…This I say then, walk in the Spirit, and ye shall not fulfil the lust of the flesh. For the flesh lusteth against the Spirit, and the Spirit against the flesh: and these are contrary the one to the other: so that ye cannot do the things that ye would….

Galatians 5: 16-17

John Wesley Harding

In the wake of his motorbike crash and his withdrawal from public appearances in the mid 1960s, Bob Dylan began composing songs with more compressed poetic imagery. When John Wesley Harding first appeared at the end of 1967, it was clear that he had taken a step back from the expansive and often delirious poetic ‘rush’ of the material on Blonde on Blonde. The album was recorded in Nashville with a small backing band, mainly comprising Charlie McCoy on bass and Kenny Buttrey on drums. The understated songs were shorter, his vocals now more subdued and his musical presentation was minimal. On closer examination, however, it can be argued that the cryptic vignettes he is now presenting are just as beguiling and ambiguous as those of his celebrated 1965-66 period. The emphasis in the songs is clearly on the verbal games Dylan plays with us, which are foregrounded at the expense of musical ‘colour’. The songs are like Chinese puzzles. Once we ‘open them up’ they become even more mysterious.

CHARLIE McCOY KENNY BUTTREY

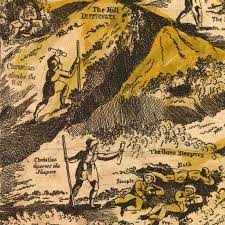

Dylan appears to be struggling with the after effects of his previously excessive lifestyle. Several songs display a distinct yearning for spiritual fulfilment, although it is arguable that Dylan himself does not at this point have any clear spiritual direction. It has been reported that, in the wake of his retreat, he became very interested in studying the Bible and other religious works. On the album he often refers to or quotes from Biblical passages. In places his tone imitates the grand style and lexicon of the King James Bible. John Bunyan’s classic religious allegory The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678) and other religious works, particularly St. Augustine of Hippo’s Confessions (early 6th century) are other influences. The songs can be seen as parables in which he wrestles with moral and existential issues

PILGRIM’S PROGRESS

John Wesley Harding…

Dear Landlord is a beautifully expressive ballad featuring a very committed and soulful vocal from Dylan, who leads the recording on piano. The narrator sings with the voice of bitter experience, apparently leaving much ‘unsaid’. We can only wonder what has brought him to this point but it is certainly true that the tone of the song can be described as ‘sober’. Dylan’s narrator begins with a striking – and perhaps somewhat fearful – plea: …Dear landlord, please don’t put a price on my soul… Then he tells us that …My burden is heavy/ My dreams are beyond control… There is a definite suggestion of spiritual dissatisfaction here, as if the narrator is caught in a tussle with his own conscience. He appears to be pleading for salvation but admits that, because of his ‘uncontrollable dreams’, this will be particularly difficult to achieve. The reference to a ‘burden’ seems to mirror the fate of Christian, the protagonist of Pilgrim’s Progress, who tries throughout the book to rid himself of the burden of sin. In Confessions (Book 10, Chapter 30) St. Augustine, who confesses to having led a rather hedonistic and sinful life when he was younger, writes about the difficulties of leading a moral life when his dreams lead him back towards his old ways. Having stepped off the ‘rock and roll treadmill’, with all its temptations and distractions, Dylan is trying to live such a life. But he fears that, having given into such enticements before, he will inevitably fall back into his old behaviour.

The rather weird diction of: …When that steamboat whistle blows/ I’m going to give you all I have to give/ And I do hope you receive it well/ Depending on the way you feel that you live… necessitates some complex piano figures as Dylan squeezes the words in. This adds a further level of uncertainty to the narrator’s anxious protestations. Jacob Abbot, in his 1832 work Young Christian, describes the building and operation of a steamboat as a metaphor for life and death. In country pioneer Roy Acuff’s song Steamboat Whistle Blues (1935) the narrator laments not being able to hear the familiar Mississippi steamboat whistles as he is incarcerated in jail. This steamboat could be interpreted as the ‘whistle’ that blows at the end of life or the ‘whistle’ that sets the ‘ship of life’ in motion. The humble admonition of the last two tongue twisting lines appears to be begging the ‘landlord’ for approval.

ROY ACUFF

John Wesley Harding…

But who actually is this ‘landlord’? Many commentators assume that the narrator is addressing God, who according to believers is a kind of ‘landlord’ for us in our earthly existence. The reference to ‘selling souls’, however, tends to suggest that he is preparing to enter into a Faustian pact with the Devil. Lines in the next verse tend to rule out either of those options. Although they begin with another humble plea: …Dear landlord, please heed these words I speak… this is followed by …I know you’ve suffered much, but in this you are not so unique… It is hard to conceive of either God or the Devil having ‘suffered much’. Already we are beginning to get the impression that the narrator is actually addressing himself. This is reinforced by what follows: …All of us at times we might work too hard/ To have it too fast or too much… This may a description of the ‘burn out’ that Dylan experienced after the gruelling 1966 ‘going electric’ tour. He then shifts to a philosophical reflection: …Anyone can fill his life up with things/ He can see but he just cannot touch… This echoes the famous lines from Matthew 16: 26:

…For what is a man profited, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul? or what shall a man give in exchange for his soul?…

These lines also conjure up the pitiful fate of Charles Foster Kane in Orson Welles’ cinematic masterpiece Citizen Kane. Despite all the wealth and power he has achieved, Kane ends up living alone in his huge mansion Xanadu, which is crammed with expensive material objects. Dylan’s reflection here on the well worn idea that material things do not bring spiritual fulfilment has great poignancy. But like Augustine, he seems to feel that it is very hard for him to resist such earthly delights. And like Kane, he is imprisoned by the trappings of the material world.

CITIZEN KANE

In the third and final verse, the narrator presents the landlord as a kind of cosmic judge …Please don’t dismiss my case… he pleads. …I’m not about to argue/ I’m not about to move to no other place… He is determined to stand firm on his principles but he remains desperate for the ‘landlord’ to accept him. Then, as in the previous verse, he universalises his situation: …Now each of us has his own special gift/ And you know this was meant to be true… This echoes Corinthians 7:7: …But each of us has his own special gift from God, one of one kind and one of another… There is a clear sense that, despite the humility of his address, he seems to regard the landlord as an equal. It may be that the narrative of the song consists on an allegorical conversation between the body and the soul. As with many early Christian homilies, it is the voice of the soul that we hear, begging the creator not to ‘put a price’ on him and showing an awareness of the toll that excessive hedonistic living may place on the body. The soul accepts that his body has ‘suffered much’ through such self-abuse but makes the excuse that many others are in the same position.

It certainly seems that the narrator is engaged in a conflict between body and soul and between materialism and spirituality. But although Dylan places the lyrics in the literary context of the Bible and related works, he does not offer any solutions to the ongoing paradox that he presents so eloquently. The remarkably equivocal final lines, with their direct address: …If you don’t underestimate me/ I won’t underestimate you… indicate a striving to achieve a balance between body and soul and thus between materialism and spirituality. This struggle is not only ongoing but will continue to be so forever.

Dear Landlord has never been a regular feature of Dylan’s set lists, being played live only six times between 1992 and 2003. Most of the performances do not feature piano. At Sarasota on 9th November 1993 it is extended to seven minutes, with an extended instrumental passage and some relatively aggressive vocals. In Visala on 14th March 2000 it is slower and more reflective and thus closer to the original. The final live performance at Hammersmith Apollo on 24th November 2003 is marked by very distinctive guitar stylings by Freddie Koella. Most cover versions, like that of Fairport Convention (featuring Sandy Denny on vocals) and Joan Baez, are smooth and melodic, although covers by Joe Cocker and Janis Joplin adopt a more forceful and soulful approach.

The deeply reflective I Dreamed I Saw St. Augustine presents a considerable contrast. Whereas Dear Landlord expresses defiance and a determination to continue to struggle, here the narrator experiences a terrifying vision of spiritual desolation which cannot be overturned. Yet the raw terror of the song is restrained by its warm and expansive melody, which is derived from the early twentieth century protest ballad Joe Hill, a song about a victimised union leader who is executed by the US authorities for stirring up workers in revolt. Joan Baez performed this song at the Woodstock Festival in 1969. It is perhaps ironic that Dylan chose to frame this mysterious song around a protest ballad about a martyred figure when he himself had written songs about Hattie Carroll, Emmett Till, John Brown and Hollis Brown; all in their way ‘martyrs’, whether real or fictional. The first line of Dylan’s song: …I dreamed I saw St. Augustine, alive as you or me… is almost identical to the first line of Joe Hill: …I dreamed I saw Joe Hill last night, alive as you or me…

JOE HILL

In the narrator’s dream he pictures Augustine in a state of spiritual confusion which has spilled over into outright panic. The saint is glimpsed …tearing through these quarters in the utmost misery… The archaic-sounding ‘tearing through’ suggests that Augustine is not only going too quickly but is destroying everything in his path, while the use of the equally old fashioned ‘quarters’ to indicate a living space places the whole scene in some mythical scenario in the distant past. Again Dylan is mining the King James Bible. Exodus 13:7, when outlining the rules about what is kosher, states that:

…Unleavened bread shall be eaten seven days; and there shall no leavened bread be seen with thee, neither shall there be leaven seen with thee in all thy quarters…

In the narrator’s vision St. Augustine is said to have …a blanket underneath his arm and a coat of solid gold… and to be …searching for the very souls whom already have been sold… He appears to be engaged in an utterly futile task in his battle with the Devil, who has already claimed the souls he was trying to save. The strange (and perhaps impossible) image of ‘a coat of solid gold’ seems to suggest that he is, like the coat, impermeable to outside influences. The ‘blanket underneath his arm’ may imply that he is planning to engage on a journey in search of those ‘lost souls’. Dylan is not depicting Augustine as a figure whose faith sustains him but one who is caught up in utter confusion. The narrator’s dream may well be a mirror of the state of his own soul, focusing on Augustine’s failed attempts to bring salvation.

DYLAN’S DRAWING FOR ‘I DREAMED I SAW ST. AUGUSTINE’

Augustine, having failed to locate any souls to save, continues his increasingly desperate search with a vain appeal …“Arise, arise! “he cried so loud/ In a voice without restraint… He then appeals to all the ‘gifted kings and queens’ to hear his ‘sad complaint’. His complaint is that: …No martyr is among ye now/ Whom you can call your own/ So go on your way accordingly/ And know you’re not alone… ‘Arise!’, ‘ye’ and ‘accordingly’ are all commonly used in the King James Bible. Augustine’s search for a martyr, however, will be in vain. By this point in his career, many fans saw Dylan as a ‘prophetic’ figure who could provide them with ‘spiritual guidance’. The song can be taken to indicate Dylan’s own refusal to ‘martyr’ himself. But the narrator has internalised his feelings of guilt and is trying to discover a way of escaping from them. Augustine’s ineffective quest may represent his own inner failure to come to terms with the conflict between material and spiritual worlds.

In the final verse he now dreams that he sees Augustine …alive with fiery breath… Job 31-34 gives a graphic description of the monster Leviathan, a huge fire breathing dragon. In the dream, the saintly Augustine has been transformed into a supernatural being. We are also told that ...I dreamed I was among the ones who put him out to death… Again, Dylan’s use of language sounds oddly archaic. The confession of responsibility for Augustine’s martyrdom is somewhat ironic because Augustine had himself been searching for suitable martyrs. In real life, the saint died of natural causes. But here the figures of Augustine and Joe Hill are merged in the narrator’s fevered imagination. The dream vision ends abruptly, leaving the narrator bereft. Dylan delivers one of his most memorable closing couplets: …I awoke in anger, so alone and terrified/ I put my fingers against the glass and bowed my head and cried… His attempt to put his sinful life behind him has failed.

At the Isle of Wight Festival in 1969 the song is performed for the only time with The Band, who provide a rich musical setting with stirring backing vocals by Richard Manuel and Rick Danko. This gives a beguiling glimpse of what John Wesley Harding would have sounded like if The Band had backed Dylan up in the studio. The song is later given a more upbeat arrangement for the Rolling Thunder Tour, in which it is performed with Joan Baez. It is later revived with Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers in 1986, when it reverts to a slower pace. As with Dear Landlord, in live performance it is extended to allow for instrumental flourishes. Performances on the Never Ending Tour are rare. At Cork on 16th June 2011 it is given an impressively restrained and impeccably delivered outing. A 2016 recording by Eric Clapton treats the song with a surprisingly light touch, whereas Joan Baez is in her element, giving her all to this touching and emotive ballad.

I Pity the Poor Immigrant

I Pity the Poor Immigrant is another enigmatic lament which also deals with thorny moral issues. It has a distinctive, flowing melody (derived here from the traditional Scottish ballad Tramps and Hawkers) and is delivered calmly and reflectively. As with Augustine there is a considerable contrast between the darker elements of the text and the lugubrious way they are sung. But the moral panic of the previous song is replaced here by profound compassion. It begins fairly straightforwardly: …I pity the poor immigrant/ Who wishes he would have stayed home/ Who uses all his power to do evil/ But in the end is always left so alone…. portraying a person who has been thoroughly corrupted. As Dylan puts it so graphically …That man whom with his fingers cheats/ And who lies with every breath/ Who passionately hates his life/ And likewise fears his death… Some commentators have interpreted the ‘immigrant’ as a personification of white Americans (who are, of course, a ‘nation of immigrants’) with particular reference to the genocide that they inflicted on Native Americans. Others have seen the ‘immigrant’ as a Don Corleone type figure, a basically sympathetic character who turns to evil as a means of survival in the harsh rat race of American life. But there is little actual evidence in the text to support such assumptions. The final line recalls It’s Alright Ma, I’m Only Bleeding (1965) where Dylan lambasts ...those who think death’s honesty won’t fall upon them naturally… for whom …life sometimes must get lonely… The ‘immigrant’ is one such person. His life is a spiritual void. He is a liar and a cheat who has devoted himself to evil and who apparently lives in fear of divine judgement.

In the second verse, Dylan makes the moral dimension of the song explicit by referring to the book of Leviticus, a section of the Old Testament in which laws for human conduct are dispensed. We are told that the immigrant’s …strength is spent in vain… This phrase appears in Leviticus 26:20: …. And your strength shall be spent in vain: for your land shall not yield her increase, neither shall the trees of the land yield their fruits…. We are also told that his …heaven is like ironsides/ Whose tears are like rain… Leviticus 26:19 reads: … I will make your heaven as iron, and your earth as brass… The song continues: …Who eats but is not satisfied/ Who hears but does not see… Leviticus 26: 6 gives us …Ye shall eat, and not be satisfied… The final line of the verse: …He falls in love with wealth itself, and turns his back on me… with its neat internal rhyme, maintains the moralistic Biblical flavour.

Dylan’s Jewish heritage is clearly an influence on these songs. His deliberate use of Biblical terms and phrases throughout John Wesley Harding has a similar effect to his use of quotations from and musical references to old folk and blues material that characterise much of his work. The use of such language grounds his texts in a particular tradition and adds resonance to them. It should not be assumed, however, that Dylan actually subscribes to the Old Testament morality of a book from the Bible which is extremely misogynistic and homophobic. He is attracted by the richly metaphorical prose of the King James version, which give the songs a flavour of ancient wisdom. If the term ‘immigrant’ refers to any particular socio-historical group it may refer to the Jews, who historically have nearly always been ‘immigrants’ in others’ lands. Perhaps the ‘immigrant’ is a Jewish person who, having been subjected to prejudice and persecution, has reacted by internalising all this to become a purveyor of evil himself, no longer capable of compassion towards others, with a ‘heart of iron’. The use of a specifically Jewish text adds to this effect.

Despite his enumeration of the corruption of the immigrant, Dylan’s performance of the song is highly compassionate. His sonorous delivery and his repeated use of the word ‘pity’ demonstrate that he sympathises with the subject of the song. It seems that he also identifies himself closely with the figure he portrays here who, like the protagonist of St. Augustine, is struggling but failing to overcome his sinful nature. There is no easy way out of his dilemma. In the final verse we see the immigrant stuck in the moral quagmire he has created for himself …trampling through the mud… We hear that he becomes an exploitative conqueror, who takes delight in dispensing pain to others. He … fills his mouth with laughing/ But builds his town with blood… Perhaps the immigrant is one of the ‘chosen people’, who according to the Old Testament is given free rein to ‘ethnically cleanse’ the inhabitants of the ‘promised land’.

The ending of the song has some similarities to that of St. Augustine. While Augustine …puts his fingers against the glass… before breaking down, we are told that the immigrant’s …visions in the final end/ Must shatter like the glass… Proper ‘vision’ is impossible as the ‘glass’ that the protagonists are looking through has been broken. Dylan adds ...I pity the poor immigrant/ When his gladness comes to pass… Both ‘gladness’ and ‘comes to pass’ are frequently used in the King James Bible. ‘Gladness’ is a sixteenth century term for joy which, in the Biblical context, also indicates achieving approval from, and ultimately union with God. So the final lines are heavily ironic. The immigrant will never really achieve the ‘gladness’ of salvation. But the narrator does not condemn him. In contrast to the harsh Old Testament morality of books like Leviticus, he merely pities him.

This is another song which Dylan has performed relatively rarely. As with Augustine, it is given a soulful treatment at the Isle of Wight Festival, before becoming a regular feature of the second leg of the Rolling Thunder Tour in 1976. This version, again with shared vocals by Baez, is surprising light and almost comical in flavour, as if Dylan is mocking the song’s spiritual pretensions. After that it is performed only once, in the rehearsals for the MTV Unplugged live album. It has been recorded by Joan Baez, Judy Collins, Planxty and many others, usually in a similar arrangement to the original version.

On John Wesley Harding Dylan reflects on his own situation as he takes a step back from the explosion of poetry and creativity that characterised his early career. His pronounced use of Biblical imagery and phrases, mixed with various forms of archaic language, grounds the songs in the language of morality. He is clearly fascinated by the wonderfully expressive tone of the translation, much of it derived from William Tyndale’s 1525 version. The ‘King James version’ is, along with the works of Shakespeare, the most influential text in the history of English literature. Its tone and its prose rhythms can be found to have parallels in very many texts of English literature over the last four centuries, including explicitly religious texts like The Pilgrim’s Progress as well as works by agnostics like Thomas Hardy, whose novels often contain implied criticism of the bigotry and hypocrisy of the church. On this remarkable album, Dylan combines this unique amalgam of language with his usual influences of folk and blues material and his own colloquial interjections. He creates densely poetic and highly ambiguous songs that not only summarise where his own ‘head was at’ in 1967 but also reflect rather soberly on personal morality during an era in which hedonistic excess was being promoted by most rock musicians. The songs appear to be a deliberate attempt to ‘stand back’ from the psychedelic craziness that his earlier songs had done much to encourage. But this does not imply that Dylan had experienced any kind of religious ‘conversion’ – that, of course, was to come much later. However, he now engages seriously for the first time with the themes of redemption and salvation which will feature strongly in his future work. Calm and quiet as the songs are, they indicate that he is setting himself on a path of religious and spiritual exploration which will loom large for the rest of his career.

Leave a Reply