The shocking immediacy and passionate cynicism of 1974’s Dirge was correctly interpreted by many fans and commentators as a strong indication that the era of Bob Dylan the ‘family man’ was coming to an end. This was particularly striking as it was released on Planet Waves, most of which consisted of much lighter songs about love or his childhood. It is a one off performance. The song was never included in any of Dylan’s live sets. It seems therefore to encapsulate a particular moment in time as he struggles to emerge from several years of writing more relaxed, less challenging songs. The bitterness of its sentiments also anticipates the tone and style of Blood on the Tracks.

In many ways Dirge is presented like one of Dylan’s old protest songs. The six verses use a basic AABB rhyme scheme and a repeated regular rhythm. There are no choruses or refrains. The musical backdrop consists of a remarkable duet between Dylan’s characteristically rhythmic ‘stabbing’ piano and Robbie Robertson’s deft and melodious Spanish style acoustic guitar. At times the two instruments seem to be playing separate tunes. This is particularly effective as the song deals with conflicting emotions. Despite the apparently ‘doomy’ picture it paints, it also appears to offer considerable hope for the future. But the performance appears to signify an acceptance that, for an artist such as Dylan to fulfil his creative potential, inner conflicts cannot be ignored and emotional pain and struggles need to be confronted. A dirge is a traditional form of song which is performed at funerals to honour the dead. The Lyke Wake Dirge from North East England, which was performed by folk groups of 1960s and 70s such as Pentangle, was one famous example. The eloquent sadness of the song makes it a kind of dirge or elegy for his period of domestic bliss and relative obscurity.

Dylan’s narrator appears at first to be addressing a woman he has had a relationship with. As with other songs in which he appears to be directing his love – or his venom – towards a particular woman, many commentators have tried to link this song to his memories of women he was associated with in the mid-1960s, such as Suze Rotolo, Joan Baez, Edie Sedgwick or Nico. But no detailed historical or geographical context is given here. We learn almost nothing about this person in the song or any actual details of a relationship. As in Like a Rolling Stone, Dylan appears to be using the convention of a personal address to articulate his feelings about a particular woman. But the expression of rage in the songstrongly suggests that he has wider concerns about his relationship with fame and his public. Much of the narrator’s bile seems to be being directed not at the woman but at himself. This is apparent in the first line of the song, which is already shocking in its intensity and apparent emotional honesty: …I hate myself for loving you and the weakness that it showed…

The next line, however, seems to be dismissing the ‘lover’ as a superficial and destructive force: …You were just a painted face on a trip down Suicide Road… Perhaps the narrator is addressing the woman in scathing terms. But then the narrative takes us back in time. We are then taken into a mysterious location and a definite denouement is presented to us: …The stage was set, the lights went out all around the old hotel/ I hate myself for loving you and I’m glad the curtain fell… On one level, this could be a metaphorical description of the end of the relationship. However, in the context of this particular moment of Dylan’s career, the reference to the ‘falling curtain’ seems to connect strongly with the fact that the song was written towards the end of an eight year hiatus from touring. Thus it already seems that the ‘lover’ being addressed is a personification of the corruption of the falseness of ‘showbiz’ – just a ‘painted face’. Some commentators have referred to the line about ‘Suicide Road’ to suggest that the song is about the drugs that – in Sara, his semi- autobiographical address to his wife written two years later – he tells us that he had ‘taken the cure’ for. Ironically, he would sing that song onstage hidden behind white face paint. Perhaps the ‘hotel’ referred to here is New York’s Chelsea Hotel, Dylan’s sometime residence in the mid-1960s, which is also referred to in Sara.

BOB DYLAN AND THE BAND LIVE 74

Thus it appears that the song has several targets at once. Dylan throws in elements of his own personal history and mythology in a song which gradually goes deeper and deeper into his own psyche. The lines …I hate that foolish game we played and the need that was expressed/ And the mercy that you showed to me, whoever would have guessed?… strongly suggest that he is conducting an internal discourse with his own conscience. Despite the anger that has been shown so far, the narrator recognises the healing effect of the ‘mercy’ being shown here. He has clearly not followed ‘Suicide Road’ to its logical conclusion. Somehow, his own conscience has saved him. Yet he is clearly recalling a time in which his life was at a low ebb. In what follows, he gives us perhaps the song’s most moving lines, which have an almost Blakean tone: …I went out on Lower Broadway and felt that place within/ That hollow place where martyrs weep and angels play with sin… Lower Broadway is an area of Nashville near the Ryman Auditorium, the ‘home’ of country music. The street has many honky tonks and other music venues. This is a location which Dylan is very likely to have visited during any of his sessions in Nashville from 1966 to 70. Therefore the ‘martyrs’ and ‘angels’ are characters in country songs, such as It Wasn’t God who Made Honky Tonk Angels (originally recorded by in 1952 by Kitty Wells) which certainly deal with the consequences of sin in a big way. Thus Dylan may be giving some explanation for his ‘country music period’. Perhaps more importantly, though, he refers to a ‘hollow place…within’, which is presumably the source of his own creativity as well as his inner pain. This is the pain he will soon need to confront in order to produce Blood on the Tracks.

LOWER BROADWAY, NASHVILLE

Dylan then appears to be addressing himself in his early ‘protest phase’: …Heard your songs of freedom and man forever stripped/ Acting out his folly while his back is being whipped… The ‘slave’ comparison is then made explicit as Dylan laments the parlous state of humanity that led him to write these songs: …Like a slave in orbit he’s beaten ‘till he’s tame/ All for a moment’s glory and it’s a dirty rotten shame…There is genuine anger in his voice here. He appears to be inferring that his own political rage was ‘beaten’ out of him. But he also acknowledges that the world that these ‘songs of freedom’ were written about has not essentially changed. The fourth verse contains perhaps the crucial lines in the song …There are those who worship loneliness, I’m not one of them… seems to suggest that his years of ‘rural retreat’ were necessary but will not be permanent. He is itching to get back into the fray: …In this world of fibreglass… he sings …I’m searching for a gem… He is now challenging his inner self in an attempt to revive the depth of inspiration that he had struggled with during these years. Up to now, though …The crystal ball upon the wall hasn’t showed me nothin’ yet… But he is clearly hoping that the ‘magic’ will happen again. He feels that he has fulfilled his bargain with those ‘weeping angels’: …I’ve paid the price of solitude but at last I’m out of debt…

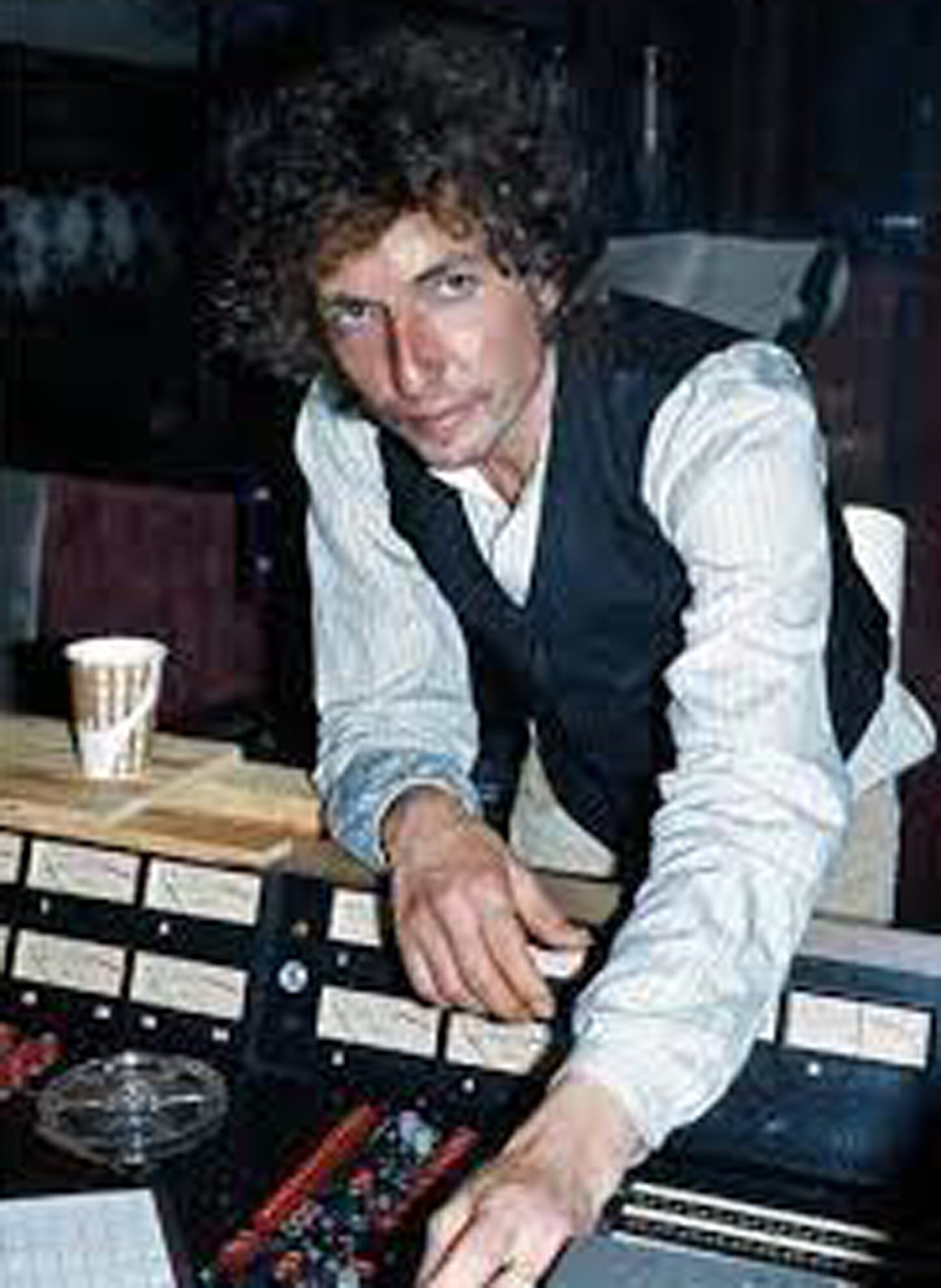

BOB DYLAN IN ‘PLANET WAVES’ SESSION

The narrator then spits out some more venom: …Can’t recall a useful thing you ever did for me/ ‘Cept pat me on the back one time when I was on my knees… Now he appears to be addressing his inner demons again, although he could also be referring to the mass media – an entity for which Dylan has frequentlyexpressed nothing but contempt. Certainly he seems angry at the way he has been treated. He describes a ‘stand off’ between himself and this personification of an individual who he has been lambasting throughout the song: …We stared into each other’seyes ‘till one of us would break/ No use to apologise, what difference would it make?… Despite the pain he has been through, in the final verse he gives us a note of proud defiance, beginning with the most ‘ant-establishment’ lines he has delivered for many years: …So sing your praise of progress and of the Doom Machine/ The naked truth is still taboo wherever it can be seen… In other words, the kinds of injustices and horrors that the younger Dylan had railed against are still there. But right now he is waiting for his ‘crystal ball’ to provide him with the words he needs to point them out. He ends on a fairly hopeful, upbeat note: …Lady Luck, who shines on me, will tell you where I’m at… (a passing reference to Luck Be a Lady, a Frank Sinatra standard) Then he reiterates his opening statement, with a new coda: …I hate myself for loving you… he tells her again, but then becomes more equivocal …But I should get over that…

DYLAN AND THE BAND 74

The song, in which Dylan has displayed such anger and self-loathing, now ends on a more hopeful note. However, the tongue in cheek cynicism of ‘I should get over that’ still conveys a degree of uncertainty. If the song is a dirge, it is announcing the death of one part of Dylan’s career and is looking hopefully towards the future. Planet Waves is something of a patchy album which was rather disappointing for many fans, who were hoping that – after what was, by the standards of those days, such a long hiatus between albums -he would produce something with the depth, fire and bitter humour of his classic 1965-66 period. Yet in Dirge, Wedding Song and a handful of the other tracks on the album, he showed that he was still capable of plumbing those depths. Soon he would be back on the road for a major tour, he would be hitting the folk clubs in Greenwich Village again and he would be producing albums of songs that stood comparison to his finest work. But within a year or two, his marriage – and thus his settled domestic life – had fallen apart.Dirge thus stands as a kind of elegy for that life and a testament to one of the uncomfortable truths of Dylan’s life – that personal happiness and artistic fulfilment and were, for him, rarely compatible. But Dirge demonstrates a renewed determination to find that elusive ‘gem’ that somehow, over the years, he had lost.

DAILY DYLAN NEWS at the wonderful EXPECTING RAIN

THE BOB DYLAN PROJECT- COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS

STILL ON THE ROAD – ALL DYLAN’S GIGS

Leave a Reply