New Morning 2…

The two songs that complete Side One of the album – Winterlude and If Dogs Run Free – are also comic pieces. They take Dylan into new musical territory. Although their musical templates are quite different to the rest of the album, they maintain the dream-like ambience. Winterlude is a country-style ‘skating waltz’ which piles cliché on cliché in an evocation of an idyllic snowbound scene and which could be said to anticipate 2009’s Christmas in the Heart album. It is a kind of love song to the winter itself, refracted through an idealised version of Dylan’s own childhood in the cold North Country. It also marks the first signs of Dylan’s fascination with the American sentimental musical tradition, which will influence much of his output in the 1980s and eventually lead to the ‘Sinatra trilogy’ of the 2010s. The song has some resemblance to Presley’s ultra-syrupy Crying in the Chapel, while its wintry imagery conjures up scenes from romantic Astaire-Rogers movies such as Swing Time (1936) in which the legendary couple’s spectacular dance moves are set against blizzards of fake snow or Shall We Dance (1937), where the pair cavort in roller skates on a skating rink in Central Park.

ASTAIRE AND ROGERS IN ‘SWING TIME’

New Morning… Snowflakes…

With his tongue very firmly in his cheek, and using a vocal delivery similar to the ‘softened’ Nashville Skyline tone, Dylan depicts a ‘winter wonderland’ while confessing his love to a girl called ‘Winterlude’, who he refers to as …darlin…, …my little apple… and then …my little daisy… cranking up the corniness as he rhymes these terms of endearment with …no quarrelin’… , …chapel… and …lazy… He clearly delights in this feast of self parodic humour. Lines like …you’re the one I adore/ Come over here and give me more… and the way he refers to the girl as …the angel beside me… add to this effect. In the second and third verses the narrator celebrates the snowy scene, as he implores his love to …come out when the skating rink glistens… while …the snow is so cold, but our love can be bold…

Later …the moonlight reflects from the window/ While the snowflakes they cover the sand… All this is observed from the comfort of home, where the lovers sit by a log fire. There is certainly a sense here that Dylan (as on Self Portrait) is mocking his own public image and taunting his fans. Winterlude presents another dreamscape in which the narrator drifts back in his mind to his childhood. It presents his rural retreat as cosy and Disneyfied. But as both the narrator and his sceptical audience must both know, it may not be long before the ‘snow white’ scene will melt away.

If Dogs Run Free is a jokey ‘philosophical’ spoken piece and an affectionate parody of the 1950s jazz and poetry scene beloved of the Beat Poets. It features Al Kooper knocking out some jazzy riffs on the piano and Maeretha Stewart supplying some delirious scat singing in between the verses. The lyrics consist of a rather flippant discourse on human freedom, as if Dylan is asserting his right to produce art that reflects his current situation rather than – as many of his fans and quite a few music journalists would like – continually repeating himself by reproducing the ‘protests of his early period or the songs full of ‘chains of flashing images’ of his 65-66 output. The first take of the song (which is included on Another Self Portrait) is backed up by acoustic guitars, bass and drums. But the jazzy version fits much better with the Beat-style lyrics, which give us the first of the song’s rather odd and fanciful metaphors…If dogs run free then why not we/ Across the swooping plain… Later we get the …swamp of time… and two ‘symphonies’, one of …two mules, trains and rain… and later …a symphony and tapestry of rhyme… The narrator declares the wish to be …in harmony with the cosmic sea… He assures us that …true love can make a blade of grass stand up straight and tall…

AL KOOPER

New Morning -rhyming

Dylan appears to be choosing some of these expressions for their ‘cool’ sound and internal rhyme rather than any explicit meaning. But the use of musical imagery and what sound like improvised lyrics indicate that the song, despite being almost a mockery of ‘serious’ poetry, expresses a genuine desire by the singer to be free from musical and lyrical constraints. The way it switches musical genres after Winterlude is a defiant demonstration of the singer’s intention to explore both new musical areas and new ways of expressing himself. The jazzy inflections again return us to the music of Dylan’s childhood, taking us further into the album’s retrospective dream world.

New Morning includes several rather dreamy love songs, indicating that it is the overwhelming affection he feels for a particular woman that keeps the narrator happy in his rural retreat. One More Weekend is a joyful if rather inconsequential twelve bar blues in which the narrator expresses his lustful desire to spend ‘one more weekend’ with the object of his desire. The fact that he is only asking for such a brief liaison indicates that rather than confessing true love, he is playing the part of a seducer, announcing that …You’re the sweetest gone mama this boy’s ever gonna get… He urges her to …leave all the children home… so they can be alone (for obvious reasons). He promises her a weekend of lustful fun in which they will be …flyin’ over the ocean… Bigging himself up, he declares that he is …slippin’ and slidin’… (a reference to a sexually provocative Little Richard song) …like a weasel on the run… Later he tells her that he is …like a rabbit in the wood… and tells her that …like a needle in a haystack, I’m gonna find you yet… referring to the place where countryside lovers traditionally explore their passion. The song is another parodic exercise, with Dylan indulging in typically suggestive blues imagery, and cannot be said to be anything but a few minutes of frothy fun.

The Man in Me, in contrast, is a skilfully constructed pop song in which the narrator tells us in all sincerity that the woman in his life has genuinely changed him. It features cooing female vocalists and Dylan very uncharacteristically filling the musical spaces with ‘la las’. The song carries a genuine emotional strength as well as being eminently hummable. It later found fame illustrating a dream sequence in the Coen Brothers’ comic masterpiece The Big Lebowski (1998) featuring Jeff Bridges’ ultimate slacker ‘The Dude’ floating miraculously through the air. The song is influenced by the minimalism of the lyricists of the ‘Great American songbook’. Its wistful supplications resemble those in ‘show tunes’ such as Dooley Wilson’s As Time Goes By or You Go to My Head by Haven Gillespie and Fred Coots (both later covered by Dylan on 2017’s Triplicate) and Willie Nelson’s Crazy (immortalised by Patsy Cline) in which the narrators humble themselves in awe of their lovers.

The recording benefits from a clever and attractive musical arrangement with organ and piano again intersecting. Dylan’s vocal, especially on the ‘la las’ is a little strained, which adds a certain level of pathos. The lyrics are fairly minimal, with half of the three short verses consisting of the chorus with its simple internal rhyme: …Takes a woman like you/ To get through to the man in me… There is a slight variation in the second verse: …Takes a woman like your kind/ To find the man in me… Dylan had rarely displayed such meekness in the past. Most of his early ‘love songs’, like Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right, Mama You Been On My Mind or One Too Many Mornings had depicted his narrators as ‘moving on’ from failed relationships. Later songs like Like a Rolling Stone, One of Us Must Know, She’s Your Lover Now or Just Like a Woman had been especially scathing towards the women being addressed. An exception was 1963’s Tomorrow is a Long Time, with its declaration of pure love linked to pastoral imagery. It is not surprising that this last song, which Dylan had never recorded despite it being covered by many artists including Elvis Presley, was reworked in the New Morning sessions for possible inclusion on the album.

The remaining lines in the first verse consist of the self effacing confession that …The man in me will do nearly any task/ But as for compensation, there’s a little he will ask… In verse two we hear that …Storm clouds are raging all around my door/ I think to myself I can’t take it any more… a simple metaphor reminiscent of the standard Stormy Weather, written by Harold Arlen and Ted Koehler. In the third verse the narrator becomes even more self deprecating: …The man in me will hide sometimes to keep from being seen/ But that’s just because he doesn’t want to turn into some machine… The song is so effective because the narrator sounds so genuinely determined to hold onto his basic humanity. We will never know whether his pleas to the woman will produce a response. Indeed, we find out nothing about the woman herself. The song is concerned entirely with the man’s inner struggle with his own identity.

The Man in Me demonstrates that Dylan himself felt that he needed to reconnect with some of the basic simplicities of life in order to regain inspiration, rather than churning out ‘typical Dylan’ songs with machine-like efficiency. By adopting a hesitant tone he conveys his vulnerability very movingly. But the high point of the song, partly because of how much it contrasts with the verses, is the ecstatic thrill he delivers in the bridge section in which he cries …But oh, what a wonderful feeling/ Just to know that you are near/ It sets my heart a-reeling/ From my toes up to my ears… In these lines, in which the music builds in great intensity, the narrator lets the reticence of the verses go. The song can be seen as a plea to Dylan’s audience to keep faith in him, despite the apparently strange turn his career has taken. These lines allow him a measured release of regretful emotion at having to ‘hide sometimes from being seen’. They express a longing to return to the public arena, despite the ‘storm clouds’ gathering outside. Yet for the moment we are left in no doubt that he will, at least for now, remain ‘in hiding’.

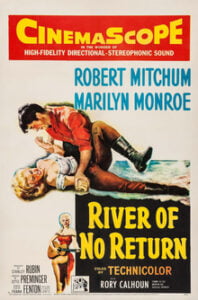

Between the 1978 tour and 2011, the song featured regularly in Dylan’s set lists. The 1978 version of the song – first developed during the rehearsals at Rundown Studios in LA in late 1977 – features variant lyrics which shift the tone of the song considerably. The ‘storm clouds’ line is replaced by the decidedly more extreme …Lost on the river of no return… (a reference to Otto Preminger’s 1954 western starring Robert Mitchum and Marilyn Monroe). The song now contains a disarmingly honest confession of infidelity: …I know you got a husband, and that’s a fact/ But, if you don’t wanna turn me loose, please cover my tracks… Whether the insertion of these lines had any relevance to Dylan’s personal situation at the time is unknown. But in later years the original lyrics returned. The song has inspired a plethora of cover versions, including a striking reggae version by Matumbi (1976) which was the model for Joe Cocker’s soulful reading of the same year. Since the release of The Big Lebowski, it has become something of an ‘Americana standard’ with covers by Cracker, Jason Isbell, Emma Swift and others.

The most cheerful and heart warming song on the album is undoubtedly the title track, with its rousing repeated chorus: …So happy just to see you smile (later …to be alive…) underneath that sky of blue/ On this New Morning (repeated) with you… As with The Man in Me the other lyrics are minimal. Here they paint a rosy and nostalgic picture of the rural idyll. The infectious rhythm of the song – propelled by Russ Kunkel’s spirited drumming – suggests that the lovers are driving down a rather bumpy country road in an old jalopy in some dreamlike version of the past …Can’t you hear that rooster crowin’ / Rabbit runnin’ down across the road/ Underneath the bridge where the water flowed through… It is as they are driving through a picture postcard. In many ways the song recalls the tearful joyousness of Louis Armstrong’s monumental recent hit (What a) Wonderful World.

HIBBING

All three verses begin with a question, which draws the listener into this warm and reassuring scene. …Can’t you hear that rooster crowin’?… is followed by …Can’t you hear that motor turnin’ ?… and …Can’t you feel that sun-a-shinin’… Each one involves the listener viscerally in the song. …Automobile coming into style… suggests an early twentieth century setting. The bumpy drive continues: …Coming down the road for a country mile or two… We see a ..groundhog running by a country stream… Dylan declares exuberantly …This must be the day that all of my dreams come true… It is easy to see why this is the title track. In no other song does Dylan convey such pure joy in such an unequivocal way. Here, in a nutshell, is the essence of his pastoral retreat, with all the elements painted in suitably tasteful shades, like one of Constable’s intricate landscapes.

If Not For You, which opens the album, is another ‘pure’ love song. It could almost be described as an exercise in simplicity, with Dylan attempting to produce the most ‘stripped down’ use of language possible. The song has been covered widely, with versions by George Harrison, Olivia Newton John (who scored a top ten hit with the song in the UK), Bryan Ferry, Richie Havens, Barb Jungr and many others. Dylan has performed the song around 100 times in concert. Although many of his live versions are enhanced by varied instruments, he has never changed the lyrics. He also retains the recorded version’s jaunty tone throughout. The song works just as well, however, as a slow ballad, as Dylan demonstrates on the violin-led version that appears on Another Self Portrait.

The song contains four verses, one of which is repeated. It stays strictly within its ABBAA rhyme scheme. There is no chorus or bridge but the title line is repeated at the beginning and end of each verse. It begins in a fairly nondescript and static way, with the narrator trapped inside a room: ...If not for you/ Babe I couldn’t find the door/ Couldn’t even see the floor/If not for you… Then we hear him eagerly anticipating the ‘new morning’ to come. He tells us that without her presence …I’d lie awake all night/ Wait for the morning light/ To come shining through/ But it would not be new/If not for you… In the third verse we then step outside. The narrator tells us that …If not for you/ My sky would fall/ Rain would gather too… The phrase ‘my sky would fall’, apart from conjuring memories of the nursery rhyme character Chicken Little, strongly suggests that this ‘sky of blue’ – the dream landscape that is created on the album – could all collapse without the lover who makes this all possible. The use of the word ‘gather’ (normally used to describe clouds rather than the rain that comes out of them) is an interesting use of pathetic fallacy, as if the rain is waiting to fall if the lover were to absent herself. To emphasise just how much she is ‘holding up the sky’, he cries: …Without your love I’d be nowhere at all/ I’d be lost if not for you…

There is so much emphasis in the song on his dependence on her that the song that some have identified it as actually addressing God rather than a woman. The chief evidence for this comes in the last verse, where Dylan declares …If not for you/ Winter would have no spring/ Couldn’t hear a robin sing/ Anyway it wouldn’t ring true/ If not for you… Certainly one might argue that the female love object is the creator and upholder of New Morning’s pastoral paradise. But, given that she is addressed earlier as ‘babe’, it is stretching a point to identify her as a deity. It is certainly true, however, that If Not For You is a song of faith. But that faith is dependent on the good will of another human being. Without her presence, the entire edifice could clearly come crashing down. Thus the song symbolises both the hope and fear that are interwoven throughout the songs of the album. Dylan’s use of a deliberately minimal syntax here positions him as a humble supplicant. Whereas once – in the love songs of Blonde on Blonde – he presented himself as a humorously detached and often cynical participant in multiple love affairs, here he presents is a simple guy, a ‘one man woman’, who is so in love that without her his world will collapse. His sky will fall in. Winter would not be succeeded by spring. By positioning himself like this, and by utilising the simplest language possible, Dylan celebrates the directness of such devotional love with humble grace and precision. But what gives the song its inner power is that the narrator is in fact a fragile being who freely admits his dependence on the woman.

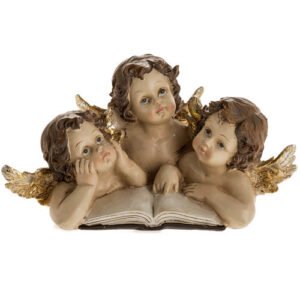

New Morning seems to be bound together by the idea that simple faith in love can bring redemption. Dylan invests this concept with a dreamy reverence throughout the album, inviting us rather shyly into his ‘secret world’. In the last two tracks, however, he moves, perhaps rather tentatively, into more conventionally religious areas. Three Angels is a spoken word poem which is the most dreamlike of all the tracks on the album. It takes us back to the idealised childhood Christmas of Winterlude. The music – which is dominated by washes of ‘dreamy’ organ – resembles the backing for spoken word ‘confessionals’; a popular sub-genre of country music in which the singers delivered moral lessons to their audience. Examples are Wink Martindale’s Deck of Cards and the sides that Hank Williams recorded as ‘Luke the Drifter’. Dylan uses this form knowingly, but with his tongue firmly in his cheek.

The first lines: …Three angels up above the street, each one playing a horn… sound like the beginning of a ‘cornball’ religious homily. But we hear that the angels are …Dressed in green robes with wings that stick out… and that …They’ve been there since Christmas morn… which suggests that they are actually cheap shop made dummies put there to publicise the store’s Christmas sales. This may be one of Dylan’s putdowns of the cheapening of religious icons, as in the line …flesh colored Christs that glow in the dark…from It’s Alright Ma, I’m Only Bleeding. We are then presented with a series of surreal characters and situations: …The wildest cat from Montana passes by in a flash… presumably refers to a ‘beatnik’ character straight out of On the Road. There’s a splash of colour …a lady in a bright orange dress… a lorry carrying goods and …a Tenth Avenue bus going West… We may assume that we are in New York, as this suggests, but in that case the bus is going in the wrong direction. The narrative becomes weirder, telling us that …the dogs and pigeons fly up and they flutter around… Presumably the dogs are flying with the pigeons! Then, completely randomly …a man with a badge skips by… We also see …three fellas crawling on their way to work… Then ‘Bob the Drifter’ interjects, commenting that …Nobody stops to ask why…

Dylan thus paints a picture of a weirdly twisted world. Yet it is one in which the inhabitants merely carry on acting normally. A bakery truck is then seen parking under the spot where …the angels stand high on their poles… The driver looks out of the window …trying to find one face/ In this concrete world full of souls… It is as if the entire scene is a rather fantastical cartoonish representation of the ‘concrete’ or material world, in which most people ignore the inherent strangeness that is all around them. What is missing, it seems, is a real spiritual dimension. This world is hollow. Finally Dylan tells us that these ‘fake angels’ do continue to play their horns – suggesting, perhaps that this bizarre world will soon come to an end in some kind of revelatory judgement. As the song ends we seem to be miraculously gliding up to the angels’ level to share the observation that …the whole earth in progression seems to pass by… Then Dylan the Moralist interjects …But does anyone hear the music they play? Does anyone even try?….

This final question appears to sum up the entire existence of the ideal dream world depicted in the album. It suggests that fantastical events are occurring just beneath the surface of the everyday world. In that ‘hidden’ realm, ordinary life is illuminated by a kind of divine light which creates a bucolic paradise. The ‘music’ which the angels play is the soundtrack to this paradisiacal state, but Dylan suggests here that most people are oblivious to it. This suggests that humans can create a kind of ‘heaven on earth’ if only they can become more aware of the wonders of existence itself. Yet a strong doubt is expressed that anything will really change. The ‘angels’ are, after all, fake human creations presumably fitted with repeating tapes in order to draw shoppers into the commercial world of Christmas shopping. Thus the song, and the whole album, examines how human being can balance materialism with spirituality. Three Angels takes a rather left-field, skewed look at this fundamental human dilemma and concludes that, although the narrator of these songs may have entered a blissful state, happiness itself is a decidedly fragile state. The song’s final question is also ominous. Dylan appears to be suggesting that unless we ‘wake up’ and listen to the ‘divine music’ of the angels – which represents the possibility of human beings rising to a higher state of consciousness – then we as a race may be doomed.

After this, there is, it seems, nothing left to do but pray. The final track, Father of Night is based on the Jewish prayer Amidhah, which is always recited in a standing position. The supplicants are expected to praise God, ask Him for help and give thanks. One English translation runs:

…Bless us, our Father, one and all, with the light of Your face. For by the light of Your face you have given us, Lord our God, a Torah of life and love of kindness, charity, blessing, mercy, life and peace. May it please You to bless Your people Israel at all times and in every hour with Your peace…

Dylan’s song is a haunting little three verse piece, lasting only a minute and a half. He plays a repeated rhythmic line on the piano and is accompanied by the female vocalists providing atmospheric …ooohs… in between the verses. As on John Wesley Harding he uses deliberately archaic terms such as ‘taketh’, ‘teacheth’ and ‘shaketh’. The word ‘father’ appears at the beginning of each line except the fourth line of each verse. The song certainly praises God and gives thanks, although the narrator does not specifically ask for help. The ‘father’ portrayed here is not only identified as a beneficent force. He is said to take …the darkness away… to teach birds to fly, to be a …builder of rainbows up in the sky… to build mountains and shape clouds. He is not only a …Father of time, father of dreams, Father who turneth the rivers and streams…. and the father of grain, wheat, cold, heat, air and trees but also the …father of loneliness and pain… Although the song ends by dutifully stating that He is the …Father of whom we most solemnly praise… the narrator makes no demands on the deity. The song is a simple statement of belief in a patriarchal but non denominational God who controls all aspects of life and the universe. This God may …dwell in our hearts and our memories… but He is depicted as non judgemental and mainly benevolent.

Father of Night may be Dylan’s first avowedly ‘religious’ song but the God he praises seems to be closer to the ‘Great Spirit’ of Native American belief than a vengeful and cruel Jehovah figure. He is the God, perhaps, who watches over the sojourn in Paradise which is depicted in New Morning – a reassuring but ultimately distant figure. But what is most striking about this final coda to the album is its essential humility. Here is Dylan, the creator of so many linguistic ‘mountains and clouds’ and fantastical scenarios, apparently ‘bowing down’ and finally admitting that he feels he is subject to a higher power. Thus his pastoral dream world could at any time be swept away, leaving him to confront far more complex existential questions than he does in the songs of this period. The world of New Morning is thus a very fragile one and one which Dylan finally has to admit that he has little control over.

Links…

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

THE CAMBRIDGE BOB DYLAN SOCIETY

Leave a Reply