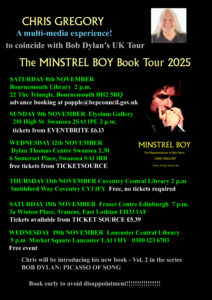

The MINSTREL BOY Book Tour 2025

Hi folks here’s the dates for my forthcoming Book Tour. I will be introducing MINSTREL BOY

and the PICASSO OF SONG trilogy and performing excerpts from the book. Hope you can come!

The tour has been arranged to co-incide with Dylan’s upcoming UK tour and many of the venues are

those in which he is playing the same evening.

1) SATURDAY 8th NOVEMBER Bournemouth Library 2 p.m.

22 The Triangle, Bournemouth BH2 5RQ Contact popple@bcpcouncil.gov.uk

Advance booking required but free to attend max capacity 50- they will set up booking form

2) SUNDAY 9th NOVEMBER Elysium Gallery Swansea 2 p.m.

Contact Scott Mackay bar@elysiumgallery.com 07932077898

210 High St Swansea SA1 1PE

tickets from EVENTBRITE £6.13

3) WEDNESDAY 12th NOVEMBER Dylan Thomas Centre Swansea 2.30

6 Somerset Place, Swansea SA1 1RR 01792 463980 capacity about 30.

free tickets from TICKETSOURCE

4) THURSDAY 13th NOVEMBER Coventry Central Library 2 p.m

Smithford Way Coventry CV1 1FY free event

5) SATURDAY 15th NOVEMBER Fraser Centre Edinburgh

info@thefrasercentre.com

£5 tickets available online at TICKETSOURCE

6) WEDNESDAY 19th NOVEMBER Lancaster Central Library 5 p.m

Market Square Lancaster LA1 1 HY free event

REVIEW OF: CHRIS GREGORY, MINSTREL BOY: THE METAMORPHOSES OF BOB DYLAN

https://rollason.wordpress.com/2025/09/08/review-of-chris-gregory-minstrel-boy-the-metamorphoses-of-bob-dylan/

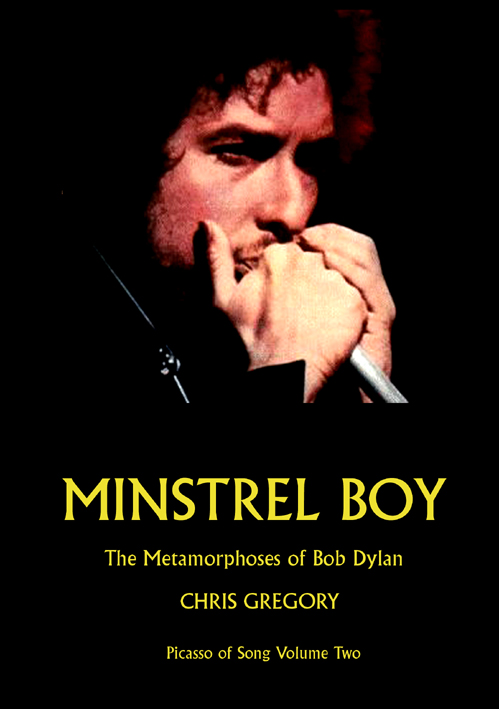

CHRIS GREGORY, MINSTREL BOY: THE METAMORPHOSES OF BOB DYLAN,

London: Plotted Plain Press, 2025, 450 pp. ISBN 978-0-955-7512-6-4

This substantial tome is the second volume of Picasso of Song, a projected trilogy by the author whose first volume, Determined to Stand: the Reinvention of Bob Dylan, won acclaim when it came out in 2021. The sequence of the three parts is reverse chronological: Determined to Stand covers ‘the 1990s to the 2022s’, while this second volume takes as its time range ‘1967 to the early 1990s’. Named after an obscure Dylan song first aired on Self Portrait in 1970, Minstrel Boy places under the microscope the following faces or phases of the artist’s career: withdrawal to the country (The Basement Tapes, John Wesley Harding, Nashville Skyline, Self Portrait, New Morning, Planet Waves); the return to fame and fortune (Blood on the Tracks, Desire, Street Legal); the adoption of born-again Christianity (Slow Train Coming, Saved, Shot of Love); and the post-evangelical phase including Infidels, Oh Mercy and more, up to Under the Red Sky. Interspersed with album and song analysis are bouts of first-hand reportage of key live performances or other events. As with the first volume, Gregory analyses for the period covered every song from every studio album, plus a significant number of additional tracks. There is a significant methodological variation from the first volume, as the song analyses are here ordered by album rather than by theme.

The volume begins with an introduction chronicling the celebrated Isle of Wight concert of 1969, the event which reaffirmed Dylan’s presence on the world stage following his lengthy absence in the wake of the motorcycle accident of 1966: already, the detailed song-by-song treatment offers a foretaste of what the book has in store. There are no footnotes, but the end matter includes an index (lacking in the first volume), a detailed bibliography of works by and about Dylan, a webography and an exhaustive discography.

It is taken as axiomatic that Bob Dylan is both popular entertainer and poet, and the two facets are privileged in turn in, respectively, the concert reviews and song text analyses. The facet of poet is underlined by the quote from Charles Baudelaire ‘s ‘The albatross’ that serves as epigraph to the book. Further epigraphs to chapters quote Edgar Allan Poe (‘The Poetic Principle’, 167), Rimbaud (the famous ‘I is another’ letter, 327) and Baudelaire again (‘Correspondences’), 253. Poe reappears in an evocation of ‘Man in the Long Black Coat’ (384) and in an interview on poetic inspiration cited on the last page (422). For Gregory ‘Dylan’s “song poetry” is multidimensional’(270) and he amply deserves to be up there with those famous names –not only the French symbolists, but also William Blake or a prose writer like John Bunyan., not to mention the King James Bible (93). Nor is intertextuality limited to literature – Gregory also evokes painters such as John Constable (118, for ‘New Morning’) René Magritte (404, for ‘Series of Dreams’), Angelica Kauffmann (246, for ‘Sara’ ), or indeed Pablo Picasso himself. (176,for ‘Tangled Up in Blue’.) .

On an important methodological point, Gregory avoids the automatic conflation of Bob Dylan with his songs -, and above all with his narrators. He accepts biographical readings when approaching a song like ‘Day of the Locusts’ or ‘Sara’, or, notably, much of the born-again material. However, for the bulk of the songs he treats their ‘I’ as a construct of the song, to be taken as a fictional subject who is not identical with the historical Bob Dylan. That fictional subject is generally denominated by Gregory as ‘the narrator’ – a term that works better than the alternative adopted elsewhere but scarcely used here, of ‘the singer”. Regarding the key aspect of text, it is obvious from the words on the page that Gregory’s default text is what Dylan sings on the studio album, and where there is a discrepancy between that sung text and the print version in Lyrics (what Gregory himself calls ‘Dylan’s edits in the official lyric books’ – 47). he almost always takes the former. Where there are multiple and competing textual variants (e.g. ‘When I Paint my Masterpiece’, ‘Tangled up in Blue’, ‘Caribbean Wind’), these are noted, at least selectively, and taken into account when reading the song. Occasionally (‘Down Along the Cove’, ‘To Be Alone With You’) a performance rewrite is treated as virtually a new song. Text is a complex issue in Dylan studies, and while Gregory’s strategy seems correct, it would have been useful to include an explicatory Note on the Text in the front matter.

The song analyses which lie at the core of this book are inevitably variable in their interest: some are brilliant, others appear a shade forced, and others again read as more like a paraphrase than an interpretation. Among the more arresting readings, we may note ‘Black Diamond Bay’ as a comic Hollywood pastiche, ‘Changing of the Guards’ as a commentary on the Tarot, or ‘Man in the Long Black Coat’ as a ‘dance with death’(385). Also noteworthy are interpretative flashes such as the notion that ‘I Dreamed I Saw Saint Augustine’ culminates in a fusion of the saint and Joe Hill, or, for ‘Idiot Wind’, the connection made between the song’s ‘boxcar door’ and Woody Guthrie; or again, for ‘One More Cup of Coffee’ the notion that the narrator feels about to be murdered by his hosts. There are fine analytic formulations, such as ‘Jokerman’ as a ‘self-reflexive moral fable’ (330) or ‘Every Grain of Sand’ as ‘a perfectly poised and balanced piece’ (331). The religious albums are sensitively dealt with: rather than seeing them as a homogeneous bloc, the author traces a spiritual journey in which Dylan at first follows the evangelicals and then gradually dissociates himself from them while remaining faithful to his God. Gregory thus sees the post-evangelical Dylan of a song like ‘Ring Them Bells’ as having attained ‘a Blakeian perspective in which conventional religious institutions are seen as instruments of evil and social oppression, blinding people to the power of true spirituality’ (399). In another register, Gregory’s analyses also show how Dylan’s long story-telling songs such as ‘Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts’ or ‘Brownsville Girl’ subvert linear sequence and challenge narrative convention.

The concert narratives range from the 1968 tribute to Woody Guthrie to the Concert for Bangladesh and the Band’s Last Waltz: there is even a flashback to the all-night queue for the 1978 Earls Court gig (261). The book concludes with an extract from a 1991 interview. The bibliography and discography, if not perfect, are impressively completist. All in all, Chris Gregory’s latest opus is to be welcomed as a valuable contribution to Dylan studies, and I for one will be eagerly awaiting the third and final volume!

Leave a Reply