…Do not go gentle into that good night,

Rage, rage, against the dying of the light…

Dylan Thomas, Do Not Go Gentle Into that Good Night, 1952

…What immortal hand or eye

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry…

William Blake, The Tyger 1794

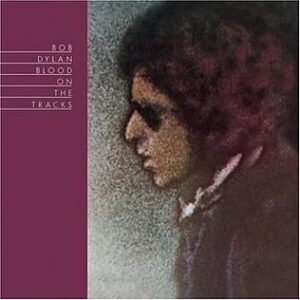

On its release, Blood on the Tracks was acclaimed as Bob Dylan’s first ‘comeback album’. It was clear to fans and critics that the album represented Dylan’s attempt to re-conjure the complex symbolic poetry and the verbal magic of his ‘classic years’ of the mid-1960s. He had apparently suddenly ‘woken up’ from the pastoral dream world of New Morning (1970) and the nostalgic recollections of much of 1974’s Planet Waves. Like the other songs on the album, Idiot Wind has always been linked to the breakup of Dylan’s marriage and the end of his ‘rural retreat’ in the mid-70s. This is not to imply that the songs on the album are directly ‘about’ Sara, as in song that named her explicitly on Desire. In fact the songs examine the vagaries of love from a number of varying viewpoints. But it does seem that the artistic transformation presented on the album was a very difficult and often gut-wrenching process, which may well have involved Dylan recognising that, for him, domestic contentment and full artistic expression were incompatible. The painful realisation of this dilemma is central to the songs of Blood on the Tracks, and of Idiot Wind in particular.

The performance style and presentation of the songs on the album is, however, very different to that of Dylan’s early and mid-60s output. His singing on his releases from John Wesley Harding to Planet Waves had been greatly modified from the abrasive tones of his earlier work towards a softer, more conventional style. On his albums of the late ‘70s and ‘80s his vocals tend to combine the qualities of both periods. The confrontational voice of his early career, which forced listeners to focus on the words of the songs, has now been adapted to a more mature and reflective form of expression. Similarly, the lyricism of Blood on the Tracks combines the symbolist poetry of his earlier work with the more colloquial ‘plain speak’ of his ‘rural retreat’ albums. Much of his 1960s material had been the product of Dylan having ‘tuned in’, perhaps unconsciously, to a poetic muse that had allowed him to produce those unforgettable ‘chains of flashing images’. But now, after years of taking a more relaxed attitude to his work, he has to force himself to (as he put it at the time) …do consciously what he used to do unconsciously… In order to achieve this, he draws on the imagistic techniques of modern art and the storytelling methods of cinema, which are now added to his encyclopaedic knowledge of the Western literary canon and the folk, rock, country and blues traditions.

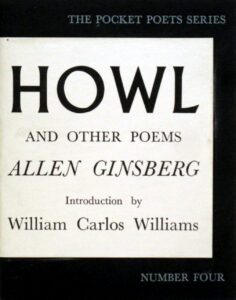

In Idiot Wind, Dylan combines all these methodologies and influences in a new way. As with Tangled Up in Blue and Simple Twist of Fate, various symbolic images are shown from a range of different visual perspectives and the story within the song is not told in a chronological order. It builds up as a series of impressions, using flashbacks and ‘flash forwards’ in the manner of experimental cinema. As the song develops through a series of distinct stages, it steps into what might be called ‘dangerous territory’ until it becomes (in the manner of Allen Ginsberg’s great epic poem Howl) a cry of rage against both personal limitations and, to some extent, those of the wider society. However, Dylan’s narrator goes further than Ginsberg’s Buddhist-influenced diatribe, which may express anger but is grounded in a basically gentle, humanitarian philosophy. Dylan allows his narrator to express what might be called ‘forbidden’ feelings. While other songs on the album (except perhaps for the desperate You’re a Big Girl Now and If You See Her Say Hello) maintain a certain distance from the unfolding action, Idiot Wind distils all its themes in a highly expressive if sometimes chaotic mixture of raw emotion and wide ranging symbolism.

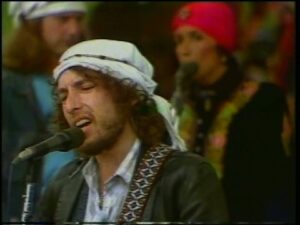

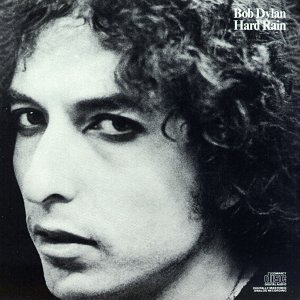

Many of the other tracks involve the use, sometimes interchangeably, of both first person and third person narratives. As demonstrated in the almost brutally raw version which appears on the live Hard Rain album of 1976, Idiot Wind presents a continuous ‘I’ voice which conveys a whole gamut of ‘uncensored’ raw emotion ranging from sadness and nostalgia to intense anger and the desire for revenge. It has always been a very difficult song to sing as it involves the expression of intense, cathartic and sometimes conflicting emotions. Despite being one of Dylan’s most celebrated songs its performing history has been surprisingly limited. Apart from its regular slot on the 1992 tour, it has since been ignored since the days of the Rolling Thunder Revue. On the album and in subsequent live shows, Dylan presents an unprecedented and sometimes almost overwhelming outpouring of great bitterness and regret which he may have found very difficult to replicate in later years.

As the full record of the album sessions which has been now been released on the Bootleg Series’ More Blood, More Tracks reveals, there are considerable lyrical and musical differences between the acoustically-based recordings of the songs from sessions in New York and their later ‘beefed up’ adaptations in a studio in Minneapolis. Although the later version of Idiot Wind retains most of the original lyrics, it could be argued that the ‘New York’ and ‘Minneapolis’ recordings are really two different songs. In the ‘New York’ sessions, the song is first played completely acoustically. The addition of bassist Tony Brown and an especially effective overdubbed organ part from Paul Griffin adds a highly moving melancholic texture to what was originally intended to be the definitive take. This is the version which was featured in 1991 on the initial Bootleg Series release. The ‘New York’ recording uses a full band. The differences are not only of instrumentation, however, but of overall tone and vocal stylings. On the earlier versions, the main emotions being conveyed are those of sadness, regret and confusion. The level of emotional honesty on display is often heartbreaking. The ‘Minneapolis’ version expresses disturbing feelings of frustration, anger and antagonism which build up towards a dynamic and ecstatic declaration of freedom from the constraints of expression which had limited Dylan’s work for several years.

The song’s overall structure remains constant in the different versions. There are eight verses, punctuated by four varying choruses. Each verse has five lines; the first four of which follow a repeated AABB pattern followed by a non-rhyming line, that comments on the rest of the verse (somewhat in the manner of a ‘talkin’ blues’ song) and which forms a half-rhyme with the final line of the succeeding verse. The first two verses, whose lyrics are essentially identical in all the versions, begin fairly abruptly. The acoustic takes have a short strummed intro, while in the released version Dylan begins singing immediately. Each verse begins with relatively short lines, followed by what are often tongue twisting configurations as the narrator becomes more emotional, as if he is somehow trying to cram almost inexpressible thoughts into the established rhythmic pattern. In the next sets of four lines those emotions are allowed to reach their natural conclusions, whether pleasant or unpleasant, sad or vituperative.

The opening declarations thrust us directly into the emotional turmoil that is to follow, as an apparently paranoid narrator begins by telling us, in no uncertain terms …Someone’s got in in for me, they’re planting stories in the press/ Whatever it is I wish they’d cut it out quick – When they will I can only guess… This immediately alerts the listener to the possibility that the colloquial, apparently revealing, narrative voice may be Dylan’s own; especially given his well known antipathy towards the mass media’s treatment of him as a celebrity and his career-long attempts to protect his private life. But this is mysteriously undercut by the seemingly random detail of …They say I shot a man named Gray and took his wife to Italy/ She inherited a million bucks and when she died it came to me… followed by the apparently ironic disavowal of …I can’t help it if I’m lucky… On the Minneapolis version Dylan sounds defiant and cynical, whereas in the New York recording he is despairing, almost helpless. It does seem, however, that he may be exaggerating or satirising the distorted views of his life which the more sensational tabloids had often printed. The final denial seems to be a particularly barbed riposte to such distortions, although Dylan’s tongue in cheek account has already blurred the line between fiction and reality. There will, however, be no more mentions of the mysterious ‘Mr. Gray’ or the storyline associated with him in the song.

The next lines, however, are apparently even more personal as the narrator first makes a general complaint and then addresses a yet unknown figure who we may assume is either a lover or an intimate friend …People see me all the time and they just can’t remember how to act/ Their minds are full of big ideas, images and distorted facts… appears to give us Dylan’s own voice again, expressing his frustration and annoyance at having been labelled a ‘prophet’ or ‘the voice of his generation’ and graphically showing how being categorised in this way affects his personal relationships. He sounds even more exasperated as he declares …Even you, yesterday, you had to ask me “Where it was at”/ I couldn’t believe that after all these years you didn’t know me any better than that… ending with another ironic address: …Sweet lady… From the first two verses it seems as if the song will consist of a general complaint about the way Dylan’s personal life (and by implication, his ability to be a creative artist) has been compromised by the public perception of him as a seer or genius that he has had to live with from a remarkably young age. Even his lover appears to treat him as some kind of fount of wisdom. But this will only be the starting point for the song – a kind of introduction to or a contextualisation of his personal struggle to remain creative within a world in which any popular artist is immediately labelled or categorised by the media in a very limiting way.

Who, we may ask, is that ‘sweet lady’? It has been reported that the phrase ‘idiot wind’ was a favourite of Dylan’s painting teacher Norman Raeburn, who seemingly contributed greatly towards Dylan’s new ‘conscious’ writing methods. The phrase seems to have been used by Raeburn to describe an internal process by which an artist can place ‘idiotic’ limitations on his work by fearing to transgress established conventions. But this is a limitation in itself, which Dylan seems determined to overcome. He takes his teacher’s phrase and twists its meaning around.

In the first chorus Dylan uses the refrain to place his initial complaint in a wider context: …Idiot wind, blowing every time you move your mouth/ Blowin’ down the back roads to the south… suggests that the ‘wind’ is actually a metaphor for the way individuals express themselves – what might be called the ‘breath of life’. The reference to the ‘back roads of the south’ seems to suggest that this wind also ‘blows’ across the entire continent, especially the troubled south with its history of racial conflict and suppression. Dylan then switches from the general to the acutely personal: …Idiot wind, blowing very time you move your teeth… We now hear the whistle of the ‘wind’ as it emerges from an individual’s mouth. This is followed by what appears to be a rather vicious ‘put down’ of a lover: …You’re an idiot babe/ It’s a wonder that you still know how to breathe… This (quite literally) tongue twisting refrain will be repeated in the next two choruses. But whether it is being addressed to a lover, to the singer’s audience, to those in the media who have plagued him or to himself, remains open to question.

The narrator then begins to wax lyrical about the role of fate or chance in his life. In the New York version he begins with a confession that …I threw the I-Ching yesterday, it said there’d be some thunder at the well… This sounds perhaps a little menacing, although it actually implies that he has thrown Hexagram 51, which can often generate quite a positive reading. But the narrator contrasts this with the rather tortured and despairing…I haven’t known peace and quiet for so long, it feels like living hell… In the revised version, the Chinese oracle is replaced by a rather less esoteric ‘fortune teller’ who warns, rather more dramatically, of ‘lightning that might strike’. The second line now becomes the even more despairing: …I haven’t known peace and quiet for so long, I can’t remember what it’s like…

We then begin to move away from the personal angle towards more symbolic imagery. In the acoustic version we are told …There’s a lone soldier on the hill, watching falling raindrops pour/ You’d never know it to look at him, but in the final end he won the war/ After losing every battle… This shift appears to indicate that the narrator suddenly sees himself from a different perspective – as if he is a figure in a Picasso painting – with the implication being that he himself is the ‘lone soldier’, struggling to assert himself but ultimately assured of ‘victory’ over his detractors and his own ‘writer’s block’. In the ‘official’ version we are taken more explicitly into the realm of symbolist poetry as the lines become …There’s a lone soldier on the cross, smoke coming out of a box car door/ You didn’t know it, you didn’t think it could be done, but in the final end he won the wars/ After losing every battle… These lyrics are more powerfully suggestive. The ‘lone soldier’ is now not merely passively overlooking the scene. He is, it seems, being ‘crucified’, as the media are wont to do to public figures who they wish to ‘bring down’. The remarkable image of the ‘smoking box car’ evokes memories of Woody Guthrie’s travels in Bound for Glory, while simultaneously suggesting some kind of fiery conflagration. There is also more of a direct address in the second line here, with the narrator defying his detractors for their lack of belief in him.

The tone of defiance continues in the next verse as the narrator proclaims …I woke up on the roadside, daydreaming about the way things sometimes are…. There is a suggestion that the visions of the ‘lone soldier on the cross’ and the ‘smoking boxcar’ have been part of the narrator’s dream. The next line …Visions of your chestnut mare shoot through my head and are making me see stars… appears to take us back into that dreamland. The reference to the ‘chestnut mare’ seems to be an allusion to the hit song of that name by The Byrds, co-written by Roger McGuinn and Jacques Levy, in which the eponymous creature is clearly symbolic of a woman. This supplanted the New York recording’s similarly horse-oriented …hoof beats pounding through my head at breakneck speed… Both images give the dreamy impression that the narrator is being transported from the scene on horseback. But this dreaminess gives way to the song’s most vicious putdown: …You hurt the ones that I love best and cover up the truth with lies/ One day you’ll be in the ditch, flies buzzing around your eyes… In the live ’76 version the ‘mare’ is replaced by a ‘smoking tomb’, and the ‘ditch’ by a grave. These lines appear to gel more with the following chorus: …Idiot wind, blowing through the flowers on your tomb, Idiot wind, blowing through the curtains in your room…

The narrator seems to be wishing for a grisly end for the subject of the song. But by now we must surely be questioning whether he is really addressing a lover. Perhaps, as in many blues songs, the reference to a ‘babe’ is merely an ironic device. The ‘you’ in the choruses is not necessarily the same person as the ‘you’ in the first verse. In fact, it is the ‘idiot wind’ itself – the wind of hypocrisy, corruption and lies that seems to swirl around the narrator – which, in personified form, is being addressed. From now on, the narrator, having gathered inner strength from making these declarations, will not hold back in his condemnation of ‘The Wind’.

The next verse is fairly restrained compared with what will follow. The narrator begins with …It was gravity which pulled us down and destiny which broke us apart… which suggests that in the past he had been ‘in league’ with The Wind – which here may symbolise the need for poets to confront their inner demons. The narrator then becomes accusatory: …You tamed the lion in my cage but it just wasn’t enough to change my heart… as if The Wind has been a dampening force, restraining his poetic expression and containing his powerful and potentially violent feelings. Like Blake’s Tyger, Dylan’s ‘Lion’ is neither good nor bad, but represents an energetic inner force which The Wind has restrained. Because of this the narrator’s view of the world has been distorted and his judgement has been corrupted: …Now everything’s a little upside down, as a matter of fact the wheels have stopped/ What’s good is bad, what’s bad is good, you’ll find out when you reach the top… Then Dylan sneers …You’re on the bottom… It seems that the narrator’s ‘inner lion’ has not really been ‘tamed’ at all. Now he seems determined to fight his way out of the ‘cage’. He is ready for the fight. …I noticed at the ceremony… he tells us …your corrupt ways had finally made you blind…. He even rejects the veracity of his own memories: …I can’t remember your face any more, your eyes don’t look into mine…

We now retreat into the narrator’s visions as we are regaled with more extraordinary imagery. We hear that …The priest wore black on the seventh day and sat stone faced while the building burned/ I waited for you on the running boards, near the cypress trees, while the springtime turned/ Slowly into autumn… In the narrator’s dream world The Wind manifests itself as a stern faced priest who – presumably because it is the Sabbath – refuses to help others. Then we are back in the 1930s or 40s, when running boards were common on vehicles. The term was also used for boards that were placed on top of box cars in order that brakemen could operate hand-controlled brakes, linking the image to that of the box car in the previous verse. Cypress trees were symbols of mourning in the ancient world. It is as if the narrator is picturing himself in an ultra slow motion film, in a world in which the Idiot Wind has been blowing through all time. Dylan stretches out the pronunciation of ‘slowly’ to emphasise the fact that he is imagining time almost coming to a halt.

CYPRESS TREES

The first lines of the next chorus are used – in a brilliantly imaginative tour de force – to stretch the meaning and significance of The Wind to encompass the corruption within American politics which had recently been exposed in the Watergate scandal, while the narrator imagines the wind circling around himself, threatening to carry him away: …Idiot wind, blowin’ like a circle around my skull/ From the Grand Coulee Dam to the Capitol… The mention of the Grand Coulee Dam – a huge engineering project to dam the massive Columbia River in Washington State – again evokes Guthrie, who wrote a song celebrating the achievement which Dylan himself covered at a Tribute show in 1968. The Wind is now shown to encompass the whole of the country, from Washington State to Washington D.C. – both places, of course, named after the founder of American democracy and its first President. We are now ready for what will be, quite literally, a glorious climax to the song.

CAPITOL BUILDING, WASHINGTON

The original lines from the acoustic version are, however, considerably milder (and almost apologetic) in tone: …We pushed each other a little too far and one day it just turned into a raging storm… Meanwhile …The hound dog bayed beyond your trees as I was packing up my uniform… The imagery here is a little vague. Despite the reference to a ‘raging storm’, the narrator sounds despairing and rather hopeless as he conducts an internal dialogue: …Well, I figured I’d lost you anyway – Why go on? What’s the use? In order to get in a word with you I’d have had to come up with some excuse/ And it just struck me kind of funny… Finally he sounds rather beaten and battered, not to mention resentful: …I’ve been double crossed too much, at times I think I’ve almost lost my mind/ Ladykillers load dice on me, while imitators steal me blind…The closing lines, though quite powerful in their own way, merely compound the tone of resignation: …You close your eyes and pout your lips and slip your fingers from your glove/ You can have the best there is but it’s gonna cost you all your love/ You won’t get it for money…. The Wind is personified here as a domineering woman who has now got him entirely under her control. The final chorus : …Idiot wind, blowing through the buttons of our coats/ Blowing through the letters that we wrote/ Idiot wind, blowing through the dust upon our shelves/ We are idiots, babe, it’s a wonder we can even feed ourselves… depicts the narrator trapped in a destructive relationship with his muse, and seeing no way out of the situation. The song then trails off into the distance, with the swirling organ sounds adding to the pathos. In this version, the narrator has settled for an uneasy relationship with The Wind. Both participants have lost the strength they had when joined together.

In the Minneapolis version the final verses are considerably rewritten, with the full band sound carrying a much stronger and more defiant message as the music swells to a dramatic climax. Instead of surrendering himself to The Wind, the narrator confronts it (or ‘her’) head on. When he sings …I can’t feel you anymore, I can’t even touch the books you’ve read… Dylan may be referring to his own detachment over the past few years from the literary education that had been so vital to him. He depicts the lack of inspiration he had been suffering from in a highly graphic way: …Every time I crawled past your door… he snarls …I been wishin’ I was somebody else instead… But then he appears to take a deep breath and, summoning up his full poetic powers, delivers a quite magnificent collocation of imagery: :…Down the highway, down the tracks, down the road to ecstasy/ I followed you beneath the stars, hounded by your memory/ And all your raging glory… On first listen the word ‘hounded’ might sound like ‘haunted’ but ‘hounded’ is certainly more original and powerful. The rather generic blues image of the ‘hound dog’ from the earlier version is now transformed into a beast that has been snapping at his heels and will not let go. This is a memory that he cannot – and indeed, should not – forget. In order to regain his full poetic powers, the narrator must tame The Wind by breathing it in deeply and then exhaling it. The Wind may have followed him, even tormented him, but ultimately it allows him to create the ‘glorious’ forms of expression that he now gives full rein to.

In the final verse Dylan delivers his defiant cry of liberation. Cramming in the syllables as if motivated by the power of The Wind, he declares that …I’ve been double crossed now for the very last time and now I’m finally free!…. and then, in perhaps the song’s most resonant image of all, cries …I kissed goodbye the howling beast on the borderline that separated you from me…. Now the ‘lion’ from the previous verse is completely uncaged. There is no longer a separation between the narrator and The Wind. He now recognises that The Wind is actually a vital part of himself that he will need to become integrated with.

As we now hear, the result is the restoration of his poetic voice, in all its ‘raging glory’. But there is still a final admonition to come as the narrator tells The Wind that …You’ll never know the hurt I suffered or the pain I rise above/ And I’ll never know the same about you, your holiness or your kind of love/ And it makes me feel so sorry…. He may have reconnected with his expressive soul’s ‘holiness’ and ‘kind of love’ but he realises that he will never really understand the mysterious process of creation that crossing the borderline entails. Therefore, the implication is that the border controls could be re-erected at any time, so that his new found inspiration could be lost. This tempers the triumphant tone that he has now adopted. The concluding chorus is unchanged in terms of lyrics from the original version but it is now delivered as a howl of rage rather than a beaten cry of surrender.

In Idiot Wind Dylan attempts to come to terms with the process of ‘doing consciously what he had once done unconsciously’. He now realises that The Wind may be a cruel and destruction force but that it also contains a vital energy, like that of Blake’s Tyger, that needs to be harnessed. In the poignant acoustic version the narrator seems to have accepted that The Wind will always control him. But in the revised and ‘super charged’ rerecording of the song Dylan seems to have realised that only through confronting his own inner demons by expressing great rage can he regain his full creative powers. Both versions of the song communicate the painful truth that in order to continue to reach such poetic heights, he will have to work much harder than he did when he was younger. Ultimately, although Idiot Wind may be a fearless confrontation of the inner pain of losing inspiration, it is also a sobering reminder that, as we age, we need to continually examine our selves in order to stay in touch with our inner life force. On Blood on the Tracks, and most especially on Idiot Wind, Dylan confronts this problem with great courage and resolution. Having achieved so much at such a young age can be a considerable burden, and was especially so for one who had been acclaimed as ‘the voice of a generation’. But Dylan is clearly determined to continue to evolve as a poet and a song writer. In Idiot Wind he demonstrates with great eloquence that he is completely committed to continuing the struggle.

THE CAMBRIDGE BOB DYLAN SOCIETY

Leave a Reply