Hi folks! Special 50th Anniversary deep dive into Bob Dylan’s first Hollywood role…

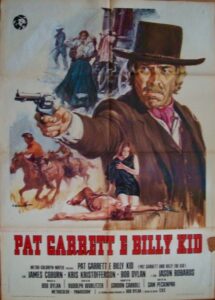

Pat Garrett….

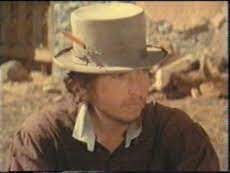

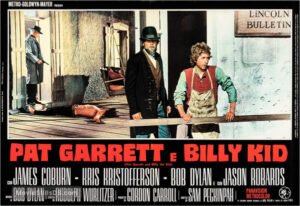

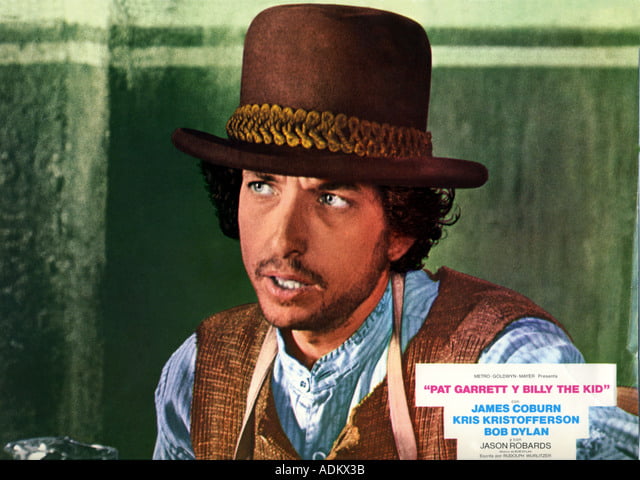

The little guy in the in brown overalls and a stove pipe hat is sitting in the corner of the saloon staring rather vacantly into space. We cut to the big bad lawman, who has just been given a shave. He’s a pretty scary guy. He’s fast on the draw and takes no prisoners. He squints and asks the little guy, who so far hasn’t said a word, a searching question. You don’t mess with Pat Garrett. Give an answer he doesn’t like and that six shooter will be out of the holster faster than you can say ‘draw’.

Garrett isn’t one to mince his words. …Who are you?.. he enquires.

The little guy stares down at the table in front of him for a moment. We might be wondering if he has a weapon concealed under there and whether he fancies trying to make his name by knocking off the former outlaw. But he merely replies “That’s a good question” and takes a slug of rot gut.

The next time we see the little guy he emerges from a doorway and surveys the dead bodies lying in the street of the Western town and gives a crooked smile. Across the way, the even deadlier Billy the Kid is cleaning his gun, having mercilessly dispatched several renegades. This situation is even more dangerous. Billy smiles as he kills. In fact he is smiling through most of the movie. It’s crucial that the little guy doesn’t say the wrong thing. Otherwise he’ll join the pile of corpses. But instead he smiles broadly, like maybe it’s Christmas or his birthday. One of Billy’s menacing honchos eyes him up suspiciously. He asks the same question Garrett posed earlier.

The little guy merely replies …Alias…

…Alias what?…

…Alias anything you please…

Pat Garrett…

This is not, of course, the kind of scene that would appear in an old style Western. John Wayne would no doubt have plugged him just for being such a brat. But Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid is a revisionist Western, full of gore, splatter and half naked whores. The era of American triumphalism is over. The war in Vietnam has been ignominiously lost and the man in the White House is desperately trying to cover up the scandal that will soon bring him down. The cowboys in this film are long haired and filthy, like they’ve just staggered out of Woodstock, or perhaps Altamont. They shoot each other without emotion, like they’re just doing an every day job of work. And then there is the character of Alias…

KRIS KRISTOFFERSON AND BOB DYLAN

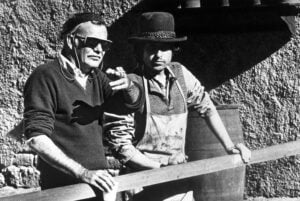

Pat Garrett provides Bob Dylan with his first real entry into Hollywood. He is treading the same path as Elvis and Ricky Nelson. But this is 1973, not 1963. And the director is the whiskey swilling Sam Peckinpah, notorious for his ultra-bloody gun slinging epics like The Wild Bunch and Ride the High Country, not John Ford. Kris Kristofferson, also a country rock singer and brilliant song writer (who seven years earlier had been employed in CBS studios in Nashville as a janitor and tea boy during the Blonde on Blonde sessions), is a highly accomplished actor who already has a couple of big movies under his belt and would go on to star in around seventy more. His nemesis and former outlaw compatriot Pat Garrett is played by the taciturn, menacing James Coburn. The movie charts how Garrett tracks down and finally slays the smiling Billy, not in an old fashioned ‘fair’ shoot out but in cold blood. In between these two titans of cinema, Dylan, whose acting style here can best be described as ‘eccentric’, shuffles around uncertainly. He never picks up a guitar or sings but we see him lassoing turkeys and quite accurately throwing as knife into the guts of one of the bad guys. It might be said, however, that in this film all the main protagonists are bad guys. Rather like in Vietnam…

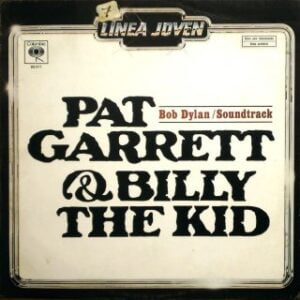

Originally Dylan had been employed just to provide the soundtrack but was eventually given a small part. He was, however, credited just below the two main stars. Obviously his name on the billboards helped attract the young anti-establishment audience in the post-Easy Rider cinema landscape. Dylan’s role was added to the film by Rudy Wurlitzer, a screen writer with avant garde tendencies who also wrote the off beat road movie Two Lane Blacktop, which started two more rock stars, James Taylor and Dennis Wilson. Wurlitzer clearly understood something about Dylan’s enigmatic persona and created the character of Alias with that in mind. Despite his lack of thespian credentials Dylan turns out to be an important presence in the movie, giving it a slightly bizarre comic edge. His major scene occurs when Garrett, to keep him out of the way, orders him to read out the names of stacked up tins. While the action of the scene continues, we hear Alias in the background, reading out the names of a variety of beans in Dylan’s characteristic mid Western drawl.

BEANS…. BEANS….. BEANS…

Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid is, like The Wild Bunch, an ‘elegiac’ Western. It is set in the early twentieth century, as the ‘old West’ is dying. Like the equally violent ‘spaghetti Westerns’ of Sergio Leone (also mainly set in Mexico), it is bereft of any heroism or conventional moral message. Yet it has a few moments which are genuinely moving, most notably the death scene of Sherriff Colin Baker, played by the iconic Western actor Slim Pickens. The scene is accompanied by Dylan’s most elegiac composition Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door, which later became one of his most well known songs. The song is clearly written to accompany the scene. …Mama take this badge offa me/ I can’t use it any more… Dylan sings as the dying sheriff sits by a lake, clutching his stomach …It’s getting dark, too dark to see/ I feel like I’m knockin’ on heaven’s door… The second and last verse repeats the pattern with a little variation: Mama, put my guns in the ground/ I can’t shoot them anymore/ That long black cloud is comin’ down/I feel like I’m knockin’ on heaven’s door…. But it is the chorus, in which Dylan (accompanied by three female backing vocalists) merely repeats …knock, knock, knockin’ on heaven’s door… four times, along with the song’s gloriously aching melody, which makes it so distinctive, catchy and infectious. Despite the minimal lyrics, the song sums up the message of the movie with great eloquence. Slim Pickens, veteran of more than fifty Westerns, represents the ‘old West’ which itself is dying, along with the ‘all American’ values it represents.

SLIM PICKENS’ DEATH SCENE

The use of Dylan to compose the film’s soundtrack could be considered another signifier of its status as a revisionist Western. Dylan, however, is an aficionado of Westerns and had clearly studied Western soundtracks before composing the music. He largely sticks to the ‘country rock’ sound that he had been associated with since Nashville Skyline. Most of the soundtrack (as well as the accompanying album) consists of instrumentals, which are played by a studio band featuring Dylan, Roger McGuinn, Bruce Langhorne and Carol Hunter on ‘massed’ acoustic guitars, Booker T. Jones on bass and Jim Keltner on drums. The contemplative Main Title Theme which opens the album and is featured early in the film sets the tone, picking up a rhythm which approximates the sound of horses trotting. Most of the other instrumentals (apart from the fiddle-dominated Turkey Chase) are variants on the main theme, which also has some resemblance to the film’s ‘narrative song’ Billy. This is in keeping with the use of recurring themes as cinematic leitmotifs, often signifying the entrances and exits of particular characters. Overall the music is leisurely and gentle and conveys a strong feeling of reflective sadness, in contrast to the violent action. This fits well with the film, which mingles the kind of realistic violence rarely seen in old Westerns with much pathos as the certainty of the old values dies away.

SAM PECKINPAH AND BOB DYLAN ON THE SET OF PAT GARRETT AND BILLY THE KID

Billy, which appears in several versions in the film and on the soundtrack, is written in the tradition of Western narrative songs such as the title song to John Ford’s The Searchers (1956) sung by the Sons of the Pioneers, Do Not Forsake Me, Oh My Darlin’ by Tex Ritter in High Noon and My Rifle, My Pony and Me, which is performed by Dean Martin and Ricky Nelson in Howard Hawks’ Rio Bravo (1959). Such songs often give the audience another slant on the story and insights into the character. Billy is also influenced by country ballads like Marty Robbins’ El Paso and Streets of Laredo , Johnny Cash’s Don’t Take Your Guns to Town and the traditional Ballad of Billy the Kid. Dylan’s song is sympathetic towards its title character. It has nine verses, in which the first three lines always rhyme and final lines containing Billy’s name, which rhyme intermittently. The song describes how Billy is being hunted by …guns across the river… and pursued by mercenary bounty hunters who …don’t like you to be so free… and want to send him …up to Boot Hill… (a location which is traditionally used in Westerns to signify death). We are told that …There’s mirrors inside the minds of crazy faces… while …some trigger happy fool… is always ready to take a pop at him. Billy himself spends his time …Playing around with some sweet senorita… as he does in the film, where he consorts with a number of Mexican whores. Finally Billy is given a kind of ceremonial send off as we hear that …Gypsy queens will play your grand finale…

Billy the Kid (William Bonney) was a real historical figure; an iconic gunslinger and outlaw with many kills to his name. As with other cowboy heroes such as Wyatt Earp, Doc Holiday, Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid, he became famous through comic books and later movies. The real Billy died some thirty years before the action of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. He was only twenty one when he met his end, whereas Kristofferson was 36 when the film was made. Billy features in many films in which little regard was paid to his real exploits. Like the other Western heroes his life was soon mythologised. In Peckinpah’s film, despite his cold ruthlessness while committing murders, he is a sympathetic figure who is portrayed as being hounded by the authorities. Dylan’s song reflects this. The previous friendship with outlaw turned lawman Garrett is another largely fictional construct in a film which focuses on the theme of betrayal. Dylan himself, influenced by Woody Guthrie’s romanticisation of an outlaw in Pretty Boy Floyd seems to have identified with Billy. At this point in his career he was nearing the end of his seven year retreat from the public eye. Like the fictional outlaw, he felt he was being ‘hounded’ and, indeed, mythologised by fans, critics and commentators. This is reflected in one of the verse endings …Billy, they don’t like you to be so free…

BOB DYLAN AS ‘ALIAS’

Although Dylan’s soundtrack album is generally regarded as a minor entry in his canon, the songs did have a considerable afterlife. In the 2000s Billy became a favourite with Americana performers such as Gillian Welch. Two outtakes from the sessions which were not used in the film, Rock Me Mama and Sweet Amarillo, were taken up and adapted by the Americana band Old Crow Medicine Show and became major hits in the same period. Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door became a true rock standard, with notable covers in a number of genres. Eric Clapton released a reggae arrangement, while Guns and Roses had a major global hit with a rock/metal version. It was also recorded by Roger McGuinn, Bryan Ferry, The Grateful Dead, Warren Zevon and many others. Fairport Convention, with Sandy Denny on vocals, produced a mesmeric live reading.

Dylan himself began playing an extended rock version on the 1974 tour. Between then and 2003 he took the song through many different iterations and arrangements, sometimes adding extra lyrics to flesh the song out and frequently adding the line …Just like so many times before… to the chorus, almost as a self mocking reference to its status as such a hugely commercial song. Its success may well have provided some of the impetus for Dylan’s return to the stage in 1974 and it demonstrated to the world that he was capable of composing songs that, even if they eschewed his usual penchant for extended lines, verses and complex poetic symbolism, could touch the hearts of listeners in ways that could not always be easily defined.

Leave a Reply