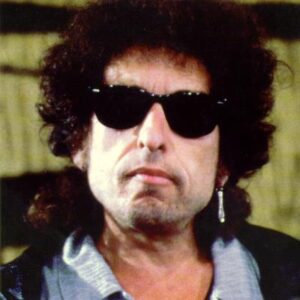

…Sometimes you just have to bite your upper lip and put sunglasses on…

Bob Dylan, Chronicles, Volume One

Bob Dylan is an artist who has ‘reinvented’ himself and his music many times. By the late ‘70s he had presented himself as a Woody Guthrie clone, a solo folk-protest and blues singer, a radical rock revolutionary, a ‘down home’ country singer, a confessional singer-songwriter and a make-up wearing ‘stage actor’. Up until 1979, each of these transformations had a strong effect on the entire landscape of popular music. In some ways his ‘gospel period’ of 1979-80 can be seen as an immersion in yet another authentic form of American ‘roots music’. This latest radical reinvention had, however, divided his followers. Many of them could appreciate the considerable power and fired up apocalyptic fervour of his performances over this period but relatively few were in sympathy with his lyrical approach.

By late 1980, however, it was becoming clear that Bob Dylan’s devotion to ‘Born Again’ Christianity was ebbing away. Having only performed explicitly religious songs in concert since 1979, in his final tour of 1980 he now began to reintroduce his classic material. Although he continued to feature some songs from Slow Train Coming and Saved and allowed space in his shows for his backing singers to perform gospel material, there would be no more on stage ‘sermons’. In August of 1981 he released Shot of Love, an album which mixed some purely secular compositions with a number of often rather troubled ‘post religious songs’. By the time he returned to touring in 1984, he was playing what might well be described as a ‘Greatest Hits’ set with minimal selections from his ‘gospel years’. There has been much debate in subsequent decades as to whether he then retained his Christian beliefs, ‘returned’ to Judaism, adopted a pan-religious attitude or even turned away from such beliefs entirely. In the rare interviews he has given over the years his answers to such inquiries have been characteristically elusive. He continued to refer to Biblical sources in his songs. He had, however, been doing this since his earliest days as a songwriter.

Over the next seven years, Dylan’s reputation as a contemporary force in rock music was to plummet. Having alienated much of his fan base, his record sales and his status as a headlining act went into in rapid free fall. He released a series of badly received albums and towards the end of the decade was being backed up in concert by established bands Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers and The Grateful Dead. In these shows the spotlight appeared to be on his well known compositions from the past rather than contemporary songs. As the decade progressed he seemed to have less and less faith in himself as a songwriter. By the time he released Knocked Out Loaded in 1986 and Down in the Groove in 1988 he did not even have enough new songs to fill the albums. As he later wrote in Chronicles Vol. One …There was a missing person inside of myself and I needed to find him. I felt done for, an empty burned-out wreck…… I had been closing my creativity down to a very narrow, controllable scale…

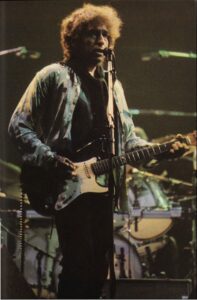

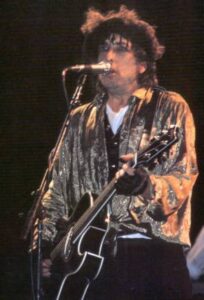

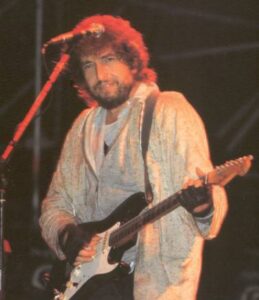

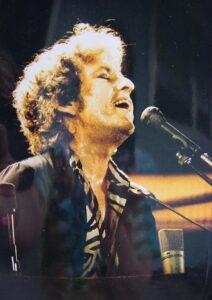

DYLAN WITH PETTY AND THE HEARTBREAKERS

Dylan was not the only singer songwriter who struggled in the early to mid 1980s. Artists like Neil Young, Joni Mitchell and Paul Simon all had problems recording albums in this period, especially with regard to current trends in recording techniques. Leonard Cohen even found it difficult to get a secure recording contract. In the wake of the short lived punk and post-punk eras, a new ‘big haired’ pop aesthetic had become dominant. It seemed that the rock and folk rock styles of ten years before were now passé. Forms of ‘70s dance music such as disco were heavily influential on electronic duos such as Eurhythmics and Soft Cell, not to mention on the burgeoning hip hop scene in America. Pop-soul oriented acts like Michael Jackson, Lionel Ritchie, Madonna and Whitney Houston sold vast amounts of albums. Even innovative songwriters like David Bowie (with his pop-funk album Let’s Dance) and Bruce Springsteen (with his pop-rock mega seller Born in the USA) seemed to be buying into current trends. This was also the era of the dominance of the pop video, especially on the American cable TV channel MTV, in which the messages of songs were often reduced to simplistic semi-cinematic dramatisations which were often remembered more by the fans than the songs themselves.

It was in this cultural environment that Bob Dylan attempted to find a new orientation for his music. Despite his enduring fame and influence, he had always been uncomfortable as a ‘celebrity pop star’, rarely giving interviews and never appearing on TV chat shows. The disparity between the scruffy authenticity of his approach to his art and the pop aesthetics of the decade was thrown into particular relief in 1985 when he was drafted in to sing a few lines on Jackson and Ritchie’s excruciatingly sentimental charity song We Are the World. In the shots featuring him in the video of the making of this song he is clearly squirming with embarrassment. Soon afterwards, having been cast as the headliner in the American section of the Live Aid concert, he stumbled on stage with a clearly inebriated and unrehearsed Keith Richards and Ronnie Wood and delivered a ragged performance that seemed entirely out of kilter with the schmaltzy nature of the event.

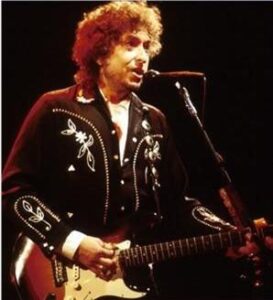

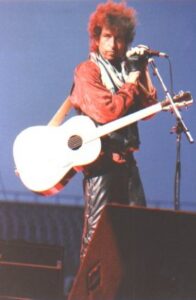

‘WE ARE THE WORLD’ ‘BIG HAIR’ BACKSTAGE AT LIVE AID BOB AND KEEF AT LIVE AID

During these years Dylan was actually extremely prolific as a songwriter, but only a handful of his songs (some of which he omitted from his album releases) could be said to replicate the combination of music and symbolist poetry which had made him so original and influential in previous decades. It might be said that in much of his music of these years, he attempted to present himself first and foremost as an entertainer rather than a poet. Despite his ‘intellectual’ status Dylan had in fact always respected the aesthetics of pop music, crediting Buddy Holly as one of his major influences. While many of the other ‘folkies’ sneered at early Beatles music, Dylan had embraced songs like I Want to Hold Your Hand with fervour. A number of his songs became pop hits in the 1960s. During his ‘rural retreat’ of the late 1960s and early ‘70s, he had composed many short country style love songs. By the late ‘70s, Dylan had developed an interest in the mainstream pop music of the day. He was particularly devastated by the death of Elvis Presley in 1977 and his ‘big band’ tour of 1978, with its ‘showbiz’ trappings, was seen by some as a tribute to Elvis’ tragic ‘Vegas period’.

Dylan’s desire to experiment with pop styles was also demonstrated by his collaboration with young backing singer Helena Springs on a series of nineteen songs which were intended to help launch her solo career and which generally eschewed lyrical complexity and featured prominent choruses. It is not known which collaborator wrote the lyrics or whether they were co-written. But the experiment cannot be said to have been a great success. None of these songs were officially released by Springs or Dylan, although some were covered by other artists. More Than Flesh and Blood, a version of which was recorded by Danish band Dissing Las and Cross, again relies heavily on repetition of the title phrase but has more developed lyrics, but contains few humorous twists such as …Time regards a pretty face like time regards a fool/ You drive off in your Cadillac and leave me with the mule… and …The meat you cook for me is blood red rare/ It’s more than flesh and blood can bear… Walk Out in the Rain, whose rather generous narrator tells his love to leave him …if it doesn’t feel right… is given an appealing if somewhat inconsequential soft-rock treatment by Eric Clapton, as is I’ll Be There By Morning, with its refrain of …I got a woman living in L.A./ I got a woman waiting for my pay…

Coming From The Heart and (I Must) Love You Too Much (the second of which was co-written with Greg Lake, vocalist with prog-rock behemoths Emerson, Lake and Palmer) were featured briefly in Dylan’s live 1978 shows. Coming From the Heart, which was played at St. Paul Minnesota on 31/10/1978 could be described as a pop-soul ballad. It boasts an appealing if hardly ground breaking chorus: … ‘Cause the road is long, it’s a long hard climb/I been on that road too long of a time/Yes the road is long, and it winds and winds/ When I think of the love that I left behind… The verses are crammed with clichés such as: …Make me up a bed of roses/ And hang them down from the vine… Later …You will always be my honey…is rhymed with …Our love can’t be bought with money….(I Must) Love You Too Much, which was played at Binghamton New York on 24/8/1978, is a sprightly pop-rock composition with much repetition of the title line. Little of Dylan’s characteristically laconic humour can be found in these songs. But the experiment, despite failing to produce any truly memorable results, appears to have provided him with a template for much of the material he would release in the 1980s. This was reflected by his experiments in covering mainstream rock numbers such as We Just Disagree (written by Jim Krueger for Dave Mason in 1977) and standards such as Fever and It’s All in the Game. In the studio, he even attempted a version of Neil Diamond’s Sweet Caroline.

A number of the more pop-oriented songs that he recorded at the album sessions appear on the Bootleg Series release Springtime in New York (2022). Don’t Ever Take Yourself Away is a Latin-flavoured ditty with very minimal conventional ‘love lyrics’ whose chorus runs: … I will never leave you/ Will never deceive you/ I’ll be right there walkin’ behind you… The object of the song is even referred to as ‘dearest’ and the narrator proclaims unconvincingly that …I can’t imagine anybody doin’/ More to me than you do… Other unreleased outtakes appear to have half-improvised lyrics. The Price of Love is centered around a Bo Diddley beat and the constant repetition of the title line. In Is it Worth It, the musicians set up a reggae-flavoured groove while Dylan throws in the odd distinctive line like …Party girl with your bluebell eyes…. Yes Sir, No Sir sets up a groove and delivers ‘dummy’ lyrics while the backing singers repeat ….Hallelujah, Hallelujah… Similarly, Borrowed Time and Magic appear to be incomplete attempts at pop songs.

Tell Me, recorded at the Infidels sessions in 1983, boasts an attractive Latinate melody and could easily have been covered by a crooner such as Tony Bennett. The title phrase is repeated constantly throughout the song, giving it a certain yearning quality. Overdubbed backing vocals by the R and B vocal group Full Force are used in a tastefully restrained way, recalling Elvis’ backing singers The Jordanaires. The song consists of a series of questions to a girl that the narrator has presumably just had a ‘brief encounter’ with. Dylan walks a tightrope here, presenting an uneasy balance between romantic tenderness and judgemental dismissal. The narrator is, it seems, ready to move on. He begins with some romantic clichés: …Does that fire still burn, does that flame still glow?/ Or has it died out or melted like the snow… which seem quite appropriate, given the musical tone of the song. The slightly tongue twisting lines such as …Is that the heat or the beat/ Of your pulse that I feel?/ If it’s not that, then what is it you’re trying to conceal… and …Do you lay in bed and stare at the stars/ Is your main friend someone who’s an old acquaintance of ours… are curiously effective despite their apparently contradictory nature, demonstrating that this is more than just a romantic paean or a lover’s put down.

Perhaps the most telling line in the song is when the narrator asks …Are those rock and roll dreams in your eyes?… suggesting that the girl is either a fully fledged groupie or someone who is merely ‘star struck’. But it seems that the narrator’s compassion is running dry …Is that a smile I see on your face… he asks …Will it lead me to glory or lead me to disgrace… He seems to be hovering on the edge of self pity here. It is thus rather hard to sympathise with him when he asks …Is this some kind of game you’re playing with my heart?…. The concluding line …Are you someone anybody prays for or cries… is actually rather cruel, inferring that her life is really empty and that she may potentially come to a tragic end. The narrator is appealing to his own inner conscience and finding only hollowness there.

Another outtake from these sessions, the tender and reflective Someone’s Got a Hold of My Heart is again based around a simple chorus, consisting mainly of repetition of the title line. In many ways it echoes the emotional reticence and confusion of Heart of Mine as Dylan attempts to come to terms with both his post-religious perspective and his position as a well known celebrity. Although it appears on the surface to be a conventional love song, Dylan’s narrator seems rather detached from his own emotions, almost as if he is watching himself from a distance. He tells us that …Everything seems a little far away to me… Anchored by a reggae inflected rhythm played by Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare, with restrained guitar work by Mark Knopfler and Mick Taylor, the song is directed at a mysterious woman who has clearly beguiled the narrator. He describes her as …a lily among thorns…an image derived from Song of Solomon 2:2, and indicating purity of spirit in a corrupt world. The narrator presents himself as a somewhat confused victim of ‘information overload’, confessing that he is struggling to come to terms with, and even to understand, his own feelings …Getting harder and harder to recognize the trap… he complains …Too much information about nothin’/Too much educated rap…

The narrator expresses considerable bemusement after having returned from an unnamed …city of red skies… a place which appears to symbolise emotional and spiritual corruption. In a slyly humorous aside he notes that …Everyone thinks with their stomach/ There’s plenty of spies… He sums up his own mental and emotional confusion by informing us that …Every street is crooked/ They wind around till they disappear….He even feels that the elements are conspiring against him, with …the moon goin’ up like wildfire.. while he feels …the breath of a storm… At this point, as if he is trying to gather up the courage to make a poetic leap, he refers to a character from Puccini’s opera, characterizing her as an enigmatic seductress who may be trying to use her wiles to ensnare him: …Madame Butterfly, she lulled me to sleep… Although he adopts the position of a conventional lover, telling the woman that she is …the one I’ve been waiting for… the one that I desire… he tempers this with another note of suspicion: …Bu t you must realize first/ I’m not another man for hire… Thus, despite being captivated by the woman, he is unsure of both her intentions and his own possible commitment to her.

In the concluding verses Dylan takes several imaginative leaps. He appears to be back in the ‘city of corruption’ in some indistinct time period. Up on the ‘bandstand’ he hears a ‘hot blooded singer’ delivering several well known standards: …Poison Love, Red Roses for a Blue Lady and Memphis in June… Poison Love is a country song first performed by Johnnie and Jack in 1952. Red Roses is a ballad from 1948 and Memphis in June is a wistful Hoagy Carmichael tune written in 1945 for the film Johnny Angel. The sentimentality of these songs is contrasted against the unexpected …While they’re beating the devil out of a guy for wearing a powder blue wig… By now we may suspect that the song does not recount a conventional love narrative. It may be that Dylan is identifying the woman with the ‘seductive’ religious sect he had briefly been a member of. Suddenly here he gives vent to his disgust at those who are ‘beating the devil’ out of an innocent man. This could be interpreted as an indication of his disillusionment with a sect which, like many Christian fundamentalist groups who supposedly profess God’s universal love but also exhibit extreme homophobia.

In the final verse the song’s relevance to Dylan’s experience of being a member of this sect is made more explicit. He now piles up the Biblical allusions, first ‘confessing’ that he has …been to Babylon… In the Bible the Jewish people are held captive in this city, the capital of the Persian Empire, and the name has become a byword for evil and corruption, especially in Rastafarian reggae songs in which ‘Babylon’ is often used to symbolise the various Western societies in which black people are often positioned at the bottom of the social order. The narrator also tells us that …I can still hear that voice crying in the wilderness… This refers to Isiah 40: 3-8 in which the ‘voice’ in the desert is crying out for God to intervene in human affairs. The fact that the narrator tells us he can ‘still hear’ that voice again suggests his spiritual disillusionment; the implication being that the religious group he has been involved in are actually part of ‘Babylon’. This is further emphasised in the mysterious and powerfully suggestive concluding lines: …Never could learn to drink that blood and call it wine/ Never could learn to look at your face and call it mine… Here, in a reversal of the Christian notion of transubstantiation (the belief that wine used sacramentally in a mass ‘becomes’ the body and blood of Christ) Dylan gives perhaps his clearest indication of his inability to fully accept Christian doctrines. Through the reversal, and the previous reference to a homophobic assault or murder, he indicates his revulsion at the way such doctrines have been perverted by religious organisations to justify prejudice and the persecution of minorities. The final line re-emphasises his disenchantment with religious dogma in the light of this revelation.

When Someone’s Got a Hold was released on the first Bootleg Series collection in 1991, many commentators expressed surprise that such a strong and heartfelt piece of work was excluded from Infidels. It is possible that Dylan was unsatisfied with the song and unsure about the sentiments he had found himself expressing within it. In 1985 it was almost completely rewritten for Empire Burlesque as Tight Connection to My Heart. With this album, Dylan made his most explicit attempt to become an ‘80s pop star. The music and arrangements are particularly inspired by the music of Dylan’s fellow Minnesotan Prince, whose inventive musical innovations made him perhaps the most influential figure in the popular music of the era. The song was even publicised by an extremely ‘cheesy’ pop video in which Dylan, as is usual in such productions, looked distinctively uncomfortable, especially when called upon to lip-synch.

Empire is Dylan’s most ‘produced’ album, including a number of overdubs (the kind of ‘studio trickery’ that Dylan had always eschewed in the past) and funk and soul influenced pop songs. In the case of Tight Connection, the basic track from Someone’s Got a Hold was used to create the new song. A ‘click track’ drum sound was added, along with prominent synthesizers. Three female backing vocalists were used to counterpoint Dylan’s new vocals. Dylan even adds two choruses. He himself sings in a more conventional way than usual. The ‘girls’ repeat the title phrase at the beginning and end of the song while the main chorus between the verses runs …Has anybody seen my love….(repeated three times) … I don’t know/ Has anybody seen my love?… The result is an attractive sounding production and the song is undeniably ‘catchy’. However, many Dylan fans felt that the production ‘gimmicks’ rather detracted from the force of the lyrics. The two recordings of the song from the Supper Club show in 1993, delivered against a basic rock backing with more obviously ‘Dylanesque’ vocals, are seen by many as better showcases for the song. Perhaps the most effective cover version is sung by Sheila Atim in the stage musical of Dylan’s songs Girl from the North Country, where it is transformed into a highly affecting and soulful ballad.

Despite their obvious musical similarities, it is perhaps useful to consider Someone’s Got a Hold and Tight Connection as separate songs. The mood of the later work shifts from introspection to optimism, with touches of humour, while the post-religious angst of the earlier song is somewhat absent. The character of the narrator also changes, making Tight Connection a more authentic love song. The persona Dylan adopts is also affected by his liberal use of dialogue from old Hollywood movies from the 1940s and ‘50s; almost all of which are lines spoken by Humphrey Bogart. By inserting these lines Dylan makes the narrator appear more laconic and ‘tough talking’, as Bogart’s characters usually were. Along with the ‘pop’ production, this has the effect of making his lines more tongue in cheek. The song begins provocatively with …Well, I had to move fast/ But I couldn’t with you around my neck… establishing the ‘tough guy’ persona. These lines are taken from Sirocco, a relatively obscure 1952 film in which Bogart pays a hard bitten war veteran and gun runner. Dylan follows this with …I said I’d send for you and I did/ What did you expect? … another half-jokey/ half-cynical riposte, still in ‘Bogart speak’ mode.

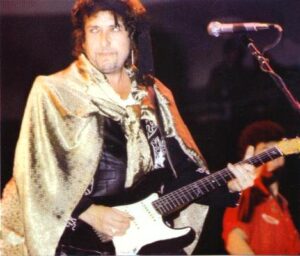

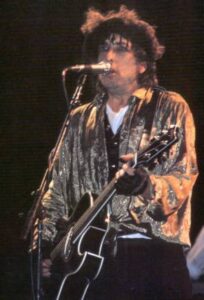

DYLAN WITH BEARD!

The second verse includes the line …I’ll go along with the charade until I can think my way out… which originates from Tokyo Joe (1949), in which Bogart plays another hard bitten war veteran. Dylan’s lines … I know it was all a big joke/ Whatever it was about/ Someday maybe I’ll remember to forget… could easily have been spoken by Bogart’s character. These early verses establish the narrator as such a character – one who has had a tough life but deals with situations by using pithily self-deprecating comments. The third verse from Something is retained, but the fourth verse again quotes Bogart. The first line …You wanna talk to me. Go ahead and talk… and the third …I must be guilty of something….are both from Oklahoma Kid, a 1939 Western in which Bogart stars with James Cagney. Dylan follows these lines with more of his own ‘film noir’ dialogue: …Whatever you gotta say to me won’t come as any shock… and …You just whisper it into my ear…

The protagonist, like many of Bogart’s characters, has to take a cynical view of life because it has dealt him a number of bad hands. Later he delivers another line from Sirocco: …I can’t figure out whether you’re too good for me/ Or I’m too good for you… It seems that the woman he is addressing has actually left him, or that their relationship is doomed. By adopting the ‘Bogart’ character the narrator can be heard to deal with this situation with characteristically laconic acceptance. Madame Butterfly also reappears from the earlier song, but she herself has been transformed into a slick-talking film noir heroine who now tells him to …Be easy baby/ There ain’t nothin’ worth stealin’ round here…. We are told that …she lulled me to sleep/ In a town without pity/ Where the waters run deep… A Town Without Pity is a 1961 film about American soldiers on trial for rape. Its title song, which focused on persecuted lovers, was a hit for Gene Pitney in the same year.

Perhaps surprisingly, the final three verses stick quite closely to those in Something. The ‘hot blooded singer’ is now only singing the one song – Memphis in June – but otherwise that verse is retained. We now hear that the ‘guy with the wig’ will later be shot …for resisting arrest… and it is now his voice that we hear …crying in the wilderness… The lines about ‘blood and wine’ are also retained. These final verses again work as a kind of impressionistic coda to the rest of the song. But despite being full of witty lyrical twists, they seem less linked to the overall narrative than they did in the previous version, although the cynicism of the ‘blood/wine’ reversal seems to suit the ‘Bogart’ character well. The song now comes over as a bitter love song. The narrator surely knows that the affair with ‘Madame Butterfly’ is over but accepts the situation with good humour.

In three songs on Empire Burlesque, Dylan plunges quite explicitly into the romantic/tragic territory of mainstream pre-rock songs. This was an area which he would later explore in his music of the 2000s. But while later songs like Love and Theft’s Moonlight and Bye and Bye subtly subvert the genre, these songs are unashamedly sentimental in tone and feature a number of rhymes which sound as corny and contrived as many of those old numbers. Dylan seemed to be quite deliberately entering an arena which was the polar opposite of his established stance as a poetic songwriter. It was hardly surprising that many of his fans were extremely bemused by this. I’ll Remember You has some similarities to a song of the same title which Elvis Presley performed on stage many times in his Las Vegas years. The recording on Empire Burlesque features restrained backing from Mike Campbell and Howie Epstein from Tom Petty’s Heartbreakers on guitar and bass. There are more ‘click track’ drums supplied by Don Heffington of Lone Justice. As with Tight Connection, synths and percussion were later overdubbed.

The song features lyrics that require little interpretation. It does, however, boast a memorable melody. Dylan was clearly fond of the song, performing it over 200 times in concert, often with considerable commitment and belief. It often functions as a contrast to or perhaps light relief from his ‘heavier’ material. It begins … I’ll remember you/ When I’ve forgotten all the rest/ You to me were true/ You to me were the best… and continuing in much the same vein. Apart from the bridge section, which runs …Didn’t I, didn’t I try to love you?/ Didn’t I, didn’t I try to care?/ Didn’t I sleep, didn’t I weep beside you/ With the rain blowing in your hair… the song could be written about a ‘dear departed’ friend as much as a lover. There are various allusions to death. The narrator tells us he will remember the object of the song …When I’m all alone/ In the great unknown… Apart from the reference to the wind ‘blowing through the Piney Woods’… there is no notable concrete imagery. The song is a kind of elegy, either to a lost lover or a dead friend. At a stretch, one might imagine it is Dylan expressing his regret at being unable to continue having faith in Jesus. Certainly his reference to the afterlife as ‘the great unknown’ indicates little religious certainty.

Emotionally Yours uses a similar line up of musicians with prominent overdubbed synthesizer, although an alternate ‘undubbed’ take which is featured on the Springtime in New York release from The Bootleg Series reveals a more upfront and committed vocal from Dylan. The song itself is a straightforward ballad which though reveling in clichés is efficiently delivered, demonstrating that Dylan is capable of mastering the form of a soul-inflected pop song which could almost be called a ‘power ballad’. Such ‘over the top’ songs like Bonnie Tyler’s Total Eclipse of the Heart (1983) or The Power of Love by Jennifer Rush (1984) were highly popular in the mid 1980s. Dylan’s song is a little more restrained and the sentiments are expressed in a sincere way. But the composition itself communicates little more than the title suggests. It is a straightforward formulaic love song in which the first two lines each of the three verses begin with invocations consisting of …Come baby… with the girl being asked to ‘find me, show me, rock me, teach me’ and the like. In the third line of each verse the narrator tells us he will be ‘learning’, ‘dreaming’ and later ‘unravelling’ which are rhymed with ‘yearning’, ‘believing’ and ‘traveling’. The singer tries to woo her by telling her …You’re the one I’m living for….The bridge, which departs from this formula, at least presents a different perspective, as the narrator appears to be desperately trying to believe his luck in finding her …It’s like my whole life never happened/ When I see you, it’s as if I never had a thought… before sliding into ..I know this dream, it might be crazy/ But it’s the only one I’ve got… It is easy to imagine ‘Vegas Elvis’ wrapping his larynx around such sentiments.

Never Gonna Be the Same Again, in which a lover expresses his regret at his treatment of the girl, is a less convincing attempt at a romantic song, containing some of Dylan’s most contrived lyrics. After telling the object of the song that she is …a living dream… he confesses that …Every time you get this close it makes me want to scream… This is, it seems, meant to be a compliment. Later we hear that …Sorry if I hurt you baby/ Sorry if I did/ Sorry if I touched the place/ Where your secrets are hid… Later he admits that …I can’t go back to what was baby/ I can’t unring the bell… a bizarre use of legal terminology in this context. To compound this …You took my reality/ And cast it to the wind… even makes a half-assured allusion to Dylan’s own classic Blowin’ in the Wind. Although the backing singers contribute enthusiastic vocals to shadow many of the lines, the track is again plagued by a metronomic drum pattern. In later live performances, Dylan recasts it as a restrained country croon, making the narrator’s inarticulacy becomes more appealing and convincing.

During the extensive studio sessions Dylan took part in for Empire Burlesque he also recorded several other ‘poppy’ compositions in different genres. The lyrics to these songs are fairly perfunctory, as Dylan plays around – sometimes uncertainly – with various musical forms. Although such material is decidedly lightweight, Dylan appears to be on surer ground than his relatively contrived attempts to be romantic or tragic in songs like Never Gonna Be the Same Again or Emotionally Yours. The cheerful and possibly unfinished Waiting to Get Beat is perhaps the nearest Dylan gets to an authentic reggae sound. He even tries somewhat unconvincingly to adopt a ‘Johnny Two Bad’ persona as he makes rather empty threats to his errant lover: …You’re playing around with daddy, baby/ When you should have quit/ Nobody messes up one of these boys/ And gets away with it….Straight A’s in Love, which is a kind of rewrite of the Johnny Cash song of the same name, is a tongue in cheek diatribe addressed to a girl whose academic achievements are minimal. There are some effective lyrical touches, as we hear that …In history, you don’t do too well/ You don’t know how to read/ You could confuse Geronimo/ With Johnny Appleseed… The song hits an appealing rockabilly groove, with some sprightly guitar work by Mike Campbell. Go ‘Way Little Boy, which was written for the LA Band Lone Justice, fronted by singer Maria McKee, is another light hearted effort, written from a female point of view. The narrator continually spurns her lover but we soon realise that she is really in love with him:…Go away little boy… she complains …You’re making me cry…

In contrast, Under Your Spell, the concluding track on 1986’s Knocked out Loaded, is a subtle and quite precisely written song which demonstrated that Dylan could produce pop-oriented material in a surer, more sophisticated manner. Here he shares the writing credits with Carole Bayer Sager, whose well known compositions include cleverly constructed and witty pop songs like A Groovy Kind of Love and It’s the Falling in Love. Perhaps the discipline of writing with such a distinguished figure had sharpened Dylan’s sensibilities somewhat as this is a fully realised composition with a haunting melody and lyrics which are carefully constructed to suggest a confused but forthright narrator who is expressing regret about his missed opportunities as a lover. Lines like … I’d like to help you but I’m in a bit of a jam/ I’ll call you tomorrow if there’s phones where I am… make the weakness of his protestations clear. He admits that she can ‘read him like a book’, while his excuse for mistreating her in the memorable phrase …I was knocked out and loaded in the naked night… seem to suggest that he was too stoned or drunk to cope with the situation, which is later confirmed when he tells her …I’ll see you later when I’m not so out of my head… Although he states that …You were too hot to handle, you were breaking every vow… his assertion that …I trusted you baby, you can trust me now… is hard to believe. The use of such unreliable narrators would be a common feature of Dylan’s ‘late period’ songs from 1997’s Time Out of Mind onwards.

CAROLE BAYER SAGER

The song has an unusual rhyming structure in that it mainly consists of three line verses, with the first two lines rhyming and the third lines rhyming with each other – so we get …under your spell…. What a story I could tell… and ….caught between heaven and hell… These ‘end rhymes’ provide a kind of commentary on the rest of the song. In the final verses the questions …Is there anything left to tell… and …Baby what more can I tell?… provide an effective lead up to the final verse, which takes us into more metaphorical territory: …The desert is hot, the mountain is cursed/ Pray that I don’t die of thirst/ Baby, two feet from the well…. The song then suddenly stops dead, leaving us to further question the authenticity of the narrator’s pronouncements.

The critical and commercial failures of much of Dylan’s 1980s music eventually led him towards a radical reconstruction of his methods of composition. Soon he was to develop new approaches to songwriting on the albums Oh Mercy (1989) and Under the Red Sky (1990). He would abandon the musical and sartorial trappings of his attempts to position himself as a mainstream pop-rock star and go ‘back to basics’ with the stripped-down rock bands of the early Never Ending Tour. In the 2000s, however, he would demonstrate his continuing fascination with the many forms of such music on his radio show Theme Time Radio Hour. Many features of his 1980s experiments with ‘pop’ styles would later feature on his post-1997 albums. But there is little doubt that many of his songs from this period represent the least authentic and committed, and perhaps most confused, phase of his career.

Leave a Reply