Farewell! thou art too dear for my possessing,

And like enough thou knowst thy estimate.

The Charter of thy worth gives thee releasing;

My bonds in thee are all determinate.

For how do I hold thee but by thy granting,

And for that riches where is my deserving?

The cause of this fair gift in me is wanting,

William Shakespeare Sonnet 87

Everything seen…

The vision gleams in every air.

Everything had…

The far sound of cities, in the evening,

In sunlight, and always.

Everything known…

O Tumult! O Visions! These are the stops of life.

Departure in affection, and shining sounds.

Arthur Rimbaud Departure

Baby Blue….

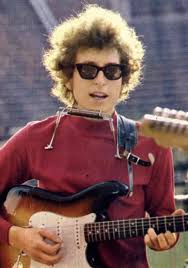

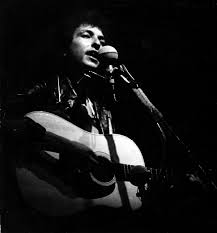

It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue is one of Bob Dylan’s most well known songs. It has a beautiful melody, a winning chorus and lyrics that can express many different moods. Dylan has performed it almost five hundred times and there are literally hundreds of cover versions. It presents us with a series of images which could be said to change meaning depending on whether the song is performed wistfully, angrily or with a sense of acceptance. In some ways it can thus be regarded as the quintessential Dylan song – one that means something different to every listener and whose meaning can be changed, varied or teased through the singer’s vocal inflections. Yet, despite performing the song in many different ways, Dylan has never felt the need to adapt or change any of the words.

One of the most remarkable things about the song is its adaptability to different musical genres, from Joan Baez’s folk purity to Hole’s grunge rock. Bryan Ferry treats it as a sprightly, up tempo sing-a-long. The Byrds’ version is slow and ruminative. Marianne Faithfull makes it anguished confessional. The Grateful Dead transform it into a reflective epic that goes through a number of different moods. Barb Jungr gives us a light, jazzy take. With some intense finger picking, Joni Mitchell makes it sound like one of her own songs. Perhaps the definitive cover is one of the earliest – the souped up rhythm and blues version by Them (1965), featuring an anguished and impassioned vocal by Van Morrison, on which many of the other covers are based.

Baby Blue….

Dylan’s use of language in the song is essentially playful. In choosing a title, Dylan claimed to have been inspired by Gene Vincent’s rock and roll classic Baby Blue, a powerful piece of teen pop. The term ‘baby’ (or ‘babe’) is ubiquitous in the blues, country and other American forms of music as an endearment between lovers – male or female. A great example is Elvis Presley’s seminal Sun sessions recording Baby Let’s Play House (1954), part of which consists of ‘The King’ mumbling and spluttering …baby, baby, baby… There is also a common expression ‘baby blue eyes’, which refers to the term ‘baby blue’, meaning a very light shade of the colour, but can also be used to describe a person who is particularly attractive. The use of the term ‘baby blue’ allows the singer to be sweet and sarcastic at the same time. There is also a strong contrast between the apparent childlike quality of the name and the finality of …It’s All Over Now... (itself the title of an early Rolling Stones hit). Dylan famously has ‘baby blue eyes’, which tends to suggest that the song may be – at least on one level – directed at himself.

ELVIS PRESLEY GENE VINCENT

The song follows a rigid pattern, although the order of the verses is potentially interchangeable. The verses have six lines, consisting of three rhyming couplets and each builds to a climax in the same way. The first couplet tends to use extended syllables, while the second is shorter and calmer. The first couplets consist of direct addresses to ‘baby blue’ while each of the second couplets refers to a particular individual. These couplets are distinguished by poetic devices that contain a kind of hallucinatory symbolism which bears the influence of French symbolist poets like Rimbaud and Verlaine. The first line of each of the final couplets consists of a direct warning or instruction before the repetition of the title itself in the last line.

The first couplet is a rather delicious tongue-twister: …You must leave now, take what you need, you think will last/ But whatever you wish to keep you better grab it fast… The identity of the narrator who is making this appeal is not revealed, although the slightly distant tone suggests that it is not the ex-lover who is mentioned later on in the third verse. The emphases on the words ‘need’ and ‘keep’ are crucial dramatic points on the portentous line, which suggests that some major destructive event is on the way.

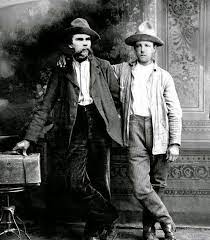

Baby Blue and Baudelaire

We then jump into one of the song’s most powerful images: …Yonder stands your orphan with his gun/ Crying like a fire in the sun… The use of the slightly archaic ‘yonder’ is particularly effective here, literally ‘distancing’ us from the image. The remarkable ‘crying like a fire in the sun’ can be read several ways. It may be sympathetic, suggesting that the ‘orphan’ is crying genuine tears, but his or her feelings are being overshadowed by bigger events. Alternately, this may suggest that the ‘crying’ is completely futile, as making a fire when the sun is shining is obviously not necessary. The imagery is reminiscent of the way symbolist poets use natural phenomena to reflect emotional realities and elements of poetic vision. Rimbaud’s poem Eternity describes that ineffable state as …the sea mingled with the sun… In Verlaine’s A La Promenade …The sifted golden sun comes to us blue/ And dying, like the sunshine of a dream…. Baudelaire’s The Sun refers to it as …our nourishing father, anaemia’s deadly foe/ Makes poems, as if poems were roses, bud and grow…

VERLAINE AND RIMBAUD BAUDELAIRE

The identity of the ‘orphan’ is one of the song’s mysteries. ‘Your orphan’ may or may not suggest that this is the child of ‘baby blue’. Perhaps the narrator is asking her to consider that when she leaves – as he is telling her she must – her child will be left alone and disconsolate, crying futile tears. Or perhaps her own child has shot her and the rest of the song is her life flashing before her eyes. The ‘orphan’ may be purely an aspect of herself stuck in a hopeless situation. As in symbolist poetry, the imagery is fleeting and invites multiple interpretations.

The penultimate line consists of a warning: …Look out, the saints are coming through!… This appears to be, by way of an inferred reference to the popular traditional gospel song When the Saints Go Marching In, an evocation of millennial or apocalyptic imagery. According to the Book of Revelation, on Judgement Day all the martyred saints will make a glorious return to Earth. In this case, the image of the ’saints coming through’ represents a revelation of the truth which Baby Blue is experiencing: that her life needs to undergo rapid change in order for her to survive. This message is expounded in the following verses in different ways.

THE DAY OF JUDGEMENT

The second verse begins with two of Dylan’s most quotable lines. Although they may be seen, on a more obvious level, as advice to the woman as to how to survive her situation, their resonance goes much further …The highway is for gamblers, better use your sense… Dylan sings …Take what you have gathered from co-incidence… The fusion of blues imagery and Taoist philosophy being expressed here is at the absolute core of Dylan’s poetic method. In the blues the highway is a metaphor for the routes life may take. Gamblers in the blues are wild cards, chancers… The statement ‘the highway is for gamblers’ implies that life itself is a game of chance that should be embraced. The sentiment is mirrored in the famous chorus of Like a Rolling Stone: …How does it feel to be on your own/ Like a complete unknown… In both cases, Dylan celebrates the notion that, for his generation, because of the perceived insanity of the social and political situations they were trapped in, it was necessary to embrace the notion of chaotic chance in order to break away from conventional attitudes and lifestyles.

The next couplet presents another symbolic figure. We hear that …The empty handed painter from your streets/ Is drawing crazy patterns on your sheets… On a surface level, this suggests that ‘Baby Blue’ is in contact with the bohemian world of penniless artists. The phrase ‘empty handed painter’ is, like the ‘orphan’ in the previous verse, an image of futility. How can the painter paint if he is ‘empty handed’? The reference to ‘sheets’ seems to suggest that the ‘painter’ is her ex-lover (possibly the narrator himself) who has left her in great confusion. She clearly does not understand the presumably abstract ‘patterns’ which he is presenting to her. The following line …The sky too is folding under you…with its highly emphasised rhymes, is a surreal image further suggesting that Baby Blue’s world is falling apart. Her worldview seems to be characterised by a kind of hallucinatory intensity. Yet the song never sounds negative, despite its apparently pessimistic chorus. Baby Blue’s universe may be collapsing but this may merely open up a portal to a new way of thinking.

In the third verse the imagery becomes even stranger and more open ended. We first hear that …All your seasick sailors are rowing home… The alliterative and apparently contradictory term ‘seasick sailors’ suggests that the elements in Baby Blue’s life that she normally utilises to maintain her equilibrium are slipping away. This is followed by the bizarre …All your reindeer armies are going home… This phrase appears in all the versions of the song except the official recording on Bringing it All Back Home where Dylan sings ‘empty handed armies’ – clearly an error ass the same phrase appears in the previous verse. Oddly this was not corrected. He sings ‘reindeer armies’ in all the live versions. The phrase ‘reindeer armies’ appears to refer to a group of indigenous Soviet fighters from the north of Siberia who, using reindeer for carriage and sustenance, played a significant part in the fighting against Germany in World War Two. In this case the phrase suggests a very picturesque image of a group of people – who may represent or protect Baby Blue’s security – in retreat. Thus another one of her layers of protection has been removed.

The following couplet…Your lover who just walked out the door/ Has taken all his blankets from the floor… is a more straight forward image of desertion, with the removal of the blankets strongly suggesting that this step is a permanent one. …The carpet too is moving under you… strongly echoes the line about ‘the sky’ from the second verse and is cleverly connected to the idea of blankets being taken ‘from the floor’, indicating that the foundations are shifting under her feet.

After all these evocations of decay and destruction, the final verse now offers hope. The narrator is now freely offering advice to Baby Blue. …Leave your stepping stones behind… he tells her …something calls for you… The image of ‘stepping stones’ (another alliterative phrase) is a remarkable visualisation of the message the narrator is now conveying. They clearly represent her past life. When crossing a river or stream using stepping stones, one rarely looks back as this might disturb the precarious balance one has established. The image also suggests that the journey that Baby Blue is about to go on is not an easy one. This is followed by the rather haunting …Forget the dead you’ve left, they will not follow you… The narrator seems to be imploring Baby Blue to cast off elements of the historical and cultural contexts she has been brought up with, and which have held her back from making progress. He implores her to cast off her insecurities and step forward across those perilous stepping stones into a new life.

The couplet which follows presents another very distinctive and resonant image: …The vagabond who’s rapping at your door/ Is standing in the clothes that you once wore… The couplet includes a brief reference to Poe’s The Raven, which is heard ‘rapping’ at a chamber door. The slightly archaic term ‘vagabond’ conveys an image of a ragged wanderer, dressed here in her ‘hand me downs’. This symbolises the fact that he has left her because of her lack of courage in throwing off the ‘clothing’ of ideas and customs that have held her back. The image also shows the ‘vagabond’ (who may be identified with the orphan, the painter and the lover from previous verses), presenting her with a kind of ‘mirror image’ of herself. It implies that this is how she would look if she had followed his path. Finally he tells her to …Strike another match, go start anew… an effective evocation of the new life she may, if she follows his advice, be starting on very soon.

It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue is one of the outstanding examples of the use of symbolism in Dylan’s work. It makes sense on several distinct levels. It is the cry of a departing lover to his love, appealing to her to accept the fact that he is leaving her. The song also works as an invocation to an individual to step out of a conventional existence, to accept the random nature of life and to take risks in accepting that ‘the highway is for gamblers’. Baby Blue is being urged to have faith in her own potential and trust in providence to save her. The song can thus be seen, like Like a Rolling Stone, to have a strong generational resonance. The ‘stepping stones’ that Baby Blue needs to complete her journey on may be slippery, but they lead to a wholly different viewpoint on life free of the repression of conventional culture.

On another level, the song can be seen as Dylan’s message to himself – which was especially relevant as he was then engaged in a highly controversial musical and personal transition, from ‘protest singer’ to visionary poet and counter cultural avatar. Equally, the song could be seen as being directed at those ‘fans’ who rejected his change in style. This possible interpretation was thrown into considerable relief at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965 when, after delivering his historic three song ‘electric’ set Dylan returned to the stage with his acoustic guitar to confront a partly hostile audience. After a crowd pleasing Mr. Tambourine Man he finished his set with a withering version of Baby Blue which appeared to be directed at the disbelieving crowd. The crowd responded enthusiastically, obviously pleased to hear what many regarded as ‘the real Bob Dylan’. How many of them understood the ironic significance of the song is open to question.

DAILY DYLAN NEWS at the wonderful EXPECTING RAIN

THE BOB DYLAN PROJECT- COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

Leave a Reply