…This isn’t champagne anymore. We went through the champagne a long time ago. This is serious stuff. The days of champagne are long gone…

Sam Shepard, True West

Bob Dylan’s Brownsville Girl

is an extraordinarily experimental song which is a unique amalgam of lyrical, cinematic and theatrical elements. Its use of fractured internal and external narratives and time frames links it to earlier songs like Tangled Up in Blue and Visions of Johanna. But it uses language in a very different way. The lyrics were co-written with leading American playwright and actor Sam Shepard. Part sung and part spoken, it mixes startling poetic imagery with prosaic and clichéd expressions in what is often a highly disarming manner. The music follows a basic pattern of rhythmic repetition, allowing Dylan to enunciate a number of extended lines, as many blues singers are wont to do. These lines also do much to give the song the flavour of the heightened ‘everyday speech’ favoured by the most influential modern dramatists such as Harold Pinter and Arthur Miller. The song is held together by a distinctly ‘sing-along’ chorus which appears at unusually spaced out intervals. The first chorus appears after six verses, the second and third after four verses and the final one after another three verses. This distorts the ‘time continuum’ of the song, making it appear shorter than its twelve minute length.

SAM SHEPARD

The song combines elements of the fractured ‘cubist’ narratives that Dylan experimented with in songs like Tangled Up in Blue, Idiot Wind and Isis with Shepard’s preoccupations with alienated characters and the landscape of the American West. It focuses on the often unreliable recollection of memories and thoughts in the narrator’s mind which, in the manner of inner thoughts, do not always appear chronologically. Much of the song concerns reminiscences of a road trip through Texas and nearby states that the narrator went on with the woman who the song is addressed to. We are given various, often random, details of their relationship. As we follow the narrator’s thoughts, the narrative is framed by his recollections of an old Hollywood movie which – or so he claims – he only half remembers. His immersion in this drama casts doubt on the story he recounts, which we might consider to be another movie that he is replaying in his head. Yet whether the story is ‘real’ is irrelevant. What is important here is the emotional truth that the song conveys. At times the narrator reveals feelings of regret, passion and nostalgia that have a profound emotional impact.

Brownsville Girl – Dylan and Shepard

Dylan and Shepard had collaborated before. In 1975 Shepard wrote a script for Dylan’s film Renaldo and Clara and accompanied the musicians on much of the first leg of the Rolling Thunder tour. As he reveals in the Rolling Thunder Logbook, his idiosyncratic account of the tour, much of his text was not used in the movie as Dylan tended to favour more improvised scenes. But the disassociated sensibility of the film, which focuses particularly on issues of identity, has a number of links to Brownsville Girl, especially in its mixture of Shepard’s typically offhand, laconic dialogue and Dylanesque symbolism. Like Renaldo, Brownsville Girl is a kind of ‘road movie’ in which the characters can be said to be constantly travelling in order to ‘discover themselves’. In that sense both works have a debt to Kerouac’s On the Road. Shepard had a long and prolific career, producing over fifty plays and appearing in around seventy films. His plays often feature ‘outsider’ characters, include surreal and poetic moments and elements of black comedy, which he uses to make what are often barbed comments about American society. Perhaps his most famous work is True West (1982), an intermittently funny and tragic satire on the Hollywood screenwriting system and the quintessentially American values it represents. In 1987 Shepard wrote True Dylan, a one act play consisting of a dramatised ‘interview’ with Dylan. He was also involved as a screenwriter for Zabriskie Point (1970), Oh! Calcutta (1972) and Paris, Texas (1984) and went on to direct a number of films.

DYLAN AND SHEPARD ON ROLLING THUNDER TOUR

Brownsville Girl appears on what is generally considered to be one of Dylan’s weakest albums, 1986’s Knocked Out Loaded. The album, which was almost universally panned by critics, features rather forgettable songs co-written with Tom Petty and Carole Bayer Sager, a couple of inconsequential Dylan compositions and several rather lacklustre cover versions. Despite the fact that it was released while Dylan was on tour with Tom Petty and thehttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2Qz7GvGQH94 Heartbreakers, very few of the songs were ever featured in a live context. There was one live attempt at Brownsville Girl at Paso Robles on 6th August 1986 but the performance was half hearted to say the least, consisting almost entirely of repetition of the chorus. There is thus a sense in which the song has thus been ‘buried’ in Dylan’s oeuvre. In today’s parlance, it might be regarded as his ultimate ‘deep cut’. There are few cover versions, although Reggie Watts’ Dancehall arrangement (which omits most of the lyrics) is oddly effective. Bonnie Prince Billy’s gentle and subtly reflective live cover of the song (2012) is a highly moving rendition.

A previous version, New Danville Girl, was recorded in 1984 during the Empire Burlesque sessions. Two takes exist, one of which later appeared on the Bootleg Series release Springtime in New York. The other recording was partly utilised in the quite extensive studio overdubs that were added to Brownsville Girl. The lyrics were also considerably revised, presumably by Dylan alone. The chorus, which runs … New Danville girl, with your Danville curl/ Teeth like pears, shining like the moon above/ New Danville girl, take me all around the world/ New Danville Girl, you’re my honey love… is a series of pure clichés which works as an ironic contrast to the ‘literary’ nature of the verses. In the rewriting, ‘Brownsville’ (which is a town in Texas) was substituted for ‘New Danville’, presumably as it fits better with the setting of the song in the American South West. The chorus seems to have evolved from lines in Danville Girl, a traditional American folk song that was adapted and performed by Woody Guthrie and which refers to a ‘Danville girl with a Danville curl’, although otherwise the songs have little in common.

The epic nature of the revised song is enhanced by the presence of Dylan’s backing singers (Carolyn Dennis, Peggi Blu, Madelyn Quebec and Annette May Thomas) whose interjections enliven the recording and form a counterpoint to Dylan’s mostly spoken vocals. The opening verses begin with a sparse musical backing of bass and drums. As the song unfolds various other musical elements are added. Sax player Steve Douglas, a member of the 1978 touring band, is featured prominently as the song rises to its climax. Al Kooper also supplies some atmospheric washes of organ. The revised version of the song thus has a kind of symphonic sweep that is very unusual in Dylan’s work.

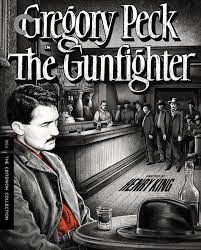

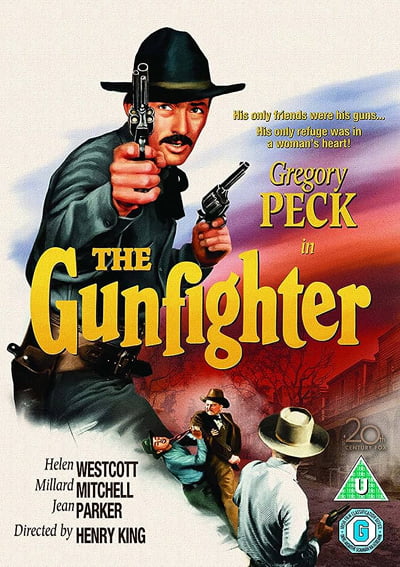

GREGORY PECK IN ‘THE GUNFIGHTER’

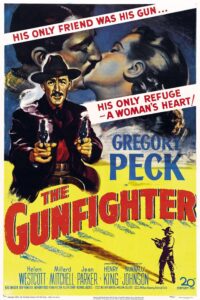

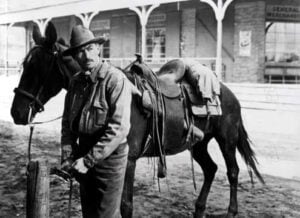

The first two verses consist of the narrator’s memories of the movie The Gunfighter, a 1950 Western directed by Henry King and featuring a memorably restrained and thoughtful performance by Gregory Peck in the role of a disillusioned middle aged gunslinger, Johnny Ringo, who is notoriously fast on the draw and has therefore acquired considerable fame across the West (as did famous outlaws like Jesse James and Billy The Kid). As a result of his notoriety he is often challenged by younger men who wish to achieve similar heights of celebrity by killing him. Eventually he is shot in the back by a cocky young buck. But as he is dying he lies that he ‘drew first’, meaning that the boy will not be hanged for the murder. This might appear to be an act of supreme personal generosity. But Ringo gets his revenge by knowing that the boy’s life will become like his. Having acquired the reputation as ‘the man who shot Johnny Ringo’ he will become a target himself, living constantly in fear that some new challenger will try to ‘take him out’ in order to achieve a similar level of fame.

RINGO AND ‘THE KID’

The film is one of a series of ‘revisionist Westerns’ made in the 1950s (an era in which the Western was the dominant Hollywood genre) which introduce variations on the conventions established in hundreds of previous cowboy movies., often in order to comment on contemporary issues. Perhaps the most well known is High Noon (1954), often seen as an allegory on the McCarthyite anti-communist witch hunts of the 1950s. Most ‘traditional’ Westerns end up in a shootout which is usually won by the hero. But in this case the boy merely shoots Ringo in the back. There are moments in the song when Dylan’s own voice appears to break through, where he reflects on his own position as an ageing rock star being challenged by ‘young guns’. Like Peck’s character, he seems disillusioned and exhausted by the pressures of fame. This is especially poignant given the generally negative reviews of his work in the late 1980s; an era in which he himself – as he later recalled in his memoir Chronicles Vol. 1 – thought of himself as being ‘washed up’ and claimed to have seriously considered retiring.

The story of the song is given another layer of meaning by the fact that Dylan himself was actually an avid fan of Gregory Peck, a brilliant film star who had a long and highly successful career. In 1997 Dylan appeared at the Kennedy Center in Washington DC to collect his award of the Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize, a prestigious award for those who had contributed greatly to the arts in America. At this event Peck, now 81 years old, revealed himself to be similarly enamoured with Dylan. In his speech he made a direct reference to the song:

GREGORY PECK MAKING THE SPEECH

…Dylan was singing about a picture that I made called The Gunfighter about the lone man in town with people comin’ in to kill him and everybody wants him out of town before the shooting starts. When I met Bob, years later, I told him that meant a lot to me and the best way I could sum him up is to say Bob Dylan has never been about to get out of town before the shootin’ starts. Thank you, Mr. Dylan, for rocking the country…and the ages….

The opening two verses recount the action at the climax of the movie. The narrator’s faux-naïve recollections begin with …There was this movie I seen one time/ About a man ridin’ across the desert and it starred Gregory Peck…. He then tells the story of the ending of The Gunfighter, summing up Johnny Ringo’s final words by putting himself in the place of the dying gunfighter and declaring that …I want him to feel what it’s like to every moment face his death… For the next four verses, we ‘cut’ to the narrator telling us how much his relationship with ‘The Girl’ still dominates his thoughts despite now being with a different woman. In the first of these verses he establishes both the narrative tone and the main subject of the song: …Well, I keep seeing this stuff and it just comes a-rolling in/ And you know it blows right through me like a ball and chain…. Already he reveals how difficult remembering the affair is for him and how he is ‘tied’ to it. He addresses The Girl directly, presumably from afar, establishing the regret that will dominate the song: …You know I can’t believe we’ve lived so long and are still so far apart/ The memory of you keeps callin’ after me like a rollin’ train… The conjunction of ‘ball and chain’ and ‘train’ is a rather awkward mixed metaphor. But this establishes the uncertain tone of the narrator’s voice, which is constantly trying to do justice to his memory of the relationship, yet often falls short.

THE PAINTED DESERT

In the next verse the mixture of ‘close ups’ and emotional reflection shows Dylan and Shepard working together with great effectiveness. The evocative image conjured up by …I can still see the day that you came to me on the Painted Desert/ In your busted down Ford and your platform heels… is highly cinematic in its attention to specific detail. The Painted Desert is an area of northern Texas and Oklahoma, while the description of the ‘busted down’ car is contrasted with the depiction of the woman as wearing the kind of impractical footwear that was especially popular in the 1970s. This immediately establishes her character as being both adventurous and self consciously showy. The following (equally economical) lines convey the narrator’s nostalgic longing with great emotional force: …I could never figure out why you chose that particular place to meet/ Ah, but you were right. It was perfect as I got in behind the wheel…

We then hear an account of their ‘freewheeling’ journey through Texas. They drive all night to San Antone and then sleep …near the Alamo… which is, of course, one of the most iconic sites in the USA. The narrator’s memory of their love making is very effectively and economically expressed in the simple line …Your skin was so tender and soft… a highly visceral description. Suddenly they are …way down in Mexico… where she goes out to find a doctor but never returns. This action, which has some similarity to the end of On the Road when Dean Moriarty deserts Sal Paradise with no explanation, suggests that she may have had some unknown motive for her disappearance. This, however, remains a mystery, as does the narrator’s assertion that …I would have gone after you but I didn’t feel like getting my head blown off… This is the first suggestion of his involvement with some kind of criminal activity.

The final verse of the first section is particularly revealing, beginning with another highly cinematic description as the narrator now takes us into what we seems to be the ‘present moment’ of the story: …Well, we’re drivin’ this car and the sun is coming up over the Rockies… We may at first assume that this is a continuation of the journey described in the last few verses. But the geographical reference tells us that in fact he is now on a different road trip, which is considerably further West. Just as the Western genre came to encapsulate and represent the mores of American culture, so the notion of ‘The West’ itself became symbolic of the uniqueness of that culture, in which the inhabitants were always pushing the national consciousness into ‘new frontiers’. Many of Shepard’s plays are set in the modern West and cast a dubious light on such notions.

Dylan then delivers several lines in which he breaks away from the rhythm of the song, expressing his feelings in a kind of stream of consciousness. Her reveals that he is now with a different woman. In the next line … Now I know she ain’t you but she’s here and she’s got that dark rhythm in her soul… it is suggested that he is with this woman because of her resemblance to the Brownsville Girl, thus suggesting that in his current life he is ‘living a lie’. Despite being with a different lover, he continues to address The Girl in his mind: …But I’m too over the edge and I ain’t in the mood anymore to remember the times when I was your only man… This long line is followed by the terse …And she don’t want to remind me. She knows this car would go out of control… suggesting that this other woman is quite aware of his obsession with his previous lover.

The second section begins with three verses in which the narrator continues his account of his earlier road trip. We now appear to have stepped back in time to before The Girl’s desertion. They head into Northern Texas to where …Henry Porter used to live… Mr. Porter, who is said to …own a wrecking lot outside of town… is not at home but Ruby (presumably his wife), who …had her red hair tied back… entertains them. The use of language here, with its very specific naming of people and places, often resembles Shepard’s theatrical dialogue. Ruby seems like a typical Shepard ‘outsider’ living on the margins of society. Ruby is very disillusioned with where she lives, telling them that …times were tough and how she was thinkin’ of bummin ‘ a ride back to from where she started… She confesses rather memorably that …Even the swap meets around here are getting pretty corrupt… She asks them where they are going and the narrator replies, with considerable gusto: …We’re going all the way till the wheels fall off and burn/ ‘Til the sun peels the paint and the seat covers fade and the water moccasin dies… Water moccasins are venomous snakes which live in Southern parts of the USA. Ruby’s reaction is to joke that …Ah! You know some babies never learn…. It is clear that they are on a Kerouac-type road trip here in which the journey is more important than the destination. The narrator is clearly idealising their relationship in a highly romantic manner. He seems to assume here that their road trip will be an endless one.

In the last verse of this section, the narrator’s mind switches back to the Gregory Peck movie. This pattern will continue in the succeeding sections. Now the song takes a rather surreal turn: …Something about that movie though, well I just can’t get it out of my head/ But I can’t remember why I was in it or what part I was supposed to play… Here the narrator appears to ‘break the fourth wall’, apparently fantasising that he himself was in the movie and that the other characters …seemed to be looking my way… Perhaps this revelation may lead us to question the veracity of all the narrator’s memories in the song. Were they real or was he imaging some kind of road movie in his head?

LITTLE RICHARD WITH ‘POMPADOUR’

In the third section there are more hints that the narrator is on the run from the police. Again we are provided with selected fragments of his memory so it is impossible to tell what has really happened. We are first told, rather bizarrely, that …They were looking for someone with a pompadour… a hairstyle that was popular in the 1950s and was worn by Elvis Presley, Tony Curtis and – most spectacularly – the flamboyant Little Richard, Dylan’s early hero. The narrator recalls being shot at and delivers the wonderfully funny deadpan line …I didn’t know whether to duck or run… so I ran… We then learn that The Girl made a court appearance, saving him by testifying that he was with her at the time of the crime. We never find out, however, what this crime actually was.

As the song nears its climax, more and more lines seem to suggest that the voice of Dylan himself is now coming through, in his typically enigmatic way. We learn that The Girl had seen his photo in the local paper with the caption …A man with no alibi… which recalls previous ‘offhand’ Dylan characterisations such as Alias in Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973). The long line ….Now I’ve always been the kind of person that doesn’t like to trespass, but sometimes you just find yourself over the line… sounds like a confession of regret from someone who has the habit of pushing his relationships – or other involvements – too far. In another highly ambiguous and funny statement he declares …If there’s an original thought out there I could use it right now… At the time many listeners took this to refer to the lack of inspiration that Dylan appeared to be suffering from in the late 1980s. The line is ironic, though, as the last thing that Brownsville Girl is short of is a lack of originality. Having delivered this ‘confession’, we are presented with a memory of him ‘standing in line’ to see a Gregory Peck movie, which may or may not be the film previously referred to. Dylan tells us that …he’ll see him in anything… Thus the narrator and Dylan himself appear to be merging personalities, while the memories being related become more and more suspect. It may be argued that the unreliability of memory is one of the main themes of the song.

By the time we reach the final three verse section, the memories of the relationship with The Girl are dissolving. All we are left with is a series of enigmas. In a conversational tone, the narrator begins to philosophise about fate: …You know, it’s funny how things never turn out the way you had ‘em planned… which is a kind of inverted version of the famous line from It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue: …Take what you have gathered from coincidence… It seems that Dylan is looking back to his younger days, with the sad reflection that the spontaneity that fuelled his earlier work has now dissolved, along with many of his actual memories. Years later, in Chronicles Vol. 1, Dylan would write an entire ‘autobiography’ in which the veracity of memory was constantly being challenged.

The final details of the story merely create yet more enigmas. In another memorably funny line we hear that …The only thing we knew for sure about Henry Porter is that his name wasn’t Henry Porter… That is also the only thing that we as listeners learn about this character. We are told that …there was somethin’ about you baby that I liked that was always too good for this world… but we are never told what that ‘somethin’ is. This line is mirrored by the statement that … Just like you always said there was somethin’ about me you liked that I left behind in the French Quarter… (presumably a reference to a district of the Texas state capitol Austin). Again, the nature of that mysterious ‘somethin’ is left to our imagination.

The narrator then reflects that … Strange how people who suffer together have stronger connections than people who are most content… a line which recalls She’s Your Lover Now’s …pain sure brings out the best in people, doesn’t it… Dylan has always been attracted to such ironic reflections. When he sings …I don’t have any regrets, they can talk about me plenty when I’m gone… it is hard to believe that this is not the voice of the singer himself. The bleak philosophical stance of …You always said people don’t do what they believe in, they just do what’s most convenient and then they repent… (which is quite a mouthful, even for Dylan)… is countered by a return to the ‘anything goes’ attitude of …And I always said “Hang onto me baby, and let’s hope the roof stays on!”…. In a rather triumphant way, Dylan takes us back to ‘taking what we have gathered from co-incidence’. Despite all the emotional uncertainties and upheavals in the song, it seems that the narrator – like Edith Piaf in her iconic song Je Ne Regrette Rien – truly has no regrets. Despite his doubts and uncertainties, he still celebrates the freedom that the open road represents.

The ‘Brownsville Girl’ herself remains a truly inscrutable figure. We are never told what she looks like, where she comes from or what her motivations are. Like the girl on the Red River Shore or the subject of Just Like a Woman, she appears to be more like a collection of memories than a real person. Perhaps she is merely as aspect of Dylan’s own imagination. Dylan appears to be using his narrator to look back from middle age on the wild excesses of youth and his own dedication to being always ‘on the (metaphorical) road’ in terms of his constant changes of style and ‘freewheeling’ attitude to art and life. The song is a kind of meditation of the persistence of memory itself. Despite all the disappointments and wrong turnings in life it recounts, it ends rather triumphantly, with the lovers being back on the highway, not knowing where that road will leave them.

Finally we return to the narrator’s memories of The Gunfighter. He admits, however, that he does not recall much of the movie’s plot. The movie itself now functions as a kind of cipher for his own disintegrating memories …It seems like a long time ago… he reflects, in the highly ambiguous final line …Long before the stars were torn down… These stars may be actual stars or Hollywood stars like Gregory Peck. We are literally left in the darkness, rather like the traditional end of a movie which goes to a black screen and tells us that we have reached ‘The End’.

Brownsville Girl takes us on a very unusual rollercoaster ride. In doing so it uses the enigmatic language that is characteristic of the modern hyper-realistic dramas of playwrights like Shepard, mixed with cinematic flashbacks and flash forwards to tell a story whose ‘reality’ is psychological rather than historical. All this is held together by apparently highly sentimental and romantic choruses, which provide a kind of blessed relief from the contorted narrative. As in a number of other Dylan songs, the framework of a love song is presented ironically, with Dylan using this conventional structure to reflect on psychological realities. The song is crammed with ironic humour and nostalgia. But it is also infused with a particular determination to carry on exploring the elements of the creative imagination. It is a song, like so many others in Dylan’s catalogue, about the struggle to retain or regain artistic inspiration in the face of a world with little understanding of the real rigours of the process of artistic creation.

Leave a Reply