A HARD RAIN’S A-GONNA FALL: THE ROAR OF A WAVE

…What immortal hand or eye

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry…

William Blake, The Tyger (1794)

…I read the news today, oh boy…

The Beatles, A Day in the Life (1967)

HARD RAIN

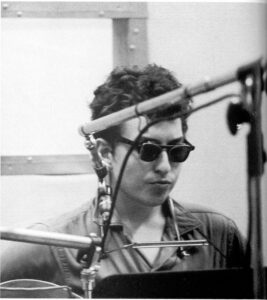

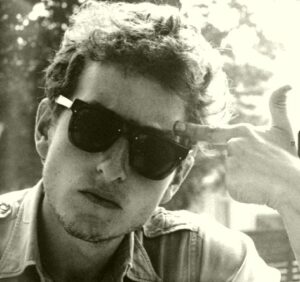

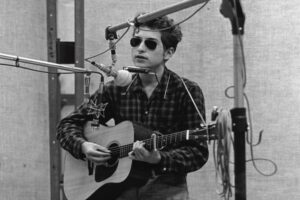

With the monumental and revelatory A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall Bob Dylan becomes so much more than just a folk singer. In this astonishing seven minute creation, he demonstrates that – as well as having immersed himself in the folk and blues traditions – he has also absorbed much of the English and European literary canon, especially Symbolist, Romantic and Beat poetry, as well as surrealist art. By combining all these influences, he creates a new form of ‘song poetry’ which uses music and dramatic recitation to create an intense emotional response in the listener. Hard Rain is a landmark in modern culture, demonstrating with great eloquence that popular songs can attain the status of high art. It also sets out a marker for Dylan’s career as the most articulate presenter of the pressing concerns of young people in the epochal decade that follows.

Dylan was barely twenty one years old when he wrote the song but he demonstrates an astonishing level of maturity in his approach. Rather than adopting the more literal tone of songs like Masters of War and With God on Our Side, he presents the apocalyptic scenario by means of an exhaustive string of highly visual, often symbolic, images. As Wordsworth, Coleridge and Blake had done, he fashions a unique poetic construction on the foundation of a folk ballad. At the same time he summons up the energy of Beat Poetry through his Whitmanesque use of listings and mesmeric repetition. He delivers the song with great passion, commitment and undeniable sincerity, as if he is squeezing every last drop of meaning he can from every word. The repeated and insistent rhythm of the song is expressed in a guitar figure that sounds more like a blues than a folk backing. The refrain is, once heard, unforgettable. It is not yet a rock and roll song but you can tap your feet to it.

HARD RAIN

Hard Rain is a highly cathartic song, which is born out of genuine despair and desperation. In the sleeve notes to the Freewheelin’ album Dylan states that it was written at the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis and that every line is potentially the beginning of a new song, as he thought he would not live long enough to write any more. Here, as in many of his other pronouncements, Dylan is certainly using ‘poetic license’. The song was actually completed and performed some weeks before the crisis unfolded, although the threat of nuclear war was already very much present in the months leading up to the standoff between the US and the USSR.

KRUSCHEV AND KENNEDY

In writing it he was confronted with a situation which was far beyond that faced by most of his poetic predecessors. Such was the awesome power of the H Bomb that the nuclear exchange which could have occurred in 1962 would indeed have destroyed human civilisation, if not the entire human race. The only precedents for such a scenario were ancient texts such as the Book of Revelation, which were concerned with nothing less than ‘the end of the world’. Thus Dylan assumed what might be described as a ‘prophetic’ tone, mixed with ineffable sadness and barely restrained anger.

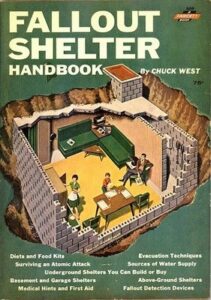

Dylan had grown up in an immediate post war world in which the Cold War had been a dominant, often obsessive, concern. In interviews in No Direction Home, Martin Scorsese’s 2005 film documenting his early years, he expresses his extreme bemusement about being forced to practice ‘nuclear drills’ at school. As part of the preparation for the possibility of a nuclear holocaust, fallout shelters had been built all over the country. In his early unreleased song Let Me Die in My Footsteps, Dylan delivers a powerful protest against their construction. The song begins with the unequivocal statement …I will not go down under the ground…

FAMILY IN A FALLOUT SHELTER

Each verse ends with …Let me die in my footsteps/ Before I go down under the ground… There are a number of strong declarations in which Dylan pours out his disgust and scorn at those who build the shelters, which in reality would only provide temporary relief for the inhabitants if the worst were to happen: ..Some people thinkin’ that the end is close by… he sneers …’Stead of learnin’ to live, they are learnin’ to die…

He declares defiantly that …I will not carry myself down to die/ When I get to my grave, my head will be high… The sentiments in much of the song, however, are rather clichéd, with Dylan declaring: …There’s always been people that have to cause fear/ They’ve been talking about war now for many long years/ I’ve read all their statements and I’ve not said a word/ But now Lawd God, let my poor voice be heard… Later he tells us that if he were a rich man …I’d throw all the guns and the tanks in the sea/ For they all are mistakes of our past history…

In the concluding verses, however, the song becomes more authentically poetic as Dylan celebrates the American landscape, very much in the manner of Woody Guthrie’s anthem This Land is Your Land… He cries: … Let me drink from the waters where the mountain streams flood/ Let the smell of wildflowers flow free through my blood… He then instructs the listener to …Go out in your country where the land meets the sun/ See the craters and the canyons where the waterfalls run/ Nevada, New Mexico, Arizona, Idaho/ Let every state in this union seep down deep in your soul…

HARD RAIN

The song was performed several times by Dylan in 1962 and was almost included on Freewheelin’ before being replaced by Masters of War. It remains one of his most effective early protest songs, despite its mixture of strong imagery and lyrical doggerel. Most of the folk singers in Greenwich Village would have promoted it as a major composition. It is certainly more substantial than Dylan’s off the cuff Cuban Missile Crisis, recorded for Broadside magazine, in which he recalls … the fearful night we thought the world would end… and sings …The Russian ships were sailin’ all out across the sea/ We all feared by daybreak it would be World War Number Three… Unsurprisingly, this song does not even appear in any of the official lyric books.

Although Hard Rain was composed just a few months later, it represents a quantum leap in Dylan’s song writing. It makes no specific reference to war, nuclear or otherwise. By focusing on symbolic images, he creates a song whose sentiments can also be applied to the devastation of any human created catastrophe, whether it be war, ethnic cleansing or the destruction of natural environments. While Let Me Die in My Footsteps is relevant to a particular time and place, Hard Rain stands as a universal statement. As the years have gone by it has only become more relevant. The scenarios it describes could equally be applied to Vietnam, Afghanistan, Yugoslavia, Iraq, Palestine or the many conflicts in Africa that have unfolded in subsequent years. Much of the effectiveness of the song lies in its highly personal nature as all of its imagery is passed onto us through one individual’s innocent eyes.

Dylan took the melody and a few other elements of the song from the traditional ballad Lord Randall which he probably heard from American folk singer Jean Ritchie. The ballad consists of a dialogue between a mother and her son. She begins with the question …Oh where have you been, Lord Randall my son?/ Oh where have you been, my handsome young one?…. Over the next three verses she inquires as to where he had dinner, what he ate and how his bloodhounds are. He reveals that, after exploring the ‘wild wood’, he was fed by his lover. By the end of the song, however, it appears that the girl has poisoned him and that he is about to die.

JEAN RICHIE

Dylan uses this call and response structure in Hard Rain, changing ‘Lord Randall’ to ‘my blue eyed son’ and ‘handsome young one’ to ‘darling young one’. It is unclear in Dylan’s song whether the speaker is his mother or his father. Dylan himself has blue eyes, so it might be inferred that he is the young man who responds to the parental enquiries. In the five verses he is asked …Where have you been?…, …What have you seen?…, …What did you hear?…, …Who did you meet?… and finally …What’ll you do now?… In each verse the son gives his own impressionistic answers to each question. The contrast between the affectionate rhymes at the start of the verses and the bleak images that follow gives the song much of its iconoclastic power.

Each verse ends with…It’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard/ It’s a hard rain’s a-gonna fall… The simplicity of the refrain allows the powerful imagery of the verses to stand alone. One very unusual feature of the song is that, apart from the initial questions at the beginning of each verse, Dylan does not use conventional rhyming. This makes the declarations more authentic and revelatory. Dylan sometimes compensates for the lack of rhyme with pararhyme, with particular emphasis on similar line endings like ‘drippin’’, ‘bleedin’’, ‘warnin’’ and ‘blazin’. There is also much repetition, with five or six lines in each verse beginning with the same word and a liberal scattering of alliteration. In order to build up the tension, Dylan varies the line lengths of the verses. Verse one has nine lines, verses two and three have eleven, verse four has ten and verse five has sixteen.

In the first verse the ‘blue eyed son’’s response to the question …Where have you been… takes the form of five repetitive statements. The first: …I’ve stumbled on the side of twelve misty mountains… is relatively benign. But the descriptions of nature in what follows outline what has happened to the planet. He tells us: …I’ve walked and I’ve crawled on six crooked highways/ I’ve stepped in the middle of seven sad forests/ I’ve been out in front of a dozen dead oceans/ I’ve been ten thousand miles in the mouth of a graveyard… He begins by stumbling, walking and crawling. As he gains confidence in relating his ‘travels’, his journeys become more fantastical.

Now the highways, forests and oceans are personified. They take on human qualities of being ‘crooked’, ‘sad’ and ‘dead’. We can already tell that his account is a visionary one, which is confirmed by the final line, with the humanised image of the ‘mouth of a graveyard’ clearly indicating that the whole earth is now full of the dead. Dylan never spells the actual details of the destruction out literally, allowing us to channel our own visualisations and interpretations.

The short opening verse is, however, merely a prelude to the visual horrors that will follow. We are now presented with an image of extreme menace …I saw a new born baby with wild wolves all around it… We are not told what will happen next, but of course we can imagine it. The narrative now becomes increasingly imagistic, symbolic and apparently random … I saw a highway of diamonds with nobody on it…. presents us with an image of futility, as these shining diamonds are now worthless as nobody exists to value them. The son then tells us he sees…a black branch with blood that kept drippin’…

Again we are left to imagine where the blood on the dead, blackened tree has come from. This is followed by the surreal image of …a room full of men with their hammers a-bleedin’… which resembles a scene from a Salvador Dali painting. We are beyond reality now, entering a horrific dream land. We are then shown the image of a …white ladder all covered with water… This presents an image of purity – the opposite of the black branch from which blood is dripping – in the midst of all this destruction. But this is an illusion. The water, the product of the ‘hard rain’, is of course poisoned.

We then hear another surreal alliterative description of …ten thousand talkers whose tongues were all broken… Now the son imagines all the political and religious leaders, philosophical thinkers, warmongers, pacifists, protestors and weapons manufacturers gathered together in one room – ‘talkers’ who can no longer talk – as anything they might say would be, in these circumstances, entirely pointless. This is a spellbinding image of futility, but its dream like quality is immediately brought down to earth by the brutally contrasting …I saw guns and sharp swords in the hands of young children… the ultimate image, perhaps, of the perversion of innocence – one which has tragically been a feature of a number of real wars over the years, recalling the child ‘soldiers’ Hitler sent out to defend Berlin even though defeat was by then inevitable. Dylan’s shift from symbolism to the harshest of realism suddenly raises the emotional level of the song before the refrain comes in.

When we switch from visual to auditory images, it as if the son has been blinded and is now stumbling through the ruins. Or perhaps he is closing his eyes, tormented by his visions. He hears …the sound of a thunder… that … roared out a warnin’…and then …the roar of a wave that could drown the whole world… highly portentous reverberations that make the song’s global dimension quite clear. In another surreal line he hears ….one hundred drummers whose hands were a-blazin’… Drums are often associated with the coming of war. But this is a war like no other. Even the drummers’ hands are on fire. He then hears …ten thousand whisperin’ and nobody listenin’… which is set against …I heard one person starve, I heard many people laughin’… Having moved from the general to the specific, we are then presented with two more individual tragedies. He hears …the song of a poet who died in the gutter… a line which may be a foreshadowing of his own death and …the sound of a clown who cried in the alley… an image which follows on from the hollow laughter of the ‘many people laughin’’.

In giving us his list of people he met on his journeys, we are presented with another formidable list of images which raise the song to the level of hallucinatory intensity. It is as if the camera in this nightmarish movie has now zoomed in on a collection of random individuals. The deadpan delivery of …I met a young child beside a dead pony/ I met a white man who walked a black dog… gives us two striking visual images. Again the child is associated with the threat of extreme violence. This is followed by perhaps the song’s most compelling comparison. Firstly we are given the horrifically graphic …I met a young woman whose body was burning… followed by one of the few hopeful images: …I met a young girl, she gave me a rainbow…

In Genesis the rainbow appears after the Jehovah-driven worldwide cataclysm of The Flood. But there is no deity in this song. The image of hope comes from the song’s third and most powerful mention of a child, now offering love and hope rather than ‘guns and sharp swords’. Thus bitter experience and naïve innocence are juxtaposed with almost unbearable pathos. The verse ends with another comparison – more abstract this time but equally cutting. Firstly the son tells us …I met one man who was wounded in love… a common expression in sentimental songs which is countered darkly with the acidic …I met another man who was wounded in hatred…

The final extended verse replicates the sentiments of the last two verses of Let Me Die in My Footsteps, with the narrator, having been asked what his next move will be, defiantly expressing his wish to venture ‘out into the country’ where he may meet his death ‘honestly’. But now Dylan injects a slight ray of hope, as if he is holding onto the rainbow which the child has presented to him. The opening …I’m a-goin’ back out ‘fore the rain starts a-fallin’…. reveals that the cataclysm has actually not happened yet.

Therefore what has been shown to us in the previous verses is revealed not as an actual travelogue but as a series of revelatory visions or warnings. It seems that, if we could only imitate the narrator’s defiance then perhaps there is some hope of averting the disaster. He declares …I’ll walk to the depths of the deepest dark forests… evoking Blakes’s ‘forests of the night’ from The Tyger, thus entering a symbolic landscape in which, in another of the song’s most moving and revealing lines …the people are many and their hands are all empty…

In this final verse Dylan confronts the real present day situation, with the world on the absolute brink of disaster. We hear that …the pellets of poison are flooding their waters… This poison comes from the ‘hard rain’ which is as much a rain of lies and propaganda as a physically poisoning downpour. There are so many of these pellets that they have created the wave that threatens to ‘drown the whole world’ …The home in the valley meets the damp, dirty prison… suggests that the whole world has become a prison in which we are trapped, a place in which …the executioner’s face is always well hidden/ Where hunger is ugly, where souls are forgotten/ Where black is the color, where none is the number….

This is the state of a world which is about to be consumed by the coming holocaust. But then Dylan adds four extra lines of supreme defiance. He is still determined not to ‘go down under the ground’ and will broadcast this last-gasp message of hope to the entire world, even if it means that he will ultimately drown under the pressure of the endless ‘hard rain’ …I’ll tell it and think it and speak it and breathe it… he declares …And reflect from the mountain so all souls can see it…

These lines recall those in the famous spiritual Go Tell it on the Mountain, with the son now assuming the role of an Old Testament style prophet. There are echoes here of the Biblical Flood, from which only the mountain tops provided refuge. This is contrasted with …I’ll stand on the ocean until I start sinkin’… Unlike Jesus, the son cannot walk on water but at least he will try to do so, defying death until he is overcome. But despite these Biblical echoes, the universe of Hard Rain is a godless one. Only if the listeners can hear the voice of this lone – and entirely human – ‘voice in the wilderness’ can humanity be saved. Thus Dylan makes a plea for us all to reach into the depths of our humanity to prevent the song’s terrifying visions becoming real.

The son then takes a final deep breath, refusing to drown in despair and declares …But I’ll know my song well before I start singin’… Hard Rain is a song which any singer will have to work very hard to memorise, as Patti Smith found to her cost at the 2016 Nobel Prize Ceremony (at which she represented the absent Dylan) with her highly moving rendition of the song, accompanied by an orchestra. Halfway through her performance, overwhelmed by the occasion, she forgets the lyrics and has to ask the musicians to start again. Yet even such a mistake cannot diminish the awesome power of the song. It is almost as if she is trembling before the towering strength of the lyrics.

PATTI FLUFFS HER LINES!

Hard Rain has, not surprisingly, been a staple of Dylan’s live shows. He has performed it several hundred times in a variety of musical settings and arrangements. For a song which began as an adaptation of a folk ballad it has, perhaps surprisingly, been proved to work equally well as an up tempo rock number. The original version on Freewheelin’ is, however, very difficult to emulate. Laid down in a single take, it is an astonishingly realised and almost faultless rendition. Dylan’s one tiny stumble over the words at the beginning of the fourth verse, where his emotions almost get the better of him, only adds to its effectiveness.

Its strong rhythmic core was showcased rather dramatically in the audacious cover version by Bryan Ferry from 1973 (a hit single in the UK) which, although it omits one of the verses, establishes that it can be presented effectively as a highly danceable rock number. Ferry’s vocal presence, which is always close to camp, adds an ironic dimension. The sight of him miming to a song about the end of the world on Top of the Pops in front of dancing teenage girls was certainly a bizarre one. To his credit, however, Ferry does not trivialise the song but updates it into a historical era in which the nuclear threat had become normalised. His sardonic rock treatment worked as a strong reminder that the threat had not disappeared.

Hard Rain has proved to be surprisingly adaptable to a number of different treatments. On the Rolling Thunder tour in 1975, Dylan updates the song as a raucous rock number, with the Guam band, containing several guitarists and Scarlet Rivera on violin, in full frenetic swing. The lyrics are delivered at great speed. Even though there is a short instrumental break between verses four and five, it lasts just over five minutes. On the 1978 tour it was played as an instrumental at the start of the shows. In succeeding years it has taken many forms, sometimes reverting to an acoustic setting. In 1994 at Nara, Japan, Dylan performed it with an orchestra.In the 2000s it was delivered over an odd syncopated beat. There have many other cover versions. Pete Seeger renders a gentle reading emphasising the song’s pathos. Joan Baez’s version illuminates the stark beauty of the lyrics. The Staple Singers present it as a gospel-flavoured call and response number, while Leon Russell delivers a restrained and respectful bluesy rendering.

DYLAN NARA JAPAN 1994

It is quite remarkable how the young Dylan moved from the sub-Guthrie folksiness of Let Me Die to the poetic mastery of Hard Rain in such a short time. However, the potential imminence of the ‘end of the world’ may well, as Dylan hinted in his ‘one line being the start of every song’ comment, pushed him towards this new sensibility. Indeed, the entire ‘youth revolution’ of the 1960s, which was manifested most eloquently in what now seems like a ‘golden age’ of rock music, can be said to have been a reaction against the nuclear standoff of 1962. It was as if an entire generation was being pushed towards the heights of creativity because they did not expect that they, and the rest of the human race, could survive the dangers of the Cold War in perpetuity.

The echoes of this fear of planetary extinction can be heard in such ‘60s rock classics as The End by The Doors, Sympathy for the Devil by the Rolling Stones and A Day in the Life by The Beatles. There was a common perception among the young that their leaders, who had pushed the world to the brink of extinction, were insane. Therefore all existing social institutions and practices were being challenged. A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall, along with Stanley Kubrick’s masterful black comedy Dr. Strangelove (Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb) can be said to be one of the key texts in creating this mind set.

DR. STRANGELOVE – SLIM PICKENS

Hard Rain is thus highly significant from both a historical and a cultural perspective. It marks the beginning of the youth revolution of the 1960s, while establishing a new form of public poetry. Perhaps no other song in Dylan’s catalogue has been so analysed, with myriad interpretations appearing of its highly visual cavalcade of images. Far more than just a ‘protest song’, it is a kind of modern Homeric epic whose subject is the dignity of humanity in the face of its own possible extinction.

Its descriptions of the horror, despair and surreal juxtapositions that war brings about resemble a series of vivid paintings; images that are so powerful that – once fully absorbed – they will stay in the listeners’ minds forever. Dylan’s compelling imagistic narrative, composed in a fever of anxiety, touches on the most horrifying aspects of the human condition without sentimentality or equivocation. By engaging in such a desperate act of composition he is able to lift his art, and the art of song writing itself, to a new level.

Leave a Reply