JOHN WESLEY HARDING: PARABLES AND LULLABIES

…The King looked anxiously at the White Rabbit, who said in a low voice, “Your Majesty must cross-examine this witness.”

“Well, if I must, I must,” the King said, with a melancholy air, and, after folding his arms and frowning at the cook till his eyes were nearly out of sight, he said in a deep voice, “What are tarts made of?”

“Pepper, mostly,” said the cook.

“Treacle,” said a sleepy voice behind her.

“Collar that Dormouse,” the Queen shrieked out. “Behead that Dormouse! Turn that Dormouse out of court! Suppress him! Pinch him! Off with his whiskers!”

For some minutes the whole court was in confusion, getting the Dormouse turned out, and, by the time they had settled down again, the cook had disappeared…

Lewis Carroll, Alice”s Adventures in Wonderland (1865)

…And if you ever saw Wes Hardin draw you know he can skin his gun

He won’t say how many tried and died

Up against the top hand, up against the wrong man, cause Hardin’ wouldn’t run…

Johnny Cash, Hardin Wouldn’t Run (1962)

The songs on John Wesley Harding are amongst Bob Dylan’s most deceptively simple and enigmatic. The backing, consisting of just bass and drums, is quiet and generally unobtrusive. Dylan’s acoustic guitar dominates, with particular emphasis on his harmonica. Each song is restricted to three verses and there are no choruses or bridges. The vocals are delivered in a soft – sometimes almost spoken – croon, while the use of language is stripped down to the bare minimum. An archaic form of discourse, which is often close to the tone and style of the King James Bible, is adopted. We are presented with a series of understated linguistic puzzles, with each song appearing to veer towards being some kind of moral homily. But the nature of the lessons that we are presumably meant to learn is highly ambiguous. It is as if listeners have been left to ‘fill in the gaps’ between the lines and to create their own imaginative interpretations of each song.

JOHN WESLEY HARDING AND THE COWBOY GENRE

The opening title tack lures us into the album’s timeless, sepia-coloured parallel world with an apparently simple story, cast in the form of a popular gunfighter ballad. The 1950s and early ‘60s were the great heyday of the Western. Countless ‘cowboy’ films and TV shows were produced, in which real historical figures such as Jesse James, Billy the Kid, Wyatt Earp, Wild Bill Hickok, Calamity Jane and Annie Oakley – many of whose lives had already been turned into ‘legends’ in pulp comics – were cast in a variety of scenarios, often with little regard for historical accuracy. As with the movies and TV shows, they generally featured ‘modern’ characters (often ‘clean cut’ and displaying suspiciously contemporary attitudes) in a historical guise. The ‘Wild West’ thus became established as a foundational American mythology. Gunfighter ballads, some of which appeared in these screen adventures, were another extension of this mythic world. Such ballads had long been a prominent feature of country or ‘hillbilly’ music. Marty Robbins’ songs such as El Paso and Streets of Laredo were like compressed Western movies, often relating their violent tales with a kind of amused detachment. Johnny Cash’s songs, such as Don’t Take Your Guns to Town, were more likely to be warnings about the consequences of idealising such violence.

MARTY ROBBINS

WOODY GUTHRIE

Dylan’s song, which opens with breezy guitar strumming and prominent bass, begins with a few apparently simple lines which we might expect to develop into a detailed account of the eponymous hero’s life story. This would normally involve stand offs in saloons, thrilling chases on horseback and climactic ‘shoot outs’. The opening lines set the tone: …John Wesley Harding was a friend to the poor/ He traveled with a gun in every hand… It seems as if this will be the story of a good hearted outlaw who, like the hero of Woody Guthrie’s Pretty Boy Floyd, became a popular hero by defying both authority and social conventions and by helping ordinary people. Yet there is already a definite strangeness to the tone of the language, especially with the use of the word ‘every’. How many hands, we might ask, did he have? The use of the word somehow suggests that he could be present in ‘every’ difficult situation – a heroic figure who would stand up for the powerless and dispossessed.

JOHN WESLEY HARDING – QUITE A GUY!

The description continues with studied vagueness: …All along this countryside he opened many a door/ But he was never known to hurt an honest man… The image of Harding ‘opening many a door’ suggests that he was a ‘true Southern gentleman’ who habitually opened doors for ladies, as was the custom in those days. After a breezy harmonica break, the second verse begins: …’Twas down in Chaynee County, a time they talk about/ With his lady by his side he took a stand… It now seems as if we will be given some juicy details of his gun fighting career. But all we get is: …And soon the situation there was all but straightened out/ For he was always known to lend a helping hand… Dylan’s delivers the lines with light irony, still sounding breezily cheerful. He is clearly taunting us now. The next harmonica break is slightly longer, before he launches into the final verse, which promises to give us some details of the outlaw’s fame and notoriety: …All across the telegraph, his name it did resound/ But no charge held against him could be proved… We are still waiting for more details, but all we get is …And there was no man around who could track of chain him down/ He was never known to make a foolish move… Drums, bass and harmonica kick in again, as our hero presumably rides off into the sunset.

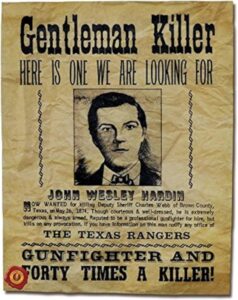

As many Dylan scholars have pointed out, the real John Wesley Hardin was nothing like this idealised character. He was a self confessed multiple killer, whose career as a gunslinger began in his early teenage years and who is estimated to have murdered at least twenty five people. He was also a racist and an opponent of the era of reconstruction which was imposed upon the South after the Civil War. Yet, like Jesse James and Billy the Kid, he did become something a folk hero in his day. He was certainly admired as well as feared. Eventually the law caught up with him and he was incarcerated. Strangely, he turned out to be a model prisoner, so much so that after fifteen years his sentence was commuted and he emerged from jail with a qualification to practice law. But he soon returned to his old ways and was eventually shot in the back of his head by a rival in cold blood.

JOHN WESLEY HARDIN

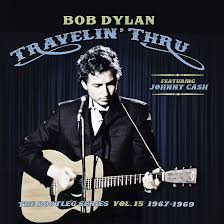

It is significant that Dylan added an extra ‘g’ to Hardin’s name. It is likely that the ‘mis-spelling’ was quite deliberate, indicating that he was presenting a partly fictionalised version of the character, much as in The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll he had changed the name of another murderer, Zantzinger, to ‘Zanzinger’. Dylan would certainly have been aware of the 1962 Johnny Cash song Hardin Wouldn’t Run which also presented the legendary gun slinger as something of a hero. It is arguable, given the lack of real biographical detail, that the song could have actually used the name of any Wild West figure. But the forenames ‘John Wesley’ also conjure up associations with the leading eighteenth century Methodist preacher of the same name. This chimes with the album’s apparently ‘puritanical’ tone. Dylan was also clearly aware that the real life Hardin was a self-mythologist who, after his release from prison, composed an autobiography in which, apart from exaggerating the number of people he had dispatched, claimed that all his killings were either done in self defence or were perpetrated against those who ‘deserved to die’. It is unlikely, however, that he swallowed such claims uncritically, despite the assertion that ‘Harding’ …was never known to hurt an honest man…

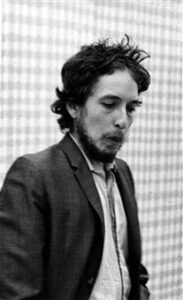

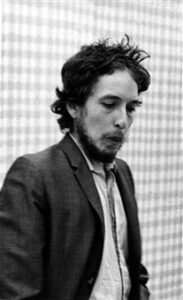

By giving us only the bare bones of the story as the title track of an album full of epigrammatic parables, Dylan announces to us that he is operating in a mythological or ‘Homeric’ realm with a particularly American slant. The black and white cover photo of the album, depicting Dylan in a rural setting accompanied by some mysterious-looking ‘backwoods characters’, appeared to be an element in his own self-conscious myth-making. The album was his first release after the madness of the 1965-66 ‘going electric’ controversy, with the existence of the Basement Tapes – recorded earlier in 1967 – still unknown to the public. Following his motor cycle accident in 1966, the wild anarchic poet of Highway 61 Revisited or Blonde on Blonde had now apparently been replaced by a short haired, sensibly dressed ‘family man’ living a quiet life in his rural retreat in upstate New York. This modest ‘retro’ image was in stark contrast to the psychedelic excesses of 1967 – the year of Sgt. Pepper and the fabled ‘summer of love’.

The song John Wesley Harding can be seen as a tongue in cheek mythological defence of Dylan himself – a ‘retired outlaw’ who suffered great vilification, performing an entire tour in which he was booed vociferously every night for changing his musical style, yet who was essentially innocent of the crime of betrayal he was being accused of. Yet he does not now sound angry, as he did when he unleashed that ‘terrifying’ version of Like a Rolling Stone at Manchester Free Trade Hall as a response to be labelled a ‘Judas’. He teases his listeners with this supposedly simplistic and apparently light hearted song, pretending to have morphed into a straightforward ‘country balladeer’. This will set the tone for the series of cryptic parables which is to follow.

The Drifter’s Escape is another short, deceptively simple piece in which we are given a mere outline of the actual story. Again, we are left to ‘fill in the blanks’ ourselves. The song tells the story of an unnamed person who is on trial for an unspecified crime. In a Kafkaesque twist, he does not even know what he has been accused of. No historical or geographical context is given. Like John Wesley Harding, he seems to be an innocent man. Drums are a little more prominent here and the verses are again punctuated by harmonica breaks, although these are shorter than on the title track. The song was revived in a full rock arrangement and was performed around 200 times on the Never Ending Tour. The title character is, it seems, another outsider from society. Dylan may be making an allusion to Hank Williams’ alter ego ‘Luke the Drifter’, renowned for his spoken word moralistic homilies. The story is again told in the third person, although an ‘I’ narrator makes a brief ‘cameo’ appearance in the first verse: …”Help me in my weakness!” I heard the drifter say/ As they carried him to the court room and were taking him away… Later our sympathy is invoked as he complains that …My trip hasn’t been a pleasant one and my time it isn’t long/ And I still do not know what it is that I’ve done wrong…… inferring that he is very old or infirm as well as an innocent victim.

We then switch to the judge, whose reaction to the Drifter’s plea is quite bizarre. We are told that he …cast his robe aside… and that …a tear came to his eye… Then he cries “You fail to understand… …Why must you even try?”… This is all the explanation he gives. Meanwhile, outside the courtroom a crowd is ‘stirring’. The judge ‘steps down’ while the jury …cries for more… It seems as if the Drifter is caught up in some kind of surreal scenario, whose logic recalls the ‘Who Stole the Tarts’ trial in Alice in Wonderland. We will never learn why he is on trial or why the judge has become so emotional. In the final verse, Dylan employs a deus ex machina device as the courtroom is suddenly struck by lightning. Then we hear that …as everybody knelt to pray, the drifter did escape…

WHO STOLE THE TARTS?

Again, the listener is required to make some sense from all this. We hear that the jury, as if it is an angry mob, ‘cries for more’, although more of what is unclear. There is a suggestion that an actual angry crowd, perhaps a lynch mob, has gathered outside the court room where it may be ‘baying for blood’. The song is so unspecific that it can be interpreted as depicting the trial of any political dissident or innocent person who has been accused on an unspecified crime, such as happened frequently in Stalin’s Soviet Union. It may be that the accused is some kind of hobo, who has been arrested merely for vagrancy. Perhaps he is a black person in the South facing an all-white jury. On the other hand, the song could also be another cipher for Dylan’s own situation. On his ’66 tour he had indeed faced an angry mob who were ’baying for blood’ at his supposed sell-out to commercialism. But now, following the ‘lightning strike’ of his motor cycle accident, he has escaped from the insane ‘trial’ of the rock and roll lifestyle.

I Am a Lonesome Hobo is another song featuring an ‘outsider’. This time, however, Dylan employs a first person narrator and gives us considerably more information. The instrumentation is again very basic, with the harmonica breaks now helping to create a bluesier feel. Like the title track, the song was never played live. Under the influence of Woody Guthrie (who at one time actually lived the life of a hobo) Dylan had previously composed Man on the Street and Only a Hobo, two songs in which innocent homeless persons were found dead on the street and were depicted as ‘victims of society’. This ‘hobo’, however, confesses to having committed many crimes. He tells us …I am a lonesome hobo with no family or friends/ Where another man’s life begins, that’s exactly where mine ends… and that he has served a number of prison sentences for …bribery, blackmail and deceit… Although he confesses to being a sinner, he is neither repentant nor unrepentant. In fact he sounds rather proud that at one time he was …rather prosperous… boasting that …there was nothing I did lack/ I had fourteen-karat gold in my mouth and silk upon my back…

The ‘hobo’s down fall is described in semi-Puritanical language …But I did not trust my brother, I carried him to blame/ Which led me to my fatal doom, to wonder off in shame… as if he is a modern version of a Biblical figure like Cain or Jacob, or even Judas. Then he leaves us with a pointedly moralistic message, addressing the listeners with studied politeness as : …Kind ladies and kind gentlemen… declaring that he will soon ‘be gone’ but warning us that we should …Stay free from petty jealousies, live by no man’s code/ And hold your judgement for yourself, lest you wind up on this road… This is the kind of tone that Luke the Drifter frequently adopts.

The ‘hobo’ presents the opposite side of the moral coin to John Wesley Harding or The Drifter. He has been punished for his transgressions, partly by the law but mostly by his own conscience. In many ways his voice might be said to be that of the real life John Wesley Hardin. The Hobo can also be seen as an alternative version of the pre-crash Dylan. He asserts that, before he changed his lifestyle, he had lost his moral compass. But despite the measured use of archaic speech and the sermon-like timbre, the song’s sentiments are quite explicitly non judgemental. The Hobo does not submit to divine judgement or moral opprobrium. He tells us to ‘live by no man’s code’ and asks for our sympathy – instructing us to imagine how we might behave if the circumstances of our lives had been like his.

The Wicked Messenger, the last of the sequence of ‘songs with a message’ on the album, is highly portentous. Like The Drifter’s Escape it became a Never Ending Tour staple with a dramatic rock arrangement, a pattern which Patti Smith followed in her electrifying live cover. In its live incarnation its apocalyptic atmosphere is especially emphasised, although in the context of the album it is presented as another simple parable. Again the minimal lyrics are highly suggestive. Like All Along the Watchtower, it gives us just the outlines of its story and its language mimics the tenor of the King James Bible.

THE PROPHET ELI

The song begins with an explicit Biblical reference:…There was a wicked messenger, from Eli he did come… In the book of Samuel, Eli is a priest who is punished by Jehovah for the sins of his sons. Eli himself is not, however, really a wicked figure. Like Dylan, he has been subjected to unjust judgement and ‘punishments’. The Messenger’s response to the question of who had sent for him is especially Dylanesque. We are told that he merely …answered with his thumb… making a silent and highly ambiguous gesture, almost as if he is mimicking Jesus’ response to a comment made by his disciple Peter in Matthew 16: 22-24: …Get thee behind me Satan….

Very little that the Messenger is reported to have done is actually in any way wicked, although, in a marvellously slick use of alliteration we are informed that he …had a tongue that multiplied the smallest matter… a line which could be seen as a self parodying comment on Dylan’s own tendency towards extreme verbosity. We also hear that …His tongue it could not speak but only flatter… Perhaps this implies that, by delivering his songs in such complex poetic ways, Dylan has really been ‘flattering’ his audience by expecting them to understand the depth and nuances of his poetry. Because his ‘messages’ were delivered through the usually inane mass medium of ‘pop music’, they were inevitably misunderstood. When he abandoned his role as an explicitly ‘political’ writer to pursue his aesthetic ideals, he was indeed treated by many as wicked – a betrayer or indeed a ‘Judas’.

JESUS AND JUDAS

In the second verse, the Messenger is portrayed as a simple, honest fellow who had broadcast his messages in the ‘Assembly Hall’, presumably a place for religious gatherings, where he had (perhaps metaphorically)‘made his bed’. …Often times… we are told… He could be seen returning… This can be seen as an ironic image of Dylan’ early role as an earnest ‘protest singer’. Then, in a memorable comic twist, we hear that… one day he just appeared with a note in his hand which read/ ‘The soles of my feet, I swear they’re burning’… The role of messenger has now, it seems, overwhelmed him and he clearly wishes to abandon his prophetic role. But there is a massive reaction against this. Biblical imagery, consisting here of a parody of Moses’ crossing of the Red Sea, is again used to describe an apocalyptic scenario: …The leaves began to fallin’ and the seas began to part…. His is drowned out by another angry mob, who had once hung onto his every word, but who now reject him, telling him…if ye cannot bring good news then don’t bring any…

In his ground breaking Song and Dance Man (1973), the first comprehensive critical study of Dylan’s work to be published, Michael Gray persuasively argues that these words presage the lack of ‘messages’, not only on the album’s last two tracks but on Dylan’s subsequent albums Nashville Skyline, Self Portrait and New Morning. If understood in this way, this is especially ironic, as the instruction not to deliver ‘messages’ is in itself a ‘message’. But there is certainly a sense throughout John Wesley Harding that many of the characters in the album’s cryptic songs – the outlaw, the drifter, the hobo, the joker, the gambler and the messenger – resemble the performer who was vilified for changing his style and approach to his art. While in Lonesome Hobo he exhorts his listeners not to be judgemental, here the messenger is confronted by a highly condemnatory mob who demand he give them only ‘good news’.

The use of this phrase is another sly Biblical reference. The word ‘gospel’ means ‘good news’ – but the mob, who certainly do not ‘hold their judgements to themselves’, are clearly only interested in the kind of ‘good news’ that they have already come to expect. Here Dylan appears to be casting a withering look at those who barracked him for adopting his new style and lyrical stance, suggesting that they resemble a group of mindless religious fanatics who do not accept any alternative views apart from their own. The use of ‘ye’ here rather than ‘you’, in a quite deliberate use of ‘King James Bible’ English, emphasises this.

Dylan’s extensive appropriation of the style of the classic translation of the Bible on the album has been retrospectively interpreted by some commentators who argue that he had always been a conventionally religious artist, even years before his ‘born again’ phase. But despite its appropriation of a Biblical tone, John Wesley Harding avoids any kind of proselytising. The King James Bible – whatever its morality or dubious efficacy as a ‘guide to living’ – is an immensely influential work of literature whose highly rhythmic and distinctive prose has influenced generations of writers in a way that is only comparable to the works of Shakespeare. Having been vilified onstage as a Judas – a betrayer – Dylan turns this kind of language back on his detractors, asking them to question their own moral worth and integrity.

As I Went Out One Morning, which Dylan performed only once, on the 1974 tour, is perhaps the most cryptic ‘parable’ of all, despite the fact that in this song he avoids Biblical phraseology and expression. Its action again appears to take place in a mysteriously timeless zone. In many ways it mimics the mysterious tone of traditional folk songs such as House Carpenter, Nottamun Town, Belle Isle or The Lowlands of Holland, which take the listener outside of historical chronology and deliver highly ambiguous descriptions of events that take place in a symbolic ‘fever dream’. Dylan performs the piece with a certain amused detachment, never sounding especially emotionally involved in the action.

The song begins with the title phrase, which sounds like the opening line of many traditional ballads. In As I Went Out One May Morning (a folk song which was recorded by Ewan MacColl, perhaps the most dogmatic ‘folk purist’ of all) the protagonist encounters a beautiful young girl with ‘pretty little feet’ who is going out to ‘feed her father’s flocks’. The narrator immediately falls in love with her and determines to marry her. In Dylan’s song, which can be seen as a surreal parody of such ballads, the narrator also encounters a gorgeous and enticing young lady. But – rather surprisingly – she is described here, in markedly archaic language as …the fairest damsel that ever did walk in chains… It has already been indicated that the song is peopled by symbolic characters. The narrator has informed us that he has gone out …to breathe the air around Tom Paine’s… Thomas Paine (1737-1809) was a revolutionary English political activist, opposed to slavery, monarchism, conventional religion and the suppression of Native Americans. His books and pamphlets (particularly Common Sense (1776) and The Rights of Man (1971)) and speeches were highly influential on both the French and American revolutions. One would expect Paine to be represented as a symbol of progressive and liberationist thought. But, given the association with such a figure, why is she ‘in chains’?

TOM PAINE

On meeting the ‘fair damsel’ the narrator follows the conventional pattern of traditional songs. He falls in love with her at first sight and immediately offers his hand in marriage. But the narrative then takes a very strange turn. He tell us that …she took me by the arm/ I knew that very instant she meant to do me harm… He responds with …Depart from me this moment… /I told her with my voice… Dylan is known for his characteristic use of ‘double negatives’ and even ‘double positives’, which often add an extra layer of ambiguity to his songs. But this is one of his strangest uses of an apparently redundant phrase. It gives the impression of some kind of separation between the narrator and his own actions as if the ‘voice’ is somehow an independent identity.

The next exchange is fairly predictable. …Said she “But I don’t wish to”/ Said I “But you have no choice”… She will not, however, be distracted from her aims …”I beg you sir!”, she pleaded from the corners of her mouth/ I will secretly accept you and together we’ll fly South… The expression ‘corners of her mouth’ is very odd. In the earlier studio demo of the song (which appears on the Bootleg Series release Travelin’ Thru), he sings …center of her mouth… If Dylan had sung the singular ‘corner of her mouth’ we might take this as an indication that she was lying. We will, however, find no obvious solutions to these strange details. In the final verse Tom Paine himself appears. He admonishes the girl, telling her to let go of him. After she releases him Paine apologises profusely: …”I’m sorry sir”, he said to me/ I’m sorry for what she’s done… Then the song ends abruptly.

It seems very strange that Paine, who represents liberty and progressive thought, should keep a girl in chains, as if he is a slave holder which (unlike other Revolutionary leaders George Washington and Thomas Jefferson) he decidedly was not. So we may assume that, in this dream-like narrative, the girl is also a purely symbolic figure. Perhaps she can be associated with the woman in Ecclesiastes 7:26 …whose heart is snares and nets, and her hands as bands: whoso pleaseth God shall escape from her; but the sinner shall be taken by her… The story of the song is so opaque that one can see the woman as embodying many elements, such as a dangerously addictive drug or the illusions of fame and fortune, both of which the pre-crash Dylan may have been attracted to. She certainly appears to represent some form of temptation. After her attempt to ensnare him it takes the ultimate defender of liberty …Tom Paine himself… to free him. The narrator makes no comment about this, merely relating the story in his characteristically deadpan way. As with the title track, it may be that Dylan is taunting his audience by challenging and reversing their assumptions.

The album ends on a highly unexpected note, with two simple love songs. With the addition of Pete Drake on steel guitar, both anticipate the controversial ‘country’ albums that will follow. Like the other songs on the album, their musical and lyrical structures are so simple that they can easily be adapted to other musical styles. Down Along the Cove utilises an appealing soft shuffle beat and features an attractive instrumental conclusion in which harmonica and steel guitar interact. The lyrics are quite deliberately minimalistic, so much so that they can be seen as a parody of conventional love songs. The narrator twice sees his ‘true love’ coming his way. The second time he calls her …my little bundle of joy… The narrator and his lover both cry …Lord have mercy!… in celebration of their love and finally they walk off ‘hand in hand’. The song ends with …Everybody watching us go by knows we’re in love and, yes, they understand… a neat and satisfying bit of vocal gymnastics. To the surprise of many audiences this rather inconsequential number was revived as a blues, with a number of extra verses, incorporating standard blues clichés like …I got my suitcase in my hand… and …You can lay your money down… The location of the song was shifted to a …Jackson River Queen… a Mississippi river boat and haunt of gamblers. This version was played around 80 times between 1999 and 2006.

The closing track, I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight, though equally minimal in its lyricism, is one of Dylan’s most accomplished ‘simple songs’, consisting merely of three three-line verses and a bridge section. It is presented here as a ‘pure country’ number but on the hundreds of occasions he has performed it live it has morphed into many different forms, often with a bluesy inflection. The harmonica, which sounded so menacing on the earlier tracks, now seems warmly inviting, as Dylan duets with Pete Drake’s steel guitar on the intro and the outro.

The song became a staple of the post-pandemic Rough and Rowdy Ways tour, acting as ‘light relief’ between the longer, more intense songs. Cover versions abound, including ‘alt-country’ renditions by Emmylou Harris, Hank Williams Jr., Kris Kristofferson, Rita Coolidge and others. It has also been delivered as a ‘torch song’ by female soloists like Marianne Faithfull and Norah Jones. For many Dylan fans, I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight was something of a shock. Had Dylan gone soft? Had ‘the voice of his generation’ degenerated into a romantic crooner? Such cries would grow even louder when he released Nashville Skyline and Self Portrait. The song is a joyful celebration of ‘no strings attached’ sex, as the narrator implores the girl to sleep with him in a rather quirkily humorous way. This is slightly reminiscent of If You Gotta Go, Go Now, in that the faux-naïve ‘seduction technique’ is so obviously contrived. Similarly, there are no professions of love, just an invitation to have fun. The tone is gently reassuring: …Close your eyes, close the door… he tells her, clearly with a glint in his eye …You don’t have to worry any more/ I’ll be your baby tonight… The second verse is almost identically reassuring, except for a small alliterative tweak: …Shut the light, shut the shade/ You don’t have to be afraid….

In the bridge section, which is actually longer than the verses, the narrator really turns on the boyish charm, beginning with …Now, that mockingbird’s gonna sail away/ We’re gonna forget it… This is a very clever line, as it depicts a bird – which in so many songs symbolises romance – as ‘sailing away’. In other words, the narrator has no real romantic intentions and so is deliberately ‘mocking’ romantic clichés. The statement is also, of course, comically absurd. A mocking bird should of course ‘fly’ rather than sail. It is then followed by the outrageously silly ‘nursery rhyme’ of…That big fat moon’s gonna shine like a spoon/ We’re gonna let it, you won’t regret it… This slides nicely into the final verse, in which the narrator turns up the intimacy, imploring the girl to …Kick your shoes off, do not fear/ Bring that bottle over here…

Both of the closing songs, with their comical use of ‘childish’ language, are, in a sense, lullabies. The phrase …little bundle of joy… which is used in Down Along the Cove, is a common way of referring to a baby. I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight is a comical riff on the well worn cliché in popular songs (derived mainly from the blues) to address a lover as ‘baby’ or ‘babe’. The reference to a ‘mocking bird’ seems to be an allusion to the popular and catchy ‘finger snapping’ lullaby Mocking Bird, first recorded by Inez and Charlie Fox in 1963. Dylan even joked to one interviewer that the song could actually be seen as being written from the point of view of a baby. Thus, having taunted his audience with a series of inscrutable ‘parables’, Dylan concludes the album by treating us to two ‘harmless’ parodies of sentimental songs, as if rocking us to sleep. John Wesley Harding remains a uniquely beguiling entry in Dylan’s catalogue, demonstrating to his listeners that he is capable of composing material that diverges greatly from their expectations. Despite its apparently po-faced moralist, it is also one of Dylan’s most accomplished comic works, a series of oblique commentaries on the life and work of an artist who tells us – with his tongue very firmly in his cheek – that he was ‘never known to make a foolish move’.

Leave a Reply