BOB DYLAN: BALLAD OF A THIN MAN: SOMETHING IS HAPPENING HERE…

… You don’t necessarily have to write to be a poet. Some people work in gas stations and they’re poets. I don’t call myself a poet, because I don’t like the word. I’m a trapeze artist…

Bob Dylan, interview with Nora Ephron and Susan Edmiston (late summer 1965)

… Back in the fifties in the Midwest they used to have these carnivals come through town. There used to always be this character called the geek… … a geek is a man who’s working as a job of eating a live chicken. Bites his head off first and then he eats the rest of him. Head and all. Anyway it cost a quarter to see this dude. I can tell you if you think you’re funky, this dude is low-down all the way. Anyway I didn’t want to get too tight with him but regardless of that he did tell me one thing which helped me in years later. He used to always think of other people as being freaks. And that’s helped me a lot as I go through life...

Bob Dylan on stage at Inglewood Forum (Los Angeles 15/11/1978)

“There must have been moments even that afternoon when Daisy tumbled short of his dreams—not through her own fault, but because of the colossal vitality of his illusion. It had gone beyond her, beyond everything. He had thrown himself into it with a creative passion, adding to it all the time, decking it out with every bright feather that drifted his way. No amount of fire or freshness can challenge what a man can store up in his ghostly heart.”

F, Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby (1925)

BOB DYLAN AND BALLAD OF A THIN MAN

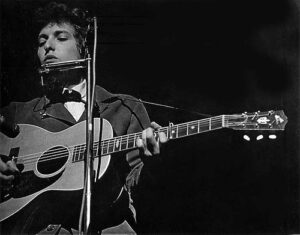

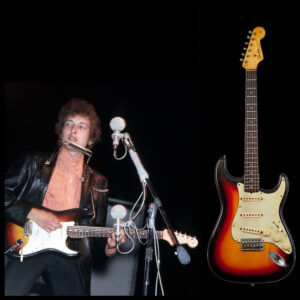

By the mid ‘60s, when his creativity was at its absolute inspirational zenith, Bob Dylan was in a unique position. He was already one of the world’s most famous ‘pop stars’. Countless other respected musicians had paid tribute to him. His distinctive appearance made him immediately recognisable, as did his always controversial musical and vocal styles. Having initially become famous as a writer of ‘protest songs’ that quickly became political and generational anthems, he had been feted as a ‘leader’ of the so-called ‘youth revolution’. Yet he was also a serious poet (not to mention a musical polymath) whose idiosyncratic writing style led many of his fans to regard him as some kind of oracle of wisdom and truth. For a young man who had just turned 24, such burdens might have proved impossible to handle.

Dylan, however, had some especially unusual coping mechanisms. In interviews, in order to dodge ‘dumb ass’ questions from journalists who frequently tried to categorise him in some way, or ‘dig some dirt’ on his private life, he often responded with hilariously ironic ‘put ons’; describing himself as a ‘song and dance man’ or a ‘trapeze artist’. In the film Don’t Look Back, which catalogued his last acoustic tour of Britain in 1965, he can be seen delivering scathing responses to press men who ask him particularly insensitive questions. After his move into rock music later in the same year the pressures became even more intense. Several of the songs he released at that time appeared to be (at least on the surface) bitingly scornful diatribes against those who misunderstood him. In Like a Rolling Stone, Positively Fourth Street and Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window he displayed his ‘acid tongue’ in full effect.

WHO IS MR. JONES IN BALLAD OF A THIN MAN?

Ballad of a Thin Man, in which his use of language and biting wit is especially barbed, was perhaps the apogee of this tendency. The character of ‘Mr. Jones’, who the song’s bile is directed at, is surely Dylan’s most famous creation, having been widely referred to in many contexts and even in the songs of others (most famously in John Lennon’s Yer Blues from The Beatles ‘White Album’). Over the years many Dylan fans and theorists have speculated as to the ‘real’ identity of this character. Some have pointed at Terry Ellis, the naïve young reporter in Don’t Look Back who later became a record company boss. Various real life figures, including the Rolling Stones’ Brian Jones (who was actually a friend of Dylan) have attempted to claim the dubious honour themselves.

The song is not really a ‘ballad’. In fact it rests on a conventional blues/rock structure which was changed little in the thousands of performances or in the many cover versions by the Grateful Dead, Elliot Smith and others. Dylan leads the music with his distinctive ‘stabbing’ piano style, which he utilises for an especially dramatic four note blues riff in the intro before the verses kick in. In some ways the music mimics that used in film scores, in a song whose bizarre events often resemble those in ‘art movies’ such as Fellini’s surreal 8½. Thin Man itself has strong cinematic qualities, as each listener is allowed to construct their own ‘imagined movie’ from the outlines Dylan presents.

The use of the direct second person address is a particularly strong feature of the song. The narrator speaks to the protagonist directly throughout the seven verses, the bridge and the highly distinctive chorus. In the first verse the ‘you’ address is used in every line: …You walk into the room…Dylan begins …with your pencil in your hand/ You see somebody naked and you say “Who is that man?”/ You try so hard but you don’t understand/ Just what you’re gonna say when you get home… We do not yet know where this person is. The references to the ‘pencil’ and the ‘naked man’ conjure up a mysterious picture. Then the first chorus tells us, in quite unequivocal terms, that …Something is happening here and you don’t know what it is… The dramatic question in the second line is highly pointed (like the pencil)… Do you, Mr. Jones?… Already the song has a disturbingly hallucinogenic quality.

The next verse consists of a bizarre conversation with two shadowy figures. But it still gives us no context whatsoever. All we can assume is that the protagonist is somehow ‘lost’: …You raise up your head and you ask “Is this where it is?”/ And somebody points to you and says “It’s his”… Like Jones, we remain in physical and spiritual darkness. Even the unnamed character in this verse is pointing at him. The next lines still provide no explanation: …And you say “Well, what’s mine?” and somebody else says …“Well, what is?”/ And you say “Oh my God, am I here all alone?”….But the appeal to a higher power is futile, as the chorus repeats the same message.

We are then given a somewhat clearer impression of where Jones actually is: …You hand in your ticket and go watch the geek/ Who immediately walks up to you when he hears you speak… Now we know that he is obviously in some kind of carnival. In the early twentieth century the term ‘geek’ was used for a rather pitiful circus performer, who acted as a ‘warm up’ act for a freak show, but whose only role was to bite the heads off live chickens. The term is nowadays used to refer to a person who is obsessively interested in something, often especially related to computers or technical subjects. Mr. Jones has been bombarded with questions already, but the one the geek asks him is particularly striking, given that it is the question that we might expect Jones to ask him …How does it feel… the geek asks icily …to be such a freak?… Jones’ response is to mumble …”Impossible…” as the geek …hands him a bone… (presumably from a still quivering chicken). It is well known that, due to continuing muscle spasms, chickens may still continue to run around after they are beheaded. Thus Jones himself is reduced to the status of a ‘headless chicken’.

Carnivals and circuses have always fascinated Dylan. The first line of Desolation Row announces that …the circus is in town… and in one sense all the characters in that song may be seen as circus performers. Years before, in his earliest interviews, Dylan had constructed many fabrications about his life, claiming to have run away from home at a very tender age and to have spent much of his youth travelling around the country working in carnivals and circuses. This completely fictional back story had been heavily romanticized in his unreleased ‘autobiographical’ 1963 composition Dusty Old Fairgrounds.

The bridge section gives us some insight into who Mr. Jones really is, although the description we are given is hardly complimentary: …You have many contacts among the lumberjacks… Dylan sneers, delighting in the ironic internal rhyming that will continue in …to get you facts when someone attacks your imagination… These rhymes coincide with the jabbing piano chords, as we move into a new area entirely, punctuated again by three internal rhymes: …And nobody has any respect/ Anyway, they already expect/ You to give a check to tax deductible charity organizations… The tone of the song has now changed, as we learn that Mr. Jones is some kind of well-heeled professional person. It is unlikely, however, that he associates with real ‘lumberjacks’.

Jones’ refinement or education will still not help him to comprehend what is going on, as we learn in the next lines: ...You’ve been with the professors and they’ve all liked your looks… Then the narrator really ‘sticks the knife in’: …With great scholars you’ve discussed lepers and crooks/ You’ve been through all of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s books/ You’re very well read, It’s well known… Dylan draws out the pronunciation of the last line, which emphasises with great sarcasm that an intellectual understanding – even of the works of one of the USA’s most esteemed authors – will not help our hapless protagonist cope with the barrage of unfamiliar images and information that he is being confronted with. The verse is positively dripping with venom but the shape and possible meaning of the song is becoming clearer. In this unfamiliar environment, the protagonist – despite being an intellectual – still does not comprehend the meaning of the geek telling him that it is he, Mr. Jones, who is actually the ‘freak’. This is, of course, a reversal of what might be expected but Jones, like the eponymous hero of Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, still cannot see through his own illusions. Jones may have ‘been through’ Fitzgerald’s books but he does not grasp their essence. Here Dylan lets loose on academics, few of whom at this point accepted his work (or that of his mentor Allen Ginsberg) as serious poetry. Jones has also ‘discussed lepers and crooks’ with supposed ‘great scholars’ but clearly has no actual understanding of what being such an outsider from society actually involves.

Jones is then confronted by two other circus performers – a ‘sword swallower’ and a ‘one eyed midget’. The sword swallower ‘performs’ a similar trick to the geek, in which his role and that of Jones are reversed. First of all, he…comes up to you and then he kneels/ He crosses himself then he clicks his high heels… This is the particular line which has often been taken to indicate that, in reality, Jones has actually stumbled into a gay bar or bath house and that the ‘sword swallower’ (who is dressed in ‘high heels’) is kneeling to perform fellatio on him. This is reinforced by the following lines …And without further notice he asks you how it feels/ He says “Here is your throat back, thanks for the loan”… although all of these lines could be equally applied, in a curious way, to an actual sword swallower who has ‘borrowed’ Jones’ throat for his performance.

The penultimate verse is perhaps the song’s most darkly humorous. The midget shouts the word “Now!” at Jones. He asks…”For what reason?”… The midget’s response is to merely respond, like a stereotyped Hollywood Indian, with the word …How?… Jones’ demand for an explanation is met with a hysterical cry of …”You’re a cow! Give me some milk or go home… (another line which, although apparently completely nonsensical, has had ‘gay’ connotations attached to it, ‘milk’ being taken to stand for ‘semen’). Then we get a very surreal description of Jones’ state of confusion, whose first words return us to the opening line of the song, as if we are in some kind of temporal loop: …You walk into the room like a camel and you frown/ You put your eyes in your pocket and your nose in the ground… Finally the narrator, showing no mercy on Jones, turns his ire directly on him: …They’re ought to be a law against you coming around… he sneers …You should be made to wear ear phones…

The final verses seem to take us into a ‘nonsense world’, mirroring Jones’ utter incomprehension of what he has experienced. The narrator condemns him, sarcastically telling him that his ears might as well be shielded from all this mayhem as he still does not comprehend what is going on. It is left to the listener to imagine what the ‘real story’ of the song is. Is the protagonist a repressed gay man who cannot really acknowledge his own sexuality? Is he an academic who lives so much ‘in his brain’ that he cannot come to grips with ‘real life’? Is he indeed that young reporter with no understanding of the ambiguity of symbolist poetry? Is he even the ‘well read’ Dylan himself, depicted in some kind of mad dream to which there is no rational explanation? Or is ‘Mr. Jones’ – the man with such a commonplace name – an ‘everyman’ figure caught up in an illogical, irrational world? Is he you – the listener – or me – the commentator, trying to make sense of a world in which we feel we are outsiders or even outcasts?

Of course, Mr. Jones is all of these things, or perhaps none of them. But this is certainly a song which all of those who lived outside the norms of conventional society can identify. In one sense it is a metaphor for the lack of comprehension of what later became known as the ‘counter culture’ which was so often demonstrated by the denizens of conventional decency and taste. On another level, it is a broadly satirical response to all of those fans, reporters and commentators who had wanted him to explain what his songs ‘meant’.

Its wide appeal lies in the way that Dylan transforms personal concerns into universal statements, not only about the role of art in society but also about how particular messages, symbols or actions can be interpreted (or perhaps more importantly, misinterpreted) in a multiplicity of ways. If any one work can be said to epitomise and celebrate the ambiguity and potential multiple meanings in Dylan’s songs, this is it.

Or perhaps, following the surrealist ideal, such poetry as this is not meant to be ‘understood’ in any kind of rational sense. Perhaps Dylan is merely taunting us, throwing images at us, challenging us to make sense of them. Something is happening here, it seems, but we cannot with any certainty really say what it is…

Leave a Reply