QUEEN JANE APPROXIMATELY

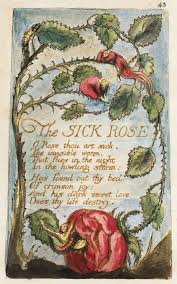

O Rose thou art sick.

The invisible worm,

That flies in the night

In the howling storm:

Has found out thy bed

Of crimson joy:

And his dark secret love

Does thy life destroy.

William Blake, The Sick Rose (1789)

I dream of a red-rose tree.

And which of its roses three

Is the dearest rose to me?

Robert Browning, Women and Roses (1852)

Queen Jane

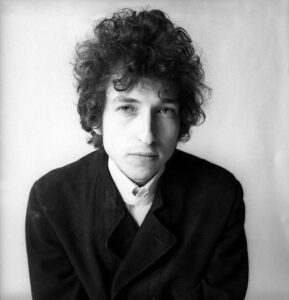

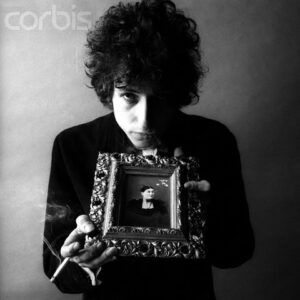

Queen Jane Approximately is an elusive, enigmatic song whose subject is a shadowy figure who may or may not be a real person. Although it appears to be directed at a woman, it can hardly be described as a love song. Dylan’s songs on Highway 61 Revisited are peopled by a range of historical characters, but there is no reason to suggest that the narrator is addressing Henry VIII’s third wife Jane Seymour (the subject of the traditional ballad The Death of Queen Jane) or the briefly enthroned Lady Jane Grey.

JANE SEYMOUR

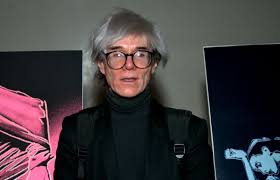

In fact, the naming of the woman as a ‘Queen’ seems to be rather sarcastic. We can, however, imagine that she is some kind of artist or celebrity with a following of sycophants whose advice is not helpful. When an interview asked him who Queen Jane was, Dylan famously replied …Queen Jane is a man… Of course, this response might just be his usual deliberate attempt to lead astray those who try to interpret his songs literally, or try to assert that the song is actually ‘about’ some love interest of his. But the narrator shows no obvious romantic inclinations. The name ‘queen’ can refer to a gay man as well as a female monarch. ‘Queen Jane’ is perhaps as much Allen Ginsberg or Andy Warhol as she is Joan Baez. If she really is a woman, she is only ‘approximately’ so.

ANDY WARHOL

The song was not performed live until 1987, but was played over eighty times between then and 2021. A rather languorous live version appeared on the Dylan and the Dead album. It has been covered by a number of artists but it demands a very special vocal approach – hinting at seriousness but quite cutting in its mockery of its subject. This is a difficult trick to pull off vocally. Various other artists, such as Emma Swift and Bob Weir have produced acceptable versions, but this is a song that requires a particularly seamless mixture of seriousness, humour and self restraint in order to do justice to its uniquely satirical undertones. The most skilful country singers, like Hank Williams, Johnny Cash, Patsy Cline, George Jones and Dolly Parton were expert at combining the expression of emotion with such a self-deprecating tone. Although Queen Jane cannot be labelled a country song, Dylan learned much about the subtleties of vocal expression from such singers. The country-rock singer Lucinda Williams’ 2020 version, which is delivered in her characteristic slightly self mocking drawl, perhaps comes closest to Dylan’s efforts.

As ever with Dylan’s most effective songs, the ambiguity of Queen Jane is its strength. The song is not concerned with the character of Queen Jane herself, of which we learn very little. The entire song deals with others’ reactions to her. There is also little indication as to who the narrator is and what his relationship with her might be, although he does appear to be offering himself as some kind of friend or sanctuary. She may or may not be a famous person who Dylan has only heard or read about and perhaps the entire ‘conversation’ in the song is a mere fantasy. The key elements of the song are the complex emotions and attitudes that the narrator is wrestling with. Some commentators have even asserted that the title character may even be Dylan himself, or the part of him that has become disillusioned with (or bored with) fame.

The entire song consists of an address to ‘Jane’. It has just five verses of five lines each, with the final two lines of each verse consisting of the repeated invocation …Won’t you come see me, Queen Jane?… In many ways it resembles the contemporaneous Positively Fourth Street in that the apparent cynicism of the lyrics is set against a compellingly sweet melody and an easy to sing refrain, which gives it the quality of an infectious pop song. The original recording begins with an attractive piano figure played by Paul Griffin, which acts as a counter melody throughout. This is set against prominent washes of Al Kooper’s organ. Dylan’s vocals are sharp and passionate, as if he is fearlessly cutting through the mystery that the song presents. But he seems to have his tongue in his cheek throughout. The presentation of emotion hovers on the edge of self parody, as Queen Jane can hardly be said to be really suffering. Much of the dark humour of the song is conveyed by Dylan’s judicious use of memorably ironic rhymes.

We are first presented with something of a conundrum: …When your mother sends back all your invitations/ And your father to your sister, he explains/ That you’re tired of yourself and all of your creations… The ‘invitations/creations’ rhyme is especially striking here, with Dylan placing some judicious emphasis on the second word, so communicating a strong sense of ennui. Jane is apparently ‘tired of herself’ and of whatever artistic works she has produced. The narrator appears to be offering her solace from this dilemma. The word ‘creations’ is the only indication in the song that Jane is some kind of artist, although the word ‘creations’ can of course be used in a number of different contexts. Perhaps Jane is some kind of Greek goddess, languishing in boredom on Mount Olympus and looking for excitement. Or perhaps she is a penniless artist or a famous singer or writer. Dylan’s urgent delivery seems to break through some kind of barrier here, as if he is singing directly to her – or perhaps directly into a mirror.

In the following verses Dylan continues to implore Jane to seek his help. He bombards her with unexpected images, beginning with the unforgettably sensual and gloriously vague …When all of the flower ladies want back what they have lent you/ And the smell of their roses does not remain… with its faint echoes of Blake and Browning. The ‘flower ladies’ may be handsome women but their beauty – which they have apparently ‘lent’ to Jane – has now diminished. Perhaps they are figures from a Monet painting which has faded over time. The following …And all of your children start to resent you… with its rather ironic repeated identical rhyme intensifies the sense that the narrator is addressing a rather decadent, self important figure. In the next two verses we hear about Jane’s employees – firstly …all the clowns that you have commissioned… Here, as elsewhere in the song, Dylan surprises us with the juxtaposition of unexpected terms. The fact that the clowns are ‘commissioned’ suggests that they are not really clowns at all but have some kind of ‘official’ status.

Queen Jane…

The next line is perhaps the outstanding example of Dylan’s subtle use of such apparently unrelated terms. We hear that the clowns …have died in battle or in vain… The phrases ‘died in battle’ and ‘died in vain’ normally occur in very different contexts, but here Dylan compresses them, providing them with an equivalent status. This creates a distinctly sardonic twist, underlining our view of Jane as potentially powerful but basically rather decadent. We hear that she is …sick of all this repetition… which itself is an acknowledgement of the song’s repetitious nature. Dylan again places considerable emphasis on the following rhyme, indicating that Jane is simply bored and dissatisfied with her life. It may also be a sly attempt by the narrator to persuade her to ‘come and see him’.

The final two verses continue in a similar vein. We hear how she us surrounded by sycophants who give her what is generally useless advice. This is conveyed by the arresting line …When all of your advisers heave their plastic/ At your feet to convince you of your pain… ‘Heave your plastic’ is another very distinctive juxtaposition. Plastic is a light material which rarely requires ‘heaving’, so this implies that the ‘advisers’ are dumping huge quantities ‘at her feet’. The fact that they have to ‘convince her of her pain’ again strongly suggests that she is not really in any kind of dangerous or difficult situation. This is further emphasised by the next ‘cheeky’ rhyme: …Trying to prove that your conclusions should be more drastic… which again has a heavily satirical tone.

It is clear by now that the narrator is mocking this supposedly ‘regal’ figure. This is further emphasised by the comical reference to …all the bandits that you tum your other cheek to… which rather bizarrely mixes a Biblical symbol of humility with a suggestion that Jane is oblivious to those who might rob from and exploit her. We hear that these bandits, rather than laying down their rifles …lay down their bandanas and complain… These are obviously not real bandits but cartoon versions of Mexican stereotypes from ‘Spaghetti Westerns’. Finally the narrator confides in Jane that he will be there for her if …you want somebody you don’t have to speak to… apparently presenting himself as a friend and confidante. But from his tone, we might suspect he has ulterior motives, which might be interpreted as sexual – or may merely be him continuing to mock her.

Queen Jane….

In 2021 Dylan rerecorded the song with an entirely different melody on Shadow Kingdom, using his latter-day ‘whispering’ vocal style. Although the performance is slower and is tone is much softer, a certain cynical edge is retained. It presents a far more world weary and resigned perspective, suggesting that the existence of ‘Queen Janes’ – spoiled individuals who find even a privileged life to be unsatisfactory – has not diminished. If the song is read as being self reflexive, this indicates that Dylan’s view of such individuals has somewhat softened. There is certainly a strong case for suggesting that Queen Jane is Dylan himself and that the whole song is mocking the pretensions of creative artists who are surrounded by ‘advisers’, ‘clowns’ and ‘bandits’. Alternatively, the song could be seen as one which any one of us could sing to ourselves, in order to gently mock our own flaws.

Leave a Reply