Several very distinctive love songs that Dylan composed around this time never made it onto his official albums, although these songs did tend to get ‘snapped up’ by other musicians. If You Gotta Go, Go Now is a light hearted romp which, like I Don’t Believe You, is based around a sexual encounter. As such it received several airplay bans. The song was a regular feature of Dylan’s final acoustic tours. It features on Live 64, The Bootleg Series recording of the 1964 Philadelphia Halloween show. Many of these early performances were accompanied by audience laughter. The song was rehearsed in acoustic form for the Bringing It All Back Home sessions but it soon became clear that it worked better as rock and roll. Various takes of the ‘electric’ version appear on The Cutting Edge. However, the song was omitted from the album and only released as a standalone single in The Netherlands, where it failed to make any impact. The British group Manfred Mann’s cover, which followed a similar template to Dylan’s later recordings, was a big hit for the band in the UK in 1965. In 1969 a bizarre and very jokey version with French lyrics became the only hit single for Fairport Convention.

The suggestiveness of If You Gotta Go is reminiscent of many blues numbers. With its many witty lines it also recalls the quick-fire lyricism of Chuck Berry. Its quick pace, driving beat, droll lyrics and offhand delivery also identify it clearly as being influenced by The Beatles, who were as celebrated as much for their naturally witty personalities as their music. The song consists of pleas by a horny young man for a girl to spend the night with him. In order to persuade her he employs a number of tricks. Firstly he begins with the obvious: …Listen to me baby, there’s something you must see/ I want to be with you girl/ If you want to be with me…. In the chorus, he makes sure that consent is achieved but cheekily tries to imposed his own ‘conditions’: …If you gotta go, it’s all right/ But if you gotta go, go now/ Or else you gotta stay all night… He is being forceful, of course, but in a charmingly funny rather than an aggressive way. The song has three other verses in which the attempts at seduction continue. Perhaps the funniest is the second, which runs …It ain’t that I’m questioning you/ To take part in any kinda quiz/ It’s just that I haven’t got no watch/ An’ you keep asking me what time it is…. Later he declares, perhaps ironically that …I certainly wouldn’t want you thinking/ That I don’t have any respect… Finally he declares that she must stay because …I’ll be sleeping soon/ And it’ll be too dark for you to find the door…

I’ll Keep It With Mine was first recorded in the final Witmark Demos session in June 1964. A more committed version (released in 1985 on the Biograph compilation) was recorded at the first Bringing It all Back Home session. Both featured Dylan on solo piano. Later, several attempts were tried out for Blonde on Blonde. But the song did not appear on any of his studio albums in the mid-60s or in his live sets. This is surprising, as it is a highly effective and tightly constructed ballad in which, still experimenting with the form of the love song, Dylan examines the vagaries of love from an unusual angle. The song concerns a couple who, for whatever reason, do not really ‘fit’ together. This was the kind of subject matter that was still unusual in mainstream pop music, although such subjects were meat and drink to country songwriters who specialised in the vagaries of domesticity. Kitty Wells 1952 hit It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels deals with marital infidelity without pulling any punches. In confessional songs like Crazy Heart and You Win Again Hank Williams examines love with the kind of fatalism that hangs over I’ll Keep It With Mine.

The song has only three verses but manages to convey a powerful sense of how some people are just not suited to be in a relationship with each other. The language is again straightforward but with many clever twists. The lyrics appear to be merely sketching out the parameters of this relationship, leaving us to fill in most of the details. The chorus: …If I can save you any time/ Come on, give it to me/ I’ll keep it with mine… is mysterious. The narrator seems to be asking the girl to donate some time (or perhaps memories) to him. The title phrase seems to suggest some dark inner feelings or secrets that the narrator feels he must keep to himself.

Dylan begins with rather tongue twisting and somewhat tragic lines: …You will search babe, at any cost/ But how long, babe, can you search for what is not lost?… Just like the mismatched couple in the song, we will never find out ‘what was not lost’ but the suggestion seems to be that this missing element was never present in the first place – i.e., the couple did not really love each other in a meaningful way. Although we hear that …Everybody will help you / Some people are very kind…. this tells us very little except that the object of the song – and presumably the narrator as well – is in considerable distress. The second verse begins with more convoluted lines: … I can’t help it if you might think I am odd/ If I say I’m not loving you not for what you are/ But for what you’re not… This is certainly ‘odd’. The confession of love here is hardly romantic and possibly somewhat demeaning. Although the next lines repeat the earlier sentiments: …Everybody will help you discover what you set out to find… we are never told what she is searching for.

The final verse has some similarities to Robert Johnson’s classic fatalistic blues Love in Vain (later recorded by The Rolling Stones) which also refers to a train leaving, on which the singer’s lover will depart. But this does not resolve the situation. We are told that …The train leaves at half past ten/ But it will back in the same old spot again… and that …the conductor, he’s weary/ He’s still stuck on the line… In blues songs, trains generally leave towards some particular destination. But here the train is stuck in some kind of loop. The figure of the weary conductor seems to have merged with the narrator, who is ‘still stuck on the line’. The song thus creates a vivid picture of two people who are trapped in a relationship which they need to end but cannot find the means to do so.

Marianne Faithfull’s take on the song is suitably strung out and anguished. Nico, who Dylan supposedly wrote the song after their brief affair in 1964, recorded the song in 1967 in a highly individualistic version with her trademark stern vocal style. The definitive version, however, is surely that of Fairport Convention (from their album What We Did on Our Holidays, 1969) who build the song up from Richard Thompson’s simple strummed guitar lick into a magnificent full band performance, gradually introducing more and more instruments as the song comes to a climax. Sandy Denny gives one of her greatest ever performances, modulating her voice between the quiet, almost whispered, tones on the verses and the full throated expression of the choruses. These changes of pace fit the ambiguous nature of the song perfectly. Richard and Linda Thompson performed the song in concert several times with a similar arrangement.

FAIRPORT CONVENTION (1969)

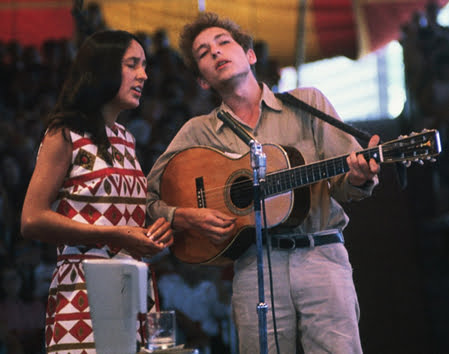

Love Is Just a Four Letter Word, also written around this time period, is one of Dylan’s least known songs, mainly because there is no record of him recording it, even on bootlegs. It is most associated with Joan Baez, who has claimed in a number of interviews that she rescued it ‘from the back of a piano’ when Dylan had forgotten it. This is a little hard to believe, as it is one of Dylan’s must subtle and unusual pieces. It is also quite possible that when he wrote the song he was caught in (at least one) ‘love triangle’ involving Baez herself. Perhaps he actually intended to give the song, which seems far too carefully constructed to be a ‘throwaway’, to her. Her extraordinarily pure cut glass vocal style certainly suits its detached and wistful tone. But the song is not in any way ‘about’ her relationship with Dylan.

The title phrase is a common aphorism which has been around since the 1920s, generally depicting a cynical view of love. However, the term ‘four letter word’, which is generally associated with swear words, can also be a simple description without such connotations. Dylan plays on this ambiguity in a song in which he addresses the nature of love itself, despite the fact that that none of the characters actually appears to be in love. But the narrator’s observation of a broken love affair leads him to come to certain philosophical conclusions regarding the true nature of love itself.

The song begins with the narrator looking back at a meeting with a woman in a café. The first lines draw us into the story with the mysterious statement …Seems like only yesterday I left my mind behind… which already seems to indicate that this will be a ruminative piece. The meeting takes place …down in the Gypsy Café with a friend of a friend of mine… This ‘friend of a friend’ has a new born baby which …sits heavy on her knee…indicating that she is a single parent. We might now expect the woman to relate a tale of woe but instead she declares the she is happy to be free from what she describes as ‘slavery’ (presumably the relationship or marriage to the narrator’s friend). We are told that her eyes …showed no trace of misery… Despite this, first use of the title phrase as a refrain seems to indicate the narrator’s view that she has been abandoned and that, in her case, love is indeed a ‘dirty word’.

We are then presented with a highly atmospheric description of the scene outside the café: …Outside a rambling store front window, cats meowed ‘to the break of day… It appears that the narrator and the woman have been engaged in an intense all night conversation. Perhaps the narrator has been making an appeal to her on behalf of his friend. But, like those wailing cats, whatever he has said has been just so much noise. He confesses that he is out of his depth in this situation: …Me, I kept my mouth shut, I had no words to say…. and admits that …my experience was limited and underfed… He then listens in as she talks to the father of the baby, who has presumably just arrived. We may presume that he wants to be reunited with her, or is offering to take some responsibility for the child. The details of the conversation are not revealed. The narrator, who has hidden away but is secretly listening in, hears her repeat the title phrase, which clearly indicates that she is not in love with the father.

After this spot of eavesdropping the narrator leaves the scene quietly to return to his own chaotic love life, which he describes as …drifting in and out of life times unmentionable by name… He also says he has been …searching for my double… Dylan is famously a Gemini. The narrator here seems to suggest that his search for love is an impossible quest as really he is just looking for a mirror image of himself. He tells us that he has been …looking for/ Complete evaporation to the core…. as if he expects that when he finds love, his creative spirit will be drained. In any case, the search for his soul mate has been unsuccessful. He tells us that: … I tried and failed at finding any door… Given that this search for love has dominated his life, he now finds the notion that ‘love is just a four letter word’ absurd. Of course, he reasons, love is much more than that…

In what was probably intended to be the final verse, the narrator now speaks from the present day. He reflects back on the woman’s conversation with her ex-partner, saying that he never quite understood her point of view when she used that ambiguous phrase. But now, having experienced multiple attempts to find love, he realises that she was right. The next few lines are among the most anguished and heartfelt in Dylan’s entire oeuvre: … After waking enough times to think I see/ The holy kiss that’s supposed to last eternity/ Blow up in smoke, it’s destiny/ Falls on strangers, travels free… He defines the kind of idealised love he has been searching for in religious terms. A ‘holy kiss’ (otherwise known as a ‘kiss of peace’) is a traditional ritualised Christian greeting. In St. Paul’s Epistle to the Corinthians 16:20 followers are instructed to …Greet one another with a holy kiss… Here Dylan transforms this into a description of how love is described in all those sentimental songs. But now he depicts it as exploding, and spreading its constituent parts quite randomly. Thus, finding love is not impossible but is largely a matter of luck. If a piece of the shattered ‘holy kiss’ reaches you, you may be blessed to achieve this ‘spiritual’ union with a partner.

This revelation leads the narrator to conclude that …I know now that traps are only set by me… He realises that he has been making it impossible for him to find this ‘holy love’ by setting artificial parameters. He now tells us that he does …not really need to be assured/ That love is just a four letter word… But now the meaning of the phrase has changed. ‘Love’ itself is not ‘a dirty word’ or a curse that creates torturous pain. It is, after all, just a word. And words, as this and so many other Dylan songs demonstrate, can be interpreted in many different ways. When placed in different contexts (or when sung differently) they may change their meanings. Thus the narrator realises that love can take many forms. Even if one finds a supposedly perfect partner, the relationship may not last ‘for eternity’. Love itself will change as years go by and may morph into many different shapes. The realisation that ‘love’ is merely an ambiguous concept, rather than a definite description of a goal one must reach, helps him recognise that this single word is inadequate to describe the range of feelings and behaviours it is usually taken to signify. The narrator has only discovered this revelatory truth by observing love – or the lack of it – in others.

The final verse that Baez sings is rather controversial. In the official lyrics the ‘holy kiss’ verse concludes the song. This seems entirely logical given its revelatory nature. But Baez, in her recorded version, adds an extra verse. Some commentators have theorised that Baez actually wrote this verse as it appears to be directed from her to Dylan. Certainly the poetic diction is less assured than in the rest of the song. The opening: …Strange it is to be beside you/ Many years the tables turned… is awkwardly ungrammatical, as are the following lines: And it is very, very weird indeed/ To hear words like forever, fleets/ Of ships run through my mind, I cannot cheat/ It’s like looking in a teacher’s face complete…. The ‘fleets of ships’ metaphor sits rather awkwardly with the rest of the song. Perhaps the most effective lines are those in the simple conclusion: …I can say nothing to you but repeat/ That love is just a four letter word… Baez seems to be acknowledging that Dylan has been her ‘teacher’ – not just about music, perhaps, but about love. She has performed the song on many occasions. In live shows, however, she has almost always omitted Dylan’s final verse and substituted it with her own, which – despite it lacking the poetic grace of Dylan’s words – may have been much truer to her own feelings.

Bringing it All Back Home features two quite beautiful love songs which appear to provide some resolution to Dylan’s journey through the vicissitudes of love. His songs now take on multiple layers of ambiguity. She Belongs to Me is here a slow, gentle blues; although in its multiple iterations throughout Dylan’s career it has taken many forms. The version which appears on Self Portrait, recorded at the Isle of Wight in 1969, presents it almost as a mock show tune. There are many covers, including a meditative performance from Jerry Garcia and Dave Grisman (1992), a raw vocal version by Leon Russell and an extended prog-rock extravaganza by The Nice (1969). The song is fairly minimal, consisting of just four short verses. In traditional blues manner, the first two lines of each verse are repeated. This has the effect of underlining the narrator’s devotion to his subject, who he seems almost to worship. Certainly he seems quite prepared to sublimate himself to her wishes.

The woman (who certainly cannot be called a ‘girl’) seems to be emotionally mature, immensely self assured and self confident. She has her own independent artistic life, which Dylan celebrates: …She’s got everything she needs/ She’s an artist, she don’t look back… In his eyes she has magical gifts which have turned his view of the world upside down: …She can take the dark out of the night time and paint the daytime black… In the second and fourth verses he switches the mode of address to ‘you’, so broadening the scope of the song. He continues: …You will start out standing/ Proud to steal her anything she sees/ But you’ll wind up peeking through her keyhole down upon your knees… intimating that his love for this powerful woman will be so intense that he will even break the law to please her. The last line has definite sexual connotations, with the suggestion that the woman will dominate him sexually. He devotes himself to her pleasure while on his knees by giving his attention to her ‘keyhole’. Clearly this is the same orifice as in Virginia Liston’s 1924 blues You Got the Right Key but the Wrong Keyhole.

The second half of the song again begins with a description of the woman’s qualities. We hear more testimonies to her strength of character; … She never stumbles, she got no place to fall … and that …She’s nobody’s child, the law can’t touch her at all… There is a slight nod to the famous tearjerker Nobody’s Child, first recorded by Hank Snow in 1949. But here the phrase, originally describing a pitiable figure, becomes another mark of the woman’s independence and power. In one of the song’s most striking images, we hear that …She wears an Egyptian ring that sparkles before she speaks…. This suggests that she has magical or entrancing qualities …She’s a hypnotist collector, you are a walking antique… reverses the conceit of the title phrase, which is now revealed as being ironic. In fact the singer ‘has become part of her ‘collection’. The song ends in typically low key blues style. The instruction is given to …Bow down to her on Sunday, salute her when her birthday comes/ For Halloween buy her a trumpet, for Christmas give her a drum… It seems that, in the singer’s mind, this ethereal creature requires such ritualised tributes.

Love Minus Zero/No Limit can be seen as the culmination of this series of songs. Here Dylan’s poetic powers are fully invoked, so that even its simplest lines can set off multiple interpretations. As with She Belongs to Me, the female subject is idealised and given ‘special powers’. But Love Minus Zero is more consciously poetic, employing a number of literary allusions with much shifting and surreal imagery. In many ways this lyrical complexity foreshadows Dylan’s work in his densely ambiguous songs of the late 1990s and 2000s. The way the title, which does not appear in the song, is presented is very unusual, with a forward slash between its two parts. At the time Dylan insisted that this was a mathematical formula. ‘Love divided by nothing’ can, of course, only result in ‘infinity’. The song is indeed an awesome celebration of a love which is simultaneously limitless and grounded in reality.

The song’s unusual variation of rhyme, pararhyme and no rhyme is used for considerable effect. Each four line verse begins with a rhyming couplet, followed by a non-rhyming line.. The final line of each set of two verses rhymes with that of the next verse. This structure creates a sense of anticipation, as we wait patiently for the rhymes to arrive. The lyrics have a certain contradictory logic which seems to indicate the influence of Zen Buddhism, or at least the ‘intellectual’ version of Zen that had so influenced the Beat poets as well as Dylan’s soon-to-be wife Sara. The woman is not, as in She Belongs to Me, some kind of ‘goddess’ to be worshipped. In many ways she appears to be quite down to earth. She certainly exudes a philosophical calm which the narrator appears to be highly impressed by.

The first verse begins with an immediate logical paradox. We are told that …My love, she speaks like silence… The sense of apparent contradiction recalls the first line of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 130: …My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun… The narrator seems to be asserting that his lover is an extremely wise woman who can sum up any situation in a few quiet words. We learn that she has …no ideals or violence…. He seems to have absolute trust in her. This is summed up in the next, brilliantly compressed but extremely evocative lines: …She doesn’t have to say she’s faithful/ But she’s true like ice, like fire… The juxtaposition of ice and fire not only suggests that she will never betray him but also gives a sense of cosmic balance, of yin and yang in perfect harmony.

In the next verse, we learn that the narrator’s lover cannot be ‘bought off’ by sentimental gifts: …People carry roses, and make promises by the hours/ My love she laughs like the flowers/ Valentines can’t buy her… She remains incorruptible. There are echoes here of the seventeenth century poet Robert Henrick’s To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time, which begins: …Gather ye rose-buds while ye may/ Old time is still a-flying/ And this same flower that smiles today/ Tomorrow will be dying… as well as more lines from Sonnet 130: …I have seen roses damasked, red and white/ But no such roses see I in her cheeks… There are also hints of Blake’s Sick Rose, Wordsworth’s Daffodils and the famous anti-war folk ballad Where Have All the Flowers Gone? In all of these works, flowers are animated symbols of pure love and beauty, even if they have been corrupted. Yet the mention of ‘Valentines’ (greeting cards which are often accompanied by flowers, especially roses) indicates that her affection cannot be bought.

Having established his lover as a kind of pure, ethereal spirit, Dylan then examines various aspects of the ways in which many people spend their lives attempting to find truth, happiness and fulfilment, with the wonderfully succinct …In the dime stores and bus stations/ People talk of situations/ Read books, repeat quotations/ Draw conclusions on the wall… He appears to be suggesting that much of this philosophising is rather futile. His lover …knows there’s no success like failure, but failure’s no success at all… another apparently contradictory ‘Zen koan’ which may be a way of expressing the fact that fame and success do not necessarily bring understanding of other people.

The imagery in the following verses becomes increasingly surreal, leading the listener off in a number of different directions. We hear that …The cloak and dagger dangles/ Madams light the candles/ In ceremonies of the horseman/ Even the pawn must hold a grudge… The chess-related metaphor, with the unforgettable phrase ‘ceremonies of the horsemen’ suggests a kind of ritualised warfare, which the ‘pawns’ in ‘their game’ naturally object to ‘Cloak and dagger’ is a slightly comical description of shady dealings which here appear to hang, presumably like the Sword of Damocles, over people’s heads. In a reversal of traditional morality, the ‘madams’ – who may be brothel keepers – are apparently showing their religious devotion by lighting candles.…Statues made of matchsticks crumble into one another… is a beautifully expressed summary of the futility of human aspiration. But the narrator’s lover is apparently not affected by this as …She knows too much to argue or to judge… Again, her non-judgemental qualities are held in high esteem.

We are then presented with a series of fleeting images, many of which seem to be related to literary texts. The surreal phrase …The bridge at midnight trembles… seems to be related to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem The Bridge, whose protagonist stands …on the bridge at midnight… contemplating a lost love, who has presumably died …The country doctor rambles… may refer to Franz Kafka’s short story A Country Doctor, a bizarre tale of medical failure with an extremely unreliable narrator …Banker’s nieces seek perfection… appears to refer to Henry James’ The Portrait of A Lady, whose heroine Isabel Archer is a banker’s niece who attempts with limited success to negotiate the pitfalls of marriage in a misogynistic society. She certain does not find ‘perfection’. We are told that these characters are …expecting all the gifts that wise men bring… which will presumably not appear. These are people who are left to contemplate their own failure to achieve what they had set out to do in life. As such they are the opposite of the narrator’s lover, who realises that such striving to reach impossible goals is futile.

In the final verse the surreal image …The wind howls like a hammer… suggests the presence of a mighty storm. This is confirmed by …the night blows cold and rainy… Finally we are left with the haunting …My love, she’s like some raven/ At my window with a broken wing… suggesting that, although the lover may be a wise philosopher, she still needs the narrator’s protection. In the Icelandic sagas the raven represents wisdom, while in Native American mythology it is a symbol of change and transformation. Some commentators have compared this raven to the subject of Edgar Allan Poe’s celebrated poem. But that raven is a harbinger of death and depression whereas this raven is a beautiful but damaged creature. Dylan’s raven is closer to the much more sympathetic bird in Blake’s The Human Abstract, which makes its nest in a hidden tree which …The Gods of the earth and sea/ Sought thro’ Nature to find… In this remarkable final image it is suggested that, despite the subject of the song being so self-possessed, life has been rather cruel to her. The narrator sincerely intends to protect and heal her. This seems to indicate that she needs him as much as he needs her. Thus she is not, like the woman in She Belongs to Me, a dazzling figure to ‘bow down to’.

Love Minus Zero is a remarkable fusion of the poetic techniques which Dylan had picked up from his extensive reading and the traditions of the blues and country music which form the bedrock of his art. Despite its use of dreamlike imagery and logic it is a very real and extremely moving evocation of love which, after the heartbreak of songs like Ballad in Plain D, I’ll Keep It With Mine and One Too Many Mornings and the uncertainty of Love is Just a Four Letter Word, seems to represent a considerable breakthrough. Dylan now seems unburdened by the pain of love he has experienced in the past. Soon, on Blonde on Blonde, which is largely an album of love songs, he will extend the possibilities of the genre even further to create the massive poetic tapestries of Visions of Johanna and Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands. The lovers in these highly ambiguous works are multidimensional creatures while the songs themselves tilt at universal truths. The characters in these songs, like the lover in Love Minus Zero, will become transformed – like the mythical figures in Ovid’s Metamorphosis – into representations of love itself, with all its attendant confusions and contradictions but also with its moments of ecstatic realisation and poetic transcendence.

Leave a Reply