MAN IN THE LONG BLACK COAT – A SCARY SONG?

…We recorded “Man in the Long Black Coat” and a peculiar change crept over the appearance of things. I had a feeling about it and so did he. The chord progression, the dominant chords and key changes give it the hypnotic effect right away – signal what the lyrics are about to do. The dread intro gives you the impression of a chronic rush. The production sounds deserted, like the intervals of the city have disappeared. It’s cut out from the abyss of blackness – visions of a maddened brain, a feeling of unreality – the heavy price of gold upon someone’s head. Nothing standing, even corruption is corrupt. Something menacing and terrible…

Bob Dylan, Chronicles Vol. One (2004)

…Rachel Cooper: Now you remember, children, how I told you last Sunday about the good Lord going up into the mountain and talking to the people and how he said, “Blessed are the pure in heart for they shall see God”? And how he said that King Solomon in all his glory was not as beautiful as the lilies of the field? And I know you will not forget, “Judge not, lest you be judged,” because I explained that to you. And then the good Lord went on to say, “Beware of false prophets, which come to you in sheep’s clothing, but inwardly they are ravening wolves. Ye shall know them by their fruits.”…

Dialogue from Night of the Hunter, script by James Agee, directed by Charles Laughton (1955)

…The boundaries which divide Life from Death are at best shadowy and vague…

Edgar Allan Poe, The Premature Burial (1844)

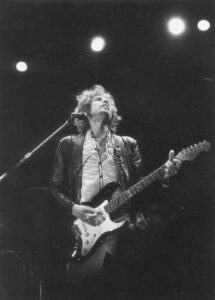

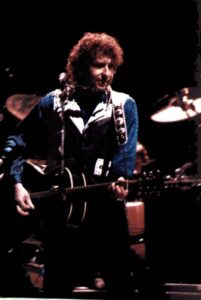

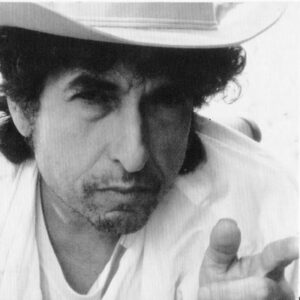

Man in the Long Black Coat is perhaps Bob Dylan’s most haunting creation. It is a song which, through the use of judicious description and highly atmospheric musical application, could be said to create a world of its own. Dylan sketches out the outlines of the story in a highly visual and cinematic manner, leaving us to fill in the gaps with our imagination – and perhaps write our own film script in our heads. The song appears to be set in a mythic realm, a kind of shadowy monochrome version of the Deep South which might be described as a ‘Southern Gothic’ environment. It tells the story of a woman who has apparently run away with a ‘tall dark stranger’.

We are never told who she is (although the lyrics arguably imply that she is respectable and possibly married). The identity of the ‘man’ is also never made clear. Apocalyptic elements in the scenario are hinted at and the voice of a stern preacher is heard, giving the story strong Biblical overtones, although there are no direct Biblical references. It is not made clear whether the woman has been abducted, manipulated or seduced by the mysterious stranger or whether she has left of her own accord.

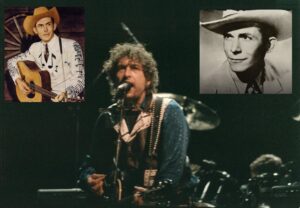

The song conjures up a number of strong associations. It is reminiscent of the short stories of Nathaniel Hawthorne and Edgar Allan Poe, which mingle dark intimations with strongly moral concerns. In some ways the character of ‘the man’ resembles the serial killer and rakish seducer who claims to be a preacher played by Robert Mitchum in the 1955 classic movie Night of the Hunter. There are also echoes of very old folk songs such as House Carpenter (which Dylan recorded memorable versions of in both the Freewheelin’ and Self Portrait sessions) in which a woman leaves her husband and her respectable life for a ‘demon lover’; as well as songs like The Raggle Taggle Gypsies, Gypsy Davy or Willie O’ Winsbury where the woman rides off to live a ‘wild life’ with gypsies. But whether the woman in Dylan’s song is aspiring to the freedom that the women in the latter songs crave or whether she has been ‘possessed’ by ‘the man’ is left for us to decide.

ROBERT MITCHUM IN ‘NIGHT OF THE HUNTER’

In Chronicles Dylan describes how the song was written in New Orleans in one of the night time sessions for Oh Mercy. The original recording conjures up a sweaty atmosphere and a sense of dark foreboding. Daniel Lanois’ radically ‘organic’ layered production techniques do much to create this ambience. The song was recorded in one take, with a few overdubs added later. The only musicians are Dylan on guitar and harmonica and Lanois on various instruments including dobro and omnichord. There is a fairly long intro lasting around a minute. The track begins with what sounds like crickets chirping (as in the first line of the song), which continue in the background throughout. We hear snatches of acoustic guitar, bass and percussion which gradually come together until Dylan comes in with a short harmonica solo. His vocals sound deep and slightly hoarse and he staggers the phrasing by leaving small gaps after every few words, creating a distinctly staccato effect. This gels perfectly with the use of snatches of instrumentation, giving the impression that the narrator is only revealing certain elements of the full picture. The musical form of the song is that of a slow, deathly, waltz – what might be called ‘a dance of the dead’.

The song has four verses and a bridge, all of which are anchored by the title refrain. The rhyming in the song, which follows a simple AABB pattern, is especially distinctive in its use of suggestive irony. The first verse is a brilliant collocation of images which builds up a vivid picture of the scene. We first hear that …Crickets are chirping, the water is high… which immediately places us in the Deep South, perhaps in the Mississippi basin as it recalls the many blues songs, such as Charley Patton’s High Water Everywhere and Big Bill Broonzy’s Terrible Flood Blues, written after the Mississippi flood of 1927.

Already there are hints of an imminent natural cataclysm. This is contrasted against the remarkably simple but resonant image that follows: …There’s a soft cotton dress on the line hanging dry… This dress has presumably been left by the woman who has disappeared, indicating that it has been at least a day or two since this occurred as the dress is now ‘hanging dry’. The rhyme of ‘high’ and ‘dry’ (which in itself is a common phrase indicating abandonment) is a beautifully poised juxtaposition of opposites.

MAN IN THE LONG BLACK COAT

Already we are given a strong visual picture, which is enhanced by more snatches of detail: …Windows wide open, African trees/ Bent over backwards from a hurricane breeze… all of which builds up the sense of an imminent and potentially overwhelming natural disaster. The phrase ‘windows wide open’ again suggests that the occupant of a house has left suddenly. However the mention of ‘African trees’ is rather mysterious. There is no suggestion that we are actually in Africa. Perhaps these are trees such as the Jacaranda, which have been transplanted into various continents. The suggestion of an African connection also creates a possible association with Southern slavery. The description of the trees being ‘bent over backwards’ is especially visual, while ‘hurricane breeze’ is a slightly odd phrase.

Hurricanes are of course devastating events with very high winds which could hardly be described as ‘breezes’. The suggestion seems to be that the breezes are portents of the hurricane to come. We are then told that the woman has left …No word of goodbye, not even a note… and that …She gone with the man in a long black cloak… The use of the colloquial ‘she gone’ hints at the Southern dialect. Here, as elsewhere, the characters are defined more by the absence of particular qualities than their presence.

In the next verse, the narrator switches into ‘hearsay’. We hear that …Somebody seen him hanging around/ At the old dance hall on the outskirts of town… The sighting of ‘the man’ is deliberately vague. We do not know who spotted him, which suggests that we should not necessarily take this account as ‘gospel’. The fact that he is said to be ‘hanging around’ suggests that he is a rather shady character and the location in which he has been spotted being on the edge of town makes the sighting sound even more marginal. We then get ‘up close and personal’: …He looked into her eyes when she stopped him to ask/ If he wanted to dance, he had a face like a mask… It is interesting that it is the woman who instigates the relationship, breaking convention by asking him to dance. There is clearly intimate contact here, but we are given no impression of what ‘the man’ actually looks like. The description of him having ‘a face like a mask’ might be interpreted as intimating that he is adopting a false persona to deceive her. It certainly builds up the mystery surround him.

The verse ends with another mysterious couplet: …Somebody said from the Bible he’d quote/ There was dust on the man in the long black coat… This is another piece of hearsay. All the descriptions of the man seem to be second hand, perhaps throwing doubt on whether he is a real person. We hear that it has been reported that he may be quoting scripture at her, although which part of the Bible he may be referring to is unclear. The remarkable final image, of the man being ‘dusty’ is particularly challenging. Is he in fact a dead man? Or is he actually the Grim Reaper, the personification of death? Has the woman actually died? Or is he some kind of ageless vampire or zombie who has risen from the grave? None of these questions will be answered. From now on we will learn nothing more about him and the circumstances of him eloping with or abducting the woman will remain completely unclear.

Instead of filling us in with these details, Dylan switches tack. We now hear the doom laden voice of some kind of manic preacher who proclaims that …Every man’s conscience is vile and depraved…. and that one’s conscience cannot be relied on as a conductor of one’s life: …You cannot depend on it to be your guide/ When it’s you who must keep it satisfied… thus contextualising the song further, again suggesting the Deep South location. The preacher comes over as a very dark and judgemental figure who appears to be condemning all humanity as sinners, as if he is eagerly poised for the Day of Judgement.

This appears to chime with the earlier apocalyptic warnings of the coming hurricane. We are told that …It ain’t easy to swallow, it sticks in the throat… a double metaphor that relates particularly to the fact that this is a song and that its sentiments are being verbalised. It is also implied that the preacher’s message may be a difficult one to ‘swallow’ but that the ‘doom’ he is predicting will soon be manifested. The line is rhymed with the flat declaration that …She gave her heart to the man in the long black coat… again implying that she is not a mere passive victim but has instigated her departure herself. One might even assume that the preacher and ‘the man’ are the same character, although whether this is true remains uncertain.

The bridge section which follows contains an even more mysterious statement: …There are no mistakes in life, it is true sometimes, you can see it that way… There are, of course, a number of ways that one can ‘see’ the action of this song. The distinctly odd assertion that ‘there are no mistakes in life’ seems to indicate some kind of belief in predestination, but this is filtered through yet more ‘hearsay’. This is followed by perhaps the strangest lines in the whole song: …People don’t live or die, people just float/ She went with the man in the long black coat… We are clearly in metaphysical territory here. The statement that ‘people just float’ seems to imply some kind of belief in reincarnation or eternal life. Perhaps the woman has made a Faustian pact with the Grim Reaper himself. Although ‘the man’ may have whisked her away and murdered her, her soul remains in a kind of ‘floating limbo’.

The song concludes with another series of powerful and resonant images. We hear that …There’s smoke on the water, it’s been there since June/ Tree trunks uprooted, ‘neath the high crescent moon…. The use of the ‘moon/June’ rhyme, which features in so many corny romantic songs, is heavily ironic here. There is certainly no romance to be found, unless the relationship between the woman and the man can be categorised in that way. This, of course, is highly unlikely. The ‘smoke on the water’ appears to be an unnatural occurrence which has remained in place for some time. The uprooted tree trunks again suggest the presence of a hurricane or similar devastation. Then we get perhaps the most devastating lines in the whole song: … Feel the pulse and vibration and the rumbling force/ Somebody is out there beating on a dead horse…

The first, powerfully visceral , line takes us into the heart of the apocalypse. Something is clearly happening here which goes beyond a woman running away with a mysterious man. The whole earth, it seems, is in some kind of convulsion. The second line is in stark contrast, depicting yet another ‘somebody’ engaged in a violent but completely pointless occupation. This recalls the common expression ‘flogging a dead horse’ which indicates a person pursuing a lost cause. The suggestion seems to be that the coming apocalypse is unstoppable. It may be, therefore, that the woman and the man are not real people but merely symbols of an illicit union that will devastate the Earth.

MAN IN THE LONG BLACK COAT

The song ends with the bland and unrevealing …She never said nothing, there was nothing she wrote/ She gone with the main in the long black coat… featuring a very Dylanesque use of the double negative ‘never said nothing’ which can, of course, be taken more than one way. ‘Nothing’, as in The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest, is revealed. As the narrator of Like a Rolling Stone tells us …When you ain’t got nothing, you got nothing to lose… Dylan, of course, loves nothing more than ambiguity. In the work of the symbolist poets, ambiguity is considered essential for making poetry speak in a multi-tongued and ‘magical’ language. Man in the Long Black Coat is a quintessentially ambiguous song which may be describing a mere elopement. On the other hand it may be a symbolic representation of how we may be goaded into a life of sin by those who play devilish tracks on us. As the preacher warns us, our consciences may at any point be compromised by such blandishments.

The song also hints at the possibility that humans can be led by their own folly towards their own self destruction. The man in the long black coat may be Death itself. He may be the Devil. He may symbolise the weapons of mass destruction that could wipe out all life on Earth. He may be a representation of the temptations that we may all face in life. Or he may be just a mere shadow, a body without substance that is the product of our own fevered imagination. The great triumph of this song is that it encompasses all these possible meanings at the same time. As the final harmonica solo fades in and out, we are left staring at the devastated landscape that the song depicts, which may or may not be a reflection of our own consciousness. What the song certainly is, however, is a warning against false or hypocritical religiosity. It depicts not so much the consequences of sin but the consequences of blindly following those whose promises may be alluring but ultimately – like the man in the long black coat – have no real substance.

Leave a Reply