“I is another. If the brass wakes the trumpet, it’s not its fault. That’s obvious to me: I witness the unfolding of my own thought: I watch it, I hear it: I make a stroke with the bow: the symphony begins in the depths, or springs with a bound onto the stage. If the old imbeciles hadn’t discovered only the false significance of Self, we wouldn’t have to now sweep away those millions of skeletons which have been piling up the products of their one-eyed intellect since time immemorial, and claiming themselves to be their authors!”

ARTHUR RIMBAUD

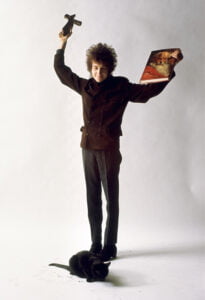

Desolation Row – A Hard Song to Sing

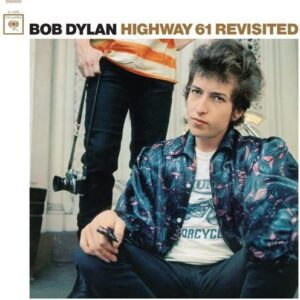

Desolation Row is a hard song to sing. It is undoubtedly one of Bob Dylan’s most profound, accomplished and ambitious compositions; full of poetic vitality, biting wit, unforgettable character sketches, literary and other allusions, distinctive rhymes and transcendent metaphors. The lyrics operate on many levels; as a commentary on the crazy hypocrisies of the modern world, as a declaration of the existence of the counter culture andas a literary manifesto. Despite its length (eleven minutes on its initial release) it has a clearly defined dramatic structure, including a clever framing device, within which it proceeds to a quite beautifully expressive climax. It is arguably Dylan’s most original and complete work – a song which could only have come from the particular historical moment and yet which is also completely timeless and full of universal truths. Yet, as the many unsuccessful attempts at recording the song (now available on the Bootleg Series release The Cutting Edge) demonstrate, Dylan struggled at first to place the tirade of astonishing lyrics in an appropriate musical setting. Although he has performed it many hundreds of times over his subsequent career, he has arguably never discovered an alternative arrangement that matches up to the sheer verbal and emotional power of the final Highway 61 take.

In 1965, Dylan was going through the most profound musical change of his career. Having made his name as a solo folk singer with a social conscience – a kind of updated version of his hero Woody Guthrie – he was then engaged in his highly controversial switch to becoming a rock star. While the previous record, Bringing it All Back Home, had begun the process, it was still divided between ‘acoustic’ and ‘electric’ sides. Now Dylan was attempting to cut an entirely electric album. Yet somehow Desolation Row does not quite fit the mould. For one thing, it has ten six line verses and lasted around eleven minutes. It takes the form of a traditional ballad, with many verses centred on a repeated musical pattern, with no bridge section or real chorus (although each verse ends dramatically with the title phrase). In many ways it could be seen as a successor to 1963’s apocalyptic A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall (a song which, perhaps surprisingly, later worked very effectively in a ‘rocked up’ form).

What kind of song is ‘Desolation Row’?

It is no exaggeration to claim that at this point in his career Dylan was actually in the process of reinventing the medium of song writing itself. He had immersed himself not only in old ballads and blues but also in the entire canon of Western literature, from Homer to Shakespeare to the Romantics, the Modernists and the Beat Poets. He was also in thrall to Elvis Presley, Little Richard, Buddy Holly and – lately – The Beatles. All of these influences now poured into his writing. But what kind of song is Desolation Row? Despite its musical form, with its stream of surreal images and eclectic cultural references it can hardly be called a ‘folk ballad’. It also has a basic rhythmic core which can set heads nodding and feet tapping. In many ways it is a rock and roll song. Yet to carry it off as a lyrical and rhythmic tour de force requires a particular effort of will. On the album’s bizarre ‘sleeve notes’ Dylan states that the record consists of …not so much songs but exercises in tonal breath control… It is almost as if, to perform this epic ‘recitation’, he has to take one extremely deep breath. The rest of the performance is a kind of long ‘exhalation’ which can only be achieved with intense concentration and focus. The singer needs to have quite extraordinary control of his diction and phrasing in order to make this convincing. Not surprisingly, there have been few cover versions of note.

The key to the success of the recording on Highway 61 Revisited was the addition of second acoustic guitarist Charlie McCoy, who later played with Dylan on Blonde on Blonde, John Wesley Harding and Nashville Skyline. Various attempts to record the song with electric guitars, drums and even piano proved unsuccessful. Finally the decision was made to go back to an acoustic guitar led recording. The addition of McCoy’s brightly inventive fills and, in particular, the little rhythmic flourish that comes at the end of each verse, drive the song along. Russ Savakas’ low key bass playing also helps anchor the sound. The result is a highly spirited performance, transforming a song which could be seen as doomy and depressing into a triumphantly uplifting hymn to the new rising consciousness of the mid ‘60s.

The Highway 61 Revisited album gives voice to this new perspective, for which Dylan had become the most articulate avatar. The forceful and imaginative Like a Rolling Stone, whichopens the album, celebrates this consciousness through what appears at first to be a personal ‘put down’ of a ‘spoiled rich girl’ but which turns into a mighty declaration of intellectual and spiritual independence. Tombstone Blues is a merciless satire on American cultural institutions. Ballad of a Thin Man is a devastating attack on a narrow minded individual who just cannot grasp what this new way of looking at life entails. The title song mocks the way that conventional religion is linked to warmongering. Queen Jane Approximately explores issues of sexual identity, while Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues outlines the effect of various ‘mind expanding’ drugs through the personas of Mexican prostitutes.

Just three years earlier, in the Cuban Missile Crisis, the world had held its breath on the brink of destruction. Meanwhile, Martin Luther King had expressed his ‘dream’, Kennedy had been shot, the US Army had been deployed in huge numbers in the unforgiving jungles of Vietnam and The Beatles had revolutionised American rock music. In the eyes of the burgeoning ‘youth movement’, the world was being run by leaders who were literally insane and every cultural shibboleth could now be challenged. Hard Rain had been a direct, if highly poetic, evocation of defiance of this madness in the face of an apocalypse.But now the discourse had shifted. It was now necessary to examine not just the mentality of war but the sickness of human culture and institutions that had brought the world to the precipice. A straightforward statement (like Barry McGuire’s inane hit Eve of Destruction or even Dylan’s polemical With God on Our Side) would no longer cut the mustard.

Desolation Row as Wasteland

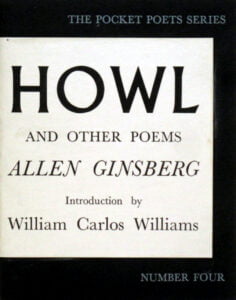

Desolation Row has frequently been compared to T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland, which examined the shifting of consciousness that occurred after the horrors of the First World War. Dylan even name checks Eliot in the song. But perhaps a more appropriate comparison is with Allen Ginsberg’s Howl, the visionary Beat poet’s brilliantly extended Whitmanesque rant against the shallowness of American post war culture. Howl famously begins: …I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness… which, in the light of the anti-establishment explosion of the 1960s, turned out to be extremely prophetic, as figures like Jim Morrison, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Brian Wilson, Brian Jones, Syd Barrett and Peter Green experienced psychological burnout or early tragic deaths.

ALLEN GINSBERG PERFORMS ‘HOWL’

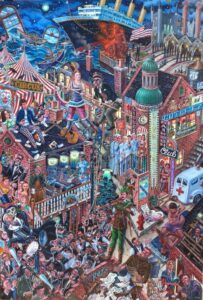

The songs on the Highway 61 album are each placed in dreamlike (or perhaps nightmarish) scenarios, in which a whole range of fantastical characters – from ‘Miss Lonely’ to ‘Napoleon in Rags’ to ‘Mr. Jones’ to ‘Sweet Melinda, the goddess of gloom’ appear and disappear rapidly. Some of these, like Ma Rainey, Beethoven, the King of the Philistines or Paul Revere are genuine historical figures. Others, like the ’Commander in Chief’, ‘Queen Jane’ or ‘the sword swallower’ seem to be satirical representations of real people. This ‘cinematic’ technique of allowing characters to appear, and then rapidly ‘cutting away’ from them, reaches its apotheosis in Desolation Row, which presents a long cavalcade of real historical figures and famous literary archetypes. Dylan places these characters, many of which are clearly symbolic, in bizarre or unfamiliar contexts. Despite their brief ‘cameos’, each one appears to take on a life of their own. They could be called ‘living symbols’.

Huge numbers of words have been written in the very many analyses of the song that have appeared, in which commentators have attempted to identify each character’s symbolic ‘meaning’, as if the song is some kind of puzzle that the listener is supposed to decode. But Dylan’s characterstake on a life of their own. Their interactions can (and of course have been) interpreted in many different ways.They are set up to be delightfully ambiguous. Dylan mixes a scathing critique of contemporary morals and beliefs with a tone of dark and ironic humour. When the song was first performed in 1965 to audiences who had never heard it before (as the album had yet to be released) they reacted by laughing as the witty lines and cutting rhymes poured out.

Another misunderstanding of Desolation Row which many commentators, attempting to place it in its literary context or to ‘justify’ it as a ‘serious work’, have perpetrated is that it is a ’modernist’ text. But although – like Beckett’s seminal modernist text Waiting for Godot – it delights in comic absurdity and ambiguity and like The Wasteland it is crammed with allusions, it steadfastly refuses to resign itself to the ultimate sense of hopelessness that such modernist texts convey. Dylan’s references to the modernists themselves, who actually appear as characters in the song, are decidedly mocking. Although to some extent he embraces modernism’s complex world view and uses some of its literary tropes and techniques, Whereas modernist texts like Joyce’s Ulysees and Finnegan’s Wake are deliberately constructed to be ‘difficult’,Desolation Row ultimately conveys a message of hope and positivity/ Ultimately the song conveys what could be called a Romanticist message, in that it focuses on the power of the imagination and uses certain gothic tropes.

Desolation Row as Romanticist Text

Just as Dylan is he is pushing song writing to its limits here, he is also simultaneously redefining modern poetry. He uses music, rhyme and rhythm to return poetic expression to its status as a popular art form. In doing so he creates a template which so many singer-poets, from Joni Mitchell to Leonard Cohen to Paul Simon to Richard Thompson, would follow. As Ginsberg – by now not only a friend of Dylan but a devoted admirer – recognised, this concept of the role of poetry had been one which he and the other Beat Poets had conceptualised in the 1950s. But their impassioned poetry readings to jazz backings had never reached the mass popularity of Dylan and his successors. In Desolation Row Dylan’s use of dream-narratives and fantastical scenarios also recalls the work of Blake, Shelley, Keats and the other Romantic poets. He takes complex, allusive and razor sharp poetry to into the homes of millions, creating art as resonant, universal and timeless as that of Shakespeare, to whom he quite naturally alludes in the song.

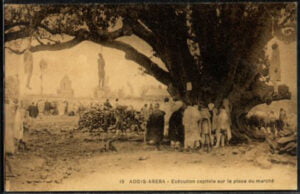

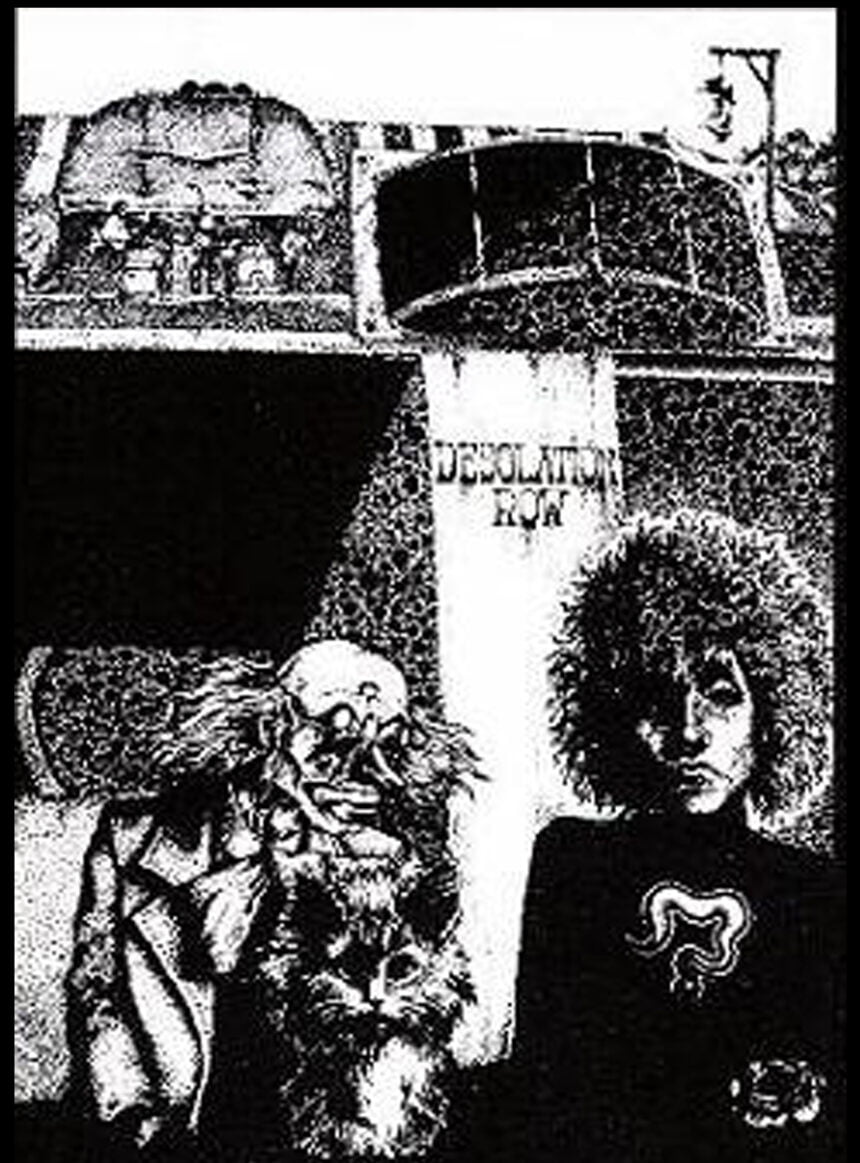

A POSTCARD OF THE HANGING

The first and final verses of Desolation Row form a kind of frame for its fantastical narratives, through which the action in the verses is filtered. The events of the song appear to take place within one evening, as night closes in. We begin with some of Dylan’s most evocative and mysterious opening lines: …They’re selling postcards of the hanging/ They’re painting the passports brown… The alliterative ‘ps’ here already have the effect of pushing the narrative forward positively and engaging the listener. The next lines: …The beauty parlor is filled with sailors/ The circus isin town… are similarly beguiling, with the ’ps’ now sliding into more reassuring ‘s’ sounds. Already, Dylan has built up a remarkable series of resonant visual images. The openinglines suggest a world in which rampant commercialism and crass bureaucracy has run riot. The first line has been linked to a real life event; a horrific lynching of two black men in Duluth (Dylan’s birthplace) in the 1920s. This may well be where Dylan got the inspiration for the line from. Postcards produced to ‘celebrate’ the event were actually sold at the time. But Dylan may also be referring to the way that violence is routinely commodified (and arguably celebrated) through the mass media. In just six words he paints a picture of a very sick world. The next line already takes us into more surreal territory, as the authorities apparently try to wipe out the proof of identity of those whoare marginalised in modern society. The succeeding lines paint a graphic picture of a world which is characterised as a kind of mad circus, in which normal reality is reversed. They counteract the repressive nature of the opening lines, taking us into the song’s vivid dream world.

The Circus is in Town…

Dylan is very fond of using circuses as metaphors. He also seems to like the sound of the word ‘circus’ itself. In Mr. Tambourine Man his protagonist is …circled by the circus sands…Ballad of a Thin Man includes a parade of ‘circus freaks’ and performers. It may be that all the events and characters in the song are actually part of a ‘circus’. This, it seems, is how Dylan views the modern world – as a fantastical show full of ‘performers’ desperately trying to impress us. Then we are introduced to the first character. The narrative tone shifts to that of a circus barker, who declares: …Here comes the blind commissioner… This figure appears to be some kind of generic authority figure, but he is also a circus performer. We are told that he is in some kind of trance and that …one hand is tied to the tightrope walker… It seems that he has been made to ‘walk the tightrope’ –obviously a very perilous task for a blind person to be asked to do. But in case we have any sympathy for him, Dylan undercuts this with vicious humour …the other is in his pants… which may be a sexual reference but could also imply that this official is ‘trousering’ any profits from the circus. So he may be a symbol of ‘blind’, directionless but corrupt authority. Or he may just be ‘playing with himself’.

The concluding lines: …And the riot squad, they’re restless/ They need somewhere to go/ As Lady and I look out tonight from Desolation Row…continue the‘t’ alliterationfrom the line about the ‘tight rope walker’. The notion of a ‘restless’ riot squad now pushes the narrative in a more socio-political direction; the inference being that the ‘squad’ is basically a bunch of thugs spoiling for a fight. In the context of the 1960s civil rights movement and the viciously racist policing that protesters were often met with, this seems particularly apposite. So far we have been given a picture of a topsy-turvy, corrupt world, elements of which are nevertheless presented as popular entertainment to the ‘brainwashed’ population. It is important to note, however, that the world that is being described is not ‘Desolation Row’ itself. Here we see the narrator and his ‘Lady’ looking at this mad world from that place. This will be consistent throughout the song. ‘Desolation Row’ is in fact a place of refuge; the only place where sanity and true humanity can be found. This may seem somewhat contradictory, but the world being described here – whatever its drawbacks – is hardly ‘desolate’.

Desolation…

The term ‘desolation’ can be strongly identified with the notion of being ‘beat’, which Kerouac, Ginsberg and others advanced as a measure of the degradation and ‘madness’ they felt they had to put themselves through to truly break away from the mind set of conventional society. Kerouac’s stream-of-consciousness novel Desolation Angels had recently been published and Dylan – ever the magpie – lifts several lines from it in this song. ‘Desolation Row’ is, of course, a state of mind rather than a physical location. It represents a place which is not necessarily easy to get to. Top reach it one must, perhaps, be ready to subject oneself to a ‘desolate’ existence, perhaps by pushing oneself to mental extremes. But it appears to be the only place from which one can really appreciate just how twisted and crazy the ‘real world’ has become.

The next eight verses introduce us to a cavalcade of characters, who may or may not double as circus performers. Dylan sums up each of their qualities succinctly, with mordant wit. We begin in the world of fairytales, with Cinderella, in a story which advances the idea that true human worth (in the form of the honest, but put-upon servant girl) must triumph over wealth and narcissism (as epitomised by the heroine’s ugly sisters). But the character who we meet here certainly does not seem to be waiting for Prince Charming or expecting any magical transformations. We are told that …she seems so easy… and that, in a delicately ifrather suggestively. executed turn of phrase: ….”It takes one to know one”, she smiles… Then, in a quite brilliantly visual transformation, we hear that…Then she puts her hands in her back pockets/ Bette Davis style…This is a modern, ‘liberated’ Cinderella, presumably dressed in jeans. ‘She seems so easy’ may suggest a woman who is particularly sexually active. The actress Bette Davis, who specialised in powerful female roles in which she displayed an independent sexuality, really did have a habit of putting her hands in her back pocket.

BETTE DAVIS

Suddenly Romeo, who seems to be a rather pathetic figure, appears – apparently in pursuit of Cinderella: …In comes Romeo, he’s moaning/ “You belong to me, I believe”… Thismay be a reference to You Belong to Me, a moving if lachrymose ballad first recorded by Jo Stafford in 1952 and later by Dean Martin, Patsy Cline and many others. Dylan recorded his own version for the soundtrack of Natural Born Killers in 1992. But, as is pointed out to the anguished lover, he is ‘in the wrong place’. Naturally he should be pursuing Juliet, not Cinderella. The verse ends ominously: …The only sound that’s left/ After the ambulances go/ Is Cinderella sweeping up/ on Desolation Row… We may speculate that Romeo, who of course kills himself in Shakespeare’s play, has committed suicide. Or perhaps he has been removed to an asylum. In any case, Cinderella carries on regardless. She is protected from the vagaries of this shifting dream world because she lives ‘on Desolation Row’. But the clearly confused lover Romeo appears to have wondered into the wrong narrative entirely, again indicating that these characters exist in a world where everything is slightly askew.

ROMEO AND CINDERELLA

The Stars are Beginning to Hide…

We now see that the sun has gone down and that the evening’s revelries are about to begin. But something in the universe is ‘out of joint’. We hear that …the moon is almost hidden/ The stars are beginning to hide… as if these natural features are somehow alive but are hiding themselves away, as if in shame. …The fortune telling lady has taken all her things inside… suggests that any conventional prediction of the future is unlikely to be accurate as an apocalyptic event is about to occur. The following:…All except for Cain and Abel/ And the Hunchback of Notre Dame/ Everybody’s making love/ Or else expecting rain… is tantalisingly ambiguous. It seems that the population of the world of the song are either frantically taking their last chances to make love before the end comes or just sitting around hopelessly, waiting for it to happen.

CHARLES LAUGHTON AS THE HUNCHBACK OF NOTRE DAME

More strange juxtapositions of characters from different origins then occur. The Biblical Cain and Abel are lumped together with Victor Hugo’s eponymous bell-ringer. In Genesis, Cain and Abel are the sons of Adam and Eve and Cain becomes the first murderer when he kills his brother before being exiled to ‘walk the earth’ to atone for this (perhaps unforgiveable) sin. Quasimodo the hunchback is another tragic figure who is powerless to save Esmeralda, the girl he is besotted with, from the gallows. In his rage he throws the archdeacon Frollo, who was also in love with the girl, from the tower of the cathedral to his death. The implication here appears to be that these characters are somehow detached from the world of the song, being so bound up in their own tragic lives that they will not be able to participate in the coming festivities. The final lines of the verse, however, introduce another Biblical figure, the Good Samaritan (who in the New Testament saves a dying man without prejudice when other pass him by) and who is happily preparing himself for tonight’s carnival on Desolation Row, an event to which Cinderella and Romeo have not been invited. But our ‘grown up’ Cinderella, however, does not seem bothered that she will not be ‘going to the ball’.

THE GOOD SAMARITAN

Each of the next three verses is based around a single symbolic character. First of all we meet Ophelia (Hamlet’s doomed girlfriend who commits suicide in Shakespeare’s play after Hamlet kills her father Polonius). This is one of the song’s more detailed ‘character studies’. Again the action described occurs in a dreamlike scenario in which the conventional attributes of the characters are mixed up. Ophelia is first seen …’neath the window… which is where Romeo should perhaps have been in the last verse, serenading Juliet. The narrator expresses concern for her: …For her I feel so afraid… which is followed by the extraordinary statement …On her twenty second birthday, she already is an old maid… Shakespeare infers that Hamlet and Ophelia have had sex. As the apparently crazed Hamlet rejects her, she can no longer marry – according to the morality of the time – because she is no longer a virgin.

OPHELIA

Ophelia’s Neath the Window

What follows is an extraordinary set of images, which can be read in a number of ways. We are told that …to her, death is quite romantic… and that she …wears an iron vest… It may be that the ’Ophelia’ figure here is, like the earlier Cinderella, actually a modern woman. She appears to represent a figure who, because of her devotion to the constraints of the ‘iron vest’ of sexually repressive organised religion, can never enter the ‘sanctuary’ of Desolation Row. She considers herself a sinner who cannot be saved and will eventually, like Romeo, take her own life. But, in one of the song’s most remarkable lines, we are given the icily ambiguous: …Her profession’s her religion/ Her sin is her lifelessness…This seems to refer to the conversation between Hamlet and Ophelia in which he (pretending to be mad) tells her to go away from him and …Get thee to a nunnery…This is usually taken to indicate that Hamlet is cruelly rejecting her and suggesting that she is nothing but a whore (‘nunnery being contemporary slang for a brothel).Thus Ophelia as portrayed here represents the opposite of Cinderella – a woman who cannot break down the barriers of sexual repression and guilt that the established church has erected around her. Yet the final lines of the verse indicate that, though she patiently waits for God’s forgiveness, with her eyes …fixed on Noah’s great rainbow… the Old Testament sign of the covenant between God and man, she is continually tempted to ‘peek’ into the supposedly sinful and immoral Desolation Row.

Dylan’s treatment of Ophelia seems to suggest that she represents the way in which conventional Christianity, with its strong emphasis on sexual repression and condemnation of female sexuality, prevents its‘victims’ from entering the more liberated and enlightened state that Desolation Row represents. It is this institutionalised repression that creates the state of ‘lifelessness’ that Ophelia trapped in. The highly resonant phrase ‘her sin is her lifelessness’ is borrowed from Kerouac’s Desolation Angels, representing the state of mind which the Beat poets fought passionately against.

NOAH’S GREAT RAINBOW

Einstein ‘goes electric’

The next verse concerns another symbolic figure in the person of Albert Einstein, the most famous scientist of the twentieth century and a highly enlightened figure, whose very name has become a byword for ‘genius’. Yet the great man is shown here as being reduced to the level of a street beggar who is …disguised as Robin Hood… and is accompanied by …his friend, a jealous monk… Perhaps this ‘friend’ is Robin Hood’s sidekick Friar Tuck, although the fact that the monk is called ‘jealous’ appears to be another personification of repressive organised religion. In a wonderful collocation of words Dylan describes Einstein as looking …so immaculately frightful/ As he bummed a cigarette… ‘‘Frightful’ and ‘immaculate’ are supposedly opposing terms. The suggestion seems to be that Einstein is extremely proud of his down at heel state. He has ‘dropped out’ of conventional society and become an ‘outlaw’. Yet he has certainly lowered himself into extreme degradation: …He went off sniffing drainpipes/ And reciting the alphabet… In a last, darkly comic twist, Dylan’s narrator shares with us that …You would not think to look at him/ But he was famous long ago/ For playing electric violin on Desolation Row… Within the degraded world that is being described, a celebrated prodigy is reduced to the status of a hobo, grubbing around for scraps. Einstein really did play the violin as a hobby, although Dylan’s insertion of ‘electric’ here seems to reflect Dylan’s own current transformation via ‘electric’ instruments. On one level, this Einstein/outlaw figure might be seen as Dylan himself – a ground breaking genius who dresses like a bum.

EINSTEIN WITH VIOLIN

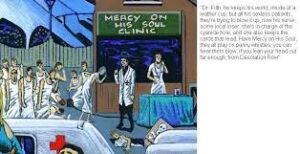

Dr. Filth and the Nurse

From here on, the song takes some darker turns. The subject of the following verse, ‘Dr. Filth’ who …keeps his world inside of a leather cup… is distinctly scary figure – a personification of the perverted science which dominates the world under observation from Desolation Row. The image of a leather cup may suggest the testicular protection device worn by American Footballers. In any case it seems that the ‘dirty doctor’ has control of a world which is dangerously shrunken. The Doctor himself seems to be some kind of combination of Sigmund Freud and Josef Mengele. We hear that his ‘sexless patients’ would like to destroy the Doctor’s world but are presumably powerless to do so. The Doctor is assisted by a nurse with equally dubious morality, memorably put down by the narrator as …some local loser… In a scathingly surreal line she is said to be…in charge of the cyanide hole… which may be some kind of device through which people’s minds are ‘poisoned’. But the nurse also controls the doctor as she …keeps the cards that read ‘Have mercy on his soul’… She is in charge, it seems, of his potential chances for salvation. Both of these ‘medical’ figures are said to ‘blow’ rather hopelessly on ‘penny whistles’ which those of us in Desolation Row can hear if we ‘lean our heads out far enough’. The attempts by these sick and twisted characters to express themselves are thin and reedy. In this verse, the Doctor and the Nurse are the opposite of what they are supposed to be. They are sadistic killers rather than healers. Viewed from Desolation Row, the contrary nature of this vision of the world now becomes clear.

SIGMUND FREUD

As the night wears on, preparations for some kind of celebration continue. We are told that the ubiquitous ‘they’ are …getting ready for the feast…. Now we meet The Phantom of the Opera, another famous literary character whose story has been adapted many times on screen and in print. Originally published as a novel in 1911 by Gaston Leroux, the tragic story of its doomed protagonist, who the world will not accept because of physical deformity has been adapted in a number of films and stage musicals. As a character the Phantom thus resembles the Hunchback of Notre Dame, both of whom ‘haunt’ famous buildings in Paris. Here he is described, in another line taken from Desolation Angels, as looking like …the perfect image of a priest… another apparently paradoxical image recalling the earlier description of Einstein ‘the bum’ as ‘immaculately frightful’.

THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA

Casanova is Punished…

It seems that the Phantom has been placed in charge of organising the upcoming celebrations, which turn out to consist of nothing less than a ritual murder of another famous legendary figure: ..They’re spoon feeding Casanova/ To get him to feel more assured… In an earlier version Casanova is force fed …the boiled guts of birds…. This gruesome image might fit more with the grand guignol setting, but the change of lyric is more subtle, indicating that the famous lover is being ‘set up’ by unknown shady figures – the song’s ubiquitous ‘they’ – so that they can …kill him with self confidence/ After poisoning him with words…Casanova was a real historical figure whose (quite possibly highly exaggerated) memoir claimed he had bedded thousands of women. He has since become a symbol of male sexuality – the ultimate ‘romantic’. Now we see him being subsumed by the powers that be. His sexual indulgences have brought about his ruin. As the Phantom angrily tells the ‘skinny girls’ (presumably some of Casanova’s conquests) who have come to visit him …Get out of here if you don’t know/ Casanova is just being punished for going to Desolation Row… Thus Desolation Row is associated with the sexual freedom that Casanova seeks.

CASANOVA

The Superhuman Crew

Images of repression build up in the powerful eighth verse. We now reach the climax of the evening’s entertainment. Dylan’s words drip with bile: …At midnight all the agents/ And the superhuman crew/ Come out and round up everyone/ That knows more than they do… This paints a picture of a totalitarian state. In using ‘superhuman’ Dylan hints that these ‘goons’ may, like the Nazis, consider themselvesto be members of a superior race. But the ironic placing of the word ‘crew’ shifts the image into a comic book scenario. The killer line here is the last of the four, a brilliantly compressed comment that implies that the repression being handed out is directed at intellectuals, very much as it has been in many totalitarian states. But this scene, with its comic book connotations, does not appear to be taking place in some ’far off land’. It is happening in contemporary America, from which Desolation Row provides the only shelter. In this context, the street violence that plagued the US in the 1960s during the battles over civil rights (for which Dylan himself had written the most potent anthems) is a constant backdrop. But in the scenario which is unfolding, state repression is now spreading to all those who oppose it.

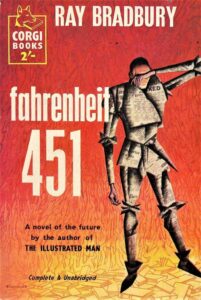

KAFKA

The tortures that are now recounted leave us in little doubt as to the power of those repressive forces: ...And they bring them to the factory/ Where the heart attack machine/ Is strapped across their shoulders… The bland ambiguity of the terms ‘the factory’ and ‘the heart attack machine’ is thrown into relief by the way Dylan uses enjambement so sharply …and then the kerosene… he drawls …is brought down from the castles/ By insurance men who go/ Check to see that nobody is escaping to Desolation Row…The pointed use of ‘kerosene’ to link the lines together recalls Ray Bradbury’s dystopian satire Fahrenheit 451, in which all books are burned by kerosene-wielding operatives. The references to ‘castles’ and ‘insurance men’ are direct allusions to Franz Kafka’s terrifying dystopian tales of repressive state bureaucracy. The way Dylan balances terror and sly wit in this verse is quite masterful. When the song was later shortened for live performances, this verse was always retained. It is Dylan’s most powerfully cynical indictment of the ‘straight world’. Here the ‘insurance men’ – bland besuited bureaucrats – attempt to reduce the range of human experience and place individuals in fear of living life the full. In this song, there is only one place in the modern world where it is possible to do this. And that, of course, is Desolation Row.

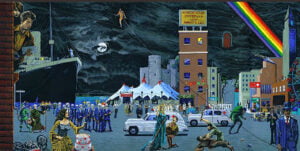

Now that the world that the Row’s protagonists are looking into has revealed itself to be vicious and controlling, the narrator takes a step back and comments wryly on the state of the modern world. …Praise be to Nero’s Neptune!…he exclaims …the Titanic sails at dawn/ And everybody’s shouting/ “Which side are you on?”… The emporer Nero has the reputation of being insane, and was famously said to have ‘fiddled while Rome burned’. A coin has been discovered with Nero’s head and one side and a representation of the harbour of Ostia on the other. Prominent in the picture is a statue of Neptune, the god of the sea. It may be that the world is being pushed towards destruction, perhaps by another Great Flood, despite the earlier presence of ‘Noah’s great rainbow’.

EMPORER NERO

What Side are You On?

The Titanic is, of course doomed. Here it may stand for the whole of human civilisation, driven by Neptune’s winds to an inevitable end. Meanwhile the passengers are fighting and arguing about political ideologies. Dylan’s choice of the phrase ‘Which side are you on’ is especially relevant as it is the title of one of America’s most famous protestsongs, written in 1931 by labour activist Florence Reese. Later recorded by Pete Seeger and many others, it was still a staple of Greenwich Village folk singers when Dylan arrived there. It is, however, a rather crass song which lacks the subtle nuances of Dylan’s own protest material. The juxtapositioning of these elements throws the futility of the protestors’ song into a sharp light here. Throughout Desolation Row there have been hints than an apocalyptic destruction of the nightmarish world it describes is imminent. The utter pointlessness of adopting a political position in such circumstances is made clear here.

TITANIC

Another brief couplet demonstrates how famous writers are also wasting their time in pointless textual disputes which will be equally useless in preventing the cataclysm to come. Dylan tells us that: … Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot… are… Fighting in the captain’s tower… Here we see two leading exponents of modernist literature locked in a pointless dispute. The ’captain’s tower’ appears to refer to the tower in Dublin in which the opening chapters of James Joyce’s Ulysees are set. The implication seems to be that the over-intellectualised linguistic puzzles of such modernist works will prove to be useless for preventing the coming disaster. But then the tone suddenly shifts. While the intellectuals fight their pointless battles, we hear that …calypso singers laugh at them/ While fishermen hold flowers… The calypso singers and fishermen live in a beautiful world of fantasy: …Between the windows of the sea/ Where lovely mermaids flow/ And nobody has to think too much/ About Desolation Row…

TS ELIOT AND EZRA POUND – THE CAPTAIN’S TOWER

Although Desolation Row appears to suggest that a coming apocalypse is imminent, the notion that this will be a nuclear war – which Dylan had railed against in his earlier, more prosaic protest song Let Me Die in My Footsteps and his visionary A Hard Rain’ a-Gonna Fall, is only one possible interpretation. The narrator’s series of dream visions also suggest that a revolution of consciousness may be coming, inspired by the denizens of Desolation Row and perhaps by those loving ‘fishers of men’ accompanied by the ‘lovely mermaids’. In the meantime, escaping to this isolated place appears to be the only way to stay sane.

HAVE MERCY ON HIS SOUL

I Received Your Letter Yesterday…

A verse-long harmonica break separates this from the final verse, which completes the framing device. Now Dylan reverts to a more detached, prosaic voice of an ‘I’ narrator, giving us what at first seems to be rather trivial and irrelevant information: …I received your letter yesterday/ About the time the door knob broke/ If you asked me what I was doing/ Was that some kind of joke… It seems that the narrator is referring to a moment when he was trapped in some unspecified room. But the last two of the four lines appears to aska somewhat pointless question. Of course he was trying to escape. It now appears that all the previous action of the song made up the contents of this letter. But then the narrator turns everything around: …All these people that you mentioned/ I know them, they’re quite lame/ I had to rearrange their faces/ And give them all another name…This adds a whole new dimension to the song. It may be that the parade of mythical, literary or historical figures we have been presented with are more ciphers for actual people that the two correspondents actually know. But the narrator has decided to mythologise them by giving then the names of famous representative figures. Finally he instructs us not to send him any more letters: …not unless you mail them from Desolation Row… Only by embracing this ‘desolation’, this state of being ‘beat’, can true communication occur. On a political level, this appears to involve transcending failed ideologies. On a personal level, true intellectual and spiritual freedom can only be achieved by removing oneself steadfastly from the dominant morals and values of the culture.

Desolation Row is thus without a doubt one of the key texts – arguably the key text – of the 1960s counter culture. It creates an image of a ’place’ to which those who are horrified by the violence, cruelty and religious and political hypocrisy in the world can retreat. The ‘row’ is a strange place, in which reality is constantly shifting, while the nature of that reality is necessarily ambiguous. It is a location in which poetic metaphor and dream images are reality and from which a new world free from terror, repression, bigotry and violence – like Coleridge’s Xanadu – can be created. Entering it may not be easy. We may not even know we are there when we get there. But it is vital that, in order to become a creative artist rather than a mere entertainer, one must embrace personal ‘desolation’ – in other words, to reach into the darkest depths of one’s soul, at a place where heroes look like hoboes and ordinary people turn into mythical characters, in order to unleash the power of one’s imagination on the world.

LINKS…

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

THE CAMBRIDGE BOB DYLAN SOCIETY

Leave a Reply