“Who cares for you? You’re nothing but a pack of cards!”

― Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking-Glass

Intro: Lily, Rosemary….

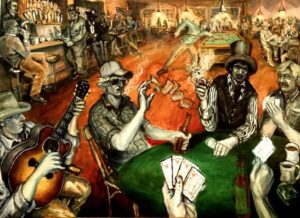

A cheerful, bouncy rhythm and a tongue in cheek presentation of its vivid scenario makes Bob Dylan’s epic ‘cowboy ballad’ Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts stand out from the darker songs on Blood on the Tracks. The song relates an ambiguous, ‘shape shifting’ story about how appearances can be deceptive, and as such is centred on a nameless, ephemeral character who may or may not be ‘real’. It provides an alternate take on the album’s overriding theme of doomed relationships. Its collection of characters – gamblers, showgirls, bank robbers and a drunken judge – come straight out of cheap vintage comics or old fashioned Western movies. They could be said to be quite deliberately ‘one dimensional’.

This is one of Dylan’s most appealing and enigmatic songs, full of witty rhyming, various poetic devices and characteristically colloquial turns of phrase. Like The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest (its most obvious antecedent) it is a comic narrative which can be interpreted in many different ways. As with other songs on Blood on the Tracks, we are not certain whether the story in the song is told chronologically. Only certain selected details are presented, as if we are watching a movie shot in the style of early 60s French New Wave directors such as Francois Truffaut and Jean Luc Godard, which has been quite heavily edited using ‘jump cuts’. The song also anticipates the deliberately cinematic writing on Desire.

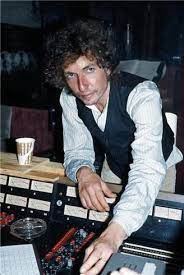

Lily… Recordings

Lily has a rigid lyrical format and a repetitive musical structure, with no choruses but with every verse ending in the title phrase. It has fifteen verses (sixteen in the original version) all of which consist of two rhyming couplets, followed by a non-rhyming line ending in the title phrase. Dylan’s original acoustic recording from the ‘New York Sessions’ for Blood on the Tracks (which appears on the Bootleg Series release More Blood, More Tracks) drags a little because of a lack of musical texture. But the addition of bass and drums on the final version creates a swinging mood which is very much in tune with the song’s playful nature. Surprisingly, though, Dylan has only ever played the song live once, at Salt Lake City on 25th May 1976. Sadly there is no known recording of this show.

Roving Gamblers

Lily is a bizarre and sometimes surreal addition to the long established tradition in American popular song forms which uses cards or gambling as a metaphor for the vicissitudes of life. The gambler is a stock figure in the mythology of Americana, personified in numerous Hollywood films (such as Gunfight at the OK Corral, 1957) by the legendary figure of Doc Holliday, a sharp talking, whiskey-swilling gunfighter. Numerous folk, country and blues songs are concerned with gambling. Many of these – such as Railroading and Gambling (Uncle Dave Macon, 1924), Jimmie Rogers’ Gambling Bar Room Blues (1932) and Gambling Women Blues (Memphis Minnie 1935) – deal with the destructive consequences of the practice, especially when it is accompanied by excessive drinking. Other songs seem to portray gambling almost as a sacrament. Blind Willie McTell’s slyly satirical Dying Crapshooter’s Blues (1949) describes the gambler laying out plans for his own ornate funeral. Tex Ritter’s ultra-religious spoken word monologue Deck of Cards (1948) treats the cards as nothing less than holy objects. The protagonists of many of these songs are emblematic of the quintessentially American figure of the gambler as a ‘freedom loving’ outsider from the daily grind of ordinary life.

TEX RITTER

Dylan has performed the traditional song The Roving Gambler, which epitomises this notion, in concert over 50 times. His 1963 song Rambling, Gambling Willie (which appears on The Bootleg Series Vols. 1-3) recounts the life of Willie O’Conley, a highly idealised fictional gambler who …had twenty seven children but he never had a wife…. before he is gunned down in a saloon. The song makes it clear that, despite his wild ways, Willie is an old fashioned hero to be celebrated. But the Jack of Hearts is a very different kind of character. He is smooth, calculating…. an expert, perhaps, at melting into a crowd.

He is, as they say, ‘a card’.

Nothing But a Pack of Cards

There is a tradition in both song and literature in which specific playing cards represent or even turn into particular individuals, most famously in Lewis Carroll’s Alice Through the Looking Glass. In Sippie Wallace’s Jack O’ Diamonds Blues (1926) the ‘Jack’ is clearly a male lover. There are echoes of such songs in the Rolling Stones’ classic Jumpin’ Jack Flash (1969). Some Other Kinds of Poems, Dylan’s sleeve notes for the Another Side album (1964), includes one poem which riffs around the traditional song Jack O’Diamonds. A 1964 song of the same title by Ben Carruthers and The Deep (later covered by Fairport Convention) sets this to music and is credited to Dylan/Carruthers. In fact this version uses little of Dylan’s poem and is closer to the traditional song (which had been recorded by Blind Lemon Jefferson, Mance Lipscomb, Leadbelly, Lonnie Donegan and many others) with its refrain of …Jack O’Diamonds is a hard card to play…

BOB DYLAN IN 1975

In the traditional playing card pack, the jacks of hearts and spades are known as ‘one-eyed jacks’ because they are pictured facing sideways, whereas the jacks of clubs and diamonds show the whole face of the figures. In the game of five card stud, the one-eyed jacks are ‘wild’ cards which can take the place of any other cards – thus representing enigmatic, unpredictable and mysterious characters. One-Eyed Jacks is also the name of a visually dazzling 1961 ‘revisionist western’ (a development of the genre which questions the usual Western stereotypes) starring Marlon Brando, in his only directorial effort. Ballad of the One Eyed Jacks (1961), a song by Johnny Burnette, which was released to tie in with the movie, personifies the characters as ‘playing cards, and includes the lines: …Never trust a one-eyed Jack with his cold, cold heart of stone/ He will only show one side to you, for his soul is the devil’s own… One of Dylan’s earliest songs, the unfinished One Eyed Jacks (circa 1961), of which an almost inaudible recording exists, includes the lyrics: …The queen of his diamonds/ And the jack his knave/ Won’t you dig my grave/ With a silver spade …..

MARLON BRANDO in ‘ONE EYED JACKS’

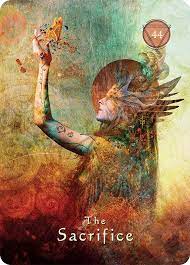

The playing card deck has links to the Tarot, from which it originally evolved. Tarot related imagery appears in several songs from Dylan’s mid 70s albums such as Isis and Changing of the Guards. According to the website https://cardarium.com the Jack of Hearts is a birth card for anyone born between the 24th and the 30th May. In this system, the Jack of Hearts is known as the ‘Sacrifice Card’ and represents a selfless and generous person who has a thirst for knowledge and a great desire to spread this to as many people as possible, yet have not necessarily had a full formal education. Such individuals, like Dylan, have largely educated themselves.

Incidentally, the 24th May is Bob Dylan’s birthday.

Opening Shots

Action! The first two lines set up the scene with some ominous pronouncements. It is as if we are following a camera in a sweeping panning shot across a typical small town Western scene, which then zooms in- Hitchcock style – on the main protagonist. We hear that …The festival was over, the boys were all plannin’ for a fall/ The cabaret was quiet, except for the drillin’ in the wall /The curfew had been lifted and the gamblin’ wheel shut down… The phrase ‘planning for a fall’ appears to be a variation of ‘heading for a fall’, except for the fact that ‘the boys’ are destined to succeed in their efforts. But we will learn nothing about the nature of the ‘festival’ that has just ended, why there was a curfew or why what is presumably a roulette wheel had been closed down.

The sound of ‘drilling’, which goes on in the background of the song – yet is apparently not heard by the characters – will later be revealed to be created by ‘the boys’ in their attempt to rob the bank next door. This is a decidedly revisionist Western, as if Fellini or Bunuel had been let loose on some disused Hollywood set. Given that the rest of the song seems to build up to some kind of onstage performance, it may be that this verse actually describes the end of the action, not the beginning; much in the manner of a film such as Citizen Kane, which constructs its entire story through non-chronological flashbacks.

In an aside that might have come from a worried citizen in a typical Western, Dylan sings …Anyone with any sense had already left town… We can certainly assume that there trouble is brewing in this ‘one horse town’. We cut to a ‘close up’ of our main protagonist, who is. … standin’ in the doorway, looking like the Jack of Hearts… Presumably he is facing side on, as he is a ‘one eyed Jack’. We are not told that he is the Jack; merely that he looks like him. This establishes the theme of ambiguous identity that will be prominent in the song. The Jack is a ‘wild card’.

Dylan moves the narrative forward with great poetic skill, using five internal rhymes: …plannin’, drillin’, gamblin’, standin’ … and …lookin’… His tongue then glides over some muted alliteration: …He moved across the mirrored room… This sets up another cinematic device, allowing both the listeners and the other characters to view the Jack from a variety of different angles. He issues the order …”Set it up for everyone”… It is unclear what he is referring to here – perhaps the gambling wheel, although there are no more references to this in the rest of the song.

The next line is another cinematic tour de force and a great example of Dylan’s lyrical dexterity. We hear that …Then everyone commenced to do what they were doing before they turned their heads… as if we had suddenly witnessed a freeze frame; a technique used prominently in the famous final shot in one of Dylan’s favourite movies, Truffaut’s The 400 Blows. The Jack swaggers around the saloon, grinning as he enquires when ‘the show’ will begin. However, no such show will actually be described in the song. Perhaps it is actually here, rather than the first verse, that the real action begins. The second verse ends with a brilliantly compressed expression of the notion that the protagonist is both a person and a playing card: …Then he moved into the corner, face down like the Jack of Hearts… The use of the term ‘face down’ – a term for a potentially winning card which the player has not yet revealed – suggests that the Jack is hiding away in the shadows, biding his time.

FINAL SHOT OF THE 400 BLOWS

A Queen Without a Crown

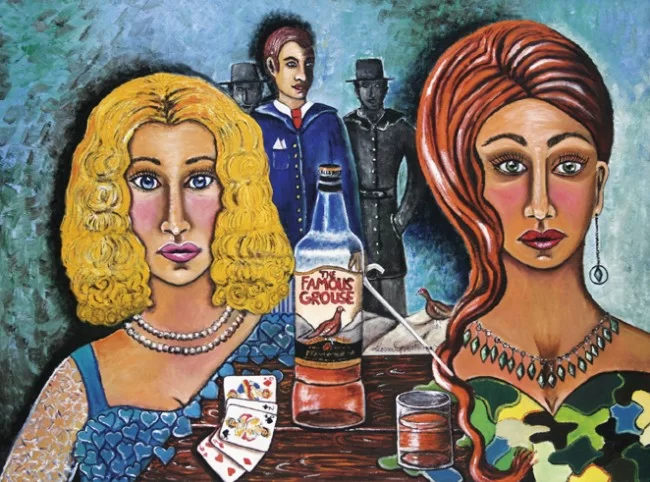

The notion that the action in the story is occurring simultaneously in real life and a card game is made even more explicit in the next verse, where we hear that ‘the girls’ (presumably Lily and Rosemary) are engaged in a round of five card stud, a very popular version of poker in late nineteenth century America. It is also the title of Henry Hathaway’s 1968 movie, starring Dean Martin and Robert Mitchum, about murders that follow accusations of cheating in a card game. It seems that Lily is on the point of winning the game, as she has two Queens and is hoping to gain a third to complete her hand. But she fails to obtain this card and (naturally) draws the Jack of Hearts. It is, yet again, even possible that here is where the real action of the song begins.

For the rest of the song, the Jack mainly stays in the shadows. Dylan concentrates on the other characters. We are introduced to the ‘Big Jim’, the ‘baddie’ in the story, who we are told …owns the town’s only diamond mine… The name was used for the hero of a series of cowboy novels written by the highly prolific Western author Marshall Grover. Dylan’s description of Big Jim is one of the highlights of the song. We are told that he was …lookin’ so dandy and so fine… and that …With his bodyguards and silver cane and every hair in place/ He took whatever he wanted to and he laid it all to waste… This highly colourful, compressed and highly cinematic description of the character gives us an immediate impression that he is a formidable villain. But, in another aside, we are assured that he will not be able to triumph over our mysterious hero: …But his bodyguards and silver cane were no match for the Jack of Hearts…

We are now introduced to Rosemary, who arrives …lookin’ like a Queen without a crown… The description again suggests that she herself is one of the playing cards – perhaps the Queen of Hearts, the next card up from the Jack. Queen of Hearts is a traditional song which has been recorded by Martin Carthy and Joan Baez, in which the playing card comparison again looms strong. The Queen has an unfaithful lover who is described as the ‘Ace of Sorrow’.

Rosemary enters the room and whispers…Sorry darling that I’m late… in Big Jim’s ear, indicating to us that she is his lover. But he ignores her, having just noticed the Jack of Hearts. …I know I’ve seen that face somewhere… he is thinking. Perhaps, in the manner of many cowboy films, he has seen him ‘…down in Mexico or a picture upon somebody’s shelf… In a number of Westerns (notably Sam Peckinpah’s elegiac Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973), for which Dylan composed the soundtrack and appears as the character of ‘Alias’, outlaws being pursued by the law take refuge in Mexico. Perhaps this picture on the shelf is a ‘Wanted’ poster.

Suddenly the lighting in the scene changes, as the show is about to begin. The story takes a rather surreal turn, as the house lights go down and we hear that …in the darkness of the room there was only Jim and him/ Staring at the butterfly who just drew the Jack of Hearts… The crowd who had been stamping their feet in anticipation now seem to have mysteriously vanished. Both characters seem to be focused on ‘the butterfly’ Lily, who is memorably described as …a princess/ She was fair skinned and precious as a child… We learn that Lily has had a colourful life, having had …lots of strange affairs/ With men in every walk of life… We are also told that she …had Jim’s ring/ And nothing would ever come between Lily and the King… Presumably she is married or engaged to Big Jim, who now is possibly characterised as another playing card, the King. The only person who might spoil their relationship, it seems, is (of course) the Jack of Hearts. There is a strong suggestion that Lily and the Jack have had a previous relationship. This is a very common motif in Western movies, where the women are often seen as pining for their outlaw men who frequently have to ‘leave town in a hurry’.

DYLAN AS ‘ALIAS’

Gazin’ to the Future

Rosemary is clearly jealous of Lily and ‘the King’. Now she …started drinking hard and seeing her reflection in the knife… another dramatically cinematic touch, suggesting that she is having murderous thoughts. She is said to be …tired of playing the role of Big Jim’s wife… suggesting that Big Jim is ‘two timing’ her with Lily. Her own background is as troubled as Lily’s: …She had done a lot of bad things, even once tried suicide… In her drunken state, she is clearly contemplating murder. She …was looking to do just one good deed before she died… But in another one of the ‘pay off lines’ there is a suggestion that everything that has been described is really part of the card game that she and Lily are playing, we hear that …She was gazin’ to the future, riding on the Jack of Hearts… Like Lily, Rosemary seems to be desperately hoping to draw the Jack so she can win the game. There are strong sexual suggestions here. Perhaps this is a memory of her and the Jack having sex, with Rosemary ‘riding him’ in the ‘cowgirl position’.

It seems, however, that the Jack is also romantically involved with Lily, who in the next verse is seen removing her dress. Little detail is given but we may assume that the couple have retreated to a separate room in the building to consummate their relationship. She mocks him flirtatiously: …Has your luck run out… Well, I guess you must have known it would someday… She expresses that she is glad that he is still alive and tells him he is …looking like a saint… Meanwhile, the ‘backstage manager’, suspecting that some mayhem is about to occur, tries to find the ‘hanging judge’. But the judge, as judges often are in Westerns, is drunk.

All this builds up to the climactic action in verse thirteen. What actually happens is not initially made clear. We had previously heard that …Down the hallway footsteps were comin’ for the Jack of Hearts… The murder scene is presented as if being filmed in dark ‘film noir’ shadows, so we do not know at first who has killed who: …No one knew the circumstance but they say that it happened pretty quick/ The door to the dressing room burst open and a cold revolver clicked… Many listeners have heard this as ‘Colt revolver’. However, the fact that it is said to have ‘clicked’ clearly indicates that the gun was not actually loaded. It seems that Big Jim and Rosemary have arrived to catch the Jack and Lily in flagrante. But the scene does not pan out as expected. We are told that …Big Jim was standing there, you couldn’t say surprised/ Rosemary right beside him, steady in her eyes/ She was with Big Jim, but she was leaning to the Jack of Hearts… The suggestion of her betrayal is clearly set out here. It seems that Rosemary has done her ‘one good deed’ but we do not yet know what has actually happened. As in all good Westerns, the suspense continues until the closing scenes.

A Penknife in the Back

There will, however, be no big shoot out in the end. We now cut to the gang of robbers, who have finally …made it through the wall… that they were drilling through earlier. They empty the bank safe and are seen waiting …for one more member who had business Back in town/ But they couldn’t go no further without the Jack of Hearts… The Jack, it now appears, is the leader of this ‘Hole in the Wall Gang’. Perhaps he has masterminded the whole operation, distracting Big Jim and his ‘bodyguards’ while the heist is going on. The penultimate verse begins with the wonderfully ominous …The next day was hangin’ day, the sky was overcast and black… Then all is revealed: …Big Jim lay covered up, killed by a penknife in the back/ And Rosemary on the gallows, she didn’t even blink… So it is Big Jim, rather than the Jack, who has been murdered. Rosemary appears to have no regrets and clearly accepts her fate.

By now, though, the Jack has disappeared, presumably to join his gang and make off with the takings from the bank. As so often happens in Westerns, he has left the women behind to mourn his departure. The song closes with a ‘close up’ of Lily, who was …thinkin’ ‘ bout her father who she very rarely saw/ Thinkin’ ‘bout Rosemary, and thinkin’ about the law…. Dylan uses repetition to considerable effect in the final (and perhaps inevitable line) …But most of all, she was thinking ‘bout the Jack of Hearts… The Jack is her elusive lover, who she may have hoped would free her from the ‘bad guy’. But, as Western heroes generally do, her hero has abandoned her as he ‘rides off into the sunset’.

You Can Dance To It…

In Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts Dylan inverts the usual conventions of the Western, with the women being the most active (and violent) protagonists. In the Tarot the Jack of Hearts is a symbol of hope and good fortune, often associated with ‘matters of the heart’. But the Jack himself is an evasive, slippery character. We do not even really know what he looks like. A number of ‘plot holes’ are deliberately left unfilled, so listeners are forced to project their own interpretations onto the narrative. Like many of the other songs on Blood on the Tracks, the actual nature of the events and the order in which they happen is deliberately obfuscated. While in Tangled Up in Blue, the narrative is fractured in terms of time, here the story is presented from a number of different viewpoints. The Jack of Hearts is never presented as a fully rounded character. He is a figure onto whom the other characters project their thoughts, hopes and dreams – rather like Dylan himself, whose fans have often pictured as ‘looking like a saint’.

The song has been interpreted in many different ways. Given its location on an album full of songs about marital breakup, some have been tempted to treat it as an allegory of Dylan’s own life, with Lily and Rosemary representing his own real life lovers like Sara, Baez and Edie Sedgwick. But despite its violent resolution the song is not dark or tragic. It is an essentially comic piece, full of sharply knowing lines and tongue in cheek rhyming. In twisting well known generic conventions around, Dylan appears to be teasing his listeners throughout, perhaps inviting them to place their own interpretations on the events and characters but then continually shifting from scene to scene to make any definite interpretations untenable. In that sense it could even be said to be a song about Dylan’s own song writing process. Like many of his most original songs (such as Desolation Row, Visions of Johanna, Jokerman or All Along the Watchtower) it is an ‘open text’, with many suggested layers of ambiguity – a kind of jigsaw puzzle which cannot ultimately be solved because many of the pieces are missing (as in Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands, the protagonist of which has a ….deck of cards, missing the Jack and the Ace…).

With its winning rhythmic pulse and the continual referral back to its central enigmatic figure, the song can be seen as a joyous mockery of those who either over interpret Dylan’s work or who produce dubious statements regarding what his songs are ‘really about’. In Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts Dylan peeks out from behind his ‘birth card’ and delights in throwing out clues to his own creative process. In doing so presents us with a trickily self referential comic masterpiece. Whatever its darkly existential qualities, and despite the narrative riddles it presents us with, it is always light hearted and funny. You can even, as a DJ friend of mine recently proved to his great delight, get people to dance to it!

This is a song that is impossible to tie down. Dylan delights in presenting us with a cavalcade of scenes that present us with riddles that, by their very nature, can never be solved. So the song is endlessly attractive, always glorious fun and – despite the fact that, unusually for a Dylan song, there is only one definitive version – it still provides us with a different experience every time we pick up that needle and bang it down onto the groove.

|

|

DAILY DYLAN NEWS at the wonderful EXPECTING RAIN

THE BOB DYLAN PROJECT- COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

Leave a Reply