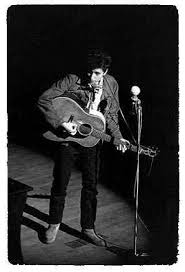

1963 was the year Bob Dylan ‘made it’. At the beginning of the year he was still a little-known folk singer with one album to his name – a rather startling collection of blues and folk covers with a couple of derivative originals – which had sold very poorly. By the end of the year he had become virtually a ‘household name’, partly as a result of the success of his second album The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan and the adoption of a number of his songs by marchers in the Civil Rights movement. The most well known, Blowin’ in the Wind, became a global hit in a rather ‘sweetened’ version by Peter, Paul and Mary. For most of the year Dylan was still playing in Greenwich Village folk clubs such as Gerde’s Folk City and the Gaslight Cafe, as well as taking part in shows featuring a number of folk singers, often at East Coast Universities, which became popularly known as ‘hootenannies’. He was still only playing a handful of full concerts. Two of these have survived in high quality recordings. Most of the material has been released on the (very) limited edition 50th Anniversary ‘copyright extension’ compilations. It is perhaps surprising that, given their historical significance, the shows have not yet featured as part of The Bootleg Series. These solo acoustic performances demonstrate quite clearly that in his live shows Dylan was capable of producing performances that equalled or outshone his recordings. They also feature his talents as a ‘raconteur’, who often introduces his songs with humorous or portentous asides, so developing a kind of intimate rapport with an audience who share both his political viewpoints and his anti-establishment sense of humour. He is part poet, part stand up comedian and part political commentator. When he ‘went electric’ some two years later, the dismay felt by some of his audience was as much to do with the loss of this direct contact with his fans as the loud noise he was making with his band.

1963 was the year of the ‘Folk Boom’ in the USA, when a mainstream singer like Trini Lopez could have a sizeable hit with If I Had A Hammer, a catchy, rousing, if rather generalised global plea for ‘freedom and justice’ originally performed by Pete Seeger’s group The Weavers. The big record companies had begun to realise the commercial potential of such material. There is little doubt that the political context of the times influenced this new vogue. The Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 had thrown the shadow of the Cold War into sharp and terrifying relief, which the rabid and fanatical anti-communism of much of the American establishment further underlined. Meanwhile the struggle against the institutional racism of American society was resulting in a number of large protests, which sometimes led to violent reactions from the authorities. The key to Dylan’s early success lay in the way he eloquently voiced the concerns of American youth about such issues. Yet unlike the ‘commercial folk’ of singers like Lopez, the Kingston Trio and Peter, Paul and Mary, who encouraged audiences to ‘sing along’ with their pleasantly presented anthems, Dylan achieved his fame with a harsh and uncompromising vocal style which was an amalgam of influences from outside the popular music mainstream, including many blues and ‘hillbilly’ singers. He was also influenced by the drily monotonal vocal style and the political subject matter of the songs of his hero Woody Guthrie.

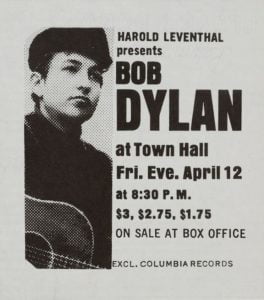

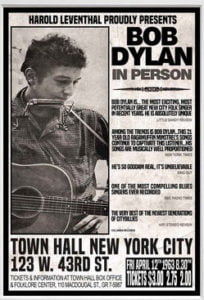

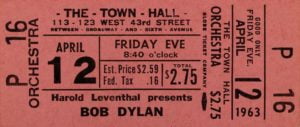

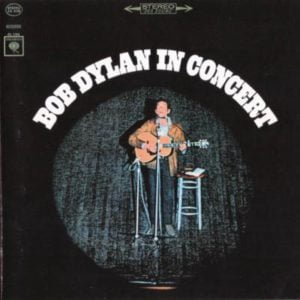

It was clear that by April 12th, when he performs his first major concert at New York Town Hall, that Dylan had begun to accumulate a considerable reputation among the cognoscenti who were already aware of him as a songwriter and who shared his radical beliefs. The Town Hall had a history of staging challenging performances. In 1921 Margaret Sanger, an early advocate of birth control, was actually arrested on its stage when delivering a lecture. The Hall had also developed a reputation as an Arts venue, staging a number of high profile poetry readings, from Edna St. Vincent Millay in the late 1920s through to the Beat Poets in the 1950s. It was also a venue which showcased the work of bebop jazz artists like Dizzy Gillespie and Lester Young, who the Beats especially admired. Even so, it is still remarkable that the comparatively ‘unknown’ Dylan still managed to attract an audience of around 900. In many ways the concert is experienced by its audience as a ‘poetry reading’ as much as a ‘musical’ performance. The concert programme even features a new ‘autobiographical’ Dylan poem My Life in a Stolen Moment and the show ended with Dylan reciting his poem Last Thoughts on Woody Guthrie.

The concert marks a significant milestone in Dylan’s career. He shows himself to be fully capable of taking his act out of the folk clubs and into a much larger public arena. He demonstrates that as a songwriter he can switch between a number of modes with ease. In order to convey the meanings and emotions of the songs, armed only with his voice, his acoustic guitar and his harmonica, he proves himself to be a very accomplished actor, slipping as he does between these different personas while never losing the attention of the enraptured audience who are, for the most part, hearing these monumental songs for the first time. In particular, the ‘protest’ songs certainly do articulate the feelings of his young audience with great eloquence. Despite all of his later denials, this is the Dylan who would soon be acclaimed as ‘the voice of his generation’.

Most of the songs he performs are completely new to the audience, so the acoustic setting is a perfect way of transmitting his poetic lyrics, every one of which could be discerned quite clearly by the audience. Very few members of his audience would have experienced such a performance before. However, with his schooling in the blues and other forms of non-mainstream folk music, Dylan no doubt saw himself more as the inheritor of a tradition of poetic song. Yet it was clear that from here onwards that he was applying a new and more explicitly literary approach to his material. The songs already display the influence of the Romantic and Beat poets, among other literary sources. At the time Dylan had only recently discovered his voice as a songwriter, but new songs were pouring out of him at a considerable rate. Some of the songs were already familiar to audiences through live versions sung by other singers. Only four of the selections were to appear on the as yet unreleased Freewheelin’ album.

When Dylan arrived in New York he set about a process of ‘inventing’ himself as a public figure. Heavily influenced by his hero Woody Guthrie’s partly fictionalised autobiography Bound for Glory, he indulged in deliberate self-mythologising, depicting himself as a Guthriesque ‘travelling hobo’. He gave a number of interviews in which he claimed to have left home at an early age, ‘rambled’ around the country, worked in circuses, ridden box cars and learned songs from chance meetings with blues singers such as Big Joe Williams. All this always seemed a little unbelievable as Dylan was barely twenty years old at the time and looked considerably younger. My Life in a Stolen Moment begins with some evocative descriptions his childhood in Hibbing:

…Hibbing’s got the biggest open pit ore mine in the world

Hibbing’s got schools, churches, grocery stores an’ a jail

It’s got high school football games an’ a movie house

Hibbing’s got souped-up cars runnin’ full blast on a Friday night

Hibbing’s got corner bars with polka bands

You can stand at one end of Hibbing’s main drag

an’ see clear past the city limits on the other end…

After this, Dylan becomes more inventive, stating that he had run away from home on numerous occasions. He claims he was thrown out an English Literature class at College for writing a poem about his teacher containing four letter words. Later we find him in California, New Mexico, Texas, New Orleans and other ‘exotic’ locations which – like Kerouac in On the Road – he claims to have hitch hiked to. The narrative becomes even more fantastical when he tells us he has been …jailed for suspicion of armed robbery… and …held up for four hours on a murder rap… The poem is somewhat prosaic at times but ends quite effectively with Dylan (in the kind of language that Guthrie might have used) outlining where his influences come from:

…What about the records you hear but one time

What about the coyote’s call an’ the bulldog’s bark

What about the tomcat’s meow an’ milk cow’s moo

An’ the train whistle’s moan

Open up yer eyes an’ ears an’ yer influenced

an’ there’s nothing you can do about it….

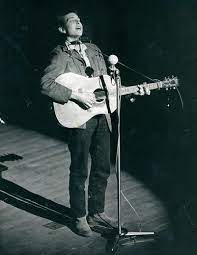

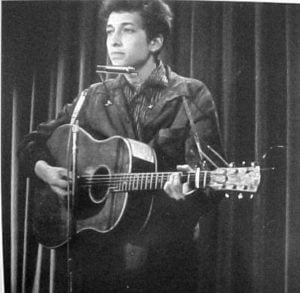

Dylan underlines his creation of this persona by beginning the show with a song he had only played once before (at Gerde’s Folk City in the previous year) and which he never performed again – a short but sprightly ditty entitled Ramblin’ Down Through the World, which consists of one verse in which the singer declares himself to be …one of them ramblin’ boys… followed by a very lively and inventive harmonica solo. Here is Dylan in his Huck Finn cap, jeans and work shirt, still identifying himself as the ‘son of Woody Guthrie’, posing as a kind of Beatnik hobo who has just blown into town. He then switches tack with a thoughtful and moving version of Bob Dylan’s Dream, which combines the use of the beautiful traditional tune Lord Franklin (about another ‘lost rambler’) its presents a rich evocation of memory and nostalgia. The narrator and his friends are on a ‘train goin’ West’, rather than riding a boxcar. Although the song evokes a life of experience which Dylan had never really led, the emotional content is completely convincing.

The third song is Talkin’ New York, a lightly ironic talkin’ blues which recounts Dylan’s arrival in Greenwich Village. Dylan changes some of the lyrics from the recorded version, demonstrating that he is already unafraid to adapt his songs onstage. This was another feature of his performances he had taken from Guthrie. After establishing this ‘ramblin’ boy’ persona he later includes Dusty Old Fairgrounds, presented here in its only live performance. The song is fairly lengthy. Each of its fourteen verses ends with the refrain …following them dusty old fairgrounds a-calling… It maintains a lively pace and a breezily optimistic tone throughout. Here he extends the fictions of Stolen Moment, producing a travelogue full of colourful descriptions and inventive rhyming whose narrator thoroughly inhabits the role of a travelling circus hand who is in love with the ‘call of the fairgrounds’, as he travels through many different towns and states. As with Bob Dylan’s Dream we are invited to believe that the song is communicating the real life experiences of the singer. This was a charade he would not be able to keep up for very long once he became truly famous and reporters began digging into his real background. But throughout his career he would continue to present his songs from behind a series of such ‘masks’: the angry ‘politico’, the philosophical ‘lover’, the surrealist, symbolist poet, the ‘family man’, the tortured lover, the Born Again prophet, the ‘burned out rock star’ and the ‘travelling minstrel’. As he demonstrates most effectively in this concert, the entire ‘Bob Dylan’ identity is a kind of dramatic construct.

In the New York Town Hall show Dylan demonstrates his ability to assume a range of different personas. Later in the set he will perform two more songs from his debut album – the traditional ballad Pretty Peggy – O (another vehicle for his virtuoso harmonica playing) and a highly impassioned take of Curtis Jones’ Highway 51 Blues which is far more powerful than the studio recording, with Dylan bending and extending his vocal lines like a true blues man and punctuating them with authentic Sonny Terry-style blues harmonica. He shows that his repertoire includes both the whoops and hollers of ‘mountain music’ and the growling tones of the blues, just as if he has really learned these songs from the mountain men of the Appalachians or the grizzled veterans of the Mississippi Delta.

Dylan adopts a different persona, that of the reticent lover, when he presents us with debut performances of two of his greatest (and most straightforward) love songs, Boots of Spanish Leather and Tomorrow is a Long Time. Before Boots he adopts a shy, humble tone as he tells the audience …I used to be quite romantic… But there is no doubt that he is still highly romantic, as he delivers a pitch perfect version of this highly evocative song of desperate yearning. Tomorrow is delivered in a similarly reverential tone. For some unknown reason this staggeringly beautiful lament never made it onto a Dylan album. The Town Hall version was later included on the More Greatest Hits compilation in 1971. Before he sings the far more equivocal Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right, he sounds even shyer and more reticent, declaring that …You gotta be pretty good to sing this song… I don’t know if I can sing it really. But I wrote it, so… This is, of course, a rhetorical trick. He delivers an impassioned version of this great country ballad.

At other times Dylan assumes a comic or satirical narrative approach. In the crudely confessional and highly suggestive ode to the pointlessness of empty intellectual philosophising If I Could Do It All Over Again (I’d Do It All Over You) and the lament of a sexually exhausted ‘poor boy’ in Bob Dylan’s New Orleans Rag he adopts the voice of a lascivious drunkard, a trick he would later pull off on several songs from The Basement Tapes. The audience responds enthusiastically to these lighter moments. He also applies his comic gifts to John Birch Society Blues, a rather heavy handed but sharply funny satire on anti-communist paranoia and Hero Blues, which he describes as being …for all the boys that know girls that want them to go out and get themselves killed… The way Dylan delivers the payoff line from this song …You need a different kind of man, babe, one that can hold your heart/ You need a different kind of man, babe, you need Napoleon Bonaparte… demonstrates his exquisite comic timing.

Although Dylan projects himself as beatnik, hobo, lover and jester, the heart of the performance lies in the more ‘serious’ songs in which he confronts contemporary social and political ills with such eloquence. Several of these songs are purely fictional. John Brown is another song that looks at how women can encourage men to go to war. Dylan adopts a third person narrative to deliver the coup de grace of this stark narrative. When the maimed soldier returns from the conflict to meet his horrified mother he merely …drops his medals down into her hand… Dylan’s performance is a dramatic tour de force of compelling storytelling. The bleak Ballad of Hollis Brown, in which a desperate farmer kills himself and his entire family, is delivered in a deathly deadpan. In Seven Curses he relates a historic tale of how a young girl agrees to sleep with a hanging judge on the premise that this will save her father, who has been condemned for stealing a horse. The father is hanged anyway and in the final verse Dylan castigates the judge in no uncertain terms.

In all of these songs, the narratives are constructed in order to rouse an audience into anger at injustice. In his didactic expose of the dangers of boxing Who Killed Davy Moore, Dylan sings about the recent death of a real person, the boxer Davy Moore, who died after receiving head injuries in the ring. The story is delivered here with heavy ironic emphasis, with Dylan virtually speaking the words. The song, which is based on the nursery rhyme Who Killed Cock Robin? has a very minimal tune. The boxer’s opponent, his manager, the sports reporter and the crowd all deny responsibility for Moore’s death. Before the rendition Dylan’s mumbled comments appear to support what he calls …the abolishment of boxing… Ironically, in later life he would become a boxing aficionado, associating with leading boxers, doing sparring practice to keep himself fit and even buying his own gym; not to mention eulogising wrongly imprisoned boxer ‘Hurricane’ Carter. Davy Moore is the kind of song which works extremely well in this kind of context, with an attentive audience following the story carefully. They are never given a definitive answer to the question that the song asks, but we cannot fail to infer that all the respondents were responsible.

Dylan also performs several ‘protest’ songs which have yet to appear on his albums. Despite this, when he begins playing A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall there is a cheer of recognition from the crowd, who have presumably heard the song performed in folk clubs, perhaps by Dylan or possibly by other artists. The more recently composed Blowin’ in the Wind and With God on Our Side do not elicit a similar response. Before Masters of War, the final song prior to the encore, Dylan delivers an ambiguous, quasi-religious introduction which is perhaps suitable for a song in which he castigates war profiteers not only by wishing that they will die but also by apparently condemning their souls : … I believe in the ten commandments… The first one is I am the Lord thy God. It’s a great commandment if it’s not said by the wrong people…. He also gives a one off rendition of You’ve Been Hiding Too Long, a very angry attack on white racists rather lacking in his usual poetic subtlety, concluding in the very unambiguous …You’ve been hiding too long behind the American flag…

For his encore, Dylan carried out the audacious and unique act of reading his poem Last Thoughts on Woody Guthrie. This epic effort – arguably Dylan’s most successful attempt at an extended poem – will be covered in a future blog in more detail. In it he eulogises his great mentor and hero, identifying him with all that is real and authentic in American culture. Dylan had been visiting Guthrie, now debilitated by the genetic wasting disease Huntingdon’s Chorea, in hospital, since his arrival in New York. The poem comes to a glorious climax with Dylan rhetorically asking the audience where they may find hope for the future, and concluding that:

…You can either go to the church of your choice

Or you can go to Brooklyn State Hospital

You’ll find God in the church of your choice

You’ll find Woody Guthrie in Brooklyn State Hospital

And though it’s only my opinion

I may be right or wrong

You’ll find them both

In the Grand Canyon

At sundown…

Dylan will never perform this remarkable work again. Although he appears to begin and end the show by embracing his ‘Guthrie persona’ he already seems to sense that it is time for him to move on. Many of the songs he has now composed are influenced by Guthrie’s sensibilities. They attack hypocrisy, exploitation and miscarriages of justice and point a finger accusingly at war mongers and racists in a way that would make Guthrie proud. But Dylan appears to sense that he has already superseded his role model and now he presents what are truly his ‘last thoughts’ on the great man with tremendous passion and intensity.

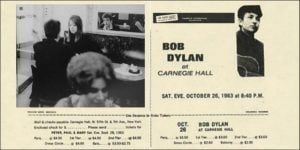

In the six months between Dylan’s appearance at the Town Hall and his concert at the larger and more prestigious Carnegie Hall, Dylan’s public profile – like that of the early American astronauts who were making so many headlines at the time – ascends into the stratosphere. There was no doubt he had ‘the Right Stuff’. In early May he made headlines by refusing to appear on the Ed Sullivan Show, American TV’s biggest ‘variety’ outlet, when he was refused permission to sing Talkin’ John Birch Society Blues. Such a move might have killed other artists’ careers but his stance only increased his public profile as an anti-establishment rebel, at a time when few performers felt capable of challenging such bastions of mass entertainment. Later that month, the Freewheelin’ album is released. Dylan formed a professional and personal relationship with Joan Baez, duetting with her on With God on Our Side at the Monterey Folk Festival and appearing regularly as a guest at her concerts. He also showed his willingness to contribute to the Civil Rights struggle by appearing at a voter registration rally in the heart of the redneck Deep South in Greenwood, Mississippi. In July his appearance at the Newport Folk Festival, again including duets with Baez, culminates in a mass ‘sing-a-long’ rendition of Blowin’ in the Wind, which by now had become a worldwide hit for Peter, Paul and Mary. He made several TV and radio appearances, as well as recording the songs for his third album, The Times They Are a-Changin’. At the end of August he sings Only a Pawn in Their Game and When the Ship Comes in (with Baez) at the Washington Civil Rights March in front of some 250, 000 people. Peter, Paul and Mary performed Blowin’ in the Wind, now adopted as the movement’s anthem. Soon after this, as Martin Luther King delivers his epochal I Have a Dream speech a mesmerised Dylan stands just a few feet away. Already, he is part of American history.

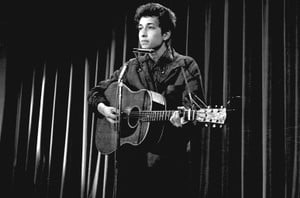

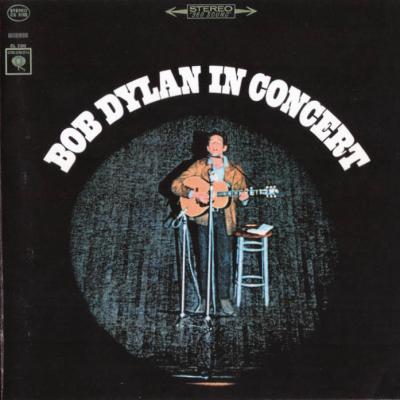

By October 26th, when he appears at Carnegie Hall, Dylan’s public profile had made him – along with Baez – the most well known face in American folk music. Already he was a ’pop star’ who had begun to attract hordes of screaming teenage girls. After the show, his friends had to carefully engineer his ‘escape’ from the venue. A few days before the show, a rather sensational Newsweek article had been published, exposing Dylan’s ‘stories’ about his supposedly ‘rambling youth’. But this has no effect on his performance, which is a triumphant vindication of his new status. The Guthrie persona is now firmly in the past. He already looks more mature and is even more smartly dressed. Every selection is delivered with precision and great clarity and is greeted by exultant responses from the crowd, despite the fact that many of the songs were being played live to an audience that had never heard them before. Only seven of the nineteen songs had featured in the Town Hall show. Eight were from the yet unreleased third album, along with three songs that were written for that album but never made the cut.

The Carnegie Hall is a highly prestigious venue, chiefly dedicated to classical music, holding over 3,000 seats. But Dylan is not phased. He begins with an exultant Times They Are a-Changin’, the ‘signature song’ with which he would open his shows until mid 1965. The performance of Who Killed Davy Moore is executed with far greater confidence than at the earlier show, with Dylan thoroughly inhabiting the voices of the song’s characters. During Boots of Spanish Leather one can hear the proverbial pin drop as he pours his emotions into the song. Before John Birch he declares …There ain’t nothin’ wrong with this song… This draws a huge cheer from the crowd, who were clearly familiar with the story of the Sullivan ‘controversy’. Perhaps the biggest surprise of the evening, however, is Lay Down Your Weary Tune; a beautiful ode to the natural world and a precursor to ‘visionary’ songs like Mr. Tambourine Man and Chimes of Freedom. Although the ‘political’ songs are still being given pride of place, Dylan is already evolving at great speed and here we get a glimpse of what he will go on to achieve in his next phase. It says much for the torrent of songs that Dylan was delivering in this period that this wonderfully poetic creation – like many of the other songs performed at these two shows – never actually made it onto a Dylan album.

Before Dylan sings the now famous Blowin’ in the Wind he entertains the crowd with some dry humour, telling them a story about an English professor who – having misheard the words – claimed not to understand the song. The performance itself is stately and triumphant, in great contrast to the more tentative reading on Freewheelin’. …How many times must a man look up… Dylan cries …Before he can REALLY see the sky… This is followed by a succession of ‘protest songs’, beginning with an extended eight minute version of the unreleased Percy’s Song, in which Dylan relates a tale of a man imprisoned for 99 years for driving a car which was involved in a tragic accident. This is followed by Seven Curses and The Walls of Red Wing, a song attacking the brutality of a reform school which had been recorded for, but not included on, Freewheelin’. In the next song, the starkly dramatic expose of ruthless capitalism North Country Blues Dylan delves into his real (rather than his invented) background, relating a riveting tale of the decline of a mining town on the Iron Range near Hibbing, Minnesota, where he had grown up. This is followed by a riveting Hard Rain, the last song before the intermission.

The second half of the show begins with a lively Talkin’ World 111 Blues, Dylan’s most effective use of the ‘talkin’ blues’ format. Already he adapts the words from the recorded version. The singer he hears in the song is no longer the fictional ‘Rock-a-day Johnny’ but the contemporary pop star Fabian, who sings …You love me and I love you/ Our love’s a gonna grow/ Shoobie doo, shoobie doo… Such improvised lyrical variations were to become an important element in his future live performances, sealing the special bond between performer and audience. The rendition of Don’t Think Twice, which follows, is more bluesy and nuanced than the Town Hall performance. Dylan alternates between loudly proclaimed and modestly understated lines, giving the song considerable dramatic tension.

For the next six minutes Dylan turns raconteur, relating a long story to the audience about going to see a movie, the recently released Hootenanny Hoot, a blatant attempt by Hollywood to cash in on the ‘folk boom’. He demolishes the movie in a number of comic asides. …I’d like to tell you about it… he says …I don’t want any of you to go see it… He then delivers a quick resume of the movie’s ludicrous plot, explaining how a ‘big Hollywood producer’ insists to his backers that making a TV show of a hootenanny he discovers by accident in the mid-West will ‘sell soap’. He also mocks the fact that the female singers performing in ‘swimming suits’ to the accompaniment of drums that …come out of nowhere… But then he insists that he and likeminded performers are decidedly not ‘selling soap’. He refers to the real Hootenanny TV show, which showcased commercialised folk music, and which had just begun its run on the mainstream ABC TV channel, but which refused to feature Pete Seeger due to its ‘ant-communist blacklist’. Dylan, Baez, Tom Paxton and many other folk singers refused to appear on the show in protest. Here Dylan expounds on the subject of such entertainment blacklists, employing the rhetorical trick of being supposedly puzzled by why such blacklists could come into place. He says that blacklisting …is a bad thing. I don’t know why it’s a bad thing but it’s just bad all around… These pronouncements produce a hearty response from the audience.

Having generated great political solidarity from the audience, Dylan completes the show by delivering inspired versions of five ‘protest’ songs, With God on Our Side, Only a Pawn in their Game, Masters of War, The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll and When the Ship Comes in. His spoken introductions, often delivered in a faux-naive tone, provide the audience with considerable food for thought. Before Masters, as he strums the ominous opening chords, he answers his critics by stating …some people say this song is very ‘naive’ … (putting considerable ironic emphasis on the last word) What follows is quite extraordinarily unequivocal: …Well I got to stand here and really not care because I do actually hope that the masters of war die tomorrow… Hattie Carroll is …a true story. I wrote it from the newspaper… Before the rousing encore he declares that:

…I wanna sing one song here recognizing that there are Goliath’s nowadays. And people don’t realize just who the Goliaths are but in older days Goliath was slayed and everybody looks back nowadays and sees how cruel Goliath was. Nowadays there are crueller Goliath’s who do crueler crueller things but one day they gonna be slain too… an’ people 2,000 years from now can look back an’ say remember when Goliath the second was slain…

When the Ship Comes In, performed so recently in front of the huge Washington march audience, could be said to be Dylan’s alternate version of Dr. King’s legendary speech. Dylan has a dream too, in which the forces of freedom and justice will rise up and defeat the evil ‘Goliaths’ of the day. Like King, Dylan employs quasi-Biblical rhetoric to get his triumphant point over.

The Carnegie Hall concert can be said to represent the high point of Dylan’s status as a political ‘spokesman’. He delivers this astonishing crop of new songs to an audience who are hearing them with fresh ears and who respond with unrestrained enthusiasm. Yet within a very short time rapid change was in the air. Just a few weeks later the ‘Murder Most Foul’ of John F. Kennedy was about to occur. Soon The Beatles would be arriving to ‘hold the hands’ of a shocked and grieving nation. The political battleground of the ‘60s was about to unfold, as Lyndon B. Johnson expanded the US’ involvement in Vietnam. Dylan, having advanced himself to a position as the ‘spokesman’ for the anger of his generation, was to react to all this with a raid volte-face. By the time of the Carnegie Hall show he had already written all of his ‘protest’ songs. Now his songs became more introspective, visionary and surreal, reflecting the fact that radical anti-establishment culture in the USA was soon about to take a very different turn. In this show, for a couple of intense and riveting hours, the twenty two year old Dylan encapsulates and defines the folk-protest movement of the early ‘60s, producing definitive performances of the songs that made him famous. These two hours can be said to define a particular moment in American history in which youthful radical opinion was united in a series of common causes. Here Dylan truly embodies the role of the bard, the public poet, in a fully committed way for perhaps the last time in his career. He is the boy David, the boy who will be King, who aims to destroy the behemoth of the military-industrial complex and the racist American establishment, aimed only with his puny catapult.

DAILY DYLAN NEWS at the wonderful EXPECTING RAIN

THE BOB DYLAN PROJECT- COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

Leave a Reply