No place, not even a wild place, is a place until it has had that human attention that at its highest reach we call poetry.

–Wallace Stegner, The Sense of Place (1989)

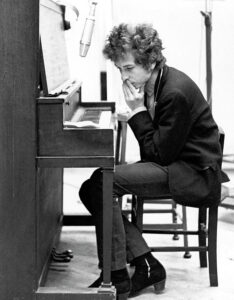

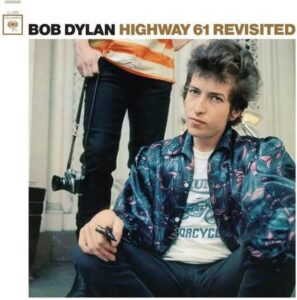

Highway 61, the main thoroughfare of the country blues, begins about where I began. I always felt like I’d started on it, always had been on it and could go anywhere, even down in to the deep Delta country. It was the same road, full of the same contradictions, the same one-horse towns, the same spiritual ancestors … It was my place in the universe, always felt like it was in my blood…

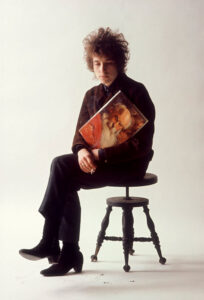

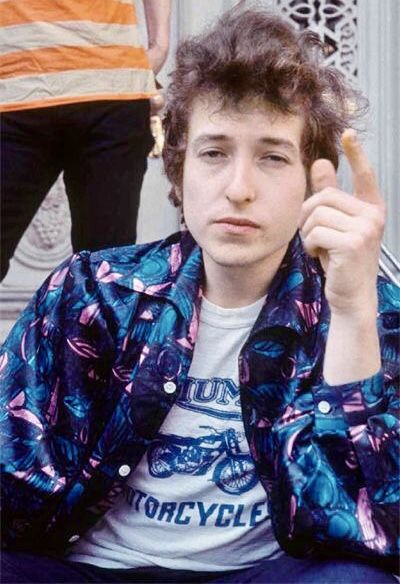

Bob Dylan, Chronicles Vol. One (2003)

In his seminal work of literary criticism Studies in Classic American Literature (1923), the great novelist D.H. Lawrence (focusing mainly on authors like Whitman, Melville and Hawthorne) argued that what differentiates American from European literature is what he called ‘the spirit of place’. The tradition of poetically naming particular locations, which Whitman in particular followed at great length, has meant that many towns, cities, beaches, lakes and even roads in the USA sound strangely familiar. A British person travelling through California, for example, may find themselves constantly distracted by the place names they may read on road signs. Names like ‘San Jose’, ‘San Francisco’, ‘LA’ ‘Pasadena’, ‘Ventura’, ‘Monterey’, ‘Compton’, ‘Mohave’ and ‘Joshua Tree’ all have strong associations with well known songs, books or movies.

The United States is such a large country, and has so many regional variations in terms of geography, industry and social organisation that American art forms of all kinds have always needed to focus on particular locations, as well as on the means of travel between them. A direct line could be drawn between Huckleberry Finn and On the Road, both of which romanticise the very act of travelling across the country, which becomes in itself as much an inner as a physical journey. By travelling through ‘States’ (of mind) the protagonists discover themselves. Lawrence’s observation remains just as valid today as it did a century ago.

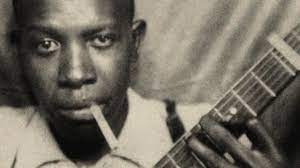

In no other American art form is this truer than the blues, especially during its heyday in the early twentieth century. The blues originated in the American Deep South but the most prominent area associated with it was the so-called ‘Mississippi Delta’. Among the musicians who came from this area were Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker, Son House, Big Joe Williams, Howlin’ Wolf, Sonny Boy Williamson and Charley Patton. In early blues songs, names of towns such as ‘Clarksdale’, ‘Vicksburg’ and ‘Tupelo’ crop up frequently. The singers rarely got the chance to record, and even if they did they were unlikely to be well rewarded. Thus in order to find audiences they tended to adopt a travelling lifestyle, even if they could often not afford train fares and had to travel in box cars or by hitch hiking.

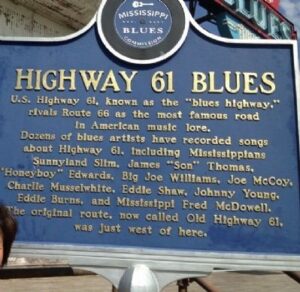

Many blues songs, such as Sippie Wallace’s Mail Train Blues (1926), Big Bill Broonzy’s Too Too Train Blues and Leadbelly’s much covered Midnight Special (1934), use railway journeys as a focus. Other songs, such as Howlin’ Wolf’s Highway 49 Blues (1935) and Curtis Jones’ Highway 51 1938) feature the names of prominent American highways, especially those which connect to the Deep South. Dylan covers Highway 51 on his debut album. Most of these songs feature the singers threatening to ‘hit the highway’ if their woman leaves them, or bemoaning the fact that their lovers have already done so. Highways could represent escape from poverty or the consequences of crime or broken relationships. There are number of songs about Highway 61, most notably Highway 61 Blues, first recorded by Roosevelt Sykes in 1932 and 61 Highway Blues by Mississippi Fred McDowell (1959). By the time of McDowell’s recording the highway had featured in so many songs that it had begun to take on mythic connotations. It was at the intersection of Highways 61 and 49 that Robert Johnson supposedly sold his soul to the Devil.

ROBERT JOHNSON

The road itself is 1,400 miles long and runs from New Orleans – the ‘birthplace of the blues’ – up to Dylan’s home state of Minnesota. It also follows of the course of the USA’s longest river, the Mississippi, which itself occupies a prominent place in American literature and folklore. When the Great Depression hit the country in the 1930s, many black people migrated north towards the cities of Chicago and Detroit, in search of work and a better life. It was in these northern cities that blues musicians began the experimentation with electric instruments that led to the creation of the electric blues format and ultimately to the all-conquering genre of rock and roll. Thus Highway 61 embodies the twentieth century history of black people in America.

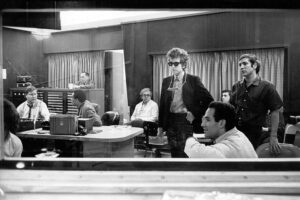

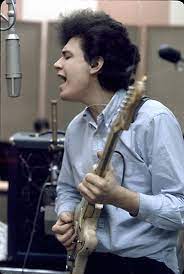

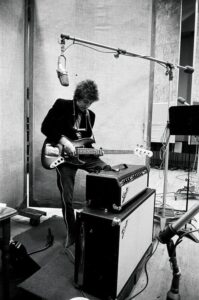

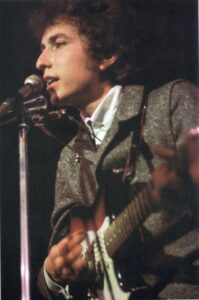

When Dylan famously ‘went electric’ at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965 he was backed by members of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, whose extraordinarily talented guitarist Mike Bloomfield ’s guitar playing greatly enhanced the Highway 61 album. Bloomfield was one of the key figures in this musical evolution, demonstrating the potential of the electric guitar to ‘speak’ as the loudest voice in the rock revolution. The blues became the foundation for leading post-Beatles American rock bands such as The Doors, The Allman Brothers Band and Canned Heat (as well as British musicians like The Rolling Stones, The Animals, The Yardbirds, Fleetwood Mac, Led Zeppelin and Eric Clapton); later mutating into the psychedelic styles of Jimi Hendrix and The Grateful Dead.

BOB DYLAN AND MIKE BLOOMFIELD

Highway 61 Revisited song follows a rigid twelve bar blues structure, although the speed and intensity of the playing on the original recording creates what was then a very modern sound. Dylan engages the audience with a series of witty exchanges, with the words ‘Highway 61’ appearing at the end of each verse. In many live versions of the song by Dylan and others, each repetition of these words triggers off a chance for the guitarist to take up Bloomfield’s mantle and fire off explosive solos. The song has become one of Dylan’s ‘rock standards’ and has been recorded by Johnny Winter, Bonnie Raitt, Billy Joel, Dave Alvin, John Mellencamp, Terry Reid, Dr. Feelgood and many others. Bruce Springsteen has played Highway 61 live on a number of occasions and duetted with Dylan on the song in New York in 2003. Most of these artists treat the song as straight blues rock, although P.J. Harvey’s ‘primitive’ version (1993) channels it through a post-punk sensibility. Dylan himself has performed the song on thousands of occasions throughout his career, rarely altering its basic structure or lyrics.

Dylan trades on the mythic, historical, literary and musical significance of the road to produce a devastating satire on the rampant materialism and violent nature of American culture. Each of the five verses features two characters and many of the lines consist of dialogue spoken between them. Dylan introduces national, quasi-religious and mythical themes but the song is essentially playfully provocative. Whereas the riveting It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding), another blues-based song, had covered this territory philosophically, in Highway 61 he delights in the sheer comic effect of the dialogues he sets up. Much of this is achieved by the use of modern colloquial language, perhaps most effectively utilised in the hilariously sacriligious opening verse which presents a hilariously sacrilegious conversation between God and Abraham in ‘hipster jive’.

The conversation is based on the passages in Genesis 22, when God commands Abraham – the patriarch of the Jewish nation – to kill his son Isaac in order to ‘prove his faith’. Although God eventually relents, Abraham is fully prepared to follow the instructions. This famous Biblical story has been referenced in many stories and poems. In The Parable of the Old Man and the Young (1918), Wilfred Owen uses the story as an image of the horrors of World War One. The poem ends:..But the old man would not so, but slew his son/ And half the seed of Europe, one by one…. Later, in the mournful Story of Isaac (1968), Leonard Cohen relates the story to the slaughter then going on in contemporary wars. Dylan characterises the God of the Old Testament as cruel and threatening, almost as if He is some kind of gangster. The lines are delivered with great economy, as the verses build from relatively calm openings to manic conclusions …God said to Abraham… Dylan begins …Kill me a son!…

The response is pure ‘hip speak’: …Abe said “Man, you must be puttin’ me on… Here the Biblical patriarch becomes ‘Abe’. He has the temerity to address Jehovah as ‘man’. Immediately Dylan deconstructs the famous Biblical story. By putting it into modern language there is an immediate suggestion that this is happening now, rather than in some ancient era. The next lines make remarkable use of staccato bursts of speech: … God said, “No” Abe said, “What?”/ God said, “You can do what you want, Abe…” which move the song forward in awkward rhythmic jerks which mirror the tension that already exists in the song. Jehovah here is hardly a ‘God of love’ here and we can guess that a threat is coming. And so it is: …But next time you see me coming… God tells him …You better run!… ‘Abe’ then gives in to this barely veiled warning before God tells him that the murder must be enacted on Highway 61. In these few lines, which pointedly do not mention any contemporary wars, Dylan posits the God that so many Americans follow as a God of war and destruction, the murderer of children. In the context of the then-expanding American involvement in the fight against ‘Godless communism’ in Vietnam, with all its attendant atrocities, this is especially pertinent. Yet Dylan, unlike Owen and Cohen, uses devastating black humour to illustrate his point.

The second verse consists of a conversation between two figures from blues mythology, Georgia Sam and Poor Howard. Georgia Sam is the subject of Anna Lee Chisholm’s Georgia Sam Blues (1924) and Poor Howard is the protagonist of Leadbelly’s Poor Howard/Green Corn (1939). Both figures are of dubious virtue. Georgia Sam has abandons his lover while Poor Howard murders his wife. He is thus a dubious character to ask for advice. Again the context is modernised. We hear that the ‘welfare department’ will not help Sam out of his predicament, which presumably is one of extreme poverty. The gun wielding Poor Howard ‘points with his gun’ towards Highway 61, which (as with so many poor blacks in the South) is Sam’s only escape route. Again the language is crisp and modern. Sam addresses Howard as ‘man’: …Tell me quick, man, I gotta run… The suggestion is that Sam has committed some kind of heinous crime.

Dylan’s lyrical inventiveness is something to behold here. In the next verse we get two more ‘colourful’ characters, ‘Mack the Finger’ and ‘Louie the King’, who appear to be two American hucksters. ‘Mack the Finger’ seems to be a comical variation on the famous ‘Mack the Knife’, a character in Bertolt Brecht’s Threepenny Opera (1929) originally based on Macheath, amn eighteenth century highwayman. The Ballad of Mack the Knife, with lyrics by Brecht and music by Kurt Weill, was memorably recorded by Louis Armstrong, who had one of his biggest hits with the song in 1955. If anything, ‘Mac the Finger’ sounds even more sinister. ‘Louie the King’ is a con man in Huckleberry Finn who, somewhat absurdly, claims to be the disposed King of France. In Dylan’s song these two characters seem to represent the seamy side of American capitalism. Mac proclaims to Louie that he has a load of useless produce: …I got forty red, white and blue shoestrings/ And a thousand telephones that don’t ring… The shoe laces are in the colours of the American flag. Louie, however, is not one to pass up a money-making opportunity. …Yes, I think it could be very easily done! … he proclaims, in the voice of a true American ‘entrepeneur’ … Take everything down to Highway 61…

We then move into mythical territory, with Dylan setting up a conversation between two legendary figures, the ‘fifth daughter’ and the ‘first father’. Later we meet the ‘second mother’ and the ‘seventh son’. In the manner of an old folk song like Willie O’Winsbury, the daughter begins by revealing to the father that ….”My complexion”, she said, “is much too white”… presumably indicating that she is pregnant. The father reacts in modern colloquial English by saying …Mmm, you’re right!… and then decides that the ‘second mother’ must be told. However, we soon learn that …the second mother was with the seventh son/ And they were both out on Highway 61… The ‘first father’ is clearly a patriarchal figure, while calling someone a ‘second mother’ is a common term of affection. A ‘seventh son of a seventh son’ is said to have supernatural powers. In Greek mythology, Aglaea, the goddess of good health, is said to have four sisters Hygieia, Panacea, Aceso, and Iaso. There is also a reference to ‘twelfth night’, a festival marking the end of the Christmas holiday. Dylan is clearly enjoying himself here, playing around with the numbers and thus the relationships between this weird family group, who has provided with symbolic names. In this verse, however, their symbolic status is undermined. They provide no solutions to the problem, as half

AGLEA

the family have already taken to the road.

In the final verse, we meet two more hustlers. The ‘Roving Gambler’ is the protagonist of a well known folk song, which Dylan covered in his Greenwich Village days and later on the Never Ending Tour. We learn, rather bizarrely, that he is ‘very bored’ and is therefore …trying to create the next world war… He meets a promoter, who is dubious at first but then is inspired to respond …Yes! I think it can be very easily done/ Just put some bleachers out in the sun/ And have it on Highway 61… So the song ends with a kind of comic apocalypse. The promoter is another representation of the American mind set. Anything, it seems, can be turned to a profit – even, absurdly, the ‘third world war’ – which, just three years after the Cuban Missile Crisis, would be assumed to be as conflagration that would bring about the end of the world. While Dylan once railed against the obscenity of nuclear fallout shelters in Let Me Die in My Footsteps and delivered the astonishing cataclysmic poetry of A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall, he now treats the subject satirically. In doing so he links the extremely capitalistic – and distinctively American – attitude he lampoons in the other verses to the mentality that could potentially cause Armageddon.

Highway 61 Revisited thus marries Dylan’s deep love and respect for the blues with his perception of the insane logic that could lead to universal destruction. It is clear that the Old Testament deity who appears in the first verse will not be able to save us from this fate. Dylan thus transforms the symbolic significance of the highway, using it to make it symbolic of the way that corrupt individuals (or the deities they believe in) – manipulate others. In this song the highway represents not an escape from poverty or deprivation, or from a broken relationship, but from the personal responsibility we all have to preserve decency and humanitarian feelings in a corrupt world. The humour in the song is especially effective as social and political satire. By now he may have concluded that such an approach was the only way to deal with the vicissitudes of a world which was being run on insanely dangerous principles.

Leave a Reply