…I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked,

dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix,

angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery

of night…

Allen Ginsberg, Howl, 1956

…My solution to the problem would be to tell them frankly that they’ve got to draw in their horns and stop their aggression or we’re going to bomb them back into the Stone Ages….

General Curtis E. LeMay, in Mission With LeMay, 1965.

TOMBSTONE BLUES

Tombstone Blues is one of Bob Dylan’s funniest songs, filled with sharp one liners, even if, as the title suggests, the humour is sometimes that of the graveyard. It presents a satirical view of the mores of contemporary America which is peopled by present day, historical, mythical and Biblical figures who interact in bizarre ways. As in Subterranean Homesick Blues, Dylan cocks a snook at a number of treasured American values and institutions, placing them in unfamiliar and sometimes surreal contexts. But here the critique of such values is even more focused and unrelenting. The title Tombstone Blues seems at first to indicate some kind of death obsession. It is worth mentioning, however, that Tombstone, Arizona is one of the most frequently featured locations in Westerns, that most American of mythological settings.

TOMBSTONE ARIZONA

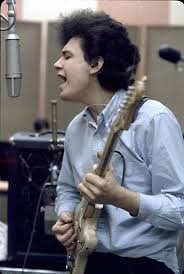

In the originally released recording on Highway 61 Revisited (1965) the song is fired up by inspired incendiary blues solos by the brilliant guitar prodigy Mike Bloomfield. First premiered in an acoustic version in a workshop at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965, it was then recorded a few weeks later, acquiring a dynamic new electric setting, a new melody and a distinctive, stinging chorus. Various versions which appear on the Bootleg Series release The Cutting Edge trace its evolution into a noisy if somewhat deliriously crazed rock anthem. It has been played around 150 times in concert, appearing as a standard selection on the 1984 tour and in many Never Ending Tour gigs from 1995 onwards. Within these performances the arrangement and lyrics undergo little change, although the version recorded for Shadow Kingdom in 2021 is more thoughtful and uncharacteristically subdued. Mostly, though, Dylan treats the song as a delirious romp which is a vehicle for his distinctively acidic wit

.

MIKE BLOOMFIELD

I’m in the kitchen with the Tombstone Blues

The chorus appears to present the narrator as a member of a poverty stricken family: …Mama’s in the factory, she ain’t got no shoes/ Daddy’s in the alley, he’s looking for food/ I’m in the kitchen with the Tombstone Blues… In later live versions the Daddy is ‘looking for the fuse’ – a more precise rhyming line but one which makes less sense in context. In adopting a typical blues singer’s rhetorical stance, Dylan, however, does not expect us to take such declarations seriously. The chorus also resembles that of Woody Guthrie’s Talkin’ Blues, which depicts a colourful description of a family of bootleggers: …Mamma’s in the kitchen fixin’ the yeast/ Poppa’s in the bedroom greasin’ his feet/ Sister’s in the cellar squeezin’ up the hops/ Brother’s in the window just a-watchin’ for the cops… Dylan’s adaptation is equally tongue in cheek, although his chorus is a line shorter to allow for the prominent guitar solos.

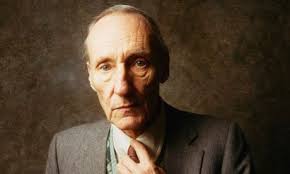

There are six pairs of two verses in the song, each consisting of three rhyming lines and a final line which rhymes with the last line of the succeeding verse. To some extent this structure follows the ‘talkin’ blues’ format, with the insistent rhyming allowing for comic exaggeration and the final line making a dramatic, and often sardonic, comment on the rest of the verse. Like Subterranean Homesick Blues, the song is also influenced by the quick-fire tongue-in-cheek wit of Chuck Berry in songs like Back in the USA and You Never Can Tell. The various individuals who inhabit the verses make only fleeting appearances. As with the numerous characters in Desolation Row and Highway 61 Revisited many of them can be seen as symbolic representations of established values or beliefs. Here Dylan clearly relishes placing such characters in weird juxtapositions in a caustically funny way that sometimes echoes the anarchic wordplay of Beat novelist William Burroughs. Its anti-establishment bent is clear from the beginning. It cannot, however, be labelled a ‘protest song’. No direct observations on inequalities in American society are made. Dylan’s concern here is rather to satirise the mentality of a range of conventional thoughts and attitudes and thus to expose their essential hollowness.

WILLIAM BURROUGHS

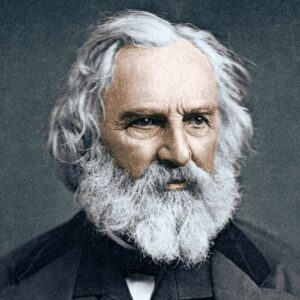

We begin with ….The sweet pretty things are in bed now of course… which sounds like a twisted version of a line from a Disney movie, as if the singer is referring to sleeping ‘cartoon children’ or perhaps the Seven Dwarfs. This is immediately set against an absurdist reference to American history: …The city fathers are trying to endorse/ The reincarnation of Paul Revere’s horse… Local patriarchs are, it seems, engaged in a ridiculous attempt to revive the spirit of the American Revolution, of which the famous ‘ride of Paul Revere’ to warn the American insurgents of British troop movements is supposed to have played a key role. Revere’s ride entered American patriotic mythology when Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem Paul Revere’s Ride (which exaggerated the importance of Revere’s exploits for poetic effect) was published in 1861. Here Dylan’s ire is directed at the way American local government officials try to ‘wrap themselves in the flag’, as indicated by the ironic payoff line …But the town has no need to be nervous…. Another ‘revolution’ is clearly not about to occur…

PAUL REVERE’S RIDE HENRY WADSWORTH LONGFELLOW

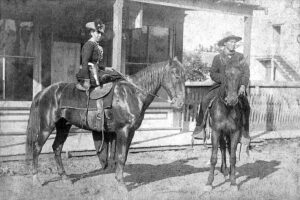

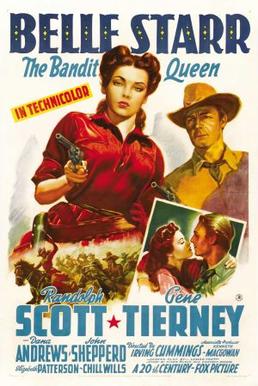

Three more ‘historical’ characters are then introduced in quick succession. We are told that …The ghost of Belle Starr she hands down her wits/ To Jezebel, a nun, who violently knits/ A bald wig for Jack the Ripper who sits/ At the head of the Chamber of Commerce… Belle Starr was an associate of Wild West outlaws such as Jesse James. Over the years her story, like that of other ‘Western cowgirls’ like Annie Oakley and Calamity Jane, has been heavily mythologised in comics, dime store novels and Hollywood movies which portray her as a fearless and bloodthirsty whisky-swilling gunslinger. Jezebel is an Old Testament figure from the Book of Kings who has come to symbolise female treachery and licentiousness. Dylan appears to delight in the sacrilegious joke of making her a nun. The rest of the verse descends into extreme comic absurdity, as Jezebel ‘violently knits’ (an apparent contradiction in terms) a bald wig for the famous serial killer who now is apparently a highly respectable businessman. Perhaps the Ripper heads a local business organisation but he may even be leading the US Chamber of Commerce, the world’s largest and most influential business organisation and a potent symbol of American capitalism. By placing this notorious (and again highly mythologised) figure in such a position, Dylan gleefully establishes a darkly comic link between capitalism and the violence which is endemic in American society and culture.

BELLE STARR

We then switch rapidly to another scene involving a ‘hysterical bride’, a doctor and a ‘medicine man’. The ‘hysterical bride’ is placed in a typical American setting – a ‘penny arcade’ (a symbol, perhaps of ‘cheap’ hucksterist capitalism). She is also a Freudian stereotype, whose line …Screaming, she moans, “I’ve just been made”… appears to indicate her fear of sexuality. A doctor (who may well be a psychiatrist) then arrives and …pulls down the shades… shielding her from the prying eyes of the outside world. His advice is to …not let the boys in… which merely appears to reinforce her phobia. But this pronouncement is mocked by the ‘medicine man’ (another stock figure in Western films) who tells her in no uncertain terms to …Stop all your weeping, swallow your pride/ You will not die, it’s not poison… Here Dylan appears to be poking fun at the confusion about sexuality caused by the intersection of traditional American Puritanism and the rise to prominence of Freudian psychology – two obviously contradictory viewpoints symbolised by the two diametrically opposed ‘healers’.

In the following verses, Dylan mercilessly mocks the mentality of American militarism. First of all we get to hear a conversation between John the Baptist (in the original lyrics, ‘John the Blacksmith’) and his ‘Commander in Chief’. It is pretty certain that this is not the Biblical prophet John as the first reference has him ‘torturing a thief’. We then hear that …He looks up at his hero, the Commander in Chief/ Saying “Tell me great hero, but please make it brief/ Is there a hole for me to get sick in... It appears that ‘John the Baptist’ must be an alias for some military operative who apparently is disgusted with his own work in the ‘dirty tricks’ department. In the next brilliantly sardonic comic concoction, Dylan mocks the military mentality with withering scorn. First we hear that …The Commander-in-Chief answers him while chasing a fly/ Saying “Death to all those who would whimper and cry!”… Here the ‘commander’s over the top macho declaration is directed most laughably at nothing but a common house fly. Then Dylan delivers his knockout punch: …Dropping a barbell he points out the sky/ And says “The sun’s not yellow, it’s chicken!”… The Commander, who is engaged in muscle building callisthenics, seemingly now wants to declare war on the sun, which he declares is a coward. The punch line is given extra resonance because in the USA the term ‘Commander in Chief’ is often used to describe the President.

‘THE SUN’S NOT YELLOW…’

The military theme, again with a bizarrely Biblical slant, continues with …The King of the Philistines, his soldiers to save/ Puts jawbones on their tombstones and flatters their graves…. In the book of Judges the Jewish strongman Samson fights the Philistines and in one battle is said to kill thousands of the enemy soldiers with a jawbone. Here we might suspect that the King could well be identified with the Commander in Chief from the previous verse. The description certainly seems to be that of a tyrannical ruler who uses weasel words to persuade his soldiers to fight for him. A ‘Philistine’ is also a term for a person whose aesthetic sensibilities are particularly crass. Many commentators have argued that Dylan is making a coded reference to Lyndon B. Johnson, then the US President, who had recently engaged in a massive escalation of the war in Vietnam. This assumption may well be supported by the following lines …Puts the pied pipers in prison and fattens the slaves/ And sends them out to the jungle… if one reads the ‘pied pipers’ as anti-war protestors and the ‘slaves’ as conscripted soldiers. Dylan’s framing of themes of military coercion in pseudo-Biblical terminology can be seen as especially effective given the protestations of religious belief that so called American patriots – then and now – tend to hide behind.

LYNDON B. JOHNSON

Another mythic figure – Gypsy Davy, the romantic protagonist of a Scottish ballad (given an American slant in Woody Guthrie’s adaptation) who runs off with the King’s daughter – is then introduced. But this ‘fake hero’ is actually another murderous military operative. Accompanied by his ‘faithful slave Pedro’ (Possibly a rather obscure reference to Sancho Panza in Don Quixote) and armed with a blowtorch he is said to have …burned out their camps… He is said to have …a fantastic collection of stamps… which have presumably appeared on his passport as he has travelled around the world in order to …win friends and influence his uncle… We may assume, given the general drift of the themes of the song, that the ‘uncle’ he is trying to impress is none other than Uncle Sam, the symbolic embodiment of American military power.

UNCLE SAM

We then hear that …The geometry of innocent flesh on the bone/ Causes Galileo’s math book to get thrown/ At Delilah who’s sitting worthlessly alone/ But the tears on her cheeks are from laughter… Here Dylan juxtaposes Galileo (a real historical figure who is often seen as the founder of modern science but who was persecuted by the Catholic Church for conducting his empirical experiments) with the Biblical Delilah, the wife of Samson, whose cutting of her husband’s hair presages his defeat by the Philistines. Delilah appears to be a cynical, uncaring figure here who is far from ‘innocent’, despite Galileo’s attempt to analyse the ‘geometry’ of her face. Science, it seems, can only be of so much use in dealing with the darker human emotions.

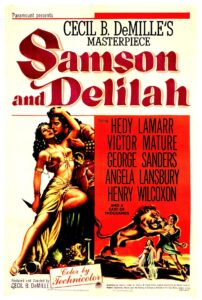

Dylan then takes aim at one of his favourite targets – the commercial exploitation of religion (as so mercilessly described in the phrase …flesh-colored Christs that glow in the dark… in It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding). He declares that …I wish I could give Brother Bill his great thrill/ I would set him in chains at the top of the hill/ Then send out for some pillars and Cecil B. De Mille/ He would die happily ever after… There seems little doubt here that he is referring to the world famous evangelist Billy Graham, who was known for conducting vast prayer meetings in sports stadiums and on television. The fake pomposity of this kind of mass religion is satirised by referring to the Hollywood director Cecil B. De Mille, famed for his grandiose Biblical epics such as The King of Kings (1927) and his two versions of The Ten Commandments (1923 and 1956) De Mille, it seems, would be ideal director to present ‘Brother Bill’s version of mass commercialised religion. Implicit in these lines is the highly sarcastic implication that Brother Bill will embrace death (rather than life) quite happily, which in itself appears to be a rather vicious jibe at Christians who fetishise the crucifixion rather than Jesus’ teachings. Graham himself was something of a contradictory figure. A confidante of Martin Luther King, he refused to preach to racially segregated congregations. But he was also a friend of the President and a prominent supporter of the war in Vietnam.

‘BROTHER BILL’

Dylan then targets more revered institutions. He presents a highly comical picture of Beethoven (the epitome, of course, of the highest intellectual achievements in classical music) ‘unwrapping a bedroll’ with Ma Rainey, the great blues singer of the 1920s but laments that the combined legacy of these musical giants is now reduced to the empty patriotism of ‘tuba players rehearsing’ …around the flagpole… While the concluding verse is a mere coda, in which the narrator appears to imply that he has actually been conducting an address to a confused ingénue whose ‘useless and pointless knowledge’ is driving her insane, it is in the concluding lines from the penultimate verse in which Dylan sums up the overall themes of the song. In a highly caustic jibe at American institutions, he declares …And the National Bank at a profit sells road maps to the soul/ To the old folks home and the college… summarising various ways in which American capitalists exploit religious and educational impulses and even dreams of peaceful retirement to make money.

LUDWIG VAN AND MA RAINEY

Tombstone Blues is an anarchic rant against all forms of institutionalisation – by the military, by religious ‘leaders’, by educators, business men and civic administrators. Dylan himself was a college dropout who educated himself through his intense fascination with music and literature. Inspired by the untrammelled spirit of the Beat poets and fuelled by the vengeful dark humour of the blues tradition, he here delivers a heartfelt and unforgettable demand for intellectual and spiritual freedom which was to inspire many listeners to institute their own personal ‘declarations of independence’ from the many manifestations of the fake ‘American dream’ which the song castigates with such biting wit and devastating comic force.

Leave a Reply