNIE DONEGAN

More Ramblin’

Hard Times in New York Town is a semi-autobiographical account of Dylan’s early experiences in New York. It did not appear on his first album, presumably because the talkin’ blues song Talkin’ New York covered much the same territory. Hard Times is based on the traditional Down on Penny’s Farm, a song about the rough conditions of rural workers first recorded by banjo and fiddle duo The Bently Boys in 1930. Dylan uses the melody of the song and changes the refrain from …It’s hard times in the country/ Down on Penny’s Farm… to …It’s hard times in the city/ Living down in New York Town… He also borrows the …Come ladies and gentlemen, listen to my song… introduction. It is quite likely that early audiences recognised that he was updating a well known song and that Dylan is playing with such associations to increase the ironic effect.

The song is quite comical in a Guthriesque manner, portraying a rather manic world within which the narrator remains steadfastly calm, indicating that Dylan is beginning to fuse such ‘folksy’ sentiments with his own brand of distinctive wit …There’s a-mighty many people all millin’ all around… he sings, lingering on the tongue twisting syllables …They’ll kick you when you’re up and knock you when you’re down… He also employs some colourful, if rather cartoonish, personification. We hear that ‘old New York’ is …a friendly old town… Famous skyscrapers are called ‘old Mr. Rockefeller’ and ‘old Mr. Empire’.

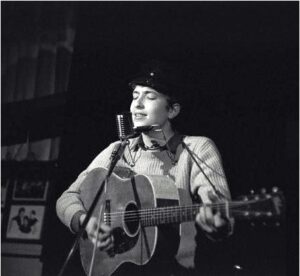

GREENWICH VILLAGE IN WINTER

The river is ‘old Mr. Hudson’. The narrator mixes a certain ironic affection for the city with descriptions of the privations of poverty. Finally he concludes that he must leave, declaring that …I’ll take all the smog in Cal-i-for-ne-ay/ ’N’ every bit of dust in the Oklahoma plains/ ’N’ the dirt in the caves of the Rocky Mountain mines/It’s all much cleaner than the New York kind… Such pan-American celebration of the diversity of the American landscape recalls the ‘people’s patriotism’ of Guthrie’s famous anthem This Land is Your Land.

In a number of other songs, Dylan romanticises the lifestyle of lone travellers. The figure of the loner figures large in many American folk songs, as well as being an image of ‘rugged individuality’ that often features in the Western genre. In developing this theme, Dylan was under the influence of Guthrie’s Bound for Glory as well as that of Jack Kerouac in his poetic travelogue On the Road. Both of these works could be called ‘semi-autobiographical’ in that they built up the image of their creators as distinctively individual, if eccentric, voices. Dylan’s brief vignette Ramblin’ Down Through the World – which is based on Sally Don’t You Grieve, Woody Guthrie’s song about being called up for the army in World War Two – is a cheery declaration of the joys of the travelling lifestyle.

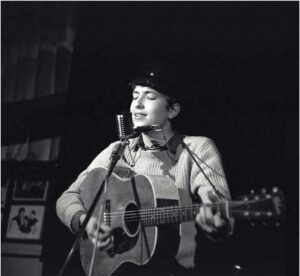

Used as a set opener at Dylan’s first major concert at New York Town Hall concert in 1963, it immediately identifies him with both the ‘freewheeling’ travelling lifestyle and the folk/blues tradition. It has very minimal lyrics, with Dylan merely proclaiming that he is …one of them ramblin’ boys/ Ramblin’ round and making noise/ Sometimes lonely, sometimes blue/ No one knows it better than you… It is mainly a vehicle for Dylan’s virtuoso harmonica playing, which resembles that of harp master Sonny Terry’s distinctive ‘train blues’ sound.

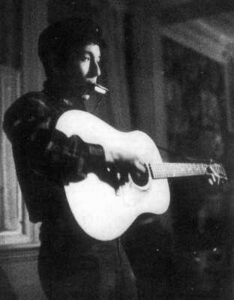

The rather light hearted but fully developed song Dusty Old Fairgrounds, which Dylan only played once, at New York Town Hall in 1963, is an effervescent and highly idealised account of life as a fairground or carnival worker. It is tempting to see it as another piece of self mythologising, as Dylan conjures up the imaginary childhood working carnivals that he had told interviewers and friends about. The melody is reminiscent of the traditional train song Wabash Cannonball, which Guthrie adapted for The Grand Coulee Dam. Here Dylan speeds up the melody in order to fit in the thirteen four line verses; each of which ends in the triumphant cry of …We’re following those dusty old fairgrounds a-calling!… He mostly eschews conventional rhyme, with ‘a-calling’ rhymed with ‘winding’. ‘scrambling’, ‘rolling’ and other ‘ing’ words. The use of these continuous present participles gives the song an entirely appropriate sense of momentum.

The song takes us on a circular tour of the United States, beginning in Florida in the South and then rapidly progressing to the North Country of Michigan. Later we are in Fargo and the Black Hills (North Dakota), Montana, Aberdeen (Washington) and then back to Florida (St. Petersburg). Dylan conveys the excitement of the travelling life with great gusto. He also employs a number of memorable verbal constructions, some of which use internal rhyme, such as …Like a bullet we’ll shoot for the carnival route… …Through the cow country towns and the sands of old Montana… …Our clothes they was torn but the colours they was bright… and ..fill up every space with a different kind of face… The narrator is clearly having a great time …Get the dancing girls in front, get the gambling show behind!… he declares happily.

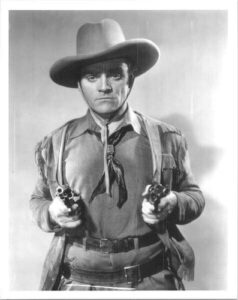

Rambling, Gambling Willie is one of the most fully realised of these early unreleased songs. It was included on the first pressing of Freewheelin’ before being replaced by Bob Dylan’s Dream and was eventually released on the first Bootleg Series set and the Witmark Demos collection. This is another song that romanticises the travelling lifestyle, couched in the form of a cowboy ballad. The fictional Willie O’Conley, an inveterate and ruthless gambler and serial womaniser, is portrayed as a hero, much in the manner of Guthrie’s Pretty Boy Floyd. Dylan was later to write similarly mythologising songs about Western gunslinger John Wesley Hardin(g) and mob boss Joey Gallo. In all of these songs Dylan taps into the American tradition of romanticising outlaws, which is especially prominent in movies, comics, novels and songs about ‘The Wild West’. Ramblin’ Gamblin’ Willie could easily be a kind of ‘treatment’ for a proposed Western movie. One can imagine James Cagney or Humphrey Bogart slipping into the role with ease.

JAMES CAGNEY

The song taps into the tradition of songs about gamblers, portraying them as outsider heroes. Dylan perfomed many such songs, including the traditional I’m a Rambler, I’m a Gambler and The Roving Gambler, in his early club days. Ramblin’ Gamblin’ Willie takes its melody and overall structure from Brennan on the Moor, another traditional Irish song which Dylan first heard being sung by The Clancy Brothers and which itself sentimentalises the story of a notorious highwayman. Dylan even transfers the name ‘Willie’ from the Irish to the American hero.

THE CLANCY BROTHERS

The song has eight four line verses, each of which is followed by the rousing celebratory chorus of …Ride, Willie, ride, roll Willie roll/ Wherever you’re a gamblin’ now, nobody really knows… Dylan begins with an invocation which references one of the older songs: … Come around you rovin’ gamblers and a story I will tell/ About the greatest gambler, you all should know him well… Willie is a loveable rogue who …had twenty seven children but he never had a wife… The song takes us on another tour of the USA, from the White House to a Mississippi river boat to ‘a town called Cripple Creek’ in the Rocky Mountains. In all of these places Willie fleeces the locals with his gambling skills. On the Mississippi he ends up owning the ‘whole damn boat’ and in Cripple Creek, we hear that …nine hundred miners had laid their money down/ When Willie finally left the room, he owned the whole damn town…

In an echo of Pretty Boy Floyd, we are told that Willie is a generous soul with a social conscience who …spread his money far and wide to help the sick and poor… (rather a dubious attribute for a gun slinging gambler) and that …He supported all his children and all their mothers too… Dylan then goes on to describe Willie’s skill in gambling: …When you played your cards with Willie you never really knew/ Whether he was bluffing or whether he was true… and gives an incidence of his opponent folding even though holding a much superior hand. Then the tale comes to its expected tragic end, as Willie is shot in the head by a man whose money he has just won.

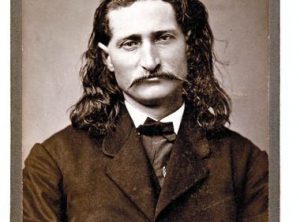

WILD BILL HICKOK

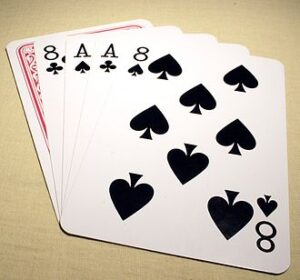

We hear that …When Willie’s cards fell on the floor they were aces backed with eights… a combination known as the ‘dead man’s hand’ which was – according to popular legend – held by the famous gambler and gunfighter Wild Bill Hickok when he was shot in a similar scenario. Finally Dylan explains the moral of the song: …Make your money while you can, before you have to stop/ For when you pull that dead man’s hand, your gamblin’ days are up… so providing a satisfying ending to the tale. In some ways, this lovingly created outlaw figure can be seen as a cipher for Dylan himself – a ‘freewheelin’ figure who faces life with the attitude of a gambler, trusting in providence to see him through. The gambling motif will be used in a number of his songs in future – including the surreal Western spoof Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts (1975) and the sweetly poetic gambling song Huck’s Tune (2006).

In his early days as a songwriter, Bob Dylan established a working method that would do much to help his career take off. The lessons he learned from the composition of these early songs would soon help him create classics such as Blowin’ in the Wind, Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright, Girl From the North Country, Boots of Spanish Leather and A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall, all of which were based on modified versions of traditional folk melodies. In doing so, however, it might be said that he was very much working to his own agenda. The folk revival, which gathered pace in the late 1950s and early 60s in the USA and Britain, was in many ways the product of a yearning for a kind of ‘authenticity’ which was seen as an antidote to what was regarded as the largely anodyne dominance of mainstream commercial music. Some folk purists even insisted that ‘authentic’ performers were only supposed to sing songs from their own area of origin. They also insisted that folk singers should only use acoustic instruments.

Dylan cared little for such concerns. His passion for music had been sparked by the explosion of rock and roll in the mid 1950s. As a teenager he had led a band inspired by Little Richard and only switched to folk when the original spirit of rock appeared to have become diluted and sanitised. Although he immersed himself in the ‘folk process’ he was also heavily influenced by the traditions of blues, country and gospel music, which were rarely hidebound by such limiting ideologies.

When he eventually abandoned being a solo performer he was able to combine elements of the folk process with these other traditions to spellbinding effect. A ‘roving gambler’ by nature himself, he was never afraid to take massive risks with his own career, moving from style to style and genre to genre, riding his luck but always aware that one day he would end up with that ‘dead man’s hand’.

THE ‘DEAD MAN’S HAND’

LINKS

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

THE CAMBRIDGE BOB DYLAN SOCIETY

Leave a Reply