DYLAN’S GOSPEL YEARS

(an amended version of this blog appears in ‘Minstrel Boy: The Metamorphoses of Bob Dylan’

The Gospel Years: November 1st 1979. The Warfield Theater in San Francisco looks unimpressive from the sidewalk, resembling just a regular cinema in a busy street. Built in the 1920s, up till now it has been mainly showing movies. It was, however, originally built to house vaudeville performances. The slightly gaudy neo-classical interior design is reminiscent of grandiose silent movie epics like D. W. Griffiths’ Intolerance. The theatre holds just over 2,000 so it is small enough for the audience to catch the nuances of stage performances. Rather than playing a larger venue such as Winterland, Bob Dylan has been booked into a fourteen night residency here (over a mere sixteen days). It seems that he wants to communicate his new message personally to audiences in as intimate a setting as possible. Tonight an extraordinary drama is about to begin to unfold.

The three backing singers Regina Havis, Mona Lisa Young and Helena Springs take the stage. Regina Havis begins a monologue about a penniless old woman who is thrown off a train for having no money to pay the fare but who then, with Jesus’ help, miraculously causes the train to stop. The conductor, acknowledging her holiness, then allows her to board the train again. This morphs into I’ve Got My Ticket, Lord, a gospel standard from the 1940s, as the three singers demonstrate their considerable vocal range and power. The audience are deathly quiet at first. But then the singers perform another gospel song, then another. Then another… The audience are clearly getting a little twitchy now. To some extent they have been prepared for this, having heard about Bob’s conversion. Many of them have digested the songs on the Slow Train Coming album, which has been out for a couple of months. But perhaps they are now wondering whether Bob will appear at all…

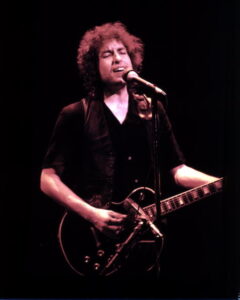

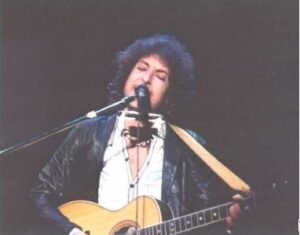

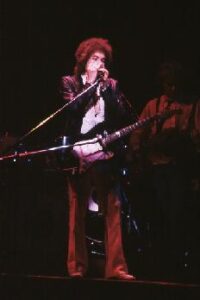

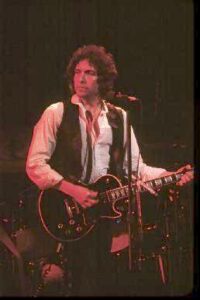

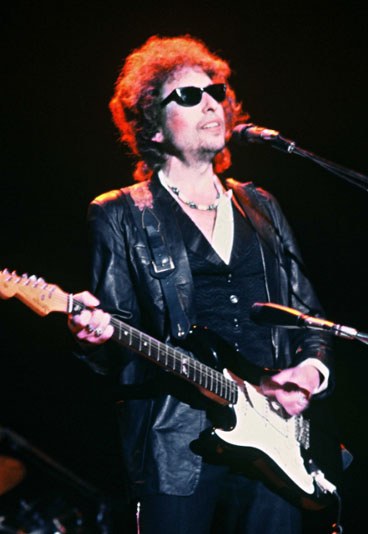

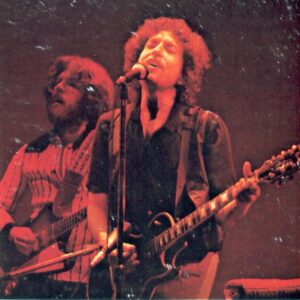

When Dylan finally takes the stage, he leads a crack band of session musicians, including Spooner Oldham on keyboards and Jim Keltner on drums, into the insistent chugging rhythm of Gotta Serve Somebody. The seventeen song set is drawn entirely from the recent album, along with nine new unrecorded religious songs. The three black women singers now play a key role, supplying gospel-style call and response vocals. Although Dylan is – not surprisingly on this first gig of the tour – slightly tentative at times, it is already possible to discern a new passion and ferocity in his performances, whether playing the angry prophet of Slow Train, the humble believer in I Believe in You or the ‘sacred lover’ of Precious Angel. The show ends with him interchanging vocals with the singers in the ‘gospel sing-a-longs’ Blessed is the Name and Pressin’ On. The audience joins in enthusiastically with the church-style handclaps.

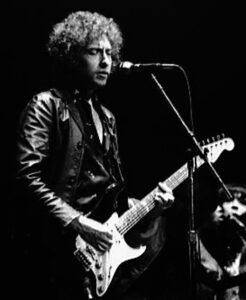

The crowd, although perhaps a little shocked and mesmerised, is generally respectful on this occasion. Unlike 1966, there is no booing. The real confrontations with audiences are still to come. But there is little doubt that, just as when he had shocked audiences by ‘going electric’ some thirteen years earlier, Dylan is enjoying this confrontational drama. Tonight he says little to them by way of explanation but there is no doubt that he means business. Whereas on the 1978 tour he had indulged in showy stage costumes, he is now dressed in a plain tee shirt and jeans. He is a little unshaven and unkempt, and there is a clear sense of rebellion in those piercing blue eyes.

THE GOSPEL SHOWS

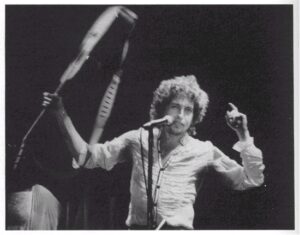

It would not always go so smoothly. The opening shows of the San Francisco residency in 1979 of fourteen shows over sixteen days attracted a number of enthusiastic Christian followers who were already engaged with Dylan’s message. But by the end of the residency, as rumblings in the crowd began to break out into heckling, mainly in the form of cries of …rock and roll!… Dylan began to feel the need to explain himself onstage. Before Slow Train on 16th November he delivered the following diatribe:

…Thank you. You know we read in the newspaper every day, what a horrible situation this world is in. Now God chooses the foolish things in this world to confound the wise. Anyway, we know this world is going to be destroyed, we know that. Christ will set up his kingdom in Jerusalem for a thousand years where the lion will lie down with the lamb. Have you heard that before? … Have you heard that before? … I’m just curious to know, how many believe that?…

Later on in the show, Dylan will announce that he has been delivered from Satan. In a later show in Santa Monica, he will tell the audience that he believes in a God who can raise the dead. As one heckler calls out for Like a Rolling Stone he ignores him, declaring that Satan is …the God of this world!… In an interview he will later claim that the initial impetus for his conversion began during a late 1978 show when a fan threw a silver cross onstage. He felt impelled to pick up the cross, which he was indeed seen wearing onstage during the final dates of that tour. Then he relates the story of his revelatory ‘vision of Jesus’ in a hotel room. Soon he will be delivering extended, if often rambling, ‘sermons’ on stage, along with his own rather colourful interpretations of Bible stories, mixed with some rather bizarre reflections on contemporary politics, especially regarding the current situation in which Iran’s Revolutionary Guards were holding US citizens hostage.

There is no doubt that Dylan was, at least at first, so committed to his new world view that he was desperate to both communicate and spread his new faith. By the time of the show in Tempe Arizona on 26th November, he faced continuous barracking from an especially hostile crowd. But instead of trying to pacify them by playing one of his classics, he responded with two extremely long and bitter rants, blaming the hostility of the audience on the Antichrist and declaring that …there are only two kinds of people, saved people and lost people… When someone in the audience cries out for …rock and roll!… his extraordinary response is … You can go see Kiss and you can rock-n-roll all your way down to the pit!…

Dylan’s embrace of gospel music was seen by some in a positive light as another one of his excursions into an authentic American musical form, just as in previous iterations he had embraced country music and the blues. Gospel has always been one of his major influences. In his early folkie days he had covered traditional spirituals such as Wade in the Water, Gospel Plow, Go Tell It on the Mountain, Jesus Met the Woman at the Well and Dink’s Song. Many of his most well loved songs like All Along the Watchtower and When the Ship Comes In had featured explicitly religious imagery and references. Blowin’ in the Wind had been adopted as one of the ‘marching songs’ of the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s and was sometimes sung in churches as if it was a hymn. In 1970 an entire album of Dylan’s songs was recorded by the gospel group Brothers and Sisters of Los Angeles.

The modern form of Gospel music emerged in the 1930s, under the influence of composers such as Thomas Dorsey (author of standards such as Peace in the Valley and Take My Hand, Precious Lord). Dorsey was a blues musician who had played frequently with Tampa Red and Ma Rainey. He did much to introduce a blues based sensibility into the music of black churches in the South. By combining the traditions of blues and spirituals, often expressed in rhythmic audience clapping and singing, Dorsey helped to popularise a form of music which – although it tended to stick to conventional Christian pieties in its lyrics – acted as an extremely effective safety valve for the frustration which black people felt in regard to their continuing oppression. Its influence on early rock and roll was profound. Artists like Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis and James Brown were all grounded in this music, with its extraordinary focus on powerful vocal expression. Soul music, which emerged in the late 1950s, combined elements of gospel and blues. Its main protagonists like Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, Dionne Warwick and Sam Cooke had all begun singing in church.

Dylan’s move into a ‘religious period’ was thus seen by some as a natural one. Many singers and performers over the years have ‘got religion’. Two of his great heroes Elvis Presley and Johnny Cash, both recorded whole albums of devotional music without any significant negative reaction from their fans. But his scornful reference to the music of glam rockers Kiss, who were extremely popular in the 1970s, illustrates the tension between the supposed spiritual purity of religious ideals and the earthy and often highly sexualised music of the blues and rock and roll. In religious circles many still argued that rock and roll was basically sinful. Both Lewis and Richard took time out to create religious works, partly out of guilt for having popularised ‘the devil’s music’. But while Dylan was scornfully referring in Gotta Serve Somebody to a …rock and roll addict, dancing on the stage/ Money and drugs at his command, women in a cage…he was at the same time producing some of the most direct rock of his career, with many of his new songs being built around strong rhythms and hard hitting riffs.

From his early twenties Dylan had had to cope with many of the difficult and restricting aspects of stardom. With his distinctive profile, he had become one of the most recognisable entertainers in the world and was constantly hounded by fans and the media; his opinions sought on every political and moral issue. He reacted against all this attention in a number of ways, avoiding most ‘showbiz’ events; never appearing on chat shows and restricting interviews. He tried to guard the details of his private life as much as possible; marrying in secret and, after the controversies of his ‘going electric’ period, withdrawing from regular touring and trying to live a relatively normal life in his countryside retreat in Woodstock. But such efforts only added to his mystique. Since he first became a public figure he had been held up as an ‘oracle’ whose every pronouncement and lyrical twist was analysed in depth (and often wildly misinterpreted). Eventually his rural ‘hideout’ became so well known that he had to retreat into the comparative anonymity of city life. When he finally reemerged onto the public stage his high profile tours of the 1970s made him a massive headlining act, capable of attracting huge crowds, such as the 200,000 who saw him at the Blackbushe concert in Surrey in 1978.

In the process of once again becoming a prominent public figure and a prolific performer, Dylan’s personal life had fragmented. His marriage collapsed and he became involved in long, bitter and costly divorce proceedings. While there was no doubt about the sincerity of his new beliefs, some commentators speculated that Dylan’s new devotion to Jesus was – at least in part – a defensive reaction to the way his fans, seeing him as a prophet or even a semi-divine figure, idolised him in a way that no other ‘pop star’ had ever experienced. By claiming to have discovered ‘higher truths’ than those he explored in his songs, he could then hopefully avoid the responsibility of his fans expecting him to always be the ‘one with the answers’.

Many of his fans were, however, dismayed by what appeared to be the obsessional nature of his new faith. They found Dylan’s insistence that it was the only true path hard to swallow. Such an attitude appeared to contradict his previous commitment to freedom of thought and rejection of conventional values. But what many fans found most disturbing was that, in the process of becoming ‘born again’ he appeared to have embraced the reactionary form of right wing nationalistic conservatism espoused by members of the Vineyard Fellowship, the hard line ‘born again’ group which attracted many ex-hippies and drug users, and to which he now subscribed. In early songs like A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall, Let Me Die in My Footsteps, Masters of War and With God on Our Side, he had excoriated the mentality that led to the nuclear standoff of the Cold War. But now he appeared to be embracing the coming of Armageddon in the form of nuclear war as the fulfillment of Biblical prophecy, claiming that only the elect of believers (naturally including himself) would survive in order to live sin-free lives under the benevolent dictatorship of a returned Jesus.

This new political stance appeared to be heavily influenced by the ‘prophesies’ contained in the bestselling book by Hal Lindsey, The Late Great Planet Earth. In this bizarre tome Lindsey argued that the apocalypse predicted in the Book of Revelation was now imminent, and would be triggered by a war in the Middle East. Dylan repeated many of Lindsey’s predictions in his on stage rants. These ideas were sometimes echoed in the equally rambling speeches of Ronald Reagan, who would be elected President in that same year. Dylan’s apparent embrace of such millennial right wing politics occurred at a time in which the threat of nuclear war seemed to loom especially large. It seemed to many of his fans that he had now become nothing less than a political reactionary.

Inspired by his ‘conversion experience’, Dylan entered an extremely prolific phase, writing all the songs that would appear on 1979’s Slow Train Coming and 1980’s Saved, along with a number of other compositions, in the months before the tour. Although he played virtually the whole album live, Saved would not be released until June 1980, by which time Dylan’s three ‘pure gospel’ tours had been completed. Despite the fact that both albums were recorded in Muscle Shoals studios in Alabama under the aegis of veteran producer Jerry Wexler (renowned for his highly intuitive and sympathetic work with leading soul artists such as Aretha Franklin, Otis Redding, Ray Charles, and Wilson Pickett), Slow Train Coming and Saved are very different in tone and style. Slow Train Coming is heavily ‘produced’ with an especially ‘smooth’ sound, dominated by the melodic guitar picking of Dire Straits’ lead singer and guitarist Mark Knopfler. With Straits drummer Pick Withers also on board, at times the album sounded like the tasteful soft rock that had recently made that group so popular. Saved, on the other hand, which features Dylan’s touring band, veers more towards the ‘live in the studio’ approach that Dylan generally took towards recording.

The two albums also have considerable differences in tone and subject matter. In Slow Train Coming Dylan seems concerned to communicate the reasons for his conversion. He includes tributes to the woman who had apparently led him towards his spiritual path, along with several songs that outline his own determination to pursue that path, despite the opprobrium of friends and contemporaries. In many ways, despite the smoothness of its sound, the album is an angry one which depicts the struggles of a person in transition between one set of beliefs and another. Saved, in contrast, presents a series of simpler, more devotional songs which incline more towards a traditional gospel sound and which mostly avoid making any political comment.

It is hardly surprising, given their subject matter, that the songs are very different to much of Dylan’s previous work. In some cases, however – although his political viewpoints seem to have shifted considerably – they do resemble his early ‘finger pointing’ material. However, by switching to a decidedly dogmatic ideological stance, his song writing had now been confined between particularly narrow parameters. The prevailing sense of ambiguity in his lyrics, which had been a crucial element of the poetic effect of so many of his songs, is largely missing. The use of adopted personas is now rarer. These songs clearly express personal convictions which are unarguably his own. Also a number of his new songs appeared to have been written in considerable haste, and rely on rather awkward or obvious rhymes. Perhaps most importantly, his characteristically use of ironic humour had also become very subdued.

Although the musical structures of these songs often created a powerful effect, as Dylan and his highly proficient new band poured great passion and belief into the material, he now appeared to have become a proselytiser first and a poet second. This created considerable difficulties for his fans. Despite his great acuity and range as a musician, his fame and appeal had always rested primarily on his lyric writing. He had been acclaimed as a poet ever since he delivered the Freewheelin’ album in 1963. Although he had publically rejected the role of ‘spokesman for his generation’ early in his career, he was still lauded by fellow musicians and music writers as the greatest lyricist of his era. He was also seen as the heir to the Beat Poets, with Allen Ginsberg in particular becoming a devotee. The influence on his work of the Romantic poets, T.S. Eliot, Shakespeare and indeed of much of the English Literary canon was undisputed. Listening to a Dylan record or seeing him in concert involved an immersion in the poetic mysteries of his songs. Now, having apparently sublimated his great lyrical gifts to the promulgation of a ‘message’ (and hardly an original one at that) it seemed that many fans would now have to try to appreciate his work purely on its musical merits. It seemed that the one factor that really defined his greatness had been submerged.

The most problematic tracks on Slow Train Coming are arguably the most musically potent. Slow Train and When You Gonna Wake Up are both direct, insistent rock songs with memorable refrains and dynamic musical structures. The central metaphor of Slow Train, which depicts the imminent but apparently inevitable arrival of the Biblical millennium, is couched in typical blues imagery. The idea of a ‘train to heaven’ had been powerfully expressed in the traditional This Train is Bound for Glory (adapted and popularised by Woody Guthrie) and Curtis Mayfield’s highly moving People Get Ready (which Dylan later performed on several occasions). But these ‘spiritual trains’ are taking their passengers directly to heaven. In contrast, Dylan’s ‘slow train’ is a force of violent destruction which will lay waste to the world in preparation for the prophecies in the Book of Revelation.

GOSPEL SONGS

The opening lines of Slow Train …Sometimes I feel so low down and disgusted/ Can’t help but wonder what’s happening to my companions… set the tone immediately. Dylan expresses that ‘disgust’ throughout a song which, in its own way, is as angry as The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll or Only a Pawn in their Game. But while the appeal of those old songs had rested on a presumption of basic human dignity and was presented through the voices of relatively humble narrators, the tone Dylan adopts here is decidedly patronising and didactic. He asks if his ‘companions’ have …counted the cost it’ll take to bring down/ All their earthly principles they’re gonna have to abandon... because the ‘slow train’ which is …coming up around the bend… will present them with no choice. It seems as if Dylan is now rejecting all the values in his songs which his ‘companions’ had previously accepted and is condemning them for not accepting his new stance. For many of them, such apparently narrow minded ‘preaching’ was hard to take.

Slow Train, the first of these songs to be written, contains some elements that could have appeared in his previous work. The Bootleg Series release Trouble No More includes a sound check version of the song from 1978 with completely secular lyrics, remnants of which appear in the recorded version. In two of the verses, Dylan steps sideways and tells us about a woman ‘down in Alabama’ who gives him some useful advice. Later we hear that she goes to Illinois with …some bad talking boy she could destroy…. Some of the lyrics also appear to be reminiscent of his early ‘finger pointing’ songs, as they present a powerful critique of rampant capitalism. We hear that …People starving and thirsting, grain elevators are bursting… before Dylan declares …Oh, you know it costs more to store the food than it do to give it… There are also some highly effective lines which condemn religious hypocrisy. …They talk about a life of brotherly love… he sings …Show me someone who knows how to live it… In perhaps the most resonant verse he condemns …Big-time negotiators, false healers and woman haters/ Masters of the bluff and masters of the proposition… He declares that …the enemy I see wears a cloak of decency/ All nonbelievers and men stealers talkin’ in the name of religion… and asserts, rather startlingly, that such hypocrites are …fools glorifying themselves/ Trying to manipulate Satan…

In the third verse, however, Dylan combines his new tone of rather judgemental social criticism with lines which stray into a kind of grotesque semi-racism, combined with the kind of flag waving xenophobia which was anathema to many of his fans: …Sheiks walking around like kings, wearing fancy jewels and nose rings/ Deciding on America’s future from Amsterdam to Paris… Elsewhere he employs the kind of ‘patriotic’ cliché beloved of American conservatives: … In the home of the brave/ Jefferson’s turning over in his grave… Slow Train is thus a weird amalgam of progressive social concern and reactionary prejudice. It is without doubt a very well structured and dramatic piece of music but it falls rather awkwardly between elements of Dylan’s characteristically sharp lyricism and his desire to extol the gospel. It is the kind of song that was well received in concert, with its dramatic and ominous undercurrents and powerful music often obscuring some of its more dubious sentiments. By 1981, while it still appeared regularly in the set lists, the verse referring to the ‘sheiks’ was being omitted.

When You Gonna Wake Up is also built around an infectious riff, although its much-repeated refrain… When you gonna wake up/And strengthen the things that remain… is an inherently conservative statement which it would have been impossible to conceive of earlier incarnations of Dylan delivering. The song again takes a scattergun approach to what he sees as the iniquities of the present day world. It contains a number of striking lines, including the opening …God don’t make promises that he don’t keep… and later the insidiously taunting …Do you ever wonder just what God requires/ Do you think he’s just an errand boy to satisfy your wandering desires?… But again the tone of the song is somewhat hectoring. We hear that innocent men are in jail, while ‘unrighteous doctors’ are apparently …dealing drugs that’ll never cure your ills… Dylan seems to be lecturing his listeners in a rather condescending way, dismissing both left and right wing political philosophies: …Karl Marx has got you by the throat/ Henry Kissinger has got you tied up in knots… His depiction of a corrupt world is withering, but lines such as: …You got men who can’t hide their peace and women who can’t control their tongues… and …Adulterers in churches and pornography in the schools… again display distinctly reactionary sentiments rooted in social attitudes that were alien to most of Dylan’s fans. When the song was performed on his 1984 tour it was given a completely new set of secular lyrics, with even the refrain being changed to ….When you gonna wake up/ Maybe you never will…

Gonna Change My Way of Thinking takes the form of a conversation that Dylan seems to be having with himself about how he intends to try to get rid of old attitudes in order to embrace his new world view. It is based around a standard blues riff, with the first two lines of each verse being repeated in time honoured fashion. Dylan throws in some decidedly clunky rhymes …Make myself a different set of rules… is rhymed with ….Stop being influenced by fools… Later …Doing your own thing and just being cool… is rhymed with …You forget about the golden rule… The final lines assert that …There’s a kingdom called Heaven/ A place where there is no pain of birth/ Well the Lord created it, mister/ About the same time He made the earth… Such lines are juxtaposed rather awkwardly with a few more authentically bluesy expressions such as …I got a God fearing woman, one I can easily afford/ She can do the Georgia crawl/ She can walk in the spirit of the Lord… It is perhaps not surprising that, when Dylan rerecorded the song for The Gospel Songs of Bob Dylan, a 2003 album mainly comprised of covers from this period by prominent gospel singers, he wrote a completely new set of lyrics, most of which are quite secular except for the sarcastic line: … Jesus is calling, He’s coming back to gather up his jewels/ We are living by the golden rule, whoever got the gold rules….

The album also contains two tracks which could be called ‘religious love songs’. The rather lightweight Do Right to Me Baby (Do Unto Others) is on one level a simple restatement of the Biblical ‘golden rule’. It is a pleasantly infectious track with a repetitively catchy and slightly jazzy tune in which Dylan implores a lover to treat him fairly. Despite its Biblical basis, it comes over as quite light hearted and is certainly not ‘preachy’. There is no mention of Jesus or the Bible here, although the title phrase is taken from Matthew 7:12’s account of the Sermon on the Mount. …All things, therefore, that you want men to do to you, you also must likewise do to them; this, in fact, is what the Law and the Prophets mean… The chorus is simple but effective: …If you do right to me baby/ I’ll do right to you/ You gotta do unto others/ Like you’d have them do unto you… Dylan tells us he …Don’t want to judge nobody, don’t wanna be judged/ Don’t want to touch nobody, don’t want to be touched… and then …Don’t want to hurt nobody, don’t want to be hurt/ Don’t want to treat nobody like they was dirt… In the same vein he asserts that he doesn’t want to shoot, buy or bury ‘nobody’. The rest of the song continues rather mechanically, with Dylan reasserting that he does not to burn cheat, defeat, confuse or amuse anyone.

The more ambiguous I Believe in You appears to be a rather desperate declaration of faith. It is closely based on Smoke Gets in Your Eyes (a musical standard from the 1930s (written by Jerome Kern and Otto Harbach) with its use of dramatic pauses after the first word of each verse. The first two verses refer to how ‘they’ …look at me and frown/ They like to drive me from this town… and later …They…show me to the door/ They say don’t come back no more… There is a melodic bridge section which counter poses the verses effectively. The lines …Oh….when the dawn is nearing/ Oh… when the night is disappearing/ Oh…when the night is disappearing/ Oh…this feeling Is still here in my heart… are particularly evocative, with the pause after the first line again reinforcing the narrator’s hesitancy. There is a certain level of humility which most of the religious songs lack. Dylan avoids hectoring and is not afraid to expose his own vulnerabilities. In early live performances with the full band, this quality can sometimes be buried, although Dylan played many more restrained versions during the Never Ending Tour. Perhaps the most moving reading of the song is by Sinead O’Connor, who originally recorded it for a Christmas compilation album in 1992. She invests the song with a tremulous and very believable sense of spiritual fragility.

One of Dylan’s few attempts at humour from this period is the ‘religious nursery rhyme’ Man Gave Names to All the Animals, which proceeds, over a light reggae beat, to explain how various animals were named. The repeated chorus of …Man gave names to all the animals/ In the beginning, long time ago… anchors the six verses, in which we hear of the origins of bears, cows, bulls, pigs and sheep. In the final verse the rhyme ‘lake’ is left hanging, but we know that it should obviously rhyme with ‘snake’. On first hearing this is quite amusing, if slightly ominous, although the joke does wear off rather quickly. Gotta Serve Somebody, which opens the album, is rather more successful in this vein. By any measure it is an odd choice to kick off an album of devotional songs. There is, however, a particularly strong chorus: …You gotta serve somebody/ It may be the devil or it may be the Lord/ But you gotta serve somebody… which at least leaves some room for listeners to make a choice. It has proved to be easily the most enduring song from this era and has been a staple of Dylan sets throughout the Never Ending Tour era, owing to its impressive dynamics as a rock song. A plethora of covers have appeared over the years, notable examples being versions by Willie Nelson, Bette Le Vette, Etta James and Aaron Neville. The tone of the song is generally light hearted, although the seven verses contain many ‘throwaway’ lines.

The song delivers a number of amusing contrasts: …You may be an ambassador to England or France/ You may like to gamble, you may like to dance/ You may be the heavyweight champion of the world/ You may be a socialite with a long string of pearls… A ‘shopping list’ of individuals follows, with a businessman , a ‘high degree thief’, a doctor, a chief, a state trooper, a ‘young Turk’, the head of a TV network, a ‘rock and roll addict’ and a construction worker all being presented with the choice Dylan has outlined. There are condemnations of corrupt figures, such as …a preacher with spiritual pride’…and …a city councilman taking bribes on the side…. Later he even refers to his given name of Zimmerman: …You may call me Terry, you may call me Timmy/ You may call me Bobby, you may call me Zimmy… Over the many years of its performance history, Dylan alters and adapts these lyrics in many ways. By the time of the Rough and Rowdy Ways tour of 2001-4, in which the song is regularly featured, its religious message has become considerably diluted. Despite its rather flippant tone, there is a suggestion that ‘serving the devil’ is actually a choice which the singer himself may be trying (not always successfully) to avoid making.

Precious Angel, which was released as a single, is perhaps the album’s most commercial track. It is distinguished by some especially memorable guitar playing by Mark Knopfler and has a sweetly appealing chorus: …Shine your light, shine your light on me… (repeated three times) …You know I just couldn’t make it by myself/ I’m a little too blind to see… The song is addressed to the ‘angel’ who introduced Dylan to his new faith. …How was I to know you’d be the one?… he tells her …To show me I was gone/ How weak was the foundation I was standing upon… But there is little real humility here. The infectious melody suggests loving affection but Dylan’s assertion that …You either got faith or you got unbelief and there ain’t no neutral ground… is troublingly dogmatic. The third verse is especially vindictive, as Dylan castigates his ‘so called friends’: …Can they imagine the darkness that will fall from on high/ When men will beg God to kill them and they won’t be able to die…

Dylan outlines a vision he had experienced, of a woman ‘drawing water for her husband’: …You were telling him about Buddha, you were telling him about Mohammed in the same breath/ You never mentioned one time the man who came and died a criminal’s death… He is of course referring to Jesus, although despite the direct address, the identity of this woman is unclear. It can hardly be the ‘precious angel’ herself. In the next verse he addresses the ‘angel’ directly, with the rather haunting …We are covered in blood, girl, you know both our forefathers were slaves/ Let’s hope they’ve found mercy in their bone-filled graves… This makes it clear that the ‘angel’ is a black woman and that Dylan is making one of his extremely rare references to his Jewish heritage. After describing her as ‘the queen of my flesh’ and ‘the lamp of my soul’ we are told that …there’s violence in the eyes girl, so let us not be enticed/ On the way out of Egypt, through Ethiopia, to the judgement hall of Christ… Despite its pleasantly melodic surface, Dylan’s tone seems to evoke a harsh Old Testament morality rather than a more compassionate New Testament ethos. The reference to …spiritual warfare, flesh and blood breaking down…may be an echo of Corinthians 10:3 which states that …For though we walk in the flesh, we do not war after the flesh”… Wherever ‘Jesus meek and mild’ is, we will not find him here.

The closing track When He Returns, a song about the Second Coming, is conveyed with great passion over stark solo piano played by Muscle Shoals Studios veteran Barry Beckett. It also features some strongly suggestive imagery, much which is Biblically inspired. The song begins with the stirring statement …The iron hand, it ain’t no match for the iron rod… Jesus has often been personified as an ‘iron rod’. Revelation 2:27 includes the prophecy that, after the coming apocalypse…He shall rule them with a rod of iron; as the vessels of a potter shall they be broken to shivers… After denying a role as a prophet for so many years, Dylan now takes up this mantle, as he sings …The strongest wall will crumble and fall to a mighty God… The song is an eloquent expression of his apparently complete and literal acceptance of Biblical prophecies – harsh though they may be. When he sings …For all those who have eyes and all those who have ears/ It is only He who can reduce me to tears…. his sincerity and humility are obviously genuine. After this the lines …like a thief in the night he will replace wrong with right/ When He returns… are a little anticlimactic. The reference to a ‘thief in the night’ is commonly employed in payers and gospel songs. It is drawn from Thessalonians 1:5 where it is stated that …the day of the Lord so cometh as a thief in the night… Here Dylan sounds genuinely distraught, as if he is actually wrestling with the implications of what he now believes in. The abstract, and possibly vengeful, notion of ‘replacing wrong with right’ sits uneasily with the violent tone of the imagery.

At times Dylan, having accepted the terrifying implications of the prophecies of Revelation, appears to be trembling with fear as he struggles with his own faith. The beautifully judged series of images: …Truth is an arrow and the gate is narrow that it passes through… recall the lines in 1964’s Restless Farewell: …When the arrow is straight and its point is slick/ It can pierce through dust no matter how thick… As the song progresses the narrator begins to question himself: …How long can I listen to the lies of prejudice?… he asks …How long can I stay drunk on fear out in the wilderness?…. Now he seems to be imagining himself as Jesus, going through his forty days and nights in the desert as he tussles with his own relationship to God. In the third and final verse he tries to rid himself of his doubts: …Surrender your crown… he tells himself …on this blood-stained ground… perhaps acknowledging that he himself, who has been acclaimed by many as prophet and saviour, must give up such pretentions. When he delivers the anguished lines …How long can you falsify and deny what is real?/ How long can you hate yourself for the weakness you conceal?… he sounds like he is in genuine pain as he questions whether his faith is really strong enough for him to ‘surrender’ so many of his deeply held beliefs. Finally he delivers what could be seen as a reassuring coda: …Of every earthly plan that is known to man he is unconcerned/ He’s got plans of his own to set up his throne/ When He returns… When He Returns is a highly moving song because here Dylan seems to be questioning himself, unsure as to whether his faith is really strong enough to accept the full implications of Christian belief. This creates considerable dramatic tension and concludes an album which is certainly no ‘happy-clappy’ set of gospel sing-alongs.

Ain’t No Man Righteous, Ye Shall Be Changed and Trouble in Mind were written around the same time, although none made it onto the album. Ain’t No Man is an upbeat number which was performed on several occasions on the gospel tours with prominent support from the backup singers. With a title phrase taken from Romans 3:10, its lyrics are sometimes rather jarring: …Some like to worship the moon, others are worshipping the sun… and …You can’t get to glory by the raising and lowering of no flag/ Put your goodness next to God’s and it comes out like a filthy rag… The song is a fairly straightforward statement of the ‘we are all sinners’ variety which lays out its message quite explicitly, warning that …the devil likes to drive you from the neighbourhood… although in one couplet Dylan does hint at his own sinfulness, confessing that …Done so many evil things in the name of love, it’s a crying shame… and follows this with the neatly metaphorical …I never did see no fire that could put out a flame…. Ye Shall Be Changed, which appeared on the first Bootleg Series release, takes a particularly stern tone. The chorus repeats the title phrase before taking us back to Revelation: …In a twinkling of an eye, when the last trumpet blows/ The dead will arise… The song is addressed to a sinner who has …an emptiness that can’t be filled… It may be that Dylan, now hyper-conscious of his own failings, may be directing the song at himself.

Trouble in Mind – a slinky, ominous blues dominated by Barry Beckett’s deft piano runs – is a considerably darker piece. The narrator describes Satan, in an echo of Ephesians 2:2, as the …prince of the power of the air… He hears the devil whispering in his ear: ….Well, I don’t want to bore ya/ But when ya get tired of Miss So-and-so I got another woman for ya… We hear that Satan will …deaden your conscience ‘til you worship the work of your own hands…The chorus, which consists merely of …Trouble in mind, trouble in mind/ Lord take away this trouble in mind… is quite stirring. But when he attempts to address his own contemporary situation, he comes over as self pitying and patronising …So many of my brothers… he sings ….they still want to be the boss/ They can’t relate to the cross/ They self-inflict punishment on their own broken lives/ Put their faith in their possessions, in their jobs or their wives… Dylan seems rather powerless here. It is undoubtedly Satan who is the ‘star’ of the song. In the final verse, he complains that his life on earth consists merely of suffering and that …Satan will give you a little taste, then he’ll move in with rapid speed/ Lord, keep my blind side covered and see that I don’t bleed…. Although he pleads for God to take away his troubles, it seems that Satan is winning out here.

The tracks on Saved are mostly more straightforward attempts by Dylan to celebrate his faith. They are thus closer to traditional gospel material, with the power of the songs being carried by the vocal harmonies and the repetition of key phrases. At times the music approaches a state of transcendent frenzy. Here Dylan avoids the dubious political prognostications that mar songs like Slow Train and When You Gonna Wake Up, as well as his attempts to portray himself as a ‘voice crying in the wilderness’. The title track is driven by some nimble fast piano playing by Spooner Oldham and a solid contribution on bass by co-writer Tim Drummond. In the manner of many gospel songs, it seems to accelerate as it moves towards its climax. It begins with a compelling intro: …I was blinded by the devil/ Born already ruined/Stone-cold dead/ As I stepped out of the womb… The song is a kind of prayer, as Dylan proclaims …By his grace I have been lifted/ By his word I have been healed/ By his hand I’ve been delivered/ By his spirit I’ve been healed… and later…By his truth I can be upright/ By his strength I do endure … Dylan and the backing vocalists fervently proclaim their salvation, repeating …I’m so glad!… and …I want to thank you, Lord!… as the music rises to a rousing climax.

Pressing On is another piano-based devotional piece with fairly minimal lyrics which again begins at a slow pace, with Dylan exchanging vocals with his backup singers, before working up into a righteous frenzy. As the song builds and builds in intensity the singers supply powerful gospel harmonies. In performance the interplay between Dylan and his backing vocalists conveys a truly authentic gospel style. There is no attempt here to criticise non-believers or make ill judged political pronouncements. The song has only two verses and mostly consists of variations on the chorus line of …I’m pressing on to the higher calling of my Lord… Dylan begins by explaining that he is often asked by others to …Prove to me that He is Lord, show me a sign… He retorts with …What kind of sign do they need when it all comes from within?/ When what’s lost has been found, what’s to come has already been… From there on, he on mostly lets the music do the talking.

Solid Rock is equally unpretentious and is built around a fierce and infectious repeated riff. It is also focused on a strong and distinctive chorus: …Well, I’m hangin’ on to a solid rock/ Made before the foundation of the world… followed by the invocatory …I won’t let go and I can’t let go/ And I can’t let go, won’t let go, no more…. This is repeated three times, and is interspersed by two short verses outlining that Jesus (who is not actually named here) was …chastised… hated… and ….rejected by a world that He created… Dylan testifies that …He never gave up ‘til the battle’s lost or won… The tension that the song creates is expressed most clearly by the contrast between ….It’s the ways of the flesh to war against the spirit… and the increasingly desperate chorus. The singer thus dramatically portrays the ‘spiritual warfare’ he is experiencing as he clings lovingly onto his ‘rock of ages’.

Covenant Woman (which is a kind of ‘follow up’ to Precious Angel) is another ‘spiritual love song’ which again pays tribute to the woman who assisted his conversion. The track has an appealing melody although its chorus, with lines like …I just gotta tell you I do intend/ To stay closer than any friend… sounds somewhat contrived. Dylan compares his love for the woman to the covenant that the Israelites make with God in Exodus. …I’ll always be right by your side… he tells her …I’ve got a covenant too… He describes her as …shining like a morning star… a term used to describe Jesus in Revelation 22:16, although this is followed by the rather patronising …I know I can trust you to stay where you are… He idealises her in the manner of conventional love songs, telling her that the Lord …must have loved me so much to send me someone as fine as you…

What Can I Do For You? is a direct address to Jesus, claiming that he has …pulled me out of bondage and made me renewed inside… although the assertion that …You’ve chosen me to be among the few… smacks of religious elitism. There is the odd striking line such as …Who would deliver him from the death he’s bound to die?… but this is followed by the stumbling …Well, you’ve done it all and there’s no more anyone can pretend to do… In the final verse, which begins with the memorably imagistic …I know all about poison, I know all about fiery darts… Dylan admits that … I don’t deserve it but I sure did make it through… proclaiming …I don’t care how rough the road is, show me where it starts… The combination of self proclaimed humility and elitist spirituality is, however, rather unconvincing.

Saving Grace , which was revived around thirty times on the Never Ending Tour between 2003 and 2012, is a depiction of spiritual struggle in which Dylan asks his Lord for forgiveness, confessing that …I’ve escaped death so many times/ I know I’m only living/ By the saving grace that’s over me… He states that the Lord is his …sole protection… against …the devil’s blinding light… and asserts that …It gets discouraging at times but I know I’ll make it… The song appears to suggest that he was at an extremely low ebb before his conversion and that his new faith has saved his life as well as his soul. He begs forgiveness for his sins and asserts …I’ll put all my confidence in him… Although it ends with conventional pieties: …The wicked know no peace and you just can’t fake it/ There’s only one road and it leads to Calvary… it communicates its message effectively. Dylan even has the self awareness to assert that …It gets discouraging at times…

Are You Ready? , the closing song on the album, delivers a series of simple messages. Much of its effect depends on the interaction between Dylan and the backing vocalists. Asking listeners …Have you decided whether you want to be/ In heaven or in hell?… this is another warning of the coming of Armageddon. Dylan references Isiah 27:1, inquiring whether the listener is ready for …that terrible swift sword… (a phrase that is also used in the famous civil war song Battle Hymn of the Republic). In the chorus he asks both the listener and himself whether they are ready for the upcoming Day of Judgement. At times he sounds rather uncertain about whether he himself will be saved. Whereas in What Can I Do For You? he had claimed to be among the elect, here he asks himself whether he is ready to …lay down my life for the brethren… wondering if he can…surrender to the will of God… or whether he is …still acting like the boss…

In the Garden is perhaps the album’s most resonant song. Its dramatic structure made it a live favourite and it was played around two hundred times on Dylan’s tours from 1986 onwards. Here he delivers a convincingly dramatic series of questions. Following a well worn gospel template, the first and last two lines of each verse repeat them, beginning with …When they came for him in the garden did they know?… followed by …When he spoke to them in the city did they hear?… …When he healed the blind and crippled did they see?… …Did they speak out against them did they dare?… and …When he rose from the dead did they believe?… Most of the intervening lines also consist of questions. There are references to Nicodemus, one of Jesus’ prominent followers, as well as the healing of Lazarus: … Pick up your bed and walk … The song conveys a quietly vengeful tone throughout. Its melodramatic stop-start structure creates considerable tension, with full throated support from the backing singers, while churchy organ and piano intertwine with some prominent bass runs from Tim Drummond. Although Dylan can certainly be said to be delivering a very conventional Christian message, the use of the questions does at least leave the listener with some space to potentially supply their own answers. Interestingly, the assumed answer to all of the questions is ‘no’.

In many ways the most impressive performance on the album is the opening track; a cover of the country standard A Satisfied Mind, written by Joe ‘Red Hayes’ and Jack Rhodes and originally a hit for Porter Waggoner. This is performed over minimal instrumentation and features some highly skilful vocal interaction between Dylan and the singers. The song is not overtly ‘religious’ although it recounts its message that money is not as important as spiritual satisfaction with considerable eloquence. In his stage shows of 1979-80 Dylan included a number of covers, mainly of gospel songs, such as the rather stirring Rise Again, a song by contemporary Christian song writer Dallas Holm, I Will Sing, I Will Sing; another gospel sing-along by Max Dyer and Abraham, Martin and John (written by Dick Holler); which decries the assassination of martyred leaders Lincoln, King and Kennedy and which had been a hit for Marvin Gaye.

Leave a Reply