Bob Dylan has written many love songs in his career, many of which, like Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right or One of Us Must Know, adopt a resigned or philosophical approach to a failed relationship. Some, like Girl from the North Country or Boots of Spanish Leather, take a more romantic, if distanced, approach. A few, like It Ain’t Me, Babe or Just Like a Woman are songs of rejection. During his ‘years of domestic retreat’ he composed more straightforward songs of devotion like The Man in Me, If Not For You or Lay, Lady Lay. Because of his considerable fame and his consequent (if highly reluctant) status as a celebrity, many commentators have sought to link particular songs to his known relationships. So we are told that Girl from the North Country is ‘about’ Echo Helstrom, his teenage ‘old flame’, Boots of Spanish Leather is ‘about’ his early 60s girlfriend Suze Rotolo and any number of his songs of 1964-66 are said to be ‘about’ either Joan Baez or Sara Lownds, who he secretly married in November 1965. Dylan, who guards his private life very carefully and never likes his songs to be ‘pinned down’ to particular meanings, has always steadfastly avoided admitting that any of his songs are written ‘for’ particular individuals.

Even the song cycle Blood on the Tracks, although written at the time when his marriage to Sara was clearly in trouble, cloaks its messages in ambiguity.In Chronicles he claims (rather dubiously) that the album was not about his marriage at all but is based on a collection of Chekov’s short stories. It is hardly surprising that an artist like Dylan, whose every written lyric or public pronouncement gets analysed in great detail, should seek to conceal actual details of his private life. Also, songs like Boots of Spanish Leather, while they may have been ‘inspired’ by a particular woman, do not mention her by name and can thus be applied by listeners to their own relationships and experiences. Yet when Dylan released Sara, the last track on 1976’s Desire, for the first (and only) time he appeared to be leaving listeners in no doubt as to whom the song was about. His subsequent claim in an interview that the song was addressed to the Biblical Sara, the wife of Jewish patriarch Abraham, was extremely unconvincing, to say the least. The song was, perhaps because of its intensely personal nature, never performed by Dylan after 1976. Apart from Barb Jungr’s jazzy take, it has also attracted few covers, many of which have been in Spanish or Italian language versions.

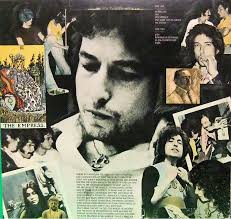

BOB AND SARA IN WOODSTOCK, 1968

Sara is clearly an autobiographical song. It is a highly moving and desperate plea, which focuses on the happy earlier days of their relationship when their children were very small. There is no mention of marital strife. But the song is so obviously about Dylan’s own life that the lack of subterfuge or ambiguity is striking in itself. Desire is an album of songs that are conceived of as short ‘movies’ in various genres. Romance in Durango, One More Cup of Coffee and Isis are all Mexican-themed ‘Westerns’. Joey is a rather mawkish ‘Mafia flick’. Hurricane is a gritty, anti-racist ‘social conscience’ story, whereas Mozambique and Black Diamond Bay are comic tales set in ‘exotic’ locations.In this context Sara can be seen as a highly romanticised ‘biopic’ consisting of several stylised blissfully happy scenes from an imagined past. It is unashamedly nostalgic and sentimental and isquite clearly designed to ‘pull on the heart strings’ of Dylan’s estranged wife, so that she will forgive him and come back to him.

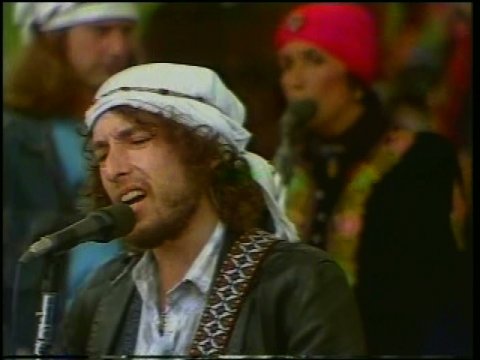

The song also differs from most of Dylan’s work in that it is not difficult to interpret. The six verses consist of sepia-tinted scenes of happy occasions from the past, presented to us in the form of clear and evocative images. Each verse is followed by a variable plaintive chorus, in which Bob idealises Sara and pleads for her to return to him. Dylan enunciates with great clarity, delivering a truly passionate performance. His use of the harmonica is especially effective. The overall tone of the song, however, is one of deep and profound sadness. According to Dylan’s biographer Howard Sounes, Dylan actually asked Sara to be present at the recording sessionwhen he unleashed the song for the first time. The couple did reunite and Sara became part of the upcoming Rolling Thunder revue, playing the leading role of Clara in Renaldo and Clara, Dylan’s experimental ‘arthouse’ film of the tour. But their reconciliation did not last and a very messy divorce followed. Despite Dylan’s heartfelt appeals to Sara, the prevailing mood of the song suggests that, deep down; he already knew that their marriage was doomed. Whatever transgressions he committed (which certainly, in real life, included him having affairs with other women) are never outlined in any detail. The song has the air of a tragedy. The fact that Dylan, always good at ‘keeping things vague’ (as Joan Baez put it in Diamonds and Rust), has actually exposed elements of his real life adds to the poignancy of the song. His tone of mournful regret makes it a genuine tearjerker. But it is not always clear that he considers himself to be responsible for the problems in the marriage.

BOB AND SARA ARRIVING IN ENGLAND, 1969

We begin with a simple but evocative description of an emotional memory. Dylan is lying on a dune, at a time when …the children were babies and played on the beach… Sara appears behind him …You were always so close… he sings …and still within reach…In the first chorus he asks her …Whatever made you want to change your mind?…This is of course a rhetorical question, the answer to which he is not going to supply. In a nod to Sara’s well known interest in Zen Buddhism which Dylan had previously paid tribute to in Love Minus Zero/ No Limit, he calls her …so easy to look at, so hard to define…Dylan then draws on his memory of their childrenplaying on the beach. The descriptions are simple but highly emotive: …I can still see them playing with their pails in the sand/ They run to the water, their buckets to fill… Then we ‘zoom in’ for a ‘close up’: …I can still see the shells falling out of their hands/ As they follow each other back up the hill…The image of the shells that the children have gathered falling back into the sand is especially affecting, as if the children are already in the process of losing something but – in their innocence – are basically unaware that this is happening. Dylan tries to distract Sara from this troubling image by repeating her name over and over in the chorus, idealising her as a …sweet virgin angel…and a …radiant jewel, mystical wife… But inevitably it is the resonant image of the children playing, with its association with the happiness of the family that is now broken, that sticks in our minds – and perhaps Sara’s – the most.

In the third verse, Dylan continues to produce more evocative ‘flashbacks’ showing scenes of marital bliss. But now the images of the past come thick and fast but are more broken up, as he appears to search his memory in desperation …Sleeping in the woods by a fire in the night… is followed by…Drinking white rum in a Portugal bar…Then we return to more sentimentalised images of the children, who are …playing leapfrog and hearing about Snow White… before we cut to a ‘still’ of Sara …in the market place at Savannah-la-Mar… (a resort in Jamaica). In the live performances of the song, lines two to five are changed …You fought for my soul… he sings …and went up against the odds…This isfollowed by a rare piece of self-deprecation: …I was too young to know you were doing it right… he tells her, before eulogising her in no uncertain terms …But you did it with strength that belonged to the gods… The new lines may lack the pathos of what came before, but they do supply some practical praise for Sara – in particular, for saving him from the self-destructiveness of his lifestyle – which had previously been absent. The reference to ‘gods’ also credits Sara with divine powers, a theme which will continue throughout the song. The next chorus, with the apparently rather prosaic sentiments of: …Sara, Sara, it’s all so clear I could never forget/ Sara, Sara, loving you is one thing I could never regret… is double-edged. He admits that he will never regret loving her, but we are left wondering about so much that is unsaid here and the many ‘regrets’ that he does not have the courage to own up to.

The fourth verse provides the biggest shock for Dylan fans. The first line: …I can still hear the sound of those Methodist bells… is highly evocative, if somewhat portentous. Then we hear that: …I’d taken the cure, and I’d just gotten through…Here Dylan appears (at least on the surface) to be being disarmingly honest about his personal life. The line suggests that he had been a drug addict, unless he is referring to some unknown illness (possibly a sexually transmitted disease). But the impact of this is somewhat buried by the next revelation: …Stayin’ up for days in the Chelsea Hotel/ Writing ‘Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands’ for you… Here, for the first and only time, Dylan refers within a song to the composition of one of his songs – and a major song at that. All this, however, may be mere subterfuge, as according to the musicians that played on Blonde on Blonde, Sad Eyed Lady was composed in the studio while he was working on the album. And although that famous epic ballad contains several knowing references to Sara (‘Lowlands’ is often thought to be a play on ‘Lownds’and the reference to the ‘magazine husband’seems to refer Hans Lownds, her first husband who was a journalist) it is debatable whether the song is entirely ‘about’ her or whether the ‘Sad Eyed Lady’ is a composite of all Dylan’s lovers(or may even refer to Dylan himself).

None of this may be terribly surprising for ‘Dylan watchers’. We expect him to present a colourful and highly imagined version of his past history, as he did when he first emerged as a folk singer, claiming to have left home as a young teenager and spending several years working in traveling carnivals. In Chronicles many of his recalled memories appear to be, to say the least, exaggerated. But in making such a statement about the composition of one of his most ‘legendary’ songs, Dylan appears to be truly ‘laying himself on the line’ by publically revealing the sort of detail that normally he keeps very close to his chest. This certainly impressed Dylan’s fans, although whether Sara herself truly believed it is perhaps another matter. In the chorus that follows Dylan reassures her that …Wherever we travel we’re never apart… suggesting that he is preparing for a future in which they will really be separated.

THE BEACH AT LILY POND LANE

Dylan continues the process of mythologisation: …How did I meet you…he asks. At first he tells usthat …I don’t know… But this is merely another rhetorical trick. He then declares proudly: …A messenger sent me in a tropical storm… which sounds like he is referring to Mercury, the Roman Messenger of the Gods. This followed by another idealised image of Sara: …You were there in the winter, moonlight on the snow/ And on Lily Pond Lane when the weather was warm… Lily Pond Lane is the location of a beach at East Hampton, on Long Island, in New York State. Presumably this is the location of the beach that features in the song. Dylan now seems be suggesting that their union was some kind of mystical process, decreed by ‘the gods’. This is amplified by the beautifully alliterative first line in the next chorus: …Sara, oh Sara/ Scorpio sphinx in a calico dress… another tribute to her ‘mystical’ and apparently inscrutable personality. Then, having built up his wife to a God-like status he proceeds to deliver, for the first time, some kind of confession of his own responsibility for what has happened: …You must forgive me my unworthiness…

ANGELICA KAUFMANN: NYMPH DRAWING HER BOW ON A YOUTH

After a poignant harmonica break, the final verse begins with the heartbreakingly elegiac: …Now the beach is deserted except for some kelp/ And a piece of an old ship that lies on the shore… The empty beach and the broken ship both seem to symbolise the state of their marriage. This is followed by more praise for Sara: …You always responded when I needed your help/ You gave me map and a key to your door… Sara is further ‘deified’ as a ..glamorous nymph with an arrow and bow… This appears to a reference to a famous painting by the eighteenth century Swiss Artist Angelica Kauffman in which a nymph aims her bow at a shepherd, using one of Cupid’s arrows. Dylan clearly hopes that Sara will magically revitalise their relationship by shooting one of these ‘love arrows’.

It seems unlikely, however, that this will actually happen. Despite Dylan’s pleas, the magic in the relationship is surely over. The song, which concludes with more plaintive harmonica, is tragic rather than uplifting. We get a very strong sense that Dylan is not really tackling the problems in the marriage. In fact, he is avoiding them, and not admitting any culpability on his own part, with the exception of his own ‘unworthiness’; the confession of which is perhaps brave but decidedly vague. It seems that the really tragic elements of what has occurred within the marriage are unspoken. Sadly, passionately metaphysical poetry and begging for forgiveness will not wish them away. Dylan’s songs are often misunderstood by those who do not grasp the fact that so much of what he sings is expressed through the voice of a narrator, who himself is a fictional character. So the sentiments expressed in the songs are not necessarily Dylan’s own. In Sara, a song which appears at first to – for once, put away these ‘masks’, it finally appears that he is still singing through the voice of a narrator -in this case, a fictional character called ‘Bob Dylan’, who here addresses the woman he as wronged as a ‘goddess’. In doing so, be creates the sense of hopeless longing, mixed with tearful nostalgia, which gives the song its great emotional power.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mqJ3mMMdG-c

Leave a Reply